Hip fractures in centenarians are rising due to the increase in life expectancy. The objective of this study is to compare the characteristics of centenarians’ hip fracture with a younger control group, and to analyze whether there are differences in terms of in-hospital mortality, complications, and short-medium-term survival between them.

Material and methodsRetrospective case–control study, with a series of 24 centenarians and 48 octogenarians with a hip fracture. Comorbidities and Charlson index, surgical delay, complications and mortality during admission, and hospital stay were analyzed. At discharge, early mortality, survival after one year, and return to previous functionality were assessed.

ResultsNo significant differences were found in baseline parameters or comorbidities (P > .05), and the type of was a woman with an extracapsular fracture. Hospital stay was longer in thecontrol group (p=.038), and the most frequent complication was anemia requiring transfusion (23/24 in centenarians, p<.0001). In-hospital mortality and accumulated at one year in the centenarians was 33 and 67%, respectively, compared to 10 and 25% in the octogenarians (p=.017, OR=4.3 [1,224–15,101] and p=.110). Only 2 centenarian patients were able to walk again after the intervention, while in the control group 53.84% returned to the previous functional situation (p=.003).

ConclusionsCompared to a control group of younger patients, in-hospital mortality and in the first year after a hip fracture is significantly higher in centenarians, and very few recover activity prior to the fracture.

La mejoría de la esperanza de vida está incrementando la incidencia de fractura de cadera en centenarios. Nuestro objetivo es comparar las características basales de una serie de centenarios con fractura de cadera frente a controles de menor edad, analizando si existen diferencias en cuanto a complicaciones, mortalidad intrahospitalaria y supervivencia a corto-medio plazo.

Material y métodosEstudio retrospectivo, tipo caso control, sobre 24 centenarios y 48 controles octogenarios con fractura de cadera. Se analizó la presencia de comorbilidades y el índice de Charlson, la demora quirúrgica, las complicaciones, la estancia hospitalaria y la mortalidad durante el ingreso. Al alta se valoró la mortalidad precoz, la supervivencia después del año y el retorno a la funcionalidad previa.

ResultadosNo se encontraron diferencias significativas en parámetros basales ni en comorbilidades (p > 0,05), siendo el paciente tipo una mujer con fractura extracapsular. La estancia hospitalaria fue mayor en el grupo control (p = 0,038) y la complicación más frecuente la anemia, que precisó transfusión sanguínea (23/24 en los centenarios, p < 0,0001). La mortalidad intrahospitalaria y acumulada al año en los centenarios fue del 33 y el 67%, respectivamente, frente al 10 y 25% en octogenarios (p = 0,017, OR = 4,3 [1,224-15,101] y p = 0,110]. Solo 2 pacientes centenarios consiguieron volver a caminar tras la intervención, frente a un 53,84% que volvió a la situación funcional previa en los controles (p = 0,003).

ConclusionesFrente a un grupo control de pacientes de menor edad, la mortalidad intrahospitalaria y en el primer año tras una fractura de cadera es significativamente mayor en los centenarios y muy pocos recuperan la actividad previa a la fractura.

Hip fracture in the elderly is an issue of enormous medical and social significance. Spain will be the world's most ageing country by 2050, with 40% of the population over 60 years of age.1 Increased life expectancy is increasing the number of centenarians in our setting, and it is expected that the number of hip fractures in this population group will grow to the same extent.2

Elderly patients have more comorbidities, and those over 85 years of age are up to 10 times more likely to suffer a hip fracture than those aged 65–69 years.3 The risk factors and predictors associated with high mortality have been studied for years,4 most notably gender, age, type of fracture, comorbidities, ASA, or a delay in surgery of more than 48h.5

There are very few studies that focus on a population group that is continually growing, i.e., patients over 100 years of age,6–15 and most are short case series. Advanced age is considered a risk factor related to increased mortality after hip fracture,16 and therefore the vital prognosis of hip fractures in centenarians would be expected to be very poor, due also to their comorbidities and frailty.

