Describe the population incidence of hip arthroscopy from 1998 to 2018 and to project the trends for the year 2030, as well as to describe the variations in the population incidence between the autonomous communities.

Material and methodA retrospective review of the minimum basic data set from 1998 to 2018 was carried out. Temporal evolution was analysed and the variables associated with the indication (age, sex, regions) were identified. For each region, the crude rate per 100,000 inhabitants was calculated. The 2019–2030 projection was made using linear regression.

ResultsIn Spain between 1998 and 2018 a total of 10,663 arthroscopic hip surgeries were carried out. The population incidence in 1998 was 0.14 CAC per 100,000 inhabitants, while in 2018 it was 4.09. For the year 2030 an increase of 156.9% in the number of arthroscopic hip surgeries is expected (p<.001). On average, 57.7% of all procedures (95% CI 55.2–60.2) were done in men and the highest incidence was found in ages≤44 years. The geographical variation was 81%, being up to 15.4 times the difference in incidence per 100,000 inhabitants between some regions.

ConclusionsThe number of hip arthroscopies in Spain has been increasing in the 1998–2018 period and this growing trend is expected to continue until 2030. In Spain, hip arthroscopic procedures are performed more frequently in male patients and in under 45 years old. The variability of the population incidence between the autonomous communities is high.

Describir la incidencia poblacional de la artroscopia de cadera desde 1998 hasta 2018 y proyectar las tendencias para el año 2030, así como describir las variaciones en la incidencia poblacional entre las comunidades autónomas (CC. AA.).

Material y métodoSe realizó una revisión retrospectiva del conjunto mínimo básico de datos de 1998-2018. Se analizó su evolución temporal y se identificaron las variables asociadas con la indicación (edad, sexo y CC. AA.). Por cada comunidad autónoma se calculó la tasa cruda por 100.000 habitantes. Se realizó la proyección 2019-2030 para España mediante regresión lineal.

ResultadosEn España entre 1998 y 2018 se realizaron un total de 10.663 CAC. La incidencia poblacional en 1998 era de 0,14 CAC por cada 100.000 habitantes, mientras que para 2018 era de 4,09. Con respecto a 2018, para el año 2030 se espera un incremento del 156,9% en el número de CAC (p<0,001). En promedio las CAC en hombres representaron el 57,7% (IC 95%: 55,2-60,2) de todos los procedimientos y la mayor incidencia se encontró en edades≤44 años. La variación geográfica es del 81%, siendo la diferencia de incidencia por 100.000 habitantes de hasta 15,4 veces entre algunas CC. AA.

ConclusionesEl número de artroscopias de cadera en España ha ido en aumento en el periodo 1998-2018, y se prevé que esta tendencia creciente continúe hasta el año 2030. En España los procedimientos artroscópicos de cadera se realizan con más frecuencia en pacientes hombres y en menores de 45 años. La variabilidad de la incidencia poblacional entre las CC. AA. es alta.

Arthroscopic surgery is adopted for an increasing number of hip conditions. For acute procedures, joint irrigation can be performed arthroscopically for the treatment of septic arthritis.1 Fixation of femoral head fractures is also possible arthroscopically.2 In an elective setting hip arthroscopy is used in the treatment of a variety of intracapsular conditions including femoroacetabular impingement (FAI),3 labral involvement,4 chondral lesions5 or for the treatment of extracapsular disease including iliopsoas tendon and iliotibial band involvement6 as well as procedures in the deep gluteal space.7

Hip arthroscopy was first described in 19318 although its implementation has only been possible more recently after technical advances were made that allow adequate distraction of the femoral head from the acetabulum and joint instrumentation with arthroscopic devices.9 The arthroscopic approach confers potential benefits over open surgery and most studies report lower complication rates and outcomes equal to or better than open surgery.10

Every year a growing number of hip arthroscopies procedures are performed throughout the world. In Korea the number of these procedures doubled between 2007 and 2010.11 In the U.S.A., depending on the register studied, there was an increase of 365% between 2004 and 200912 and of 250% between 2007 and 2011.13 In the United Kingdom there was an increase of 483% between 2012 and 2018.14

The uptake of hip arthroscopy in Spain has not been described. The aim of this study is to describe the population incidence of hip arthroscopy from 1998 to 2018 and to project trends to the year 2030 as well as to describe variations in population incidence between autonomous communities (ACs). The publication of temporal trends can help surgeons and decision-making bodies. Regional variation is of particular interest, given the perceived inequalities in the health services landscape.

