Deep gluteal syndrome (DGS) is characterised by compression, at extra-pelvic level, of the sciatic nerve within any structure of the deep gluteal space. The objective was to evaluate the clinical results in patients with DGS treated with an endoscopic technique.

MethodsRetrospective study of patients with DGS treated with an endoscopic technique between 2012 and 2016 with a minimum follow-up of 12 months. The patients were evaluated before the procedure and during the first year of follow-up with the WOMAC and VAIL scales.

ResultsForty-four operations on 41 patients (36 women and 5 men) were included with an average age of 48.4±14.5. The most common cause of nerve compression was fibrovascular bands. There were two cases of anatomic variant at the exit of the nerve; compression of the sciatic nerve was associated with the use of biopolymers in the gluteal region in an isolated case. The results showed an improvement of functionality and pain measured with the WOMAC scale with a mean of 63–26 points after the procedure (p<0.05). However, at the end of the follow-up, one patient continued to manifest residual pain of the posterior cutaneous femoral nerve. Four cases required revision at 6 months following the procedure due to compression of the scarred tissue surrounding the sciatic nerve.

ConclusionEndoscopic release of the sciatic nerve offers an alternative in the management of DGS by improving functionality and reducing pain levels in appropriately selected patients.

El síndrome de glúteo profundo (SGP) es una enfermedad caracterizada por la compresión a nivel extra-pélvico del nervio ciático (NC) por cualquier estructura en el espacio glúteo profundo. El objetivo de este estudio fue evaluar los resultados clínicos en pacientes con SGP manejados con técnica endoscópica.

MétodosEstudio retrospectivo de pacientes con SGP intervenidos con técnica endoscópica entre 2012 al 2016 con seguimiento mínimo de 12 meses. Los pacientes fueron evaluados antes de la intervención y durante el primer año de seguimiento con las escalas WOMAC y VAIL.

ResultadosSe incluyeron 44 cirugías en 41 pacientes (36 mujeres y 5 varones) con un promedio de edad de 48,4±14,5 años. La causa más frecuente de atrapamiento fueron las bandas fibrovasculares, hubo 2 casos de variante anatómica en la salida del nervio, y en un caso aislado, el atrapamiento del NC fue atribuido a la aplicación de biopolímeros en la región glútea. Se encontró mejoría de la funcionalidad y dolor valorado con la escala WOMAC con una mediana de 63 a 26 puntos después de la intervención (p<0,05). Al final del seguimiento un paciente continuaba con dolor residual del nervio cutáneo femoral posterior. Cuatro casos requirieron de revisión a los 6 meses posteriores al procedimiento, por atrapamiento de tejido de cicatrización alrededor del NC.

ConclusiónLa liberación endoscópica del NC es una alternativa en el manejo del SGP al mejorar la función y disminuir el grado de dolor, cuando existe una adecuada selección de pacientes.

