The aim of this study is to evaluate the internal validity of a clinical test for the early diagnosis of shoulder adhesive capsulitis, called the Distension Test in Passive External Rotation (DTPER).

Materials and methodsThe DTPER is performed with the patient standing up, the arm adducted, and the elbow bent at 90°. From this position, a smooth passive external rotation is started, the affected arm being supporting at the wrist with one hand of the examiner and the other maintaining the adducted elbow until the maximum painless point of the rotation is reached. From this point of maximum external rotation with the arm in adduction and with no pain, an abrupt distension movement is made, increasing the external rotation, causing pain in the shoulder if the test is positive. This term was performed on a group of patients with shoulder pain of many origins, in order to analyse the predictive values, sensitivity, specificity, and the likelihood ratio.

ResultsThe DTPER showed a sensitivity of 100% (95% CI: 91.8–100%) and a specificity of 90% (95% CI: 82.4–94.8%). The positive predictive value was 0.62 and a likelihood ratio of 10.22 (95% CI: 5.5–19.01). False positives were only found in patients with subscapular tendinopathies or glenohumeral arthrosis.

DiscussionThe DTPER has a high sensitivity for the diagnosis of adhesive capsulitis, and is excluded when it is practically negative. False positives can easily be identified if there is external rotation with no limits (subscapular tendinopathy) or with a simple shoulder X-ray (glenohumeral arthrosis).

El propósito de este estudio es evaluar la validez interna de una prueba clínica descrita para el diagnóstico precoz de la capsulitis adhesiva de hombro: el Test de Distensión en Rotación Externa Pasiva (TDREP).

Material y métodoEl TDREP se realiza con el paciente de pie, el brazo adducido y el codo flexionado a 90°. Desde esta posición, se inicia un movimiento suave de rotación externa pasiva, sosteniendo el brazo afectado con una mano del examinador en la muñeca y otra manteniendo el codo abducido hasta que se alcanza el punto máximo de rotación indolora. Desde este punto de máxima rotación externa con el brazo en aducción y sin dolor, se realiza un movimiento brusco de distensión, incrementando la rotación externa, causando dolor en el hombro si la prueba es positiva. Es test se realizó en un grupo de 155 pacientes con dolor de hombro de múltiples orígenes para analizar los valores predictivos, la sensibilidad, especificidad y razón de verosimilitud.

ResultadosEl TDREP mostró una sensibilidad de 100% (IC 95%, de 91,8 a 100%) y una especificidad del 90% (IC 95%, de 82,4 a 94,8%). El valour predictivo positivo fue de 0,62 y la razón de verosimilitud de 10,22 (IC 95%: 5,5 a 19,01). Los falsos positivos se encontraron solo en enfermos con tendinopatías del subescapular o con artrosis glenohumeral.

DiscusiónEl TDREP tiene una alta sensibilidad para diagnosticar CA y cuando es negativo prácticamente la excluye. Los falsos positivos se pueden identificar fácilmente si existe una rotación externa sin limitación (tendinopatía subescapular) o con una radiografía simple de hombro (artrosis glenohumeral).

Idiopathic adhesive capsulitis (IAC) is a frequent shoulder pathology. The literature reflects prevalence values around 2–5% among the general population and a cumulative incidence of 2.4 per 1000 population-year, with an increasing trend among young females.1,2

In general, IAC patients have a limited shoulder mobility and pain with no history of prior trauma. The diagnosis is mainly obtained through clinical examination, since none of the available imaging studies has been proven effective to distinguish IAC from other entities.3

Early diagnosis of IAC can be difficult and patients tend to visit the clinic belatedly, often with a prior diagnosis of rotator cuff pathology and numerous and costly imaging tests. Some patients have even undergone prior surgical procedures to treat subacromial pathology.4 Therefore, any clinical test which allowed general orthopaedic surgeons or primary care physicians to establish a diagnosis of IAC at an early stage of the disease would undoubtedly help many patients. In addition, it would reduce costs associated to radiographs and treatment in this group of patients.5,6

The objective of the current study is to describe and analyse the internal validity of a new clinical test, the Distension Test in Passive External Rotation (DTPER), for the diagnosis of shoulder adhesive capsulitis.

Materials and methodsThe study included 43 patients with a suspected diagnosis of IAC, who had been attended at the specific shoulder consultation between June 2006 and June 2009. Since there is no accepted diagnostic test to confirm the pathology, the gold standard for DTPER was established as a clear limitation of passive external rotation of the shoulder with the patient under general anaesthesia, prior to definitive treatment and in the absence of pathological findings in a simple radiograph.

