The implementation of National Prostheses Registries allows us to obtain a large amount of data and make conclusions in order to improve the use of them. Sweden was the first country to implement a National Prostheses Registry in 1979. Catalonia has been doing this since 2005. The aim of our study is to analyse the evidence that supports primary total hip replacement in Catalonia in the last 9 years, based on the Arthroplasty Registry of Catalonia (RACat).

Material and methodsA review of the literature was carried out of the prosthesis (acetabular cups/stems) reported in the RACat between the period 2005 to 2013 in the following databases: ODEP (Orthopaedic Data Evaluation Panel), TRIP database, PubMed, and Google Scholar. Those prostheses implanted in less than 10 units (182 acetabular components corresponding to 49 models/228 stems corresponding to 63 models) were excluded.

ResultsA total of 18,634 (99%) implanted acetabular cups were analysed out of a total number of 18,816, corresponding to 74 different models. In 18 models (2527 acetabular cups) no clinical evidence to support its use was found. An analysis was performed on 19,367 (98.84%) out of a total number of 19,595 implanted stems, corresponding to 75 different models. In 16 models (1845 stems) no clinical evidence was found to support their use. Variable evidence was found in the 56 models of acetabular cups (16,107) and 59 models of stems (17,522), most of it corresponding to level iv clinical evidence.

ConclusionsThere was a significant number implanted prostheses evaluated (13.56% acetabular cups/9.5% stems) for which no clinical evidence was found. The elevated number of models is highlighted (49 types for acetabular cups/63 types for stems) with less than 10 units implanted, which corresponds to only 1% of the total implants. The use of arthroplasty registers is shown to be an extremely helpful tool that allows analyses and conclusions to be made for the follow-up and post-marketing surveillance period.

La cumplimentación de registros sobre la implantación de prótesis permite obtener una gran cantidad de datos y extraer conclusiones que redundan en la mejora de la utilización de las mismas. Suecia fue el primer país en implantar un sistema de registro de artroplastias en 1979. Cataluña lo viene haciendo desde el año 2005. El objetivo de nuestro trabajo es analizar la evidencia que respalda a las prótesis implantadas en artroplastias totales de cadera primarias en Cataluña en los últimos 9 años sobre la base del Registro de Artroplastias de Cataluña (RACat).

Material y métodosSe realizó una revisión en la literatura de las prótesis (cotilos/vástagos) registrados en el RACat entre los años 2005-2013 en las siguientes bases datos: Orthopaedic Data Evaluation Panel (ODEP), Tripdatabase, Pubmed, Google académico. Se excluyeron aquellas prótesis implantadas en número inferior a 10 unidades (182 cotilos correspondientes a 49 modelos/228 vástagos correspondientes a 63 modelos).

ResultadosDe los 18.816 cotilos implantados, se analizaron 18.634 (el 99%), correspondientes a 74 modelos diferentes. En 18 modelos (2.527 cotilos) no se encontraron evidencias clínicas que respalden su uso. De los 19.595 vástagos implantados se analizaron 19.367 (el 98,84%), correspondientes a 75 modelos diferentes. En 16 modelos (1.845 vástagos) no se encontraron evidencias clínicas que respalden su uso. En los 56 modelos de cotilos (16.107) y los 59 modelos de vástagos (17.522) restantes las evidencias variaron en función del número de pacientes y los años de seguimiento, predominando los estudios con nivel de evidencia iv.

ConclusionesExiste un número significativo de prótesis implantadas evaluadas (13,56% cotilos/9,5% vástagos) en los que no se han encontrado evidencias clínicas. Cabe destacar el alto número de modelos (49 tipos para cotilos/63 tipos para vástagos) con una implantación inferior a 10 unidades que corresponden únicamente al 1% del total. La implantación de registros de artroplastias se revela como una herramienta extremadamente útil al permitirnos analizar y extraer conclusiones para la evaluación y el seguimiento poscomercialización.

