Sciatic nerve injuries associated with acetabular fractures can be post-traumatic, perioperative or postoperative. Late postoperative injury is very uncommon and can be due to heterotopic ossifications, muscular scarring, or implant migration. A case is presented of a patient with a previous transverse acetabular fracture treated with a reconstruction plate for the posterior column. After 17 years, she presented with progressive pain and motor deficit in the sciatic territory. Radiological and neurophysiological assessments were performed and the patient underwent surgical decompression of the sciatic nerve. A transection of the nerve was observed that was due to extended compression of one of the screws. At 4 years postoperatively, her pain had substantially diminished and the paresthesias in her leg had resolved. However, her motor symptoms did not improve. This case report could be relevant due to this uncommon delayed sciatic nerve injury due to prolonged hardware impingement.

Las lesiones del nervio ciático asociadas a fracturas acetabulares pueden ser postraumáticas, perioperatorias o postoperatorias. Las lesiones postoperatorias tardías son extremadamente raras y pueden deberse a osificaciones heterotópicas, cicatrización hipertrófica o migración del material de osteosíntesis. Presentamos el caso de una paciente de 39 años con antecedente de una fractura transversa de acetábulo izquierdo intervenida mediante placa de reconstrucción en la columna posterior. Tras 17 años asintomática, comenzó con dolor progresivo y paresia de varios meses de evolución en territorio ciático. Tras el pertinente estudio neurofisiológico y radiológico, se decidió intervenir quirúrgicamente a la paciente, constatándose una transección del nervio ciático por compresión prolongada de uno de los tornillos de la placa de osteosíntesis. A los 4 años tras la descompresión quirúrgica, la paciente presentaba mejoría significativa del dolor neurógeno, sin parestesias. No obstante, no ha experimentado recuperación motora. Este caso clínico suscita interés dada la excepcionalidad de esta presentación tardía de lesión nerviosa, producida por la compresión prolongada del material de osteosíntesis.

Lesions of the sciatic nerve associated with acetabular fractures may occur during the causal trauma, iatrogenically during surgery or as a late complication. Figures of up to 30%1 have been given for the incidence of post-traumatic injury to this nerve in cases of hip luxation and fracture-luxation, and it occurs the most frequently in fractures of the wall or rear column. Excessive retraction and the positioning of separators or screws close to the greater or lesser sciatic foramen.2 Postoperative lesions are rare and may be due to several factors. Soon after surgery a haematoma may cause compression neuropathy.3 Later, muscle or capsular scarring, the migration of osteosynthesis material and heterotopic ossification have been said to be causes of this.1,4,5

We present a clinical case of a patient with a postoperative lesion of the sciatic nerve caused by prolonged compression by the reconstruction plate which caused intraneural dissection 17 years after the osteosynthesis of an acetabular fracture.