Only those patients who were examined under anaesthesia prior to undergoing the definitive treatment were included in the study. In the 43 patients, the definitive treatment consisted in shoulder manipulation under anaesthesia (MUA), followed by physiotherapy.7–9

Patients with a clinical suspicion of IAC who were treated exclusively through oral medication, infiltrations or physiotherapy were excluded from the validation study, since there was no reference test for the diagnosis, an essential aspect in order to validate any clinical test.

All patients had been treated conservatively with no success prior to MUA. The mean interval between the start of shoulder pain and performance of DTPER was 9 months (range: 3–24 months). The mean age of the 28 females and 15 males was 54 years (range: 34–76 years). The mean follow-up time after the MUA treatment was 36 months (range: 27–72 months).

Only 16 of the 43 cases attended consultation with a generic diagnosis of shoulder pain. A total of 21 patients had been diagnosed and treated for subacromial syndrome, four for supraspinatus tendinitis and three for partial supraspinatus tears. All 43 patients had received physiotherapy, seven had been infiltrated with corticoids, and one patient had undergone arthroscopic acromioplasty. A total of seven patients suffered diabetes mellitus.

We conducted a radiographic study of all patients, which included a simple shoulder radiograph in two planes. A magnetic resonance imaging scan was obtained for all patients, which reported minor subacromial pathology in 29 cases and no significant findings in the remaining 14.

After evaluating the limitation for painless passive shoulder mobility, with patients standing, the DTPER was conducted by placing the arm in adduction with the elbow next to the body in 90° flexion and neutral pronosupination (Fig. 1). Arm adduction was maintained, while the examiner placed the palm of a hand on the elbow of the patient. The examiner then placed the other hand on the volar side of the wrist of the patient placed in neutral pronosupination and a slow and progressive external rotation was carried out until maximum painless external rotation was achieved, noting an elastic resistance to the progression. Once that position of maximal painless passive external rotation was reached, there was an attempt to increase external shoulder rotation through a sudden movement. When the test was positive, there was an intense pain which triggered voluntary resistance to continue the rotation. The DTPER was considered positive as long as it triggered intense pain, regardless of the degree of shoulder rigidity. Therefore, if there was a limitation to passive external rotation, but the DTPER did not trigger pain, it was considered negative; conversely, if external rotation was scarcely limited, but the patient referred pain upon a sudden movement in the last few degrees, the DTPER was considered positive.

Distension Test in Passive External Rotation (DTPER): the gradual and slow increase in passive external rotation does not cause any pain until the end of the movement range and there is a slight resistance to progression. A sudden external rotation movement at that point causes intense pain in the shoulder. The test is positive regardless of the existing degree of movement.

All patients underwent the DTPER test on the day of their first visit to our Unit and immediately after undergoing general anaesthesia. We also conducted the test routinely in all the follow-up visits in the clinic after MUA.

The DTPER was also performed with 92 patients who were evaluated at our consultation due to shoulder pain with no history of trauma. This group of patients included a wide range of diagnoses: full-width rotator cuff tear, calcifying tendinitis, acromioclavicular arthrosis, glenohumeral arthrosis, instability, and suprascapular neuropathy. The gold standard for the diagnosis of these entities consisted in radiographic or electrophysiological confirmation associated to the clinical characteristics of each specific pathology.

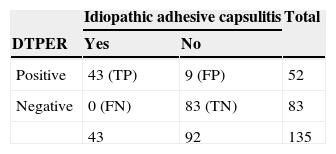

The validity criteria of DTPER were determined based on the sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, negative predictive value, likelihood ratio and overall accuracy of the test based on a 2×2 contingency table where the columns represented the presence or absence of IAC and the rows represented the positive or negative result of the test. Confidence intervals were calculated at 95%.5

Sensitivity is defined as the probability that a test is positive for a patient with the pathology. Sensitivity measures the capacity of the test to detect the pathology. Specificity is the probability that the test is negative for a healthy individual. The positive predictive value is the probability that a patient with positive DTPER corresponds to a subject with IAC. The negative predictive value is the proportion of patients with a negative DTPER who do not suffer IAC. The likelihood ratio indicates the value of the test to increase the certainty of a diagnosis. In the case of an isolated clinical test, a likelihood ratio over 10 is enough to establish that, if the test is positive, the patient suffers the pathology. Therefore, this test indicates the number of times that the probability of obtaining a positive result in a patient with the pathology increases by, compared to one who does not suffer it, thus representing an optimal indicator to confirm the diagnosis.

ResultsOut of the 135 patients who underwent DTPER, in 52 the result was positive: 43 with a confirmed diagnosis of adhesive capsulitis, five with subscapular tendon lesions and five with degenerative glenohumeral pathology (Table 1). In the rest of patients the result of the DTPER was negative. The test was positive in all patients with IAC.

