To describe our series of patients with giant cell tumor of bone with a long-term follow-up to show the results obtained with our treatment protocol.

Materials and methodsA total of 97 histologically confirmed giant cell tumors of bone were treated in our center between 1982 and 2009. The mean follow-up period was 12 years (2–27 years). The treatment received was determined by the radiological grade based on the Campanacci classification. The series consisted of 53 women (54.6%) and 44 men (54.4%) with a median age of 34.16 years (15–71 years). The data collected was focused on the clinical presentation, location, phase, extension, recurrences, and complications.

ResultsThe treatment most used in Campanacci grades i and ii was intralesional excision with high-velocity drilling and filling with a graft. In grades iii that could not be treated with the aforementioned method, it was decided to perform en bloc resection. An overall recurrence rate of around 25.8% was observed. Seven cases (7.2%) presented with a recurrence of the malignancy. The death rate at the end of follow-up was 2.1% (2 cases).

ConclusionsCurettage with a high-velocity drill and a bone graft in giant cell tumor of bone Campanacci grades i and ii obtains good results after long-term follow-up. Some grade iii giant cell tumors of bone that cannot be treated with this therapeutic option require en bloc resection and reconstruction.

Describir una serie de tumores óseos de células gigantes con largo seguimiento, mostrando los resultados obtenidos con nuestro protocolo terapéutico.

Material y métodoEntre 1982-2009, 97 pacientes con lesiones histológicamente confirmadas como tumores óseos de células gigantes fueron tratados en nuestro centro con un seguimiento medio de 12 años (2-27 años). El tratamiento recibido lo determinó la clasificación de Campanacci. La serie la formaron 53 mujeres (54,6%) y 44 hombres (54,4%) con una edad media de 34,16 años (15-71 años). Los datos recogidos se centraron en la presentación clínica, localización, estadio, extensión, recurrencias y complicaciones.

ResultadosEl tratamiento más utilizado en los estadios i y ii de Campanacci fue escisión intralesional con fresado a alta velocidad y rellenado con injerto homólogo, mientras que en los estadios iii que no podían ser tratados con este método se abogó por la resección en bloque. Se halló una recurrencias global del 25,8%. Siete casos (7,2%) presentaron malignización. La tasa de exitus fue del 2,1% (2 casos).

ConclusiónLa opción terapéutica presentada para los tumores óseos de células gigantes que consiste en legrado con fresado a alta velocidad y aporte de injerto óseo en los grados i y ii de Campanacci obtiene resultados comparables con literatura actual. Los tumores de grado iii, que no pueden ser tratados con la opción terapéutica mencionada anteriormente, requieren resección en bloque y reconstrucción posterior.

Giant cell tumor of bone (GCTB) accounts for between 3% and 5% of primary bone tumors and 20% of benign bone tumors.1 It was classified histologically by Jaffe et al.2 and radiographically by Campanacci.3 It mainly appears between the second and fourth decades of life, usually in the epiphysis of long bones, with a locally aggressive behavior, and its clinical evolution is difficult to predict.4

Radiographic exploration shows an excentric metaphysoepiphyseal lithic lesion with a geographic pattern. The aspect of the edges of the tumor may vary from well-defined margins with a sclerous edge to poorly defined margins which reduce and destroy the cortical until the bone fractures.

Surgical treatment is necessary and controversial, as there are various different surgical options. Therefore, it is advisable to classify the tumors into Campanacci grades through a radiographic study.3 Thus, grade i and ii cases may be treated by intralesional resection through curettage and high-speed drilling and graft and/or cement. In grade iii cases, with significant cortical destruction, it is advisable to carry out a block resection with reconstruction (megaprosthesis or osteoarticular graft) if the location requires it.

The objective of this review was to describe a series of GCTB with a long follow-up period, showing the results obtained with a specific treatment protocol.

Materials and methodsWe conducted a retrospective study of a series of cases treated between September 1982 and April 2009 from the records of University Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau, in Barcelona, Spain. We included all the patients with a diagnosis of GCTB confirmed by anatomopathological analysis and excluded those for whom the clinical records were not complete. An oncological orthopedic surgeon, together with a radiologist specializing in the musculoskeletal system, analyzed all the cases. These data focused on the clinical presentation, location, classification, extension, recurrences, complications and evolution.