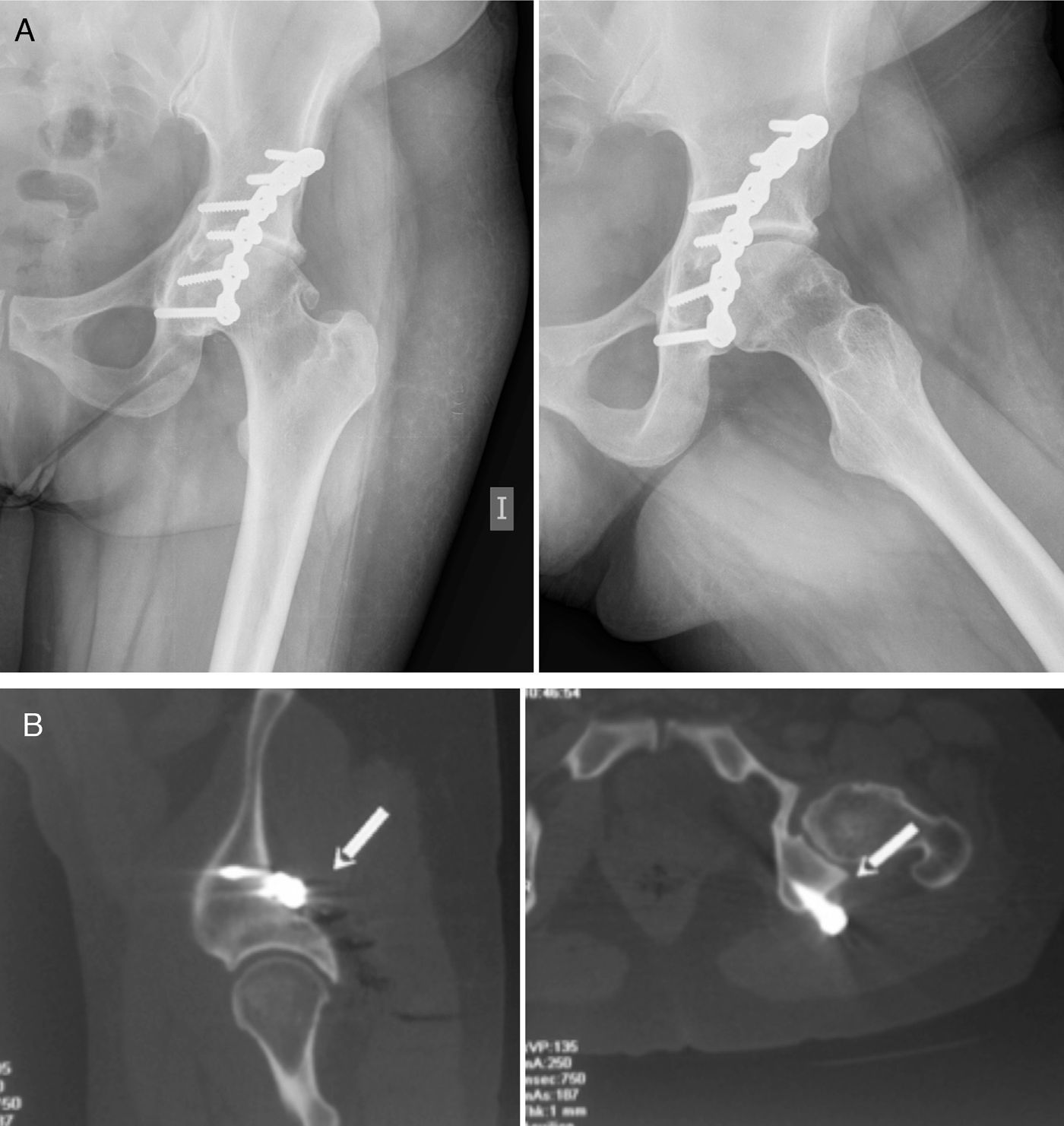

Clinical caseA 39-year-old patient with a history of upper transverse fracture of the left acetabulum in a traffic accident in 1991. Surgical treatment involved osteosynthesis of the rear column with a reconstruction plate. No neurovascular alterations arose and the postoperative period passed without incident. In the year 2008, 17 years after the initial injury, the patient visited due to gradually increasing gluteal pain irradiating to the rear face of the right leg, with paresthesias of the said area that had evolved over several months. There was no groin pain and the range of hip movement was painless and functional, with 110° of flexion, complete extension, 15° of internal rotation and 30° of external rotation. The gluteal pain increased with prolonged sitting and flexion, adduction and internal rotation of the hip (FAIR test).6 There was motor function deficit with paresis of the toe and peroneal muscle extensors (M4/5), as well as those of the calf muscles (M3/5) in the same leg. Examination of the spinal column was anodyne, while Lasegue's sign was positive with painful palpation in the gluteal region. Simple X-ray showed the osteosynthesis plate with no signs of loosening in comparison with previous examinations, and there were signs of degeneration in the coxofemoral joint (Fig. 1a). The initial diagnosis of suspicion was of a piriformis syndrome, possibly due to post-surgical fibrosis. The electrophysical study revealed proximal involvement of the left sciatic nerve that was greater in the case of the fibres pertaining to the internal poplitheal nerve. This gave rise to a moderate loss of motor units in the gastrocnemius muscle, with signs of active denervation. During subsequent months the pain gradually worsened in the rear of the leg, so the electrophysiological examination was repeated. A moderate chronic neurogenic pattern was observed in the muscles controlled by the external and internal poplitheal sciatic nerves, of which the latter were the most affected. Greater Wallerian degeneration of the sensorial component was detected, and these findings were interpreted as progression or a return to an acute state of the nerve lesion in a known chronic condition. Magnetic nuclear resonance was used to try to identify the cause of the nerve compression, and this revealed piriformis muscle atrophy and fat infiltration, although the sciatic nerve could not be suitably evaluated due to the proximity of the osteosynthetic artefact material. Computerised axial tomography (CAT) detected the protrusion of the head of one of the osteosynthesis screws into the path of the sciatic nerve close to the piriformis muscle (Fig. 1b).