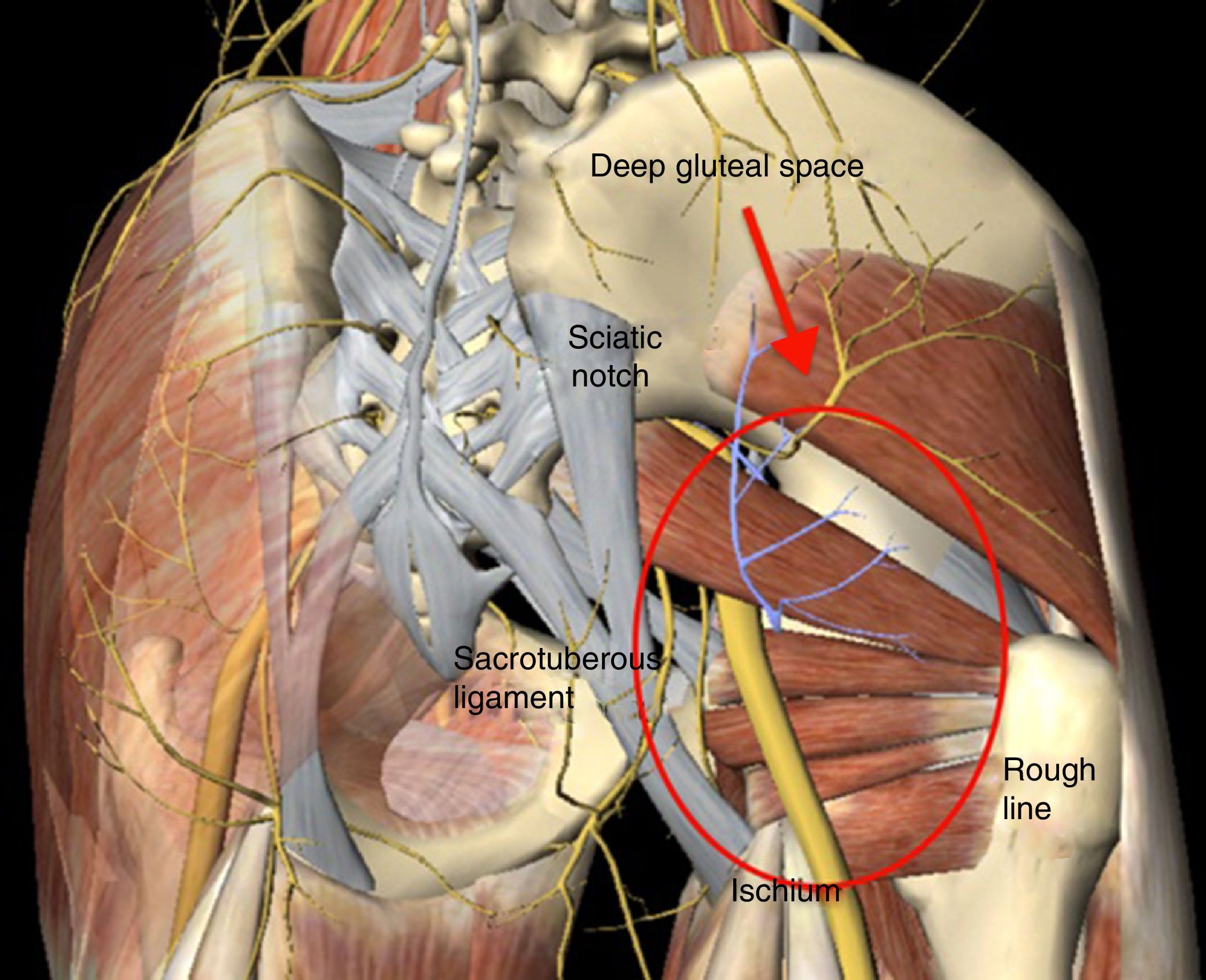

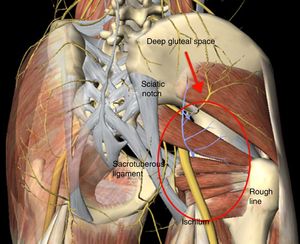

Deep gluteal syndrome (DGS) is characterised by compression, at extra pelvic level, of the sciatic nerve (SN) within any structure of the deep gluteal space (DGS).1 The DGS is defined in front by the femoral neck, from behind by the posterior edge of the gluteus muscles, on the side by the rough line of the femur and medially by the sacrotuberous ligament and the falciform fascia (Fig. 1). The predominating symptom is the inability to remain seated for prolonged periods of time, in addition to radiating pain down the affected leg. There are several aetiological factors for the development of DGS, including: direct trauma at gluteal or pelvic level, hypertrophy of the muscles in the deep region of the DGS, haematoma, and anatomical variants where the SN exits with respect to the pyroform muscles and fibrovascular bands.1–5

DGS continues to be difficult to diagnose in the treatment for the orthopaedic surgeon. This delays its identification, affecting the patient's quality of life. Diagnosis of DGS is made when there is clinical suspicion due to medical history and symptoms presented by the patient on physical examination in the absence of any lumbar condition.

Some manoeuvres exist which may help the physician to define diagnosis, including passive and active stretch tests of the piriformis muscle. These, together with infiltration of the DGS, highlight clinical suspicion.6

DGS treatment is initially conservative with physical therapy, which focuses on stretching all the tissues around the DGS, so as to move the anatomical structures at greatest risk of entrapment, such as the fibrovascular bands.7 This manoeuvre achieves a favourable outcome in over 87% of patients. However, a percentage of patients do not respond satisfactorily to this type of treatment.1

Surgery is considered for patients for whom the conservative approach has failed after a minimum period of 3 months, and both open surgery and endoscopic technique options have been described. The endoscopic approach lowers the risk of injury to the nearby structures by direct visualisation of the nerve, as well as reducing risk of infection and lesions, offering favourable outcomes with an improvement in patient pain level and functionability.1,8–12 The purpose of this study was to describe the clinical results in patients with DGS managed by endoscopy.