Scientific associations have been responsible for the introduction of prostheses registries which provide follow-up and evaluation of the different existing models of prostheses. The patient's quality of life is improved by joint replacements and arthroplasty registries optimise orthopaedic treatment and improve scientific knowledge concerning the use of information on the outcome of this type of surgery. Sweden was the first country to introduce an arthroplasty registry system in 1979.1 Since then, different implant registry models have been implemented,2–5 which has led to an improvement in healthcare quality and a higher level of transparency in the use of prostheses.

In Spain, a ministerial order was published in the Official State Bulletin (Order SCO/3603/2003 of 18th December) to create National Implant Registries, and although they are not yet available, the Spanish Society of hip Surgery (SECCA), together with the Spanish Orthopaedic and Traumatology Society (SECOT), and the Spanish Agency for Medications and Healthcare Products (AEMPS), are working towards the creation of this tool.6,7 In March 2005, Catalonia established the Catalonian Arthroplasty Register (RACat). This registry principally collects the activity carried out in hospitals belonging to the Catalonian public health system and contains information relating to patients, interventions and outcome from prostheses used. Initially, due to practical reasons, only knee and hip prostheses were included, which are those most frequently implanted.8,9

In today's context of continuous technological innovations and advances, the number of implants available is increasingly greater. It is therefore pertinent to have evidence-based practice information on the different models, so that clinical practice may thus be supported by it.

In addition to the introduction of an Arthroplasty Registry, countries such as United Kingdom have developed complementary bodies such as the Orthopaedic Data Evaluation Panel (ODEP),10 which is dependent upon its National Health System and which serves as a reference for evaluating data in the follow-up of different primary prostheses, of both hip and knee, many of which have also been implanted in our country. Their functioning is based on the request from manufacturers of prostheses, of information regarding clinical evidence of the implants they manufacture, to which is added the follow-up in years of implantation within the National Arthroplasty Registry. The prostheses are therefore classified by the number of years following implantation (3, 5, 7 or 10) and by the quality of clinical evidence supported (level A: strong evidence, level B: reasonable evidence and level C: weak evidence); 10A would be the highest possible classification. To obtain said classification, the prostheses have to have a 10% or below10% failure rate after 10 years of usage, a cohort study with over 500 cases at the start and a survival rate after 10 years of 90% calculated with the Kaplan–Meier method. Those products which were registered, and which have been implanted less than 3 years, are classified as “pre-entry”. The majority of them present on-going studies. The prostheses which the manufacturers have no evidence of do not appear in this data base and their number is unknown.

We were able to find recent studies in the literature which use the National Arthroplasty Registry of the United Kingdom, the ODEPplatform, and other data bases to show the level of evidence of all prostheses implanted in that country.11 With the use of RACat as our base, we set out to analyse the evidence supporting the use of primary total hip replacements in hospitals in Catalonia.

Material and methodsInformation sourceFrom the information available in the RACat12 all cup and stem models implanted in total hip replacements carried out in Catalonia between 2005 and 2013 were identified. Only the primary total hip replacements, either cemented or cementless from within the RACat registry were selected, with exclusion of revision implants and those used for “resurfacing”. We also excluded those implants were which used in units of 10 or under throughout the study period, since such a low number was considered to be insignificant.