The patient experienced gradual worsening of the pain and paresthesias in the leg which were not suitably controlled by analgesics and physiotherapy. It was therefore decided to operate surgically to extract the osteosynthesis material and decompress the sciatic nerve.

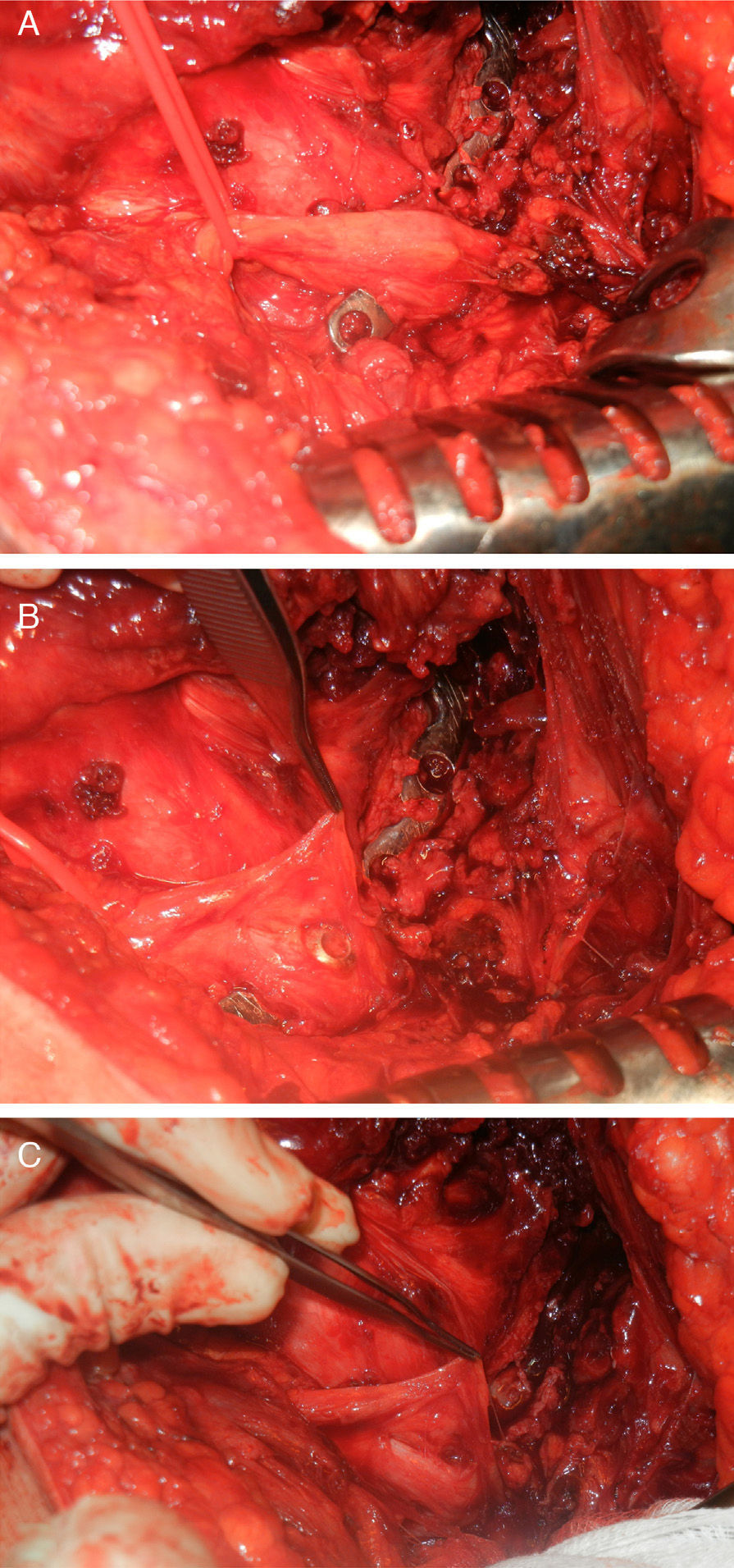

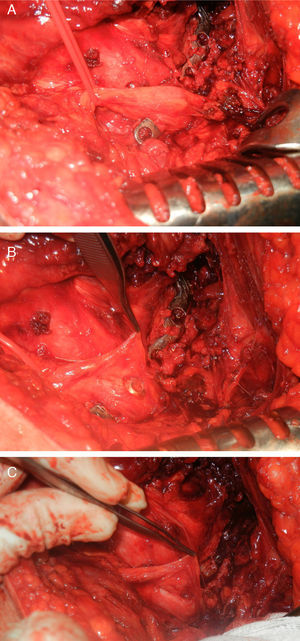

The Kocher-Langenbeck hip approach was used, with the patient in lateral decubitus, and magnifying spectacles were used. To relieve the pressure on the sciatic nerve a suitable position with hip extension and knee flexion was adopted. After making the incision over the fasciae latae, the femoral insertion of the greater gluteal tendon was partially freed to obtain suitable retraction of the rear flap. The sciatic nerve was identified from a more distal zone of the approach, following the fibres of the femoral quadratus muscle up to the more rearward zone. The dissection was then continued longitudinally and more proximally, cutting the piriformis tendon and the short external rotators. A diffuse thickening appeared in the route of the nerve over the plate (Fig. 2a). At this point it was found that the head of one of the screws had caused transection of the nerve due to a probable mechanism of prolonged compression (Fig. 2b). When the nerve was freed it was possible to identify a longitudinal buttonhole-shaped defect in the same due to compression by one of the screws (Fig. 2c), which showed signs of loosening. The dissection was completed from the insertion of the greater gluteus in the femur up to the proximal greater sciatic foramen, and the sciatic nerve was checked to ensure that it could be suitably moved. Macroscopic identification of the reason for the greater motor involvement of the tibial division of the sciatic nerve was not possible, given that the screw seemed to be located between the tibial and peroneal divisions of the sciatic nerve. Prophylaxis