In the Spanish population, previous studies related to mortality after hip fracture are based on patients aged 60–102 years and did not stratify patients according to the type of fracture. The objective of this study was to identify the factors with influence on mortality at one postoperative year in patients aged 80 years or older after a femoral neck fracture.

Material and methodRetrospective study of cases and controls. Consecutive patients operated between 2015 and 2016 were included. Baseline characteristics, medical history and previous medication, analytical parameters, Charlson index, ASA scale, Barthel index and Pfeiffer questionnaire were studied. Surgical data and complications were recorded during follow-up. Survival was assessed by the Kaplan–Meier method and the variables that affected it by Cox regression.

ResultsMortality one year postoperatively was 21.1% and mean survival 10.3months (95% CI: 9.7–10.9). The Cox regression showed that age >87years, Barthel score≤85 and the combination of anticoagulants with INR≥1.5 were significant predictors of mortality during the first year of follow-up.

ConclusionThe predictors of mortality during the first postoperative year after femoral neck fracture in octogenarian or older patients were: age >87years, physical dependence measured by a Barthel index score≤85, and the use of anticoagulants with a INR≥1.5 at admission.

En la población española los estudios previos relacionados con la mortalidad tras fractura de cadera están basados en pacientes con edades entre 60 a 102años y no estratificaban los pacientes de acuerdo con el tipo de fractura. El objetivo de este estudio fue identificar los factores con influencia sobre la mortalidad al año postoperatorio en pacientes de 80años o más que sufrieron una fractura cervical de cadera.

Material y métodoEstudio retrospectivo de casos y controles. Fueron incluidos los pacientes consecutivos intervenidos entre 2015 y 2016. Se estudiaron las características basales, los antecedentes y la medicación previa, los parámetros analíticos, el índice de Charlson, la escala ASA, el índice de Barthel y el cuestionario Pfeiffer. Se registraron los datos quirúrgicos y las complicaciones durante el seguimiento. La supervivencia se evaluó mediante el método de Kaplan-Meier y las variables que la afectaban mediante la regresión de Cox.

ResultadosLa mortalidad al año postoperatorio fue del 21,1% y la supervivencia media de 10,3meses (IC95%: 9,7-10,9). La regresión de Cox mostraba que la edad >87años, la puntuación de Barthel ≤85 y la combinación de anticoagulantes con INR ≥1,5 eran predictores significativos de mortalidad durante el primer año de seguimiento.

ConclusiónLos factores predictores de mortalidad durante el primer año postoperatorio por fractura cervical de cadera en pacientes octogenarios o mayores fueron la edad >87años, la dependencia física medida a través de una puntuación en el índice de Barthel ≤85 y el uso de anticoagulantes con un INR ≥1,5 al ingreso.

Patient mortality at one year after suffering a hip fracture in the Spanish population varies from 13% to 30% in recent studies.1,2 These studies suggest numerous factors associated with the increase in mortality of elderly patients after hip fractures. These are chiefly age,3–6 male sex,7,8 comorbidities,7,9 delayed surgery,4,8 previous level of independence3,5 and cognitive state.2,3 Age is the most commonly described risk factor for mortality in the majority of studies of the Spanish population.3–6 Nevertheless, these studies are based on series of hip fracture patients with a broad age range, from 60 to 102 years old. Likewise, the majority of studies do not stratify patients according to type of hip fracture.

The increase in life expectancy in the Spanish population has led to an increasing number of hip fractures in octogenarian patients.9 This gives rise to a challenge for surgeons, given that age is associated with fewer vital reserves and a higher number of more severe comorbidities.10 On the other hand, a multicentre study11 found a rate of cervical fractures (47%) only slightly lower than trochanter fracture (53%). The majority of cervical fractures were treated by hip arthroplasty, which involves greater surgical aggression.

However, we understand that no studies of Spanish patients have centred on mortality in octogenarians with a cervical hip fracture. Only 3 studies focussed on patients with cervical fractures,6,12,13 they ranged in age from 62 to 97 years old. Additionally, one of these studies12 analysed the influence of previous antiplatelet treatment, and another study13 was of patients operated using total hip arthroplasty. Thus there is very little data in the Spanish literature on octogenarians with cervical hip fracture.