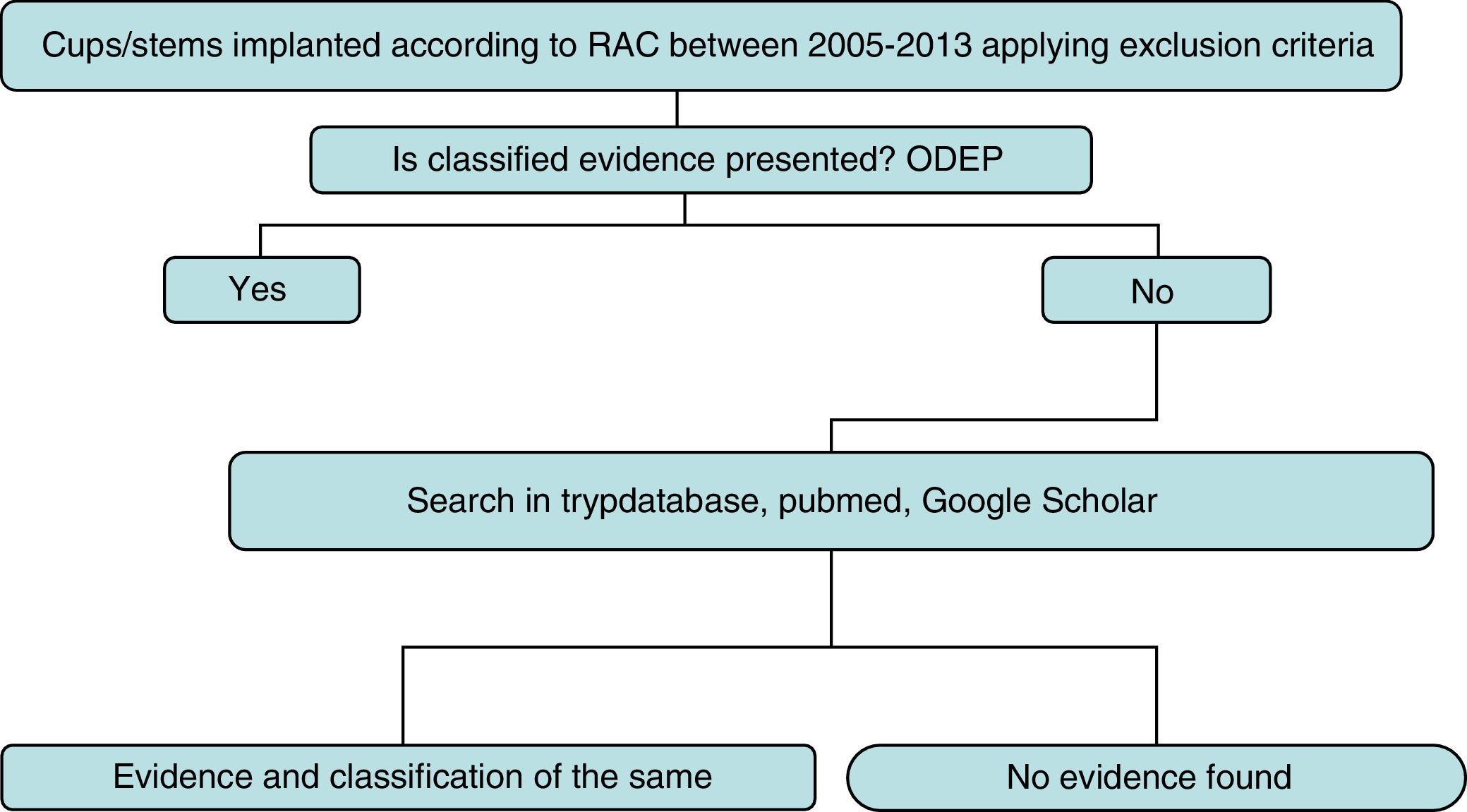

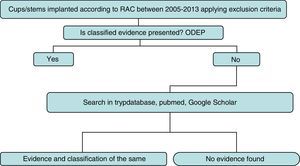

Strategy and searchThe detailed search strategy in Fig. 1 was followed. Initially, the ODEP platform was used to identify the models with classified evidence. For identified models the level of evidence was reported by following said classification, based on the number of years following implantation and the quality of the supported clinical evidence. For non classified models or non recorded models within the ODEP a review of studies published in the literature (national and international) was made in the Trypdatabase, Pubmed and Google Scholar databases.

Search terms and strategy were “name of the prosthesis” and “hip”. The “name of the prosthesis” used is the trade name which appears in the RACat, and this is verified in the official manufacturer's web site. If discrepancies occurred, we used the 2 names to carry out the search.