There is debate as to the best treatment for this type of patient, whether age and comorbidities influence prognosis, or whether they have reached this age perhaps because they have had fewer diseases.8,9 This is why we proposed a study to compare the characteristics of centenarian patients with a control group aged between 80 and 90 years, and to analyse whether there are differences in terms of complications and mortality, early and in the medium term.

Material and methodsWe conducted a retrospective, analytical, unpaired, retrospective, case-control study. The case group included all patients over 100 years of age who were admitted for surgical treatment after a hip fracture between January 2009 and December 2019, obtaining a total of 24 patients. For each case, 2 controls aged between 80 and 90 years were included from the general series of a total of 2935 hip fractures admitted for surgical treatment over the same period.

In our autonomous community, the average age for hip fracture is 86.7 years,17 as Aragon is a very elderly community. Therefore, we selected a control group aged 80–90 years of age, which is intended to represent a population group more closely matched to the current hip fracture population. For the controls we used simple randomisation using the mathematical formula of X+2, resulting in a total of 48 patients in the control group.18 Therefore, the overall sample for analysis included 72 patients.9,13

We have what is termed shared care19,20 in our hospital, in which an internist is responsible for assessing all patients from admission to discharge. Prior to surgery, the patients were assessed by the internal medicine department, who evaluated their baseline condition, and their previous conditions were stabilised as far as possible. Preoperative optimisation was used for blood saving,21 administering a regimen of iron sucrose 200mg every 48h (3 doses), and a single dose of erythropoietin 40,000U if preoperative haemoglobin was less than 13g/dl. Antiplatelet medication was replaced with ASA 100mg, which was discontinued 24h before surgery. Anticoagulant therapy was replaced by low molecular weight heparin at a prophylactic (40mg/24h), or therapeutic dose depending on the case, which was discontinued at least 12h before surgery. All the patients followed a restrictive transfusion strategy according to the Seville Consensus Document,22 transfusing patients with acute symptomatic anaemia, with a haemoglobin<9g/dl before surgery, a haemoglobin<8g/dl in patients with a cardiovascular or neurological history, or a haemoglobin<7g/dl in patients with no previous disease.

In terms of surgery, extracapsular fractures were operated by short or long cephalomedullary nailing depending on the type of fracture, and intracapsular fractures by cemented bipolar partial arthroplasty in all cases.

Data were collected on socio-demographic variables (age, sex), standard and age-adjusted Charlson index,23 number and type of comorbidities, use of anti-aggregants or anticoagulants, type of fracture and intervention, days of surgical delay, presence, and type of complications during admission (including medical complications, those related to surgery, or in-hospital mortality), and length of hospital stay. After discharge, we analysed the need for admission within the first month, within the first 3 months and within the first year, as well as early and 6-month mortality, and survival after one year. In terms of functionality, we analysed return to previous activity. The data were obtained by reviewing the hospital's electronic medical records.

Statistical analysisThe statistical analysis was performed with SPSS® version 20 (IBM Corporation, New York, USA). The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was used to assess the normality of the distribution of the variables (n>30). The homogeneity of the cohorts was checked by comparing the independent variables (sex, type of fracture, type of implant, comorbidity, etc.). The qualitative variables were described by their frequency distribution (number and percentages). Quantitative variables were described by mean and standard deviation. Age was separated from this initial analysis, as it is a differentiating criterion between cases and controls. For hypothesis testing in the case of qualitative variables, the χ2 test and/or Fisher's exact test was used, with Yates’ correction where necessary. In the case of quantitative variables, a Student's t-test or Mann–Whitney U-test was performed if the variable did not follow a normal distribution. Survival was estimated using a Kaplan–Meier test, with patient death as the end-point. The overall level of significance was p<.05.

ResultsA total of 24 centenarian hip fracture patients and 48 patients aged 80–90 years were analysed after randomisation to the control group. The mean age of the control group was 85.50 years (80–90) compared to 101.13 in the centenarian group (100–104). In both groups, the patients were predominantly female (centenarians 87.5%, controls 81.25%), and extracapsular fractures were more common than intracapsular fractures (centenarians 75%, controls 60.42%). The Charlson index showed no differences between the two groups (p=.919): mean of 1.67 in the centenarians and of 1.71 in the controls. The preoperative delay was longer in the centenarian group, with a mean of 3.98 days compared to 2.82 in the control group, but this difference was not statistically significant (p=.071). Hospital stay was significantly longer in the control group, with a mean of 12.58 days compared to 9.58 days in the centenarians (p=0.038). Table 1 provides a summary of the characteristics of both groups.