This study aimed to identify the factors that influence mortality in the year after surgery in patients aged 80 years old or more who suffered a cervical hip fracture.

Material and methodsA retrospective study of cases and controls was designed, and it was approved by our institutional ethics committee; no informed consent was required as it was considered to be an assessment of clinical practice. Patients treated surgically for cervical hip fracture from February 2015 to December 2016 were identified in the departmental database, with the inclusion criterion of age of at least 80 years old. To adapt this to habitual practice, the only exclusion criterion was pathological fracture due to a tumoral process. 156 patients who fulfilled the criteria were identified, of whom 33 died during the first year of follow-up after surgery (the study group, mortality) while 123 survived after one year (the control group, survivors).

Mortality data were extracted from the computerised institutional records of our community, such as the hospital clinical management system (Orion), the outpatient clinical management system (Abucasis) and the electronic health history (EHH). By using a personal identification number (SIP) it was possible to reconstruct the whole medical history of a patient.

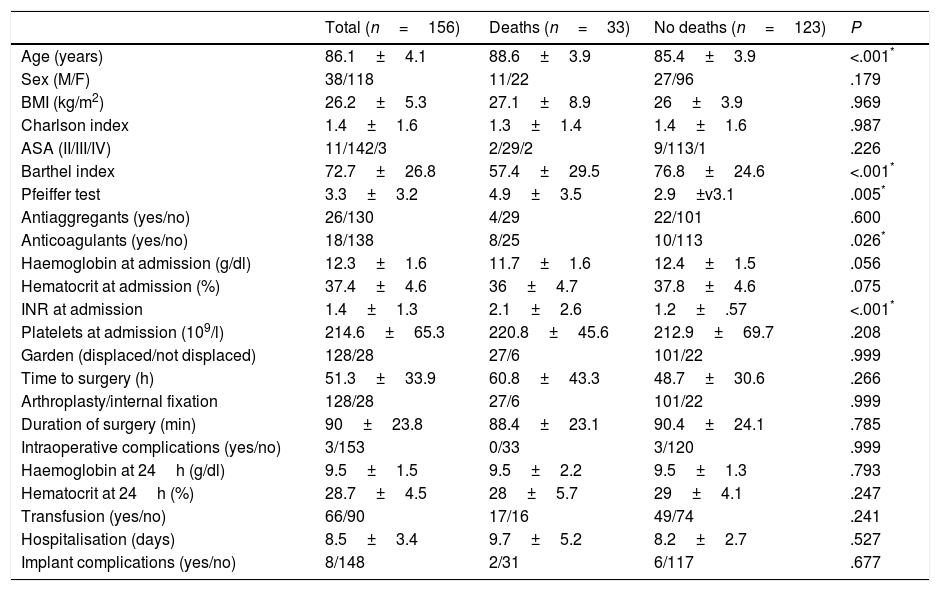

There were 22 women and 11 men in the mortality group, with an average age of 88.6 years old (range, 82–95 years old). There were 96 women and 27 men in the control group, with an average age of 85.4 years old (range, 80–95 years old). The characteristics of both groups are shown in Table 1.

Patient and group characteristics.

| Total (n=156) | Deaths (n=33) | No deaths (n=123) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 86.1±4.1 | 88.6±3.9 | 85.4±3.9 | <.001* |

| Sex (M/F) | 38/118 | 11/22 | 27/96 | .179 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26.2±5.3 | 27.1±8.9 | 26±3.9 | .969 |