Material and methodsThis study is of observational epidemiological research study design. The data came from an anonymised public database and therefore did not require approval by a research committee.

Using the Core Minimum Data Set (CMBD)15 a retrospective review of procedures performed in 1998 and 2018 was performed. The CMBD records all hospital discharges from the National Health System using the International Classification of Diseases ninth edition (ICD-9) from 1997 to 2015 and tenth edition (ICD-10) from 2016. Discharge episodes of “hospitalisation” in which a hip arthroscopy procedure was performed were identified as defined as “main procedure” with code “80.25” (ICD-9) and “endoscopic-percutaneous” in ICD-10 performed on “lower joints” included in clinical classification codes 149 “arthroscopy”, 150 “Division of joint capsule, ligament or cartilage”, and 162 “Other therapeutic procedures with use of operating theatre on joints”. The latter was done to homogenise coding results due to the ICD change in 2016. The clinical classification codes are the same in both versions. ICD-10 procedures included were “drainage”, “excision”, “insertion”, “inspection”, “release”, “repair” and “supplement”. Excluded procedures were “exchange”, “destruction”, “excision”, “fusion”, “removal”, “repositioning”, “resection” and “revision”. In turn, to limit errors, coding was done with other procedures and age groups were limited to those between 15 and 74 years of age.

The anonymised data included the age and sex of the patient and the autonomous community of the centre. For each region, the number of procedures performed and the crude rate per 10.000 inhabitants were calculated, using as denominator the data by sex and age provided by the National Institute of Statistics.16 Considering 2 periods: 1998–2018 (full period) and 2008–2018 (last available decade), the 2019–2030 projection for Spain was made using linear regression and 95% prediction intervals were provided. For these projections we calculated the significance, the model fit using the coefficient of determination (R2) and the mean absolute percentage error (MAPE), which expresses the accuracy as a percentage of the error. The time trend by Autonomous Community was also studied. Geographical variations were studied by means of the ratio of variation of the maximums and minimums and the coefficient of variation. Statistical analysis was carried out using SPSS (IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 22.0. USA) and Excel (Office Excel, Microsoft Office Professional Plus 2016. USA). In all tests, a p-significance level of less than .05 bilateral was considered.

ResultsTotal number of procedures and population incidenceA total of 1663 hip arthroscopies were performed in Spanish National Health System hospitals between 1998 and 2018. Between 1998 and 2018 the number of AHS increased from 42 to 1447, which represents an increase of 34.45 times.

When we look at the population incidence in 1998 there were .14 AHS per 10.000 inhabitants, while by 2018 there were 4.09 AHS per 10.000 inhabitants. For the period 1998–2008 the population growth was 423.4%, while for the period 2008–2018 it was 715.0%.