MethodsA retrospective study of patients diagnosed with DGS, treated with an endoscopic technique. The operations included took place between the years 2012 and 2016 with a minimum follow-up of 12 months. During the study period, 47 patients were operated on, and of these, 44 met with the selection criteria. Subjects under 18 and those with prior pelvis or hip operations were excluded. All procedures were performed by the same surgeon. This study was approved by the Research Institution Ethics Committee.

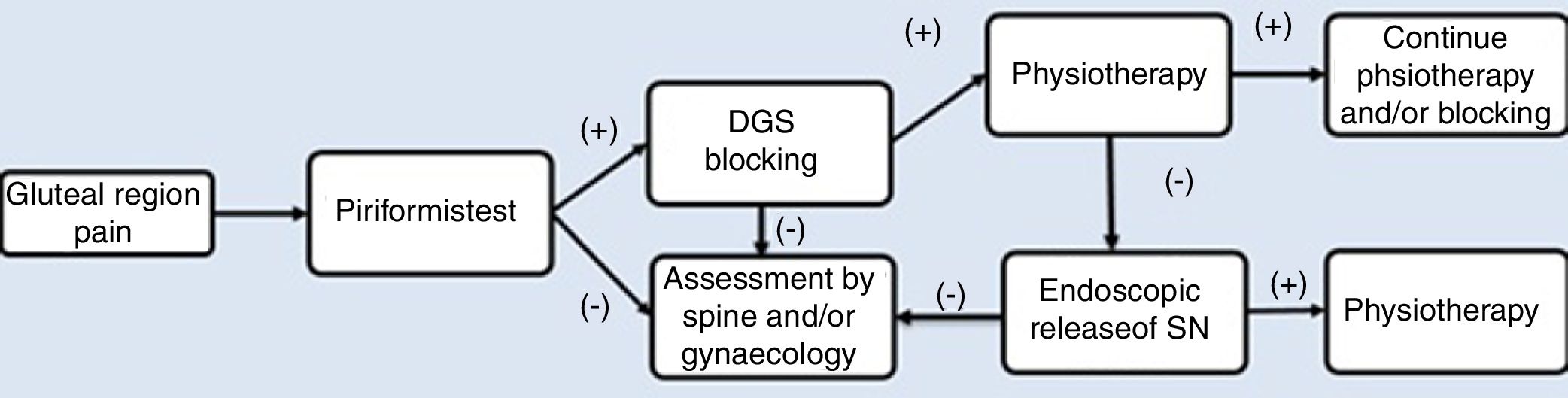

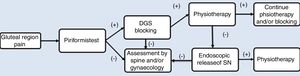

As part of the management protocol, a detailed medical history was made, describing the onset of symptoms, trauma background and previous operations. The diagnosis process is described in Fig. 2. Radiological studies included anterior–posterior projections (AP) of the pelvis, Dunn 45° and 90°, Lequesne false profile, as well as a magnetic resonance (MR). The MR of the lumbosacral spine was indicated in patients with a clinical suspicion of lumbar radiculopathy to rule out the origin of pain in the posterior region of the hip. MR of the pelvis was indicated to identify the pathway of the SN and rule out possible intrapelvic compressions after ruling out points of lumbar compression in cases with where there is a negative result in the diagnosis of SN blockage.

Pain in the gluteus region on palpation was present during physical examination and considered a symptom of diagnosis, which was later verified with specific DGS tests. The passive piriformis stretch test was performed, with the patient in a seated position with the knee extended. The practitioner passively moved the flexed hip into adduction with internal rotation while palpating 1cm lateral to the ischium (middle finger) and proximally at the sciatic notch (index finger).6 The active piriformis test was performed with the patient in lateral position with 40° of hip flexion and 40° of knee flexion when the patient externally rotated against resistance. These tests were considered positive if the pain increased with this movement. In patients with suspected DGS, the diagnostic test of SN blocking was made in the region of the greater sciatic notch, which then blocks the nerve. The sensation of an improvement in pain was considered a positive test and indicated that entrapment presented in that region.6,13

Prior to the endoscopic procedure, all patients underwent physical therapy for a 3–6-month period in keeping with the management protocol, with no improvement or worsening of the pain (Fig. 2).