| Charlson index | 1.4±1.6 | 1.3±1.4 | 1.4±1.6 | .987 |

| ASA (II/III/IV) | 11/142/3 | 2/29/2 | 9/113/1 | .226 |

| Barthel index | 72.7±26.8 | 57.4±29.5 | 76.8±24.6 | <.001* |

| Pfeiffer test | 3.3±3.2 | 4.9±3.5 | 2.9±v3.1 | .005* |

| Antiaggregants (yes/no) | 26/130 | 4/29 | 22/101 | .600 |

| Anticoagulants (yes/no) | 18/138 | 8/25 | 10/113 | .026* |

| Haemoglobin at admission (g/dl) | 12.3±1.6 | 11.7±1.6 | 12.4±1.5 | .056 |

| Hematocrit at admission (%) | 37.4±4.6 | 36±4.7 | 37.8±4.6 | .075 |

| INR at admission | 1.4±1.3 | 2.1±2.6 | 1.2±.57 | <.001* |

| Platelets at admission (109/l) | 214.6±65.3 | 220.8±45.6 | 212.9±69.7 | .208 |

| Garden (displaced/not displaced) | 128/28 | 27/6 | 101/22 | .999 |

| Time to surgery (h) | 51.3±33.9 | 60.8±43.3 | 48.7±30.6 | .266 |

| Arthroplasty/internal fixation | 128/28 | 27/6 | 101/22 | .999 |

| Duration of surgery (min) | 90±23.8 | 88.4±23.1 | 90.4±24.1 | .785 |

| Intraoperative complications (yes/no) | 3/153 | 0/33 | 3/120 | .999 |

| Haemoglobin at 24h (g/dl) | 9.5±1.5 | 9.5±2.2 | 9.5±1.3 | .793 |

| Hematocrit at 24h (%) | 28.7±4.5 | 28±5.7 | 29±4.1 | .247 |

| Transfusion (yes/no) | 66/90 | 17/16 | 49/74 | .241 |

| Hospitalisation (days) | 8.5±3.4 | 9.7±5.2 | 8.2±2.7 | .527 |

| Implant complications (yes/no) | 8/148 | 2/31 | 6/117 | .677 |

All interventions were performed under spinal anaesthesia. Non-displaced cervical fractures (Grade I–II)14 were treated by internal fixation (28 patients), and displaced fractures (Grade III–IV) were treated by hemiarthroplasty (128 patients). None of the patients received a total hip arthroplasty (THA) as the primary treatment.

Internal fixation was performed in situ without previous reduction, using 2–3 cannulated titanium screws percutaneously. They are partially threaded and have a diameter of 6.5mm (AsnisTM III, Stryker Trauma, Switzerland). In a standardised way these patients were allowed to sit up 24h after the operation, and to load the joint 6 weeks later after a radiographic check. The approach was posterolateral in the patients with hemiarthroplasty, using a prosthesis fixed with cement in all of the patients. In all of the patients a vacuum drainage was put into place for 48h. Sitting up and loading the joint were permitted as standard 24h after surgery, after a radiographic check.

All of the patients received standardised antibiotic and antithrombotic prophylaxis. Blood transfusion was indicated if haemoglobin was <8g/dl or <9g/dl in the presence of symptomatic anaemia or in patients with cardiopathy.

Follow-up and evaluationThe main variable in the result was mortality within one year after surgery. On admission, all of the patients were evaluated by a surgeon, an anaesthetist and an orthogeriatrician. Comorbidities at the moment of admission were evaluated using the Charlson index15 and the risk scale of the American Society of Anaesthetists (ASA).16 Their degree of independence for everyday life activities was evaluated using the Barthel index,17 and their cognitive state was assessed using the Pfeiffer questionnaire.18 After discharge the patients were assessed in a standard way at 1, 3, and 6 months after surgery, and at least at 12 months. Surgical delay was defined as the hours that had elapsed after trauma prior to the operation.

Surgical data and complications during follow-up were recorded. Infection of the surgical site was defined according to internationally agreed criteria.19 Radiological assessment was performed using standard anteroposterior and axial projections of the hip. Failure of the internal fixation included displacement secondary to the fracture, disassembly of the implant, intraarticular protrusion or breakage of the screws. Pseudoarthrosis was considered if after 6 months there was no radiological evidence of consolidation, understood as bone bridges in at least 3 of 4 cortical points in orthogonal projections. The diagnosis of avascular necrosis of the femoral head (ANFH) was made using simple X-rays and defined as any sign of necrosis above Steinberg stage II.20

Statistical analysisStatistical analysis was performed using the SPSS v.22 and MedCalc v.13 programmes. Normalcy was tested using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. The Student t-test was used to evaluate continuous variables or the non-parametric Mann–Whitney U test. The association between categorical variables was evaluated using Fischer's exact test or the Mantel–Haenszel non-parametric test.