Comparison of the participants’ baseline characteristics.

| Centenarians | 80–90-year-olds | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years, mean (range) | 101.13 (100–104) | 85.50 (80–90) | <.001 |

| Sex (F/M) | 21/3 | 39/9 | .737 |

| Charlson, mean (SD) | 1.67 (1.43) | 1.71 (1.71) | .919 |

| Adjusted Charlson, mean (SD) | 6.67 (1.435) | 5.81 (1.684) | 0.037 |

| Previous diseases, mean (SD) | 1.46 (.833) | 1.71 (.944) | 0.275 |

| Dementia, n (%) | 6 (25) | 11 (22.9) | .844 |

| CVA, n (%) | 4 (16) | 3 (6.25) | .325 |

| AMI, n (%) | 1 (4.2) | 6 (12.5) | .412 |

| Neoplasia, n (%) | 1 (4.2) | 7 (14.6) | .225 |

| Depression, n (%) | 1 (4.2) | 5 (10.4) | .432 |

| Anti-aggregation medication, n (%) | 1 (4.2) | 16 (33.3) | .007 |

| Surgical delay, mean (SD) | 2.82 (2.73) | 3.98 (2.37) | .071 |

| Intracapsular fracture, n (%) | 6 (25) | 18 (37.5) | .294 |

| Type of surgery, n (%) | |||

| Not operated due to death | 2 (8.3) | 2 (4.16) | .467 |

| Hemiarthroplasty | 5 (20.8) | 17 (35.4) | .384 |

| CMN | 17 (70.8) | 29 (60.4) | .211 |

| Baseline functional data, n (%) | |||

| Bed-chair life | 10 (41.7) | 6 (12.5) | .005 |

| Walking with or without aids | 14 (58.3) | 42 (87.5) | |

| Hospital stay, mean (SD) | 9.58 (4.76) | 12.58 (7.02) | <.001 |

CVA: cerebrovascular accident; SD: standard deviation; CMN: centromedullary nailing; M: male; AMI: acute myocardial infarction; F: female.

All the patients in the centenarian group suffered some complication during admission; there were more complications in this group compared to the control (p=.02). The most frequent in-hospital complication was anaemia requiring allogeneic blood transfusion, with a higher incidence in the centenarian group (p<.0001). Of the remaining complications, there was a higher incidence of urinary tract infections in the control group (p=.025) and a higher incidence of respiratory failure in the centenarian group (p=.039). In-hospital mortality was also higher in the centenarian group, at 33% of the sample versus 10% in the octogenarian group (p=.017), with a mortality OR of 4.3 (1.224–15.101) in the centenarians. The main in-hospital complications in both groups are shown in Table 2.

In-hospital complications and discharge to long-stay hospitals.

| Centenarians | 80–90-year-olds | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Presence of complications, n (%) | 24 (100) | 25 (52.1) | <.0001 |

| Number of complications, mean (SD) | 1.96 (1.04) | 1.04 (1.32) | .02 |

| Transfusion, n (%) | 23 (95.8) | 9 (18.8) | <.0001 |

| Bowel obstruction, n (%) | 0 (0) | 3 (6.3) | .546 |

| Pneumonia, n (%) | 4 (16.7) | 6 (12.5) | .630 |

| UTI, n (%) | 0 (0) | 9 (18.8) | .025 |

| Respiratory failure, n (%) | 4 (16.7) | 1 (2.1) | .039 |

| Hear failure, n (%) | 5 (20.5) | 3 (6.3) | .145 |

| Anaemia at discharge, n (%) | 6 (25) | 9 (18.8) | .538 |

| Digestive haemorrhage, n (%) | 0 (0) | 2 (4.2) | .549 |

| APO, n (%) | 1 (4.2) | 1 (2.1) | 1 |

| Sepsis, n (%) | 0 (0) | 2 (4.2) | .549 |

| Hypovolemic shock, n (%) | 0 (0) | 1 (2.1) | 1 |

| Cardiac arrythmia, n (%) | 1 (4.2) | 1 (2.1) | 1 |

| Haematuria, n (%) | 0 (0) | 2 (4.2) | .549 |

| Acute renal failure, n (%) | 2 (8.3) | 1 (2.1) | .256 |

| Portal hypertension, n (%) | 1 (4.2) | 0 (0) | .333 |

| Acute material failure, n (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 |