We studied 97 patients with a mean follow-up period of 12 years (range: 2–27 years). The series was comprised of 53 females (54.6%) and 44 males (45.4%), with a mean age at the time of diagnosis of 34.16 years (range: 15–71 years). All the patients were studied by simple radiographs and stratified according to the Campanacci classification,3 with 15 (15.5%) grade i cases, 70 (72.1%) grade ii cases and 12 (12.4%) grade iii cases (Table 1). The locations are shown in Fig. 1. The initial clinical presentation was pain in 85 patients (87.6%), pathological fracture in 3 cases (3.1%), painless mass in 2 cases (2.1%) and an accidental finding in 7 cases (7.2%). The surgical treatment of primary GCTB was curettage in 71 cases (73.2%) in Campanacci stages i and ii and 26 block resections (26.8%) in stage iii or when it was considered that curettage was technically unfeasible.

Description of the series of giant cell tumor of bone cases presented.

| Campanacci stage | Patients (n=97) | Treatment | % First recurrence | Survival (%) |

| I | 15 | Curettage (n=15) | 20 (3 patients) | 100 |

| II | 70 | Curettage (n=56) | 30.4 (17 patients) | 98.2 (1 patient) |

| Block resection (n=14) | 14.3 (2 patients) | 100 | ||

| III | 12 | Block resection (n=12) | 25 (3 patients) | 91.7 (1 patient) |

The table shows the percentage of first recurrences classified by Campanacci groups and type of treatment applied.

The bone defect resulting from curettage was filled with homologous cancellous graft in 61 cases (85.9%) and autogenous in 10 cases (14.1%). The defect resulting from block resection was reconstructed with a structural graft in 3 cases (11.5%), with cancellous homograft in 5 cases (19.2%) and with autograft in 2 cases (7.8%). The remaining 16 cases (61.5%) did not require it. A total of 58 (59.8%) patients did not require additional osteosynthesis or prosthetic reconstruction, 28 (28.9%) required osteosynthesis with plates and screws and 11 (11.3%) required placement of a reconstruction prosthesis.