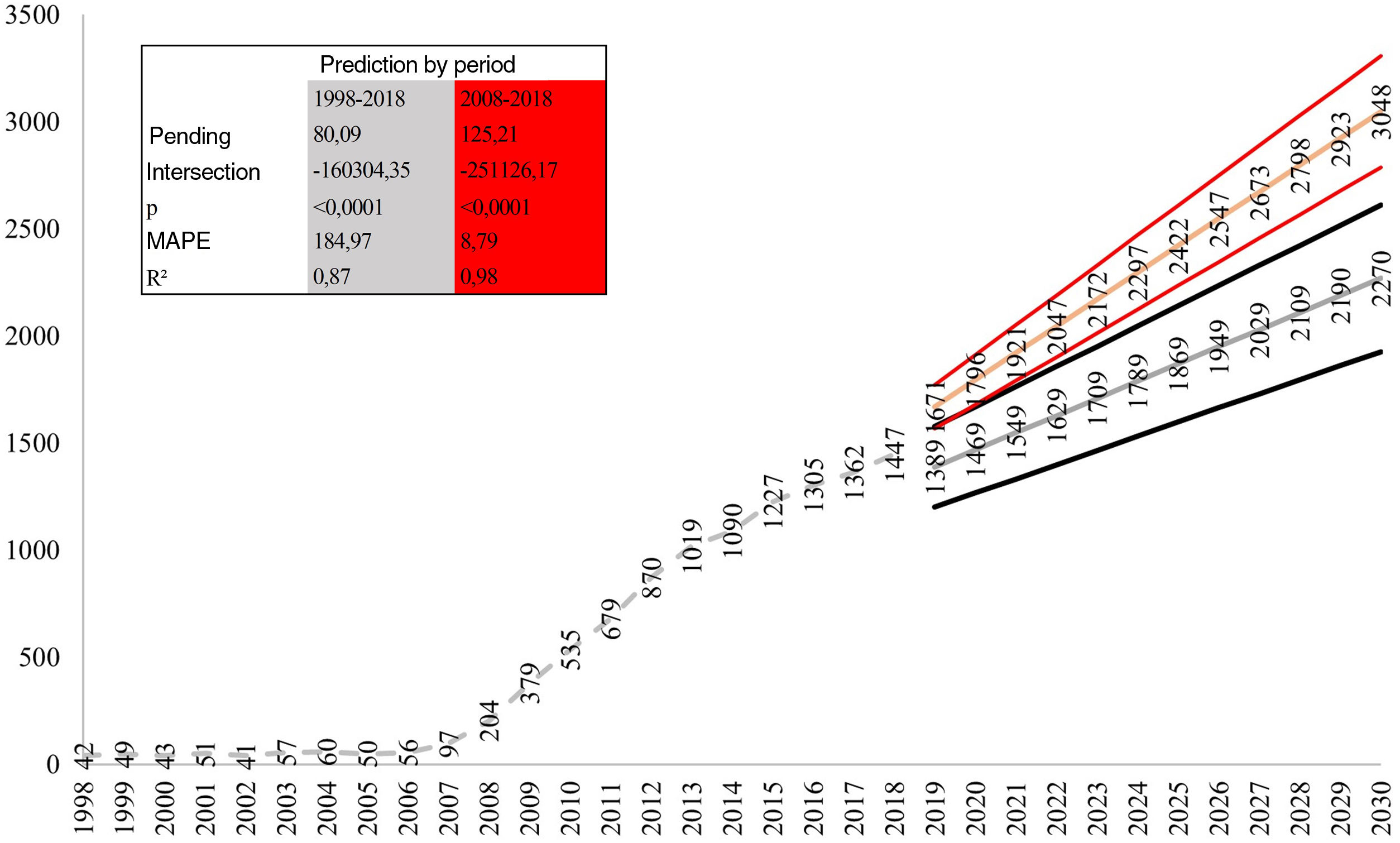

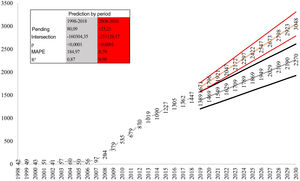

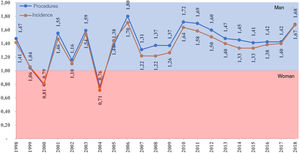

Compared to 2018, an increase of between 156.9% (1988–2018 period; MAPE 184.9%) and 210.7% (2008–2018 period; MAPE 8.8%) in the number of procedures (p<.001) is expected by 2030 (Fig. 1).