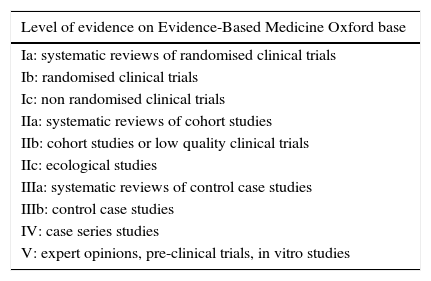

Titles and summaries of articles found were reviewed, and those potentially relevant were selected. We defined evidence as those publications which assessed the clinical effectiveness of a certain implant. We excluded those studies on animals and those carried out in vitro or using laboratory experiments. We later assigned a level of evidence to the articles found on the basis of the classification of the Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine Oxford13 as detailed in Table 1.

Levels of evidence according to Oxford scale.

| Level of evidence on Evidence-Based Medicine Oxford base |

|---|

| Ia: systematic reviews of randomised clinical trials |

| Ib: randomised clinical trials |

| Ic: non randomised clinical trials |

| IIa: systematic reviews of cohort studies |

| IIb: cohort studies or low quality clinical trials |

| IIc: ecological studies |

| IIIa: systematic reviews of control case studies |

| IIIb: control case studies |

| IV: case series studies |

| V: expert opinions, pre-clinical trials, in vitro studies |

Two researchers independently made the search and the critical reading of the literature for both the cups and stems, and later combined the data.

Strategy of analysisLastly, those implants with a higher level of evidence were analysed and those where no clinical evidence was found in the data bases used. Descriptive analysis was made using the tables of frequency and percentages. All analysis was made with the Office Excel 2015 package.

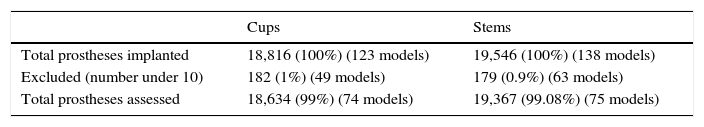

ResultsBetween 2005 and 2013 the RACat was notified of the implantation of 18,816 cups. By applying the previously mentioned exclusion criteria 18,634 (99%) were analysed, which corresponded to 74 different models; 49 models (182 cups) were implanted in a number equal to or lower than 10 units, corresponding to 1% of totals implants.

During the same period the RACat was notified of the implantation of 19,546 stems. By applying the previously mentioned exclusion criteria 19,367 (99.08%), were analysed, corresponding to 75 different models. 63 models (179 stems) were implanted in a number equal to or lower than 10 units, corresponding to 0.9% of the total (Table 2).

Total sample of prostheses implanted and assessed.

| Cups | Stems | |

|---|---|---|

| Total prostheses implanted | 18,816 (100%) (123 models) | 19,546 (100%) (138 models) |

| Excluded (number under 10) | 182 (1%) (49 models) | 179 (0.9%) (63 models) |

| Total prostheses assessed | 18,634 (99%) (74 models) | 19,367 (99.08%) (75 models) |

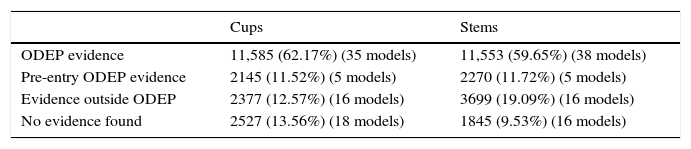

In 18 models (2527 cups), 13.56%, there was no clinical evidence in the data bases used. In the remaining 56 models, (16,023 cups) evidence varied according to the number of patients and the years of follow-up, with evidence level IV studies predominating.