The continuous variables that showed significant differences between groups in univariate analyses were transformed into dichotomic variables after determining the point of the area under the curve (AUC) with the greatest precision using receptor operative characteristics (ROC) analysis. Patient survival was evaluated using the Kaplan–Meier method. The influence of dichotomic variables that showed significant differences between groups on survival was evaluated using the log-rank test. The variables that were significant as modifiers of survival time were entered in a multivariate Cox regression model, expressing data as the hazard ratio (HR) with a 95% confidence interval. The predictive value of the model for mortality during the first year of follow-up was evaluated by the AUC. All of the tests considered a bilateral level of significance of P to be less than .05.

ResultsMortality one year after surgery (Fig. 1) stood at 21.1%, with an average survival time of 10.3 months (CI 95%: 9.7–10.9). The causes of death during the first year are shown in Table 2. Two patients in the group of those who died had to be operated again, one due to ANFH after a non-displaced fracture operated using hemiarthroplasty, while the other had luxation of the prosthesis that required open reduction. Three patients in the control group had intraoperative complications, with two failures of the cement–prosthesis interface (non-adherence of the rod) and there was one periprosthesis fracture. Six other patients in the control group had to be operated again, one due to infection, one because of failure of the internal fixation, two due to luxation of the prosthesis, one for later periprosthesis fracture and one due to ANFH.

In the univariate analyses (Table 1) the mortality group had a significantly older average age (P<.001), less independence according to the Barthel index (P<.001) and poorer cognitive state according to the Pfeiffer test (P=.005). 32% of the patients in the mortality group were taking anticoagulants vs. 8.8% in the control group (P=.026), and thus the INR at admission was significantly greater in the mortality group (P<.001). No other significant differences were found between the groups.

According to the area under the ROC curve, the most precise cut-off points for these variables with significant differences were age >87 years old (sensitivity: 60.6%; specificity: 74.8%), Barthel score ≤85 (sensitivity: 87.9%; specificity: 45.5%), and >5 mistakes in the Pfeiffer test (sensitivity: 60.6%; specificity: 75.6%). Respecting the INR, the cut-off point was placed at ≥1.5 as this is the cut-off point for normalcy in the laboratory of our hospital. Table 3 shows how these cut-off points significantly affected individual survival during the first year.

Factors associated with survival for groups.

| n | Survival | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||

| >87 years old | 51 | 8.7 (7.4–10) | |

| ≤87 years old | 105 | 11 (10.5–11.6) | <.001 |

| Barthel | |||

| ≤85 | 96 | 9.5 (8.6–10.4) | |

| >85 | 60 | 11.5 (11–12) | .001 |

| Pfeiffer | |||

| >5 | 56 | 9.1 (7.8–10.3) | |

| <5 | 100 | 10.9 (10.4–11.5) | .001 |

| Anticoagulants | |||

| Yes | 18 | 7.7 (5.5–10) | |

| No | 138 | 10.6 (10–11.2) | .004 |

| INR | |||

| ≥1.5 | 20 | 7.2 (5.1–9.3) | |

| <1.5 | 136 | 10.7 (10.1–11.3) | <.001 |

| Anticoagulants*INR | |||

| ≥1.5 | 17 | 7.5 (5.1–9.8) | |

| <1.5 | 139 | 10.6 (10–11.2) | .002 |

Survival: average in months (CI 95%).

For the multivariate analysis we considered that there was a direct relationship between patients who take anticoagulants and those who had INR≥1.5, so that both models were entered in the model as an interaction (taking anticoagulants*INR≥1.5 vs. those who did not fulfil these criteria as a whole). The Cox regression model (Table 4) showed that age >87 years old, a Barthel score≤85 and the combination of anticoagulants with INR≥1.5 were significant predictors of mortality during the first year of follow-up. The discriminatory capacity of the model according to its AUC was 0.61 (CI 95%: .51–.72).

Mortality predictors in multivariate analysis.

| Coefficient | HR (CI 95%) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 1.294 | ||

| ≤87 years old | Ref. | ||

| >87 years old | 3.6 (1.7–7.4) | <.001 | |

| Barthel index | 1.400 | ||

| ≥85 points | Ref. | ||

| ≤85 points | 4.0 (1.2–12.7) | .017 | |

| Pfeiffer test | .514 | ||

| <5 mistakes | Ref. | ||

| >5 mistakes | 1.6 (.7–3.6) | .190 | |

| INR≥1.5*Anticoagulants | 1.220 | ||

| No | Ref. | ||

| Yes | 3.3 (1.4–7.6) | .003 | |

HR: hazard ratio; CI: confidence interval; Ref: reference (HR=1).