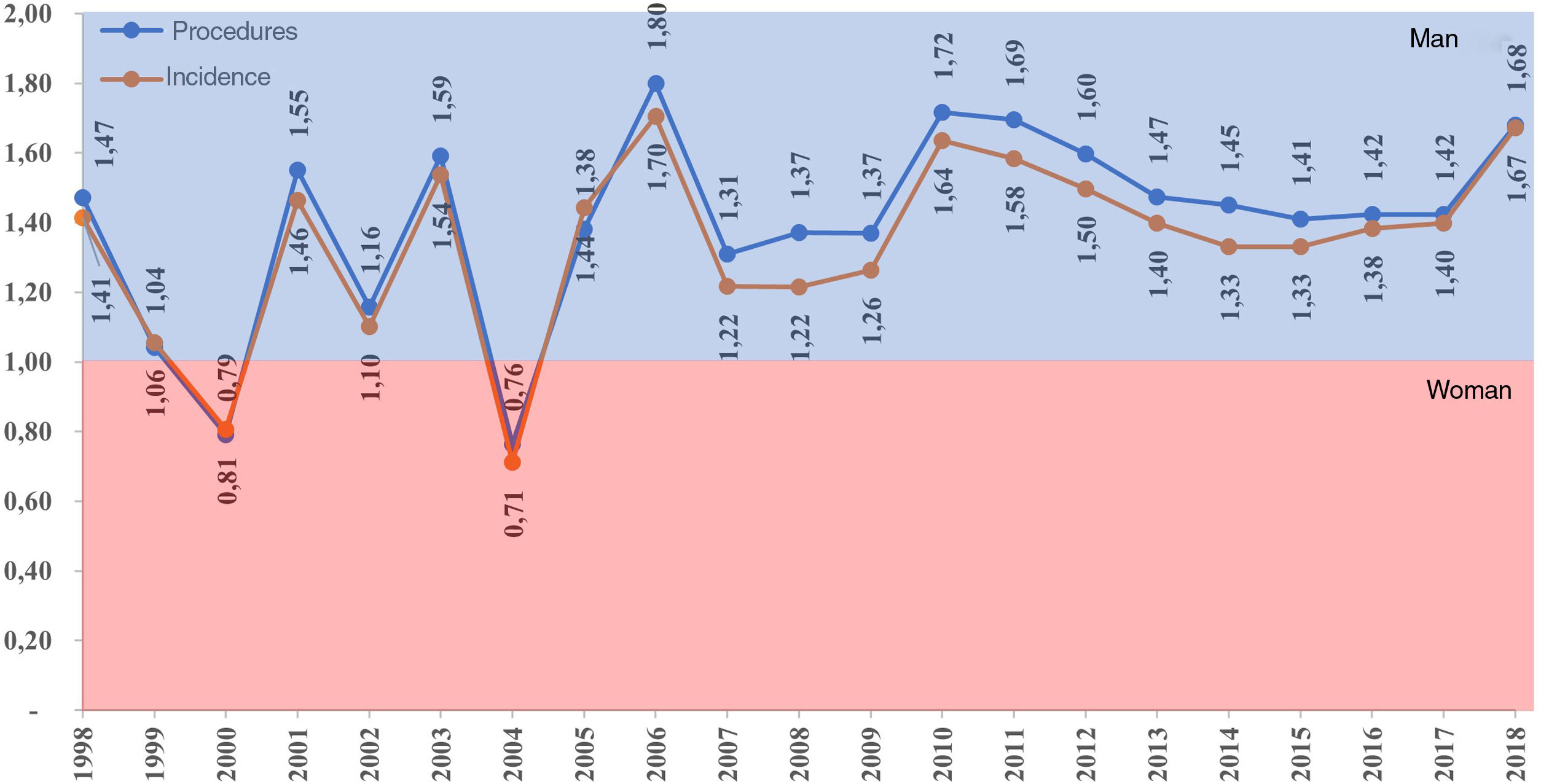

Demographic patient dataIn Spain, arthroscopic hip procedures are more frequently performed in men. For the whole period under study, on average, AHS in men accounted for 57.7% (95% CI: 55.2–60.2) of all procedures, with the mean male/female ratio of procedures being 1.40 (95% CI: 1.27–1.52) and the incidence 1.34 (95% CI: 1.22–1.45) in favour of men (Fig. 2).