| Prosthetic dislocation, n (%) | 1 (4.2) | 0 (0) | .333 |

| In-hospital mortality, n (%) | 8 (33) | 5 (10.5) | .017 |

| Discharge to intermediate care hospital, n (%) | 1 (4.2) | 9 (18.8) | .006 |

APO: acute pulmonary oedema; UTI: urinary tract infection.

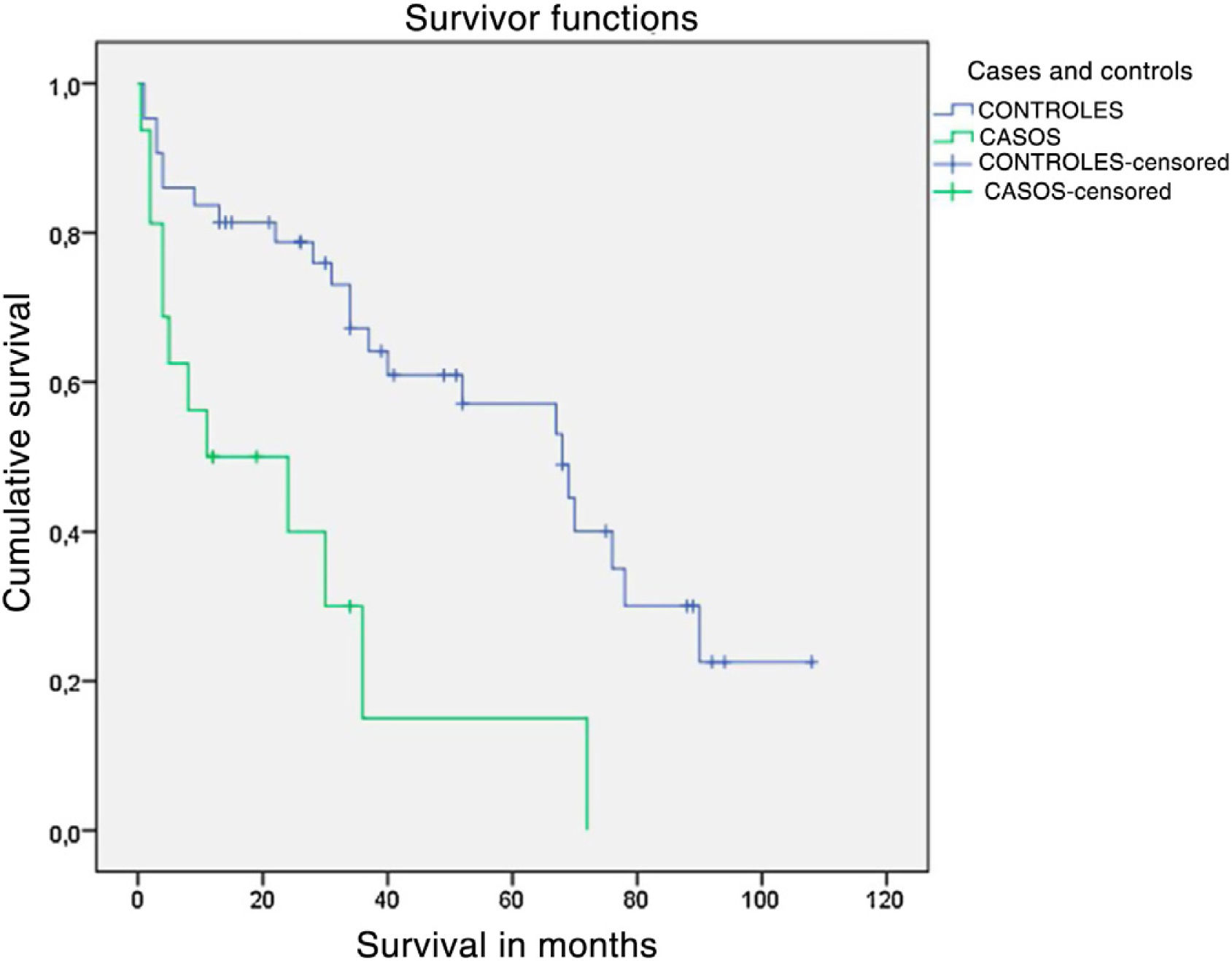

After discharge, the total sample was reduced to 59 patients, 66% of the centenarians and 89.5% of the control group, for assessment of functionality, post-discharge complications, and mortality at 6 months and 1 year. The results indicate that age did not condition hospital readmission, although in absolute values it was higher in percentage terms in the older patients. Mortality in the first 6 months after discharge also showed significance in this group, with an OR of 4.62 (1.044–20.498), p=.048. Table 3 gives a summary of readmissions and mortality in the series. According to the results of the Kaplan–Meier survival curve, the mortality of centenarians continues to increase over time, making it unlikely that the patient will survive after the first 24 months following the fracture (>90% cumulative mortality), whereas fewer of the octogenarian group die and up to 75% of cases survive 2 years after the fracture (Fig. 1). In terms of functionality, at the end of follow-up only 2 centenarian patients managed a return to walking with a walking frame after the intervention, whereas in the group of controls 53.84% returned to their previous functional situation (p=.003 and OR=5.27 [1.35–20.52]).

Follow-up and mortality of the series.

| Centenarians | 89–90-year-olds | OR (CI)/p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Readmission<30 days, n (%) | 2 (13.3) | 3 (7.3) | ns/.602 |

| Readmission 3 months, n (%) | 2 (15.44) | 6 (14.6) | ns/1 |

| Readmission first year, n (%) | 2 (23.1) | 12 (29.3) | ns/.664 |