In 16 models (1845 stems), 9.53%, no clinical evidence was found in the data bases used. In the remaining 59 models (17,522 stems) evidence varied according to the number of patients and follow-up years, with evidence level IV studies predominating (Tables 3–7)

Percentage of implants with evidence.

| Cups | Stems | |

|---|---|---|

| ODEP evidence | 11,585 (62.17%) (35 models) | 11,553 (59.65%) (38 models) |

| Pre-entry ODEP evidence | 2145 (11.52%) (5 models) | 2270 (11.72%) (5 models) |

| Evidence outside ODEP | 2377 (12.57%) (16 models) | 3699 (19.09%) (16 models) |

| No evidence found | 2527 (13.56%) (18 models) | 1845 (9.53%) (16 models) |

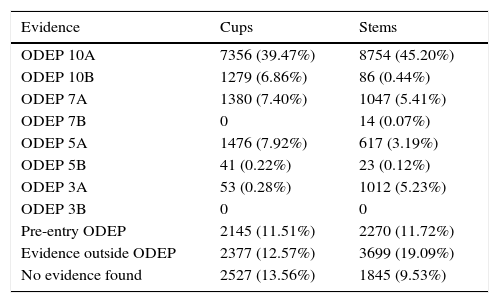

Classification of evidence.

| Evidence | Cups | Stems |

|---|---|---|

| ODEP 10A | 7356 (39.47%) | 8754 (45.20%) |

| ODEP 10B | 1279 (6.86%) | 86 (0.44%) |

| ODEP 7A | 1380 (7.40%) | 1047 (5.41%) |

| ODEP 7B | 0 | 14 (0.07%) |

| ODEP 5A | 1476 (7.92%) | 617 (3.19%) |

| ODEP 5B | 41 (0.22%) | 23 (0.12%) |

| ODEP 3A | 53 (0.28%) | 1012 (5.23%) |

| ODEP 3B | 0 | 0 |

| Pre-entry ODEP | 2145 (11.51%) | 2270 (11.72%) |

| Evidence outside ODEP | 2377 (12.57%) | 3699 (19.09%) |

| No evidence found | 2527 (13.56%) | 1845 (9.53%) |

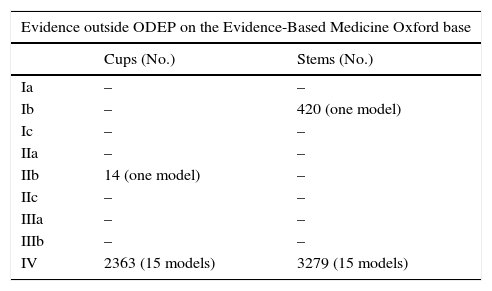

Level of evidence of unclassified implants in the ODEP registry on the Oxford classification base.

| Evidence outside ODEP on the Evidence-Based Medicine Oxford base | ||

|---|---|---|

| Cups (No.) | Stems (No.) | |

| Ia | – | – |

| Ib | – | 420 (one model) |

| Ic | – | – |

| IIa | – | – |

| IIb | 14 (one model) | – |

| IIc | – | – |

| IIIa | – | – |

| IIIb | – | – |

| IV | 2363 (15 models) | 3279 (15 models) |

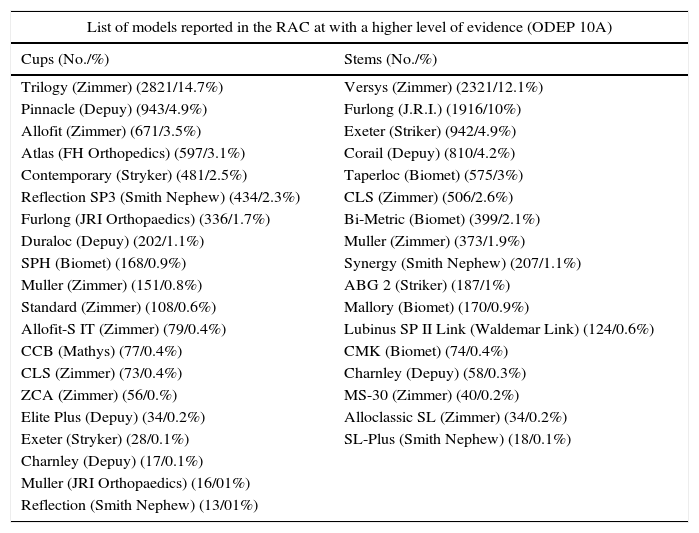

List of models reported in the RACat with a higher level of evidence (ODEP 10A) in total numbers and percentages.