Mortality in the first year after surgery in the cohort of 156 patients in this study amounted to 21.1%. This figure is similar to those found in other studies.3–8,21 Our study found that the significant factors for the risk of mortality were age above 87 years old, independence of ≤85 Barthel index points at the time of admission, and the administration of anticoagulant medication prior to admission, with an INR≥1.5.

Numerous risk factors for mortality following hip fracture have been suggested for the Spanish population, although the majority of studies do not agree on them.1–8 The most sensitive predictor in this study was the Barthel index, which evaluate the functional state of frail elderly individuals. Together with the Charlson index, other authors22 consider it to be one of the main prognostic factors. Other studies have also found the Barthel index to be a prognostic factor for mortality after hip fracture.23,24 Aranguren et al.5 identified the Barthel index as the mortality predictor at 90 days and 1 and 2 years, establishing a cut-off point at 60 points that separated patients with severe or total dependency from those who were less dependent. In our study the cut-off point was calculated statistically to represent the highest specificity and sensitivity, so that the cut-off point at ≤85 includes some of the patients with moderate dependency. The study by Folbert et al.24 on hip fractures in general, found that together with the Barthel functional state index, variables associated with mortality within one year included male sex, advanced age, an ASA score of III or more, a high score in the Charlson index, malnutrition and previous physical limitations. On the contrary, Blay et al.25 observed that the Barthel index was not a significant predictor of mortality within one year after hip fracture.

The multivariate analysis of our study found a significant association between mortality and anticoagulant medication with an increase in the INR. Of all the factors analysed, this was the one that led to the greatest reduction in average survival time. No previously published study of the Spanish population studied the association between the use of anticoagulant medication and postoperative mortality. Sánchez et al.4 excluded anticoagulated patients when they studied the influence of surgical delay due to organisational reasons. Although Rodríguez et al.8 included anticoagulated patients, they did not consider this variable to be a potential risk factor. Mas et al.23 and Agudo et al.12 observed that platelet antiaggregation was significantly associated with mortality in hip fracture patients, although they excluded anticoagulated patients. Lizaur et al.1 found a significant association between the use of anticoagulants and increased delay until surgery, although this was not significantly associated with mortality.

This study found that although age was a risk factor for mortality, the fact that the cohort studied was over the age of 80 years old must be taken into account. Age has usually been said to be a risk factor for mortality within one year for hip fracture patients4–7 in studies of patients aged over 64 years old. The studies by González et al.,2 Aranguren et al.5 and Navarrete et al.7 analysed age dichotomised according to arbitrary cut-off points, in groups of patients younger and older than 83, 86 and 85 years old, respectively. It is possible to think that in patients younger than these ages the risk of death falls, especially because the series contained very young patients, while their average ages had a very broad standard deviation. In our study, an age over 87 years old best explained deaths in the first year, with a suitable ratio of sensitivity and specificity. These patients had a risk of dying during the first year 3.6 times greater than the younger patients, and death occurred within an average postoperative time interval of 8.7 months.

Respecting the limitations of our study, we have to underline those which are intrinsic to any retrospective study. The sample size, which was limited in time in our study, means that its results should be taken with precaution in terms of the risk factors found. Nevertheless, multivariate analysis of the variables that were found to be significant was used to attempt to minimise the risk of possible distortion.

ConclusionsWith the available data, the predictor factors of mortality during the first year after surgery for hip fracture in octogenarian or older patients were an age greater than 87 years old, a physical dependency score measured using the Barthel index≤85 and the use of anticoagulants with an INR≥1.5 at admission. These parameters are easy to measure and make it possible to identify elderly patients with a poorer prognosis who may benefit from more exhaustive care.

Level of evidenceLevel of evidence III.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Please cite this article as: Novoa-Parra CD, Hurtado-Cerezo J, Morales-Rodríguez J, Sanjuan-Cerveró R, Rodrigo-Pérez JL, Lizaur-Utrilla A. Factores predictivos de la mortalidad al año en pacientes mayores de 80 años intervenidos de fractura del cuello femoral. Rev Esp Cir Ortop Traumatol. 2019;63:202–208.