| Mortality at 30 days, n (%) | 2 (6.3) | 2 (4.7) | ns/1 |

| Mortality at 6 months, n (%) | 5 (33) | 4 (9.8) | 4.62 (1.044–20.498)/.048a |

| Mortality at one year, n (%) | 1 (11) | 1 (2.7) | ns/.110 |

| Survival>1 year, n (%)a | 8 (33) | 36 (75) | – |

CI: confidence interval; ns: not significant; OR: odds ratio.

Our series is demographically like others published, with a predominance of the female sex and of extracapsular fractures.6,8 In the sample under study, the homogeneity between the two groups in terms of their baseline characteristics is noteworthy, with only significant differences observed in the use of antiplatelet/anticoagulants, and the age-adjusted Charlson index. It is interesting that it was the control group that took more antiplatelet/anticoagulants, probably because some authors recommend discontinuing treatment in older patients as it does not provide a clear clinical benefit.24,25 These data are consistent with similar studies where no differences in comorbidity were found between centenarian and younger patients.9,13 However, there is controversy on this point. Authors such as Holt et al.26 state that patients of extreme age present greater comorbidities and a more precarious baseline state.

For subcapital hip fracture, we systematically use bipolar implants because they are available in our centre. Recent meta-analyses recientes27,28 confirm that the bipolar prosthesis design provides a better range of motion and a better functional result, with less acetabular wear, with no difference in dislocation or reoperation rates compared to monopolar prostheses. Nevertheless, we believe that the bipolar design would be more suitable for elderly patients with longer life expectancy and some activity, whereas the monopolar design could be useful for those with very few functional demands.