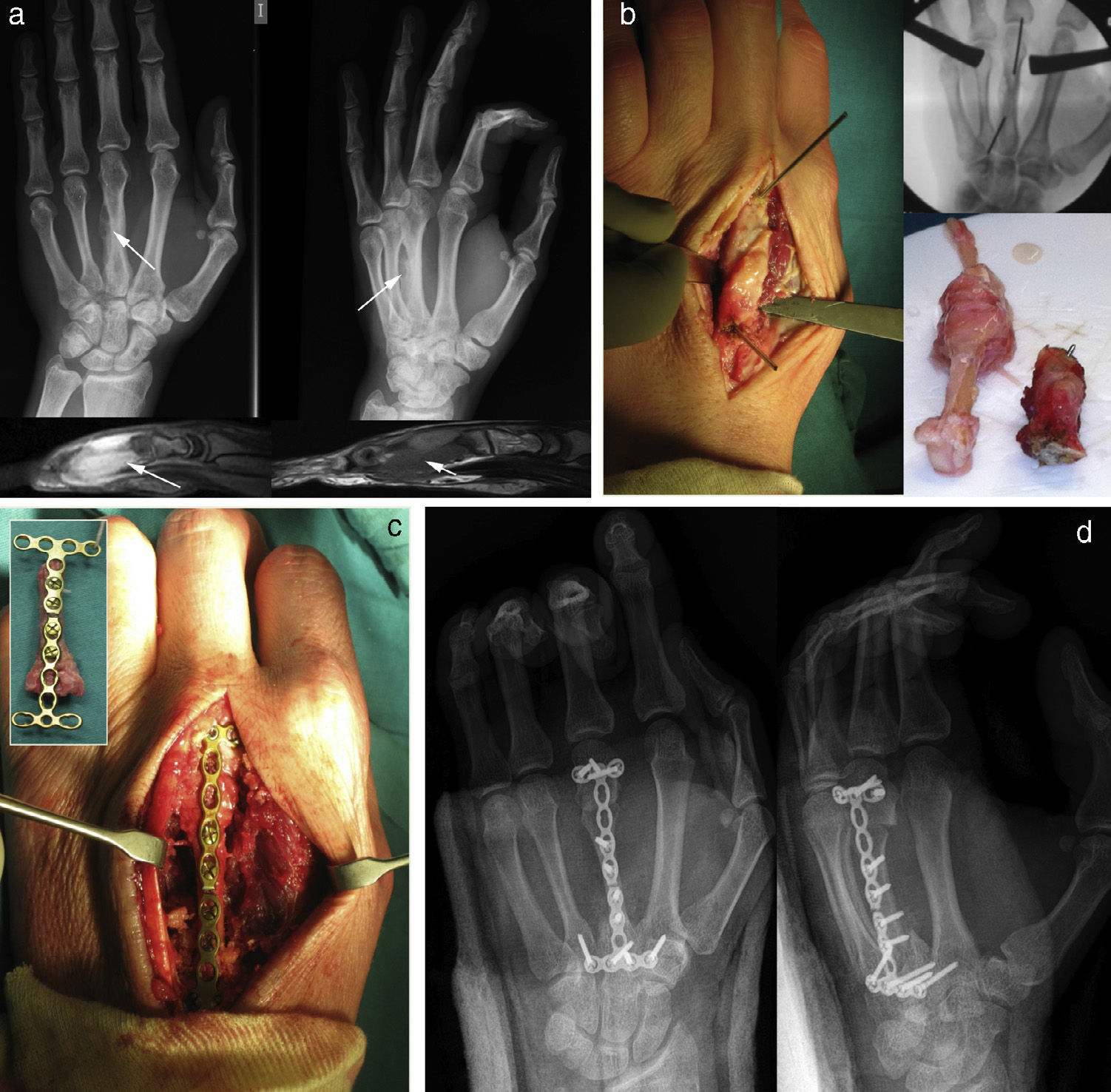

The curettage (Fig. 2) and block resection (Fig. 3) techniques followed the general oncological pathology guidelines. We obtained intra- and postoperative radiographs in all cases. In the postoperative period, patients followed an antibiotic protocol with 1g/8h cefazolin for 3 days. Patients were clinically and radiographically reviewed at 3, 6 and 12 months from the intervention, and annually thereafter.

Composition of a distal femoral GCTB. (a) The anteroposterior and lateral simple radiograph images show an excentric, metaphysoepiphyseal lithic lesion in the internal femoral condyle, which thins out the cortical without breaking it, with poorly defined margins and no periosteal reaction. (b) Treatment through intralesional resection by aggressive curettage and high-speed drilling. (c) Fragmented homologous cancellous graft and structural corticocancellous in marquetry, fixed with screws. d) Evolution control through simple radiographs showing a correct integration of the graft.

Composition of a GCTB of the third metacarpal which recurred after curettage 6 months earlier. The image shows the treatment through block resection and reconstruction with interposed graft. (a) Simple radiograph showing an expansive lithic lesion in the third metacarpal, which inflates and thins out the cortical. The magnetic resonance scan clearly shows soft tissue involvement. (b) Identification under scopy of the area affected by the tumor and marking with Kirschner wires. The lower right corner shows the bone graft prior to its section, along with the resection piece. (c) Prior reconstruction of the metacarpal intermediate graft with an osteosynthesis plate and screws for subsequent placement in the resection bed. (d) Subsequent radiographic control.

We obtained the number and percentage of cases for categorical variables, as well as the mean and standard deviation for quantitative variables. Relationships between variables were described using contingency tables and inferences were studied using the Chi-squared test, t test or Fisher's exact test, as applicable. We conducted a multivariate analysis, selecting those variables which had previously shown a trend toward significance (P<.20) applying logistic regression. The level of statistical significance was set at 5% (alpha=.05). We used the statistics software package SPSS (V15.0).