| List of models reported in the RAC at with a higher level of evidence (ODEP 10A) | |

|---|---|

| Cups (No./%) | Stems (No./%) |

| Trilogy (Zimmer) (2821/14.7%) | Versys (Zimmer) (2321/12.1%) |

| Pinnacle (Depuy) (943/4.9%) | Furlong (J.R.I.) (1916/10%) |

| Allofit (Zimmer) (671/3.5%) | Exeter (Striker) (942/4.9%) |

| Atlas (FH Orthopedics) (597/3.1%) | Corail (Depuy) (810/4.2%) |

| Contemporary (Stryker) (481/2.5%) | Taperloc (Biomet) (575/3%) |

| Reflection SP3 (Smith Nephew) (434/2.3%) | CLS (Zimmer) (506/2.6%) |

| Furlong (JRI Orthopaedics) (336/1.7%) | Bi-Metric (Biomet) (399/2.1%) |

| Duraloc (Depuy) (202/1.1%) | Muller (Zimmer) (373/1.9%) |

| SPH (Biomet) (168/0.9%) | Synergy (Smith Nephew) (207/1.1%) |

| Muller (Zimmer) (151/0.8%) | ABG 2 (Striker) (187/1%) |

| Standard (Zimmer) (108/0.6%) | Mallory (Biomet) (170/0.9%) |

| Allofit-S IT (Zimmer) (79/0.4%) | Lubinus SP II Link (Waldemar Link) (124/0.6%) |

| CCB (Mathys) (77/0.4%) | CMK (Biomet) (74/0.4%) |

| CLS (Zimmer) (73/0.4%) | Charnley (Depuy) (58/0.3%) |

| ZCA (Zimmer) (56/0.%) | MS-30 (Zimmer) (40/0.2%) |

| Elite Plus (Depuy) (34/0.2%) | Alloclassic SL (Zimmer) (34/0.2%) |

| Exeter (Stryker) (28/0.1%) | SL-Plus (Smith Nephew) (18/0.1%) |

| Charnley (Depuy) (17/0.1%) | |

| Muller (JRI Orthopaedics) (16/01%) | |

| Reflection (Smith Nephew) (13/01%) | |

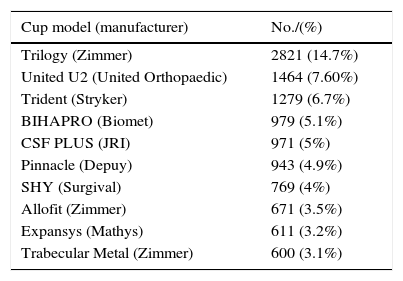

List of the 10 models of cups and stems most implanted in Catalonia, according to the data reported in the RACat.

| Cup model (manufacturer) | No./(%) |

|---|---|

| Trilogy (Zimmer) | 2821 (14.7%) |

| United U2 (United Orthopaedic) | 1464 (7.60%) |

| Trident (Stryker) | 1279 (6.7%) |

| BIHAPRO (Biomet) | 979 (5.1%) |

| CSF PLUS (JRI) | 971 (5%) |

| Pinnacle (Depuy) | 943 (4.9%) |

| SHY (Surgival) | 769 (4%) |

| Allofit (Zimmer) | 671 (3.5%) |

| Expansys (Mathys) | 611 (3.2%) |

| Trabecular Metal (Zimmer) | 600 (3.1%) |

| Stem model (manufacturer) | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Versys (Zimmer) | 2321 (12.1%) |