commenced after surgery against heterotopic ossifications, using indometacin (25mg every 8h) during 4 weeks. There were no incidents worthy of mention immediately after the operation, and the patient experienced symptomatic relief from the first, with gradual improvement over the following weeks.

Intraoperative images. (A) Identification of the sciatic nerve over the osteosynthesis plate, showing thickening of the nerve in the zone. (B) Initial dissection showing the protrusion of one of the osteosynthesis screws. (C) The final situation following removal of the plate in which the presence of a buttonhole in the cross-section of the sciatic nerve stands out.

After 4 years the neurogenic pain in the leg has improved considerably, with only occasionally discomfort after prolonged sitting. Sensory examination is normal. Nevertheless, the patient has not experienced any motor recovery whatsoever. Brooks’ functional scale was used, in which different items are grouped into 7 categories: walking, standing, pain, phantom limb pain, paresthesias, overall quality of life and overall functional result.7 On this scale the patient was found to be able to walk without restriction or the need for orthesis or walking aids, with a high level of satisfaction (8 out of 10). However, the patient mentioned difficulty in walking on very inclined surfaces or when quickly climbing stairs. She could remain standing satisfactorily (8/10) for more than 30min. The patient mentioned occasional slight pain in the rear leg (2/10), with mild sporadic paresthesias (2/10) in the rear leg and sole of the foot. The overall functional result was satisfactory, with a score of 8 out of 10, while overall quality of life scored 7 out of 10. No other therapeutic options have been considered to try to recover motor function, given that the patient is highly satisfied with the result obtained and performs her everyday activities without any restrictions.