ResultsOncological resultsOut of the 97 patients with GCTB, 25 (25.8%) suffered local recurrence. Among the 71 patients who were treated by high-speed drilling and a cancellous graft, 20 (28.2%) suffered recurrence. Out of the 26 cases treated by block resection, 5 (19.2%) suffered recurrence. These first recurrences were treated by a new curettage (17 cases) or block resection (8 cases). Regarding recurrences in the block resection group, these appeared within 1 year in 92% of cases, decreasing to 70% after the third year. In the curettage group, 80% of recurrences appeared during the first year, decreasing to 58% after the third year.

The multivariate comparative study only found a statistically significant relationship (P=.047) between the type of surgery employed and the rate of recurrence with a mean time of recurrence of 120 months (range: 107–201 months). That is, grade iii GCTB cases which suffered recurrence did so earlier than grade i and ii cases.

Six cases with multiple recurrences were treated by radiotherapy (mean value of 45Gy) and chemotherapy (denosumab 120mg per month during the follow-up period) pre- and postoperatively. The reconstructions of recurrences initially used homologous cancellous grafts, followed by structural grafts and, lastly, autogenous grafts.

We observed 7 cases of malignization. These malignancies resulted in 1 case of intramedullary osteogenic sarcoma, 2 malignant fibrohistiocytomas, 1 low-grade fusocellular sarcoma, 2 osteosarcomas and 1 high-grade undifferentiated sarcoma. These 7 cases of malignization evolved with distant dissemination; 5 cases to the lungs, 1 to the dorsal rachis and 1 to the pleura. By the end of the follow-up period, 2 patients (2.1%) had died at 35 and 48 months, respectively. In addition, we observed 1 case of large tumoral expansion and found 1 massive giant cell tumor.

Radiographic resultsConsidering the classification of the osseointegration of the allografts of the International Society of Limb Salvage (ISOLS), the GCTB treated by high-speed drilling and cancellous graft (71 patients) presented excellent results in 88.7% (63 patients) of cases, good in 9.9% (7 patients) and acceptable in 1.4% (1 patient). Patients who underwent block resection with reconstruction by a graft (26 patients) showed an excellent osseointegration in 65.4% (17 patients) of cases, good in 19.2% (5 patients), acceptable in 3.9% (1 patient) and poor in 11.5% (3 patients). One case of osteoarticular graft in the distal radius in a patient with grade iii GCTB which did not integrate was fractured, as was another in the same location which presented radiocarpal arthrosis. Both cases required arthrodesis and extraction of the graft.

General complicationsWe observed 1 case of infection of the surgical wound in a grade iii GCTB in the femur which was treated by block resection and 1 case of septic loosening of a proximal tibial megaprosthesis. The patients were treated with antibiotic therapy alone or in combination with knee arthrodesis, respectively. None of the cases treated by drilling and grafting suffered a postoperative fracture, but 2 cases of grade ii GCTB in the femur which were treated by drilling recurred and presented pathological fracture. One case of block resection in the proximal fibula presented paralysis of the external popliteal sciatic nerve.

DiscussionAlthough GCTB accounts for 20% of benign bone tumors, its treatment is still controversial. It has been suggested that these tumors should be classified according to their Campanacci grades,3 in order to treat grade i and ii cases through intralesional resection by curettage with high-speed drilling plus a graft and/or cement, and grade iii cases with significant cortical destruction by block resection with reconstruction in cases requiring it.

For cases with grade i and ii GCTB, the authors preferred high-speed drilling as the main option, taking into account that both liquid nitrogen and phenol have shown good results regarding local recurrences. Liquid nitrogen produces an osteonecrosis of the tumoral bed which is 1 or 2mm deep, reducing the rate of recurrence to 2–4%.5 In spite of these positive results, the high risk of fracture due to difficult control of the depth of the induced osteonecrosis prevents this procedure from becoming the method of choice.6 The osteonecrosis produced by phenol is limited to a depth of 1.5mm, reducing the risk of fracture but presenting a rate of recurrence of 20–30%.6,7 The effectiveness of phenol is increased when used together with cement after curettage, with a rate of recurrence which varies between 3% and 17%.7 Nevertheless, some studies have reported a high recurrence among grade iii GCTB.7 Block resection and subsequent reconstruction of these cases near the joints has been described as the treatment of choice due its low rate of local recurrence compared to curettage,3,8 whilst other authors argue that this option is not adequate for the majority of cases.7,9 We believe that this option is very aggressive, more so considering the young age of patients in the series, so we opted for block resection and reconstruction in cases of Campanacci grade iii GCTB3 with significant cortical destruction.