Centenarian patients tend to present a greater number of complications during hospital admission for any cause.9,26 According to the data obtained in our series, all the centenarian patients suffered some kind of complication while in hospital. Their most frequent complication was allogeneic blood transfusion (95.8% vs. 18.8% in the controls). This contradicts the study by Pelavski Atlas et al.29 who found no difference in the number of patients transfused in the different age groups. The reported transfusion rates vary greatly, although they are high (up to 75%).29,30 The great variability may be due to non-homogeneous criteria for transfusion.30 No significant differences were found in the type or number of other complications, like that reported by Barceló et al.,13 except for a higher incidence of respiratory failure. This difference found in the number of postoperative transfusions could have an explanation. The centenarians were more dehydrated on admission, and therefore their haematocrit values appear higher. Therefore, after surgery, and once properly hydrated, their haemoglobin values were significantly lower.29

Several studies claim that the hospital stay of centenarians was higher than in control groups of younger patients8,9; however, studies with large cohorts of a larger sample size do not find this association.12,26 In our study, the group of octogenarians had a significantly longer hospital stay than the group of centenarians by an average of 3 days, although this difference could be due to bias, as the centenarians had higher in-hospital mortality.

In-hospital mortality in the centenarians was 33% according to the data obtained, very similar to the 31% reported by Forster and Calthorpe,10 but higher than that reported by other authors, where it is around 9–10%,6,7,11,12 compared to 10.5% in octogenarians. Foss and Kehlet31 demonstrated that 43% of in-hospital deaths from hip fractures can be considered unavoidable, as they are due to severe pre-existing conditions. The rest of the complications are potentially avoidable, although in many of them (34%) therapeutic effort is limited due to the patient's poor functional and mental status. The most frequent in-hospital complications in our centenarians were anaemia, congestive heart failure, and pneumonia. Precise fluid control in the postoperative period can prevent the patient from developing pulmonary oedema or dilutional anaemia, both of which are poorly tolerated by this type of patient. A multidisciplinary team and individualised daily patient care are essential to reduce the incidence of these medical complications.32 This has resulted in shared care between traumatology and internal medicine. In centres that do not have an orthogeriatric department, the medical specialist oversees the patient's pre-existing and new medical problems, from admission to discharge, without the need to be consulted. This model makes it possible to choose the right surgical moment, differentiating patients who will benefit from early surgery from those who will require medical optimisation prior to surgery, favouring early rehabilitation and functional recovery, and reducing mortality.19,20

In the centenarians, the cumulative mortality at 6 months was more than 43%, twice as high as in the octogenarians, and these differences were maintained after one year. These results are like those found by other authors. Tarity et al. found a 3-month mortality of around 30%,7 and Oliver and Burke a 4-month mortality of 50% in centenarians, but only 5.6% in patients aged 75–83 years.6

The mortality of hip fractures during the first year is estimated at between 14% and 36%33 regardless of age. Specifically in centenarians, Shabat et al.,8 Forster and Calthorpe,10 Barceló et al.,13 and Moore et al.14 found a mortality in the first year of 42%, 56%, 60%, and 71%, respectively. We report a cumulative mortality in the first year of 67%, which is slightly higher than that reported by other authors.7,8,33 In the group of octogenarians it is like the estimated mortality, regardless of age (25%).34

Regarding functional status, it should be noted that between 40%-60% of hip fracture patients will recover their pre-fracture functional activity.35,36 Of the sample of centenarians who were discharged from hospital, only 56.25% were able to walk with some form of assistance before the fall, compared to 90.6% of the control group. Our study shows that 22.2% of the centenarian patients recovered their functional status, compared to 53.84% of the control group.

The present study has some limitations. Firstly, we must mention the case–control design with exclusive randomisation in the control group. This design allowed us to increase the n of the case group as the sample of centenarian patients is very small, but it may induce a selection bias that should be considered. The homogeneity of the groups in terms of baseline characteristics and antiplatelet control means that, in our opinion, the sample is of sufficient quality for analysis. Finally, the loss of patients due to high mortality meant that the statistical analysis of the last phases of the study was performed with tests of lower power, and therefore the significance of the results should be interpreted with caution.

From the data obtained after the analysis we can conclude that there are no relevant differences in the baseline characteristics of the patients of extreme age compared to the most representative group among those affected by hip fracture. However, in-hospital mortality and mortality in the first year following the fracture is significantly higher in the centenarians and very few recover their pre-fracture activity. Therefore, on admission, the focus should be on informing the patient and family members, identifying risk factors for mortality and controlling complications. Further studies are necessary to analyse these factors.

FundingThe authors declare that they do not have external funding to carry out this study.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.