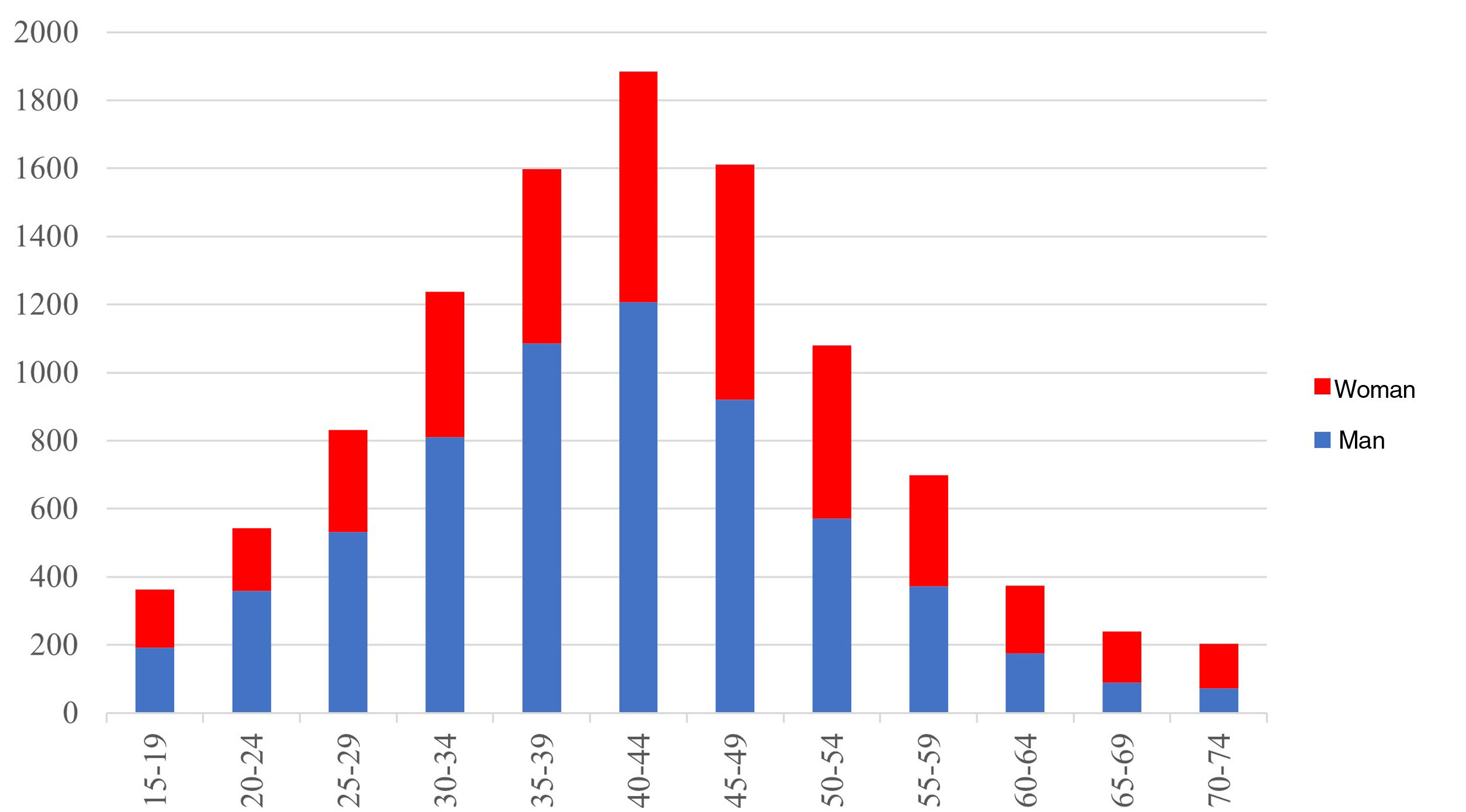

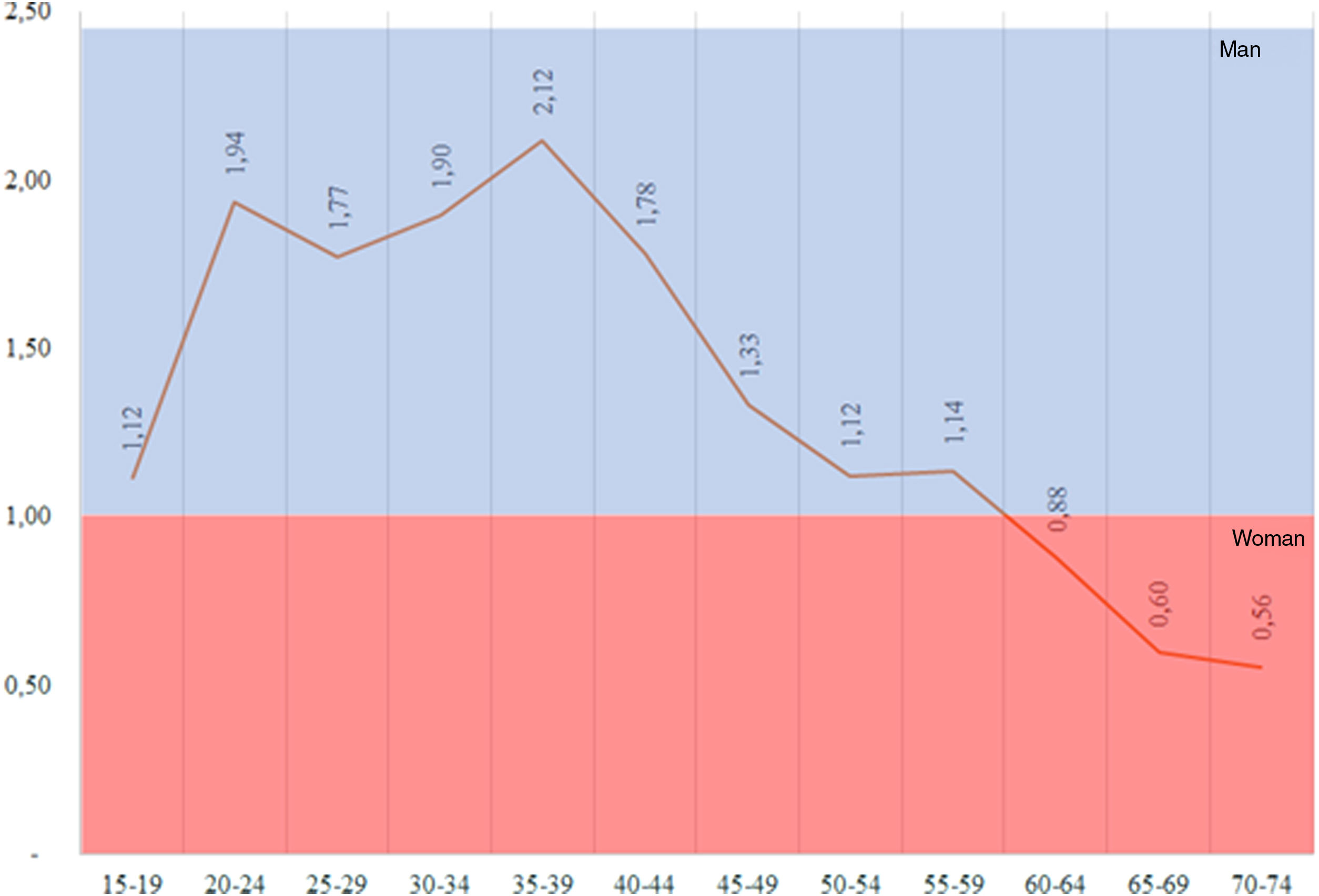

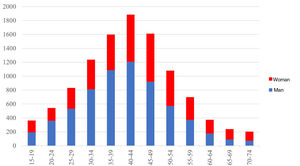

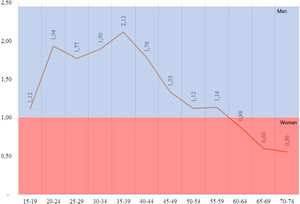

The age group with the highest percentage of procedures was patients aged 40–44 years (17.7% of the total) (Fig. 3). Men accumulated the highest ratio of interventions at younger ages, more than doubling