DiscussionThe appropriate treatment of these sciatic nerve lesions associated with acetabular fractures starts with suitable anamnesis to establish a temporal relationship between the onset of symptoms and the causal trauma or surgical operation. A detailed physical examination including evaluation of sensitivity and motor function is primordial to make it possible to locate the level of the injury. Imaging studies include simple X-rays, CAT and nuclear magnetic resonance, which make it possible to identify heterotopic ossifications, the movement of osteosynthesis material, muscular hypotrophy and postoperative fibrosis. It is important to establish a differential diagnosis vs. Myelopathy, lumbar radiculopathy and other causes of neurogenic pain. Electromyography may help to locate the location of the lesion and establish whether it is neuroapraxia, axonotmesis or neurotmesis.

Several manoeuvres have been described to minimise iatrogenic injuries to the sciatic nerve during osteosynthesis of an acetabular wall or rear column fracture. During an approach from the rear it is recommendable to place the hip in extension and the knee in flexion to reduce traction of the nerve, avoiding forceful separation while also positioning separators in the lesser sciatic foramen.2,8 Intraoperative neurophysiology, especially evoked somatosensorial potentials together with EMG, is useful in the prevention of iatrogenic injuries thanks to its instantaneous monitoring. In this way the surgical team is able to identify the possible causes of neurological lesions in real time. The heterotopic ossifications which may occur after an acetabular fracture are a potential cause of restricted hip mobility, and they may also give rise to sciatic nerve compression. It is therefore recommendable to use pharmacological prophylaxis against these ossifications (indometacin or non-steroid anti-inflammatory drugs), together with physiotherapy and early mobilisation and postoperative radiotherapy, especially if an expanded approach is used.

Few works have described the freeing of the sciatic nerve following acetabular fractures.4,5,9,10 Stiehl and Stewart published a case of sciatic neuropathy following the loosening of an osteosynthesis plate 6 months after the initial operation. Similarly to our case, these authors detected the compression of the nerve by one of the screws. After the osteosynthesis material was removed the patient's symptoms improved, although paresthesias in the foot continued.4 Thakkar and Porter published another case of a patient with post-traumatic laceration of the sciatic nerve after rear hip fracture-luxation. Neurorraphy was performed and after one year the lesion had evolved well, although with hypoesthesias in dermatomes L4 and L5 and slight paresis (M4/5) in the hamstring muscles. The patient suffered a fall 3 years after the initial lesion, and debuted with gradually increasing pain, paresthesias in the medial face of the leg and a motor deficit with steppage, secondary to entrapment of the sciatic nerve by heterotopic bone. After removal of the ossification and freeing of the nerve the patient experienced an improvement in the pain and paresthesias, although the previously existing motor deficit did not improve.5

In a retrospective revision of the freeing of the sciatic nerve in cases of neuropathy associated with acetabular fractures, it was found that all of the patients treated improved partially or completely in terms of pain and sensory symptoms. 57% of the patients who had some motor deficit showed a functional improvement, although only 40% of those with severe paresis (steppage) improved. The authors of this work concluded that while surgical decompression may resolve sensory symptoms, motor recovery is less probable.10

This clinical case aroused interest due to the exceptional nature of this late presentation of a nerve lesion, caused by prolonged compression by osteosynthesis material. This rare cause of neurological compromise should be considered in patients with a history of acetabular fracture. In the case we present, decompression of the sciatic nerve gave good results in terms of the symptoms of pain and sensory deficit, although no improvement in motor function was detected.

Level of evidenceLevel of evidence IV.

Ethical responsibilitiesProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments took place using human beings or animals for this research.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they followed the protocols of their centre of work governing the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors obtained the informed consent of the patients and/or subjects referred to in this article. This document is in the hands of the corresponding author.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Please cite this article as: Moreta J, Foruria X, Labayru F. Presentación tardía de lesión del nervio ciático secundaria a compresión por placa de osteosíntesis acetabular. Rev Esp Cir Ortop Traumatol. 2016;60:251–255.