2X2 contingency table of the Distension Test in Passive External Rotation (DTPER) and idiopathic adhesive capsulitis (IAC) of the shoulder.

| Idiopathic adhesive capsulitis | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| DTPER | Yes | No | |

| Positive | 43 (TP) | 9 (FP) | 52 |

| Negative | 0 (FN) | 83 (TN) | 83 |

| 43 | 92 | 135 | |

FN: false negatives; FP: false positives; TN: true negatives; VP: true positives.

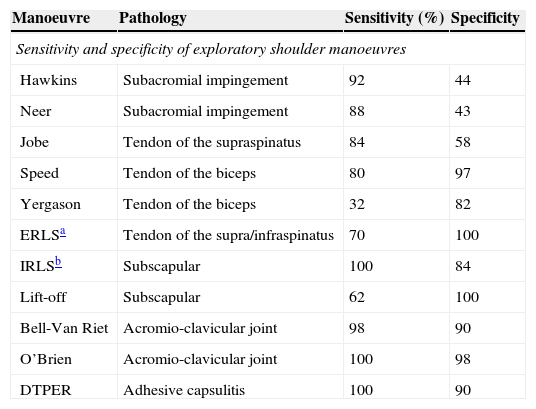

The DTPER showed a sensitivity of 100% (95% CI: 91.8–100%), a specificity of 90% (95% CI: 82.4–94.8%) and a proportion of false positives of 9.8% (95% IC: 5.2–17.6%). The proportion of false negatives was 0% (95% IC: 0.0–8.2%). The false positives were only found in patients with subscapular pathology or glenohumeral arthritis. These results compared favourably with those of other clinical diagnostic tests used commonly for the shoulder (Table 2).

Comparative sensitivity and specificity values of several diagnostic tests for shoulder pathology.

| Manoeuvre | Pathology | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity and specificity of exploratory shoulder manoeuvres | |||

| Hawkins | Subacromial impingement | 92 | 44 |

| Neer | Subacromial impingement | 88 | 43 |

| Jobe | Tendon of the supraspinatus | 84 | 58 |

| Speed | Tendon of the biceps | 80 | 97 |

| Yergason | Tendon of the biceps | 32 | 82 |

| ERLSa | Tendon of the supra/infraspinatus | 70 | 100 |

| IRLSb | Subscapular | 100 | 84 |

| Lift-off | Subscapular | 62 | 100 |

| Bell-Van Riet | Acromio-clavicular joint | 98 | 90 |

| O’Brien | Acromio-clavicular joint | 100 | 98 |

| DTPER | Adhesive capsulitis | 100 | 90 |

The predictive values were calculated based on an estimated prevalence of IAC of 14% calculated on the set of patients who attended our clinic due to shoulder pain without a traumatic origin over a period of 3 months. The positive predictive value of the DTPER test was 0.62 (range: 0.49–0.75), the negative predictive value was 1, meaning that a DTPER excludes the presence of IAC. The accuracy of the test for IAC was of 93.3% (95% CI: 87.8–96.5%), reflecting that DTPER has a very high probability of classifying a patient with IAC.

The likelihood ratio of this test was 10.22 (95% CI: 5.5–19). Therefore, the probability of obtaining a positive test in a patient with IAC is 10 times higher than in a patient without IAC.

A total of seven patients with IAC had a positive DTPER in the last monitoring visit after having been treated with MUA. All seven presented mild residual rigidity and a pain of variable intensity but only after activity. The patients reported being satisfied with the result of the MUA, as it had reduced pain, but the disease was not completely cured.

DiscussionIAC is a frequent cause of shoulder pain. The diagnosis in the initial phases can be difficult for general orthopaedic surgeons. The reason is that the associated signs and symptoms are not specific and there is no diagnostic imaging test that can confirm the presence of this pathology.3 Moreover, very often patients provide MRI reports which point to a minor pathology of the rotator cuff tendons, and which can lead the surgeon to believe that that is the cause of the pain. In fact, the majority of patients who attend a specialised shoulder consultation with IAC have been previously misdiagnosed with subacromial pathology and received treatment for it, some of them even undergoing surgical procedures, despite the fact that subacromial syndrome characteristically does not cause limitation of passive shoulder mobility. Therefore, improving the capacity to detect IAC in its initial phases would significantly reduce the number of unnecessary diagnostic tests and inadequate treatments.

The physiopathology of this disease involves an inflammatory process with an unknown origin, followed by fibroblastic proliferation which fundamentally affects the rotator interval and coracohumeral ligaments.10,11 When the arm is in adduction and the shoulder rotates externally, these structures are tensed. If the rotator interval is swollen, a sudden movement of maximal external rotation will cause pain due to the sudden stretching thereof.

At the same time that DTPER was being implemented in our clinical practice, Wolf et al.12 described a similar manoeuvre to diagnose IAC. However, in their test they describe that pain is caused throughout the entire range of mobility and passive external rotation. In practice, it is common for patients with IAC not to suffer pain in external rotation other than when the end of the movement range is reached. The basis of the DTPER technique is the sudden stretching of the anterior structures of the shoulder, which are always affected in IAC from the initial stages. In addition, it is the pain at the end of the movement that defines the test, regardless of the range of mobility of the shoulder.

Also based on the physiopathological principles of the disease, Carbone et al.13 reported a clinical test whereby pain was reproduced when the rotator interval was palpated immediately outside the edge of the coracoid. The test is positive when pressure causes pain, although there are some false negatives in obese patients. However, the validation process of any clinical test also requires having a reference test to diagnose the problem (gold standard) which can be used to confirm the test being validated.5 The previously described tests were not validated in relation to a reference test, since the diagnosis of IAC was only established based on the clinical exploration. Evidently, the situation in everyday practice is that the clinical examination cannot be very clear and the diagnosis of IAC is not obvious. We believe that confirmation of the limitation of the range of movement, particularly in external rotation, with the patient under general anaesthesia, along with the confirmation of a tear of the intraarticular adherences with manipulation under anaesthesia represent the reference test with which to confirm a diagnosis of IAC. Having corroborated our test with a reference test gives DTPER a more real value than other previously described tests.

Most published tests involving clinical examination of the shoulder, some of which are widely accepted for the differential diagnosis of shoulder pain, report, in the best of cases, lower sensitivity and specificity values than those obtained for IAC through DTPER, and in fact the majority of them present significant differences between sensitivity and specificity (Table 2).6

On the other hand, the likelihood ratio provides a strong diagnostic evidence when it reaches values between 5 and 10, and strongly points to the presence of the pathology being studied when the results are over 10, with the result obtained for DTPER being 10.22. Therefore, the probability that a positive test corresponds to a patient with IAC is over 10 times higher than for a subject without IAC. The overall accuracy of the test was 93%, a higher value than that obtained by other exploratory tests used for the shoulder, such as those reported by Hawkins (66%), Jobe (53%) and Gerber (64%).6

These aspects demonstrate the internal validity of DTPER, which can be considered as a simple method to identify patients suffering IAC. Based on our results, a negative DTPER result can practically exclude the presence of IAC. This is particularly important in the initial phases of the pathology: if a patient presents shoulder pain that cannot be clearly identified, together with good mobility – as is usually the case with patients suffering IAC in its initial stages – and the DTPER is negative, the physician may rule out IAC as the cause of the problem and focus on other possible diagnoses.14–16 On other hand, if the DTPER is positive under the same circumstances, the physician should entertain a high suspicion of a IAC in its initial stages. Only two diagnoses could be considered upon a positive test result: glenohumeral arthrosis, which is easily ruled out through a simple radiograph, and lesion of the subscapular muscle tendon, which should present normal, or even increased, external rotation and is associated with very characteristics findings in an MRI scan.

This study had several limitations. Firstly, there was no control group comparing the DTPER test with other clinical tests to detect IAC. This is due to the lack of comparable clinical tests which have been internally validated. Secondly, all DTPER were conducted by two surgeons experts in shoulder pathology, thus introducing a possible bias regarding less experienced orthopaedic surgeons. Lastly, the interobserver reliability has not been evaluated, since no observers who conducted the test in a different environment were included. This last point is necessary in order to demonstrate the external validity of a diagnostic tests and must necessarily be carried out at some point if the DTPER is to be useful in all environments. In any case, prior to an external validity study is it essential to verify the internal validity, as has been done.5

In conclusion, the DTPER has been proven to be a simple clinical test to perform, and to offer a high effectiveness for the early detection of patients with shoulder IAC. If the test is negative, the pathology can be ruled out. False positives were only observed in patients with glenohumeral arthrosis and pathologies of the subscapular tendon, both easily identifiable through imaging tests or an additional clinical examination.

Level of evidenceLevel of evidence II.

Ethical responsibilitiesProtection of people and animalsThe authors declare that this investigation did not require experiments on humans or animals.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their workplace on the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare having obtained written informed consent from patients and/or subjects referred to in the work. This document is held by the corresponding author.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Please cite this article as: Noboa E, López-Graña G, Barco R, Antuña S. Test de Distensión en Rotación Externa Pasiva (TDREP): validación de una nueva prueba clínica para el diagnóstico precoz de la capsulitis adhesiva de hombro. Rev Esp Cir Ortop Traumatol. 2015;59:354–359.