between 35 and 39 years of age, with this ratio decreasing with increasing age and becoming higher in women over 60 years of age (Fig. 4).

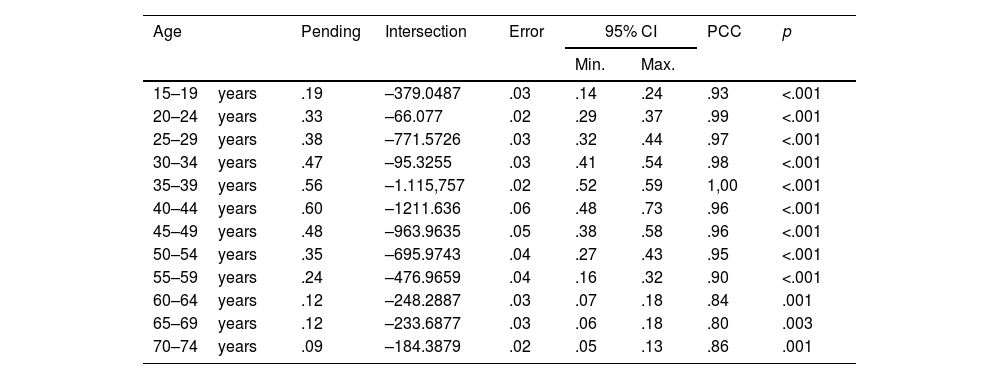

Similarly, the age group with the highest growth since 2008 is that of ages between 40 and 44 years. All age groups have increased significantly. On average, the highest growth was found