| United U2 (United Orthopaedic Corporation) | 2013 (10.5%) |

| Furlong (J.R.I.) | 1916 (10.0%) |

| Karey (Surgival) | 1252 (6.5) |

| Exeter (Stryker) | 942 (4.9%) |

| Corail (Depuy) | 810 (4.2%) |

| CBH (Mathys) | 601 (3.1%) |

| Taperloc (Biomet) | 575 (3.0%) |

| Shine-C (Surgival) | 528 (2.7%) |

| CLS (Zimmer) | 506 (2.6%) |

The ODEP data bases is a useful tool which may help specialists in Orthopaedic and Trauma surgery make a fast and simplified comparison of the multitude of prostheses, with regards to their viability and efficacy from clinical criteria. However, according to our findings, only 62.17% of cups and 59.65% of stems implanted in Catalonia, according to the data notified in the RACat during the period of study, were classified on this data base. We therefore believe that review is justified if we are to gain an overall idea of the evidence supporting the different models implanted.

It should be noted that studies found which were not included in the ODEP data bases mainly presented poor evidence (level IV), with low sample sizes and short follow-up periods.

According to our review, no clinical evidence was found to support usage in 13.56% of cups and 9.53% of stems of primary hip prostheses implanted in Catalonia between 2005 and 2013. Although our search of references is extensive, we have to bear in mind that non-indexed literature in the data bases was used and the fact that unidentified literature may therefore exist in our search. Poolman et al.,14 for example, collated the models implanted in Holland, observing that 25% of them were not found in the ODEP data base but could be found in other more local data bases.

Another element to underline is whether the implant in question should appear with its trade name in the different articles, with the possibility of studies on specific implants which only refer to their generic name – for example “cementless cup” – and thus not being located in our search. For this reason, and to avoid this problematic situation, we believe it is essential to explicitly indicate the prosthesis model used in each work so that other surgeons may find it easier to take decisions regarding the use of one or another type of implant. Similarly, we have found that several mistakes have been made between the names of the arthroplasty models within the RACat, since certain names do not tally with the manufacturer's names on their official web page, leading to duplication within the arthroplasty registry. We therefore believe it essential that the exact transcription be made by the surgeon of the manufacturer's name to the RACat to avoid errors and promote the correct functioning of this useful tool.

Another limitation would be that evidence which is being used has not yet been published or is in preliminary stages with as of yet inconclusive outcome. A language bias should equally be taken into consideration, since the literature reviewed had summaries in English.

The previously cited limitations restrict us and our findings must therefore be interpreted. The list of implants in which we have found evidence therefore does not involve said evidence in other data bases outside those consulted in our work.

The large number of implants in which no clinical evidence was found is of concern and needs highlighting (13.56% cups/9.53% stems). This should encourage the orthopaedic surgeons to use those implants which present the best possible evidence. We therefore highlight in our work those implants with the best level of evidence and which have demonstrated the best parameters in safety, reliability and clinical efficacy.

On the one hand we wish to underline the valuable information provided by the RACat without which this work would not have been possible, and, on the other, the importance of the introduction of National Arthoplasty Registries which will lead to post-implant controls, evaluations and analysis similar to this one.

ConclusionsDespite the fact the majority of prostheses used current clinical studies to support their usage, there is a significant number of cups (13.56%)and stems (9.53%) implanted in Catalonia between 2005 and 2013 in which clinical evidence was not found that support them. It is worth noting the high number of models, 49 cup models and 63 stem models, with implantation under or equal to 10 units in a period of 9 years, corresponding to only 1% of the total.

Level of evidenceIIa.

Ethical responsibilitiesProtection of people and animalsThe authors declare that for this research no experiments on human beings or animals have been conducted.

Data confidentialityThe authors declare they have adhered to the protocols of their centre of work on the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Please cite this article as: Chaverri-Fierro D, Lobo-Escolar L, Espallargues M, Martínez-Cruz O, Domingo L, Pons-Cabrafiga M. Artroplastias primarias de cadera implantadas en Cataluña: ¿qué evidencia clínica respalda a nuestras prótesis? Rev Esp Cir Ortop Traumatol. 2017;61:139–145.