The literature contains reports from series with different treatments which obtained similar results and with a comparable rate of recurrences (Table 2).1,3,7,8,10–22 GCTB presents an overall rate of recurrence of 20% in block resections, increasing to 50% with intralesional curettage.3,23 Our series presented a rate of first recurrence of 25.8%, a result comparable with that of the relevant series of Campannaci,3 who obtained a rate of recurrence of 27%. High-speed drilling and adjuvants such as cryotherapy with liquid nitrogen and radiotherapy have been used to decrease the rate of recurrence. Likewise, the use of substances such as phenols, corticoids, polymethylmethacrylate cement, zoledronic acid, aqueous zinc hydrochloride and hydroxyapatite has also been studied.5,7–9,11

Rate of recurrence reported in the literature following intralesional treatment for giant cell tumor of bone.

| Author and reference | Year | Follow-up | Patients | Adjuvant used | Recurrence (%) |

| Goldenberg et al.13 | 1970 | 9.9 years | 91 | Bone graft | 24.18 |

| Dahlin et al.14 | 1970 | 10 years | 37 | Cytotoxic | 41 |

| Larsson et al.15 | 1975 | 10 years | 53 | None or bone graft | 47 |

| Marcove et al.12 | 1978 | 2 years | 52 | Cryosurgery | 23 |

| Sung et al.1 | 1982 | 2 years | 34 | Phenol | 41.2 |

| McDonald et al.8 | 1986 | 7 years | 85 | Phenol | 34 |

| Campanacci et al.3 | 1987 | 10 years | 151 | None | 27 |

| Waldram et al.16 | 1990 | 6 years | 20 | None | 35 |

| O’Donnell et al.25 | 1994 | 4 years | 60 | Cement | 25 |

| Blackley et al.17 | 1999 | 6 years | 59 | Drilling | 12 |

| Boons et al.18 | 2002 | 7 years | 36 | Polymethylmethacrylate+liquid nitrogen | 30 |

| Zhen et al.11 | 2004 | 11 years | 92 | Aqueous zinc hydrochloride | 13 |

| Kivioja et al.19 | 2008 | 5 years | 294 | Bone, cement | 19 |

| Balke et al.20 | 2008 | 5 years | 214 | Polymethylmethacrylate | 16.6 |

| Nishisho et al.22 | 2011 | 2.5 years | 1 | Zoledronic acid | None |

| Fraquet et al.21 | 2009 | 2 years | 30 | Cement | 30 |

| Errani et al.10 | 2010 | 3 years | 64 | Phenol, alcohol, cement | 12.5 |

| Our series | 2013 | 12 years | 97 | Drilling+bone graft or block resection | 25.8 |

Although GCTB is considered as a benign bone tumor, some publications have shown that about 10% of these tumors become malignant.8,23,24 Our series presented a rate of malignization of 8.2%.

The study presented certain limitations, such as being a single-center study, with a single therapeutic protocol. Despite being a limitation, the protocol used was similar to those in other works published in the literature. Another weakness of the study was being a retrospective study of a series of cases presenting different locations. The grade iii GCTB group was reduced, but comparable with the series consulted. In spite of this, we consider the size of the sample in our study and its long follow-up period as sufficient strengths to balance the limitations.

ConclusionWe consider curettage with high-speed drilling and bone graft in Campanacci grade i and ii GCTB, as well as block resection and subsequent reconstruction in grade iii cases, or in grade ii when curettage is not technically feasible, as the treatment of choice.

Level of evidenceLevel of evidence iv.

Ethical responsibilitiesProtection of people and animalsThe authors declare that this investigation did not require experiments on humans or animals.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their workplace on the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that this work does not reflect any patient data.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Please cite this article as: Abat F, Almenara M, Peiró A, Trullols L, Bagué S, Grácia I. Tumor de células gigantes óseo. Noventa y siete casos con seguimiento medio de 12 años. Rev Esp Cir Ortop Traumatol. 2015;59:59–65.