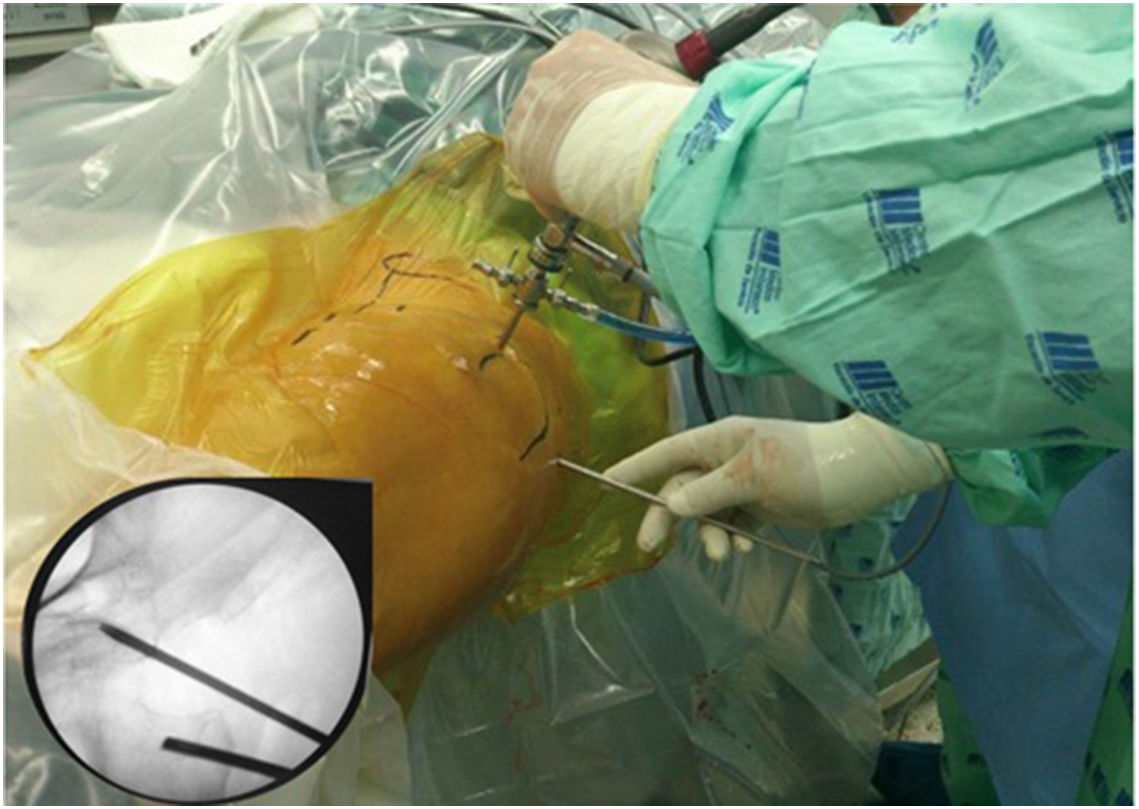

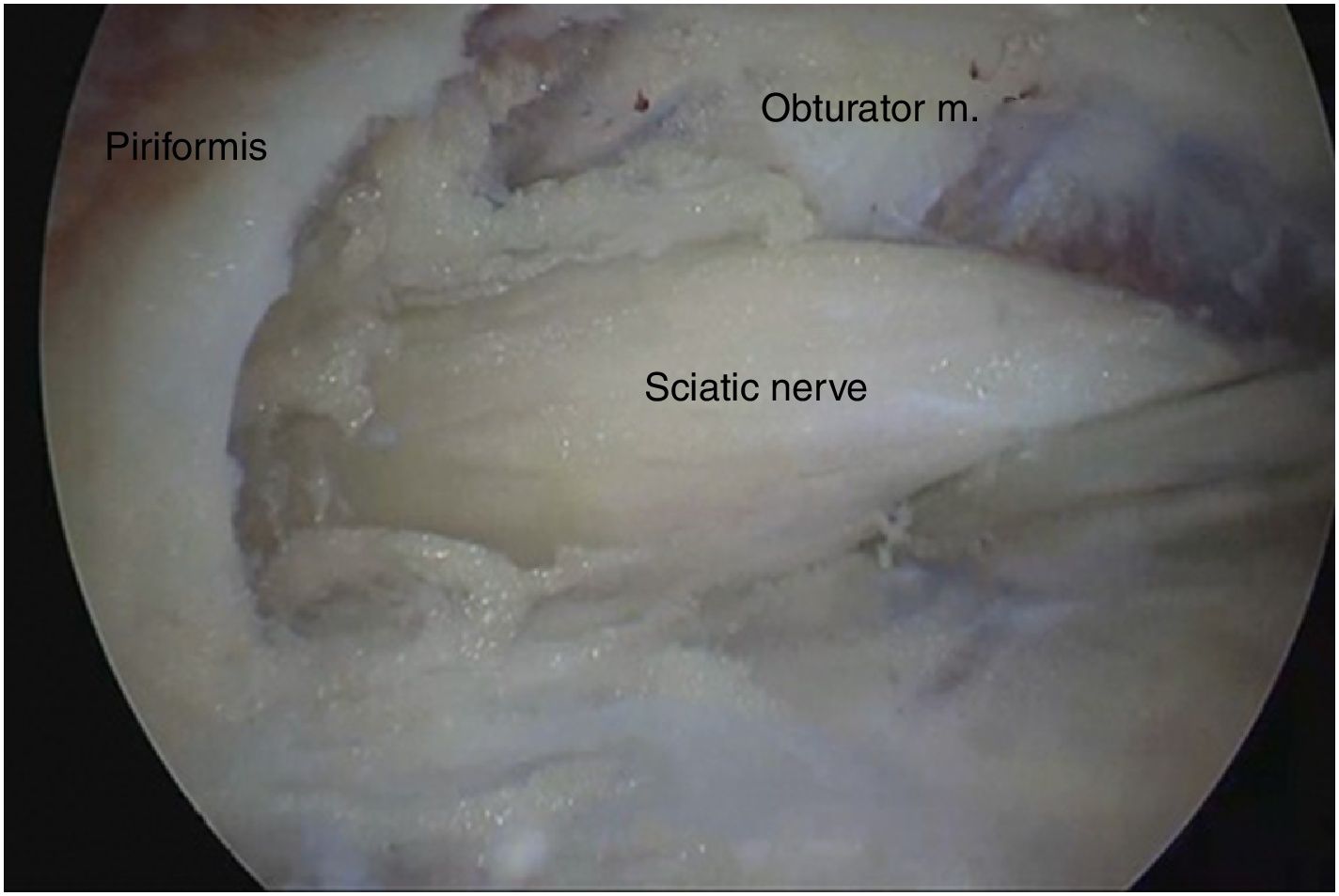

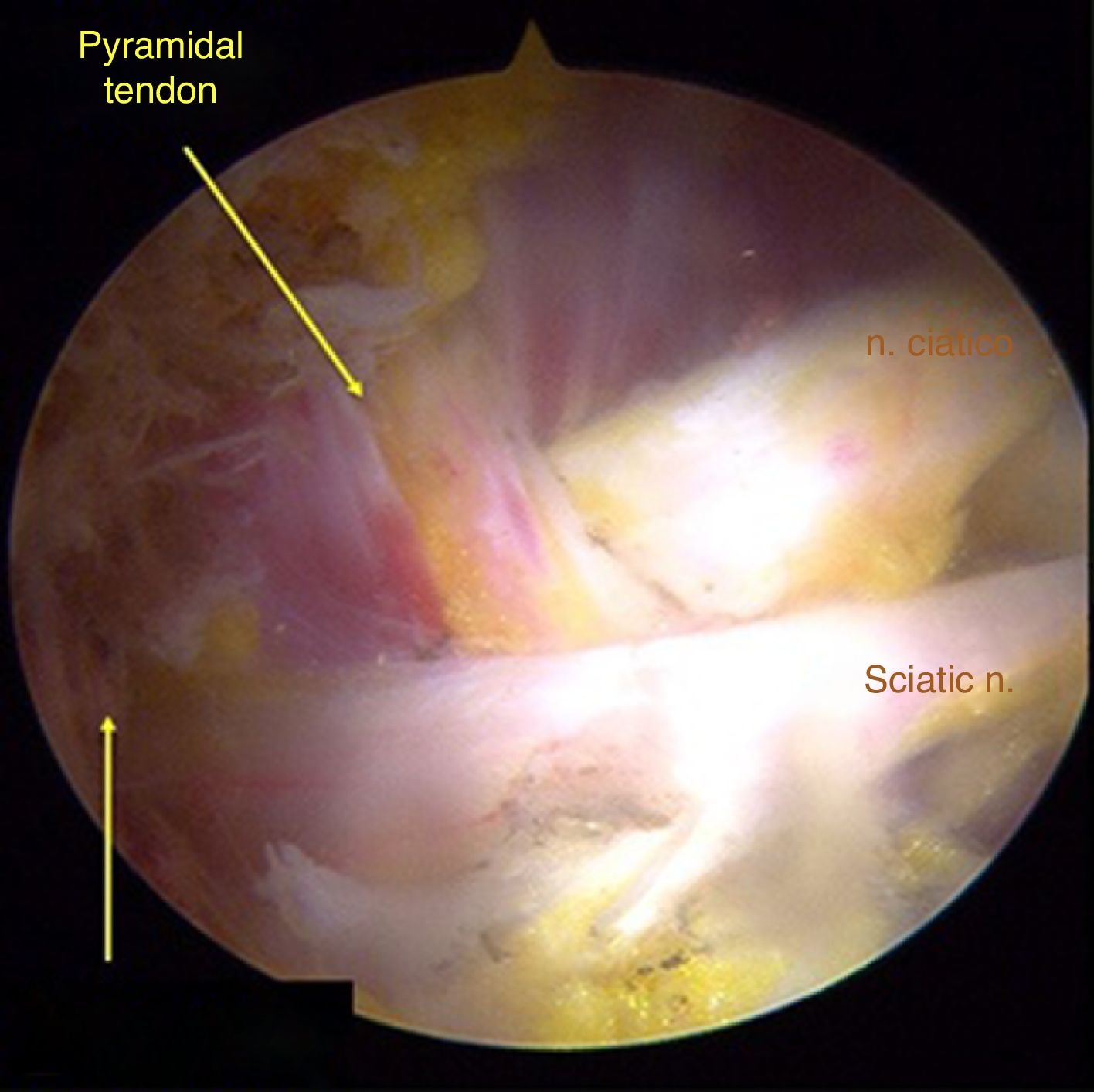

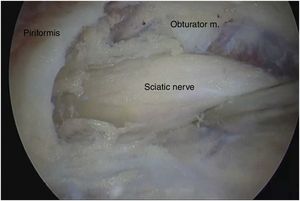

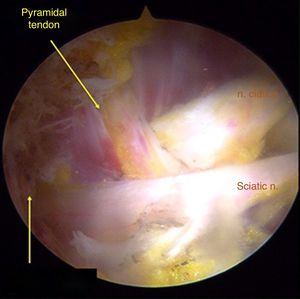

Surgical techniqueTo get to the DGS anterolateral portals, posterolateral portals and upper additional posterolateral portals with help from fluroscopy were made. The lens was inserted through the anterolateral portal, palpating the lateral wall of the greater trochanter and this was later slid along its posterior edge to insert into the DGS with a 30° lens (Fig. 3). Inspection of the DGS was begun proximal to the quadratus femoris muscle up to the greater sciatic notch (Fig. 4). The SN was identified by blunt dissection and the cause of entrapment visualised in order to proceed with release and verify mobility.

Anatomical findings of the SN were assessed, with regard to the number of lumen and relationship of the exit of the greater sciatic notch with the piriformis muscles, in keeping with the classification described by Beaton and Anson.7 To identify possible causes of entrapment, the pathogenic classification of fibrous/fibrovascular bands was used.14 Type I was when compression bands existed or a bridge which limited the anterior to posterior movement of the SN. Type II was when the adhesive tapes exercised lateral traction from the greater or medial trochanter to the sacrotuberous ligament and those which presented an indefinite distribution were classified as type III bands. Tenotomy was performed in cases where it became obvious that there was compression of the SN by the piriformis muscle and/or internal obdurator, with release being confirmed by dynamic tests to verify nerve movement.

Statistical analysisThe variables were summarised with mean, median, standard deviation and interquartile range. For the assessment of functionality and degree of pain, before and after intervention, the non-parametric Wilcoxon test was performed or the Student's t-test for paired data, in accordance with normality criteria. The Shapiro–Wilk test was used to assess adjustment to normal distribution. This analysis was performed in Stata® v.13 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas, USA).

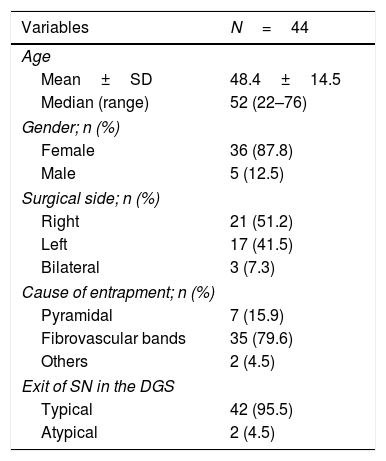

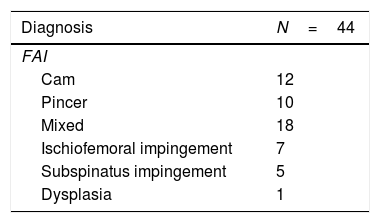

ResultsForty-four hips of 41 patients were included (36 females and 5 males) with an average age of 48.4±14.5 years. The stiff fibrovascular and hypertrophic bands were usually the reason for entrapment of the SN. The emergence of the SN from the pelvis had an exit pattern of a single lumen below the piriformis muscles in 42 hips (95.4%). Two (4.5%) patients presented with exit with an atypical pattern of a lumen through the piriformis muscles and another lumen below it (Fig. 5). In one isolated case, SN entrapment was attributed to the application of biopolymers in the gluteal region (Table 1). There was only one case of surgical intervention due to DGS without the presence of other conditions. Table 2 describes the associated diseases for all cases.

General characteristics.

| Variables | N=44 |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| Mean±SD | 48.4±14.5 |

| Median (range) | 52 (22–76) |

| Gender; n (%) | |

| Female | 36 (87.8) |

| Male | 5 (12.5) |

| Surgical side; n (%) | |

| Right | 21 (51.2) |

| Left | 17 (41.5) |

| Bilateral | 3 (7.3) |

| Cause of entrapment; n (%) | |

| Pyramidal | 7 (15.9) |

| Fibrovascular bands | 35 (79.6) |

| Others | 2 (4.5) |

| Exit of SN in the DGS | |

| Typical | 42 (95.5) |

| Atypical | 2 (4.5) |

DGS, deep gluteal space; SN, sciatic nerve.

Tenotomy of the piriformis muscles was performed in 21 (47.7%) hips, and in 10 (22.7%) tenotomy of the most internal obturator piriformis muscles was performed. Intraoperative findings revealed the finding of type I fibrovascular bands in 9 hips (25.7%); type II in 19 hips (54.3%) and type III in 13 hips (37.1%).

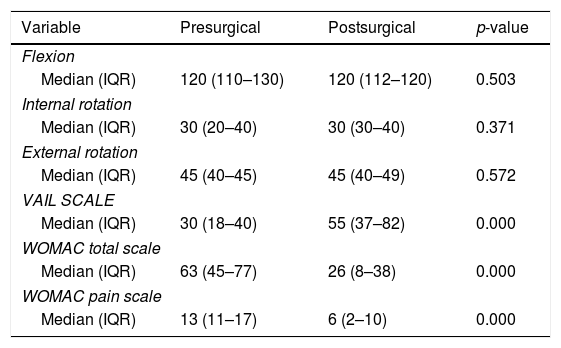

No statistically significant changes were found in the internal, external and flexion rotation angles after surgical intervention (p>0.05). The median score of the pain component on the presurgical WOMAC scale was 13 and in postoperative controls, it was 6. This represents a reduction of 54% with a statistically significant improvement (p<0.05). Total WOMAC scale scores presented a median of 63 points in presurgery with a reduction of 37 points at the end of follow-up, equivalent to an improvement of 58%. The VAIL scale showed a presurgical score of 30 points compared with a postsurgical score of 55 points (p<0.05) (Table 3).

Assessment of range of movement, functionality and pain before and after surgery.

| Variable | Presurgical | Postsurgical | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Flexion | |||

| Median (IQR) | 120 (110–130) | 120 (112–120) | 0.503 |

| Internal rotation | |||

| Median (IQR) | 30 (20–40) | 30 (30–40) | 0.371 |

| External rotation | |||

| Median (IQR) | 45 (40–45) | 45 (40–49) | 0.572 |

| VAIL SCALE | |||

| Median (IQR) | 30 (18–40) | 55 (37–82) | 0.000 |

| WOMAC total scale | |||

| Median (IQR) | 63 (45–77) | 26 (8–38) | 0.000 |

| WOMAC pain scale | |||

| Median (IQR) | 13 (11–17) | 6 (2–10) | 0.000 |

IQR, interquartile range.

A complication occurred which was persistent pain in the sensitive area of the femoral cutaneous nerve after surgery. Four revision operations were performed after 6 months with satisfactory results at the end of follow-up.

DiscussionDiagnosis of SN entrapment is still a challenge for the orthopaedic surgeon. DGS is dynamic in behaviour, which makes it difficult to find diagnostic methods that enable appropriate identification. Due to the above, a detailed physical examination and the assessment of images to rule out possible radiculopathies of intrapelvic origin are necessary as part of the study of this disease, with the use of a standardised management programme for this (Fig. 2). Despite the fact that in the majority of cases the entrapment of the SN in DGS responds well to conservative management, the persistence of clinical symptoms requires a search for other forms of management which are safe and reproducible in patients.

Benson and Schutzer (1999) described peripheral SN entrapment of post-traumatic origin, by the piriformis muscle and recommended that surgical procedure be considered in cases of persistence of pain after conservative therapy had been tried.8 Later, in 2003, Dezawa et al. described favourable outcomes in a series of six cases, in which a percutaneous release of the piriformis muscles was made to relieve the single cause of SN entrapment.10 In 2011, Martin et al. produced the description of DGS, establishing anatomical limits with its elements (Fig. 1) and they recognised that other different causes of entrapment beyond that of the piriformis muscle could exist, such as the fibrovascular bands, the internal obturator muscles and the calves. Our findings concur with those reported by Martin et al., since the majority of cases of entrapment were attributed to the presence of fibrovascular bands as the main compression agent of the SN, followed by cases which required tenotomy of the piriformis muscle.1 In 2012, Pérez-Carro et al.15 published their preliminary experience in six cases with the Martin et al.1 technique, with favourable results and an improvement on the modified Harris scale of 56–84 points after surgery to an average follow-up of 6 months.

In our cohort of patients, there was some relief in the level of pain after the endoscopic procedure. The WOMAC and VAIL scales indicated an improvement in function, similar to that reported in the Martin et al. study, in which functionality was assessed with the Harris Hip Score (mHHS) scale. There was a score of 78±14.1 points in a follow-up period of 6–24 months after surgery, representing an increase of 43% in the mean score of the mHHS compared with before surgery. Park et al., in a 24-month follow-up, found that after endoscopic decompression of the SN, 90% of their patients improved in presurgical symptoms, and specifically in the ability to remain seated for over 30min at a time and the presence of paresthesias.12 Carro et al.7, in a review of 52 cases to a mean follow-up of 17 months, found there were good to excellent results in 75% (39) of cases with an improvement in the mHHS of 52–79 points after endoscopic release of the SN. In the remaining 13 cases, an improvement in symptoms was reported, but this patient group continued to use analgesics.

In our experience, detailed knowledge of DGS anatomy and possible causes of entrapment have been essential factors to ensure success of the procedure. Since the space where surgery is performed is virtual, it is preferred that nerve release is carefully performed with a blunt tool so as not to affect the vascular structures of the fibrous bands and therefore avoid the presence of bleeding which may easily discontinue surgery from visual field impairment. The posterior femoral cutaneous nerve must first be identified, in order to avoid injuring it. This is always found anterior and medial to the SN.

It is important not to release any more nerve than is necessary and to carry out early movement of the joint to prevent trapping the nerve again due to the presence of scars. This occurred in our cohort where revision cases were due to the entrapment of the SN by scar tissue. These patients presented with a recurrence of pain within the 6-month period associated in all cases with the lack of early movement of the SN because of postoperative pain.

It is also important to monitor the time and pressure of the infusion pump during surgery since the sciatic notch is a direct canal in the intra-abdominal region which could increase the risk of producing extravasations of liquid into the abdomen.

DGS release was performed as a single procedure only in one case. The remaining patients required additional procedures for associated diseases such as femoroacetabular impingement, ischiofemoral impingement and dysplasia plus periacetabular osteotomy. Although a positive result was obtained in all patients in the diagnostic test of the blocking of the SN in the DGS, it is not possible to assert that the patient had a reduction in pain from the management of these diseases or from the release of the SN.

One of the weaknesses of this study is the small patient sample. However, this serves as a base to complement the scarcity of knowledge regarding DGS management. Another weakness is related to the use of the WOMAC and VAIL scales for assessing the patients’ functional outcomes, which impedes comparison with other series where they use the mHHs scale. These were implemented because they had cultural validation into Spanish and are commonly used in our environment. Furthermore, at present, no specific scale is available for the assessment of symptoms associated with DGS. Prospective studies with long-term follow-up are essential to objectively discover the results obtained with endoscopic management including an assessment based on scales of function and pain, so that algorithms and/or protocols may be standardised when managing SN entrapment.

Finally, we would conclude that the endoscopic release of the SN is an alternative in DGS management as it improves function and reduces the level of pain when accurate patient selection is made.

Level of evidenceLevel of evidence IV.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

We would like to thank the Institute of Research of the Imbanaco Medical Centre for their support during the development of this project.

Please cite this article as: Aguilera-Bohorquez B, Cardozo O, Brugiatti M, Cantor E, Valdivia N. Manejo endoscópico del atrapamiento del nervio ciático en el síndrome de glúteo profundo: resultados clínicos. Rev Esp Cir Ortop Traumatol. 2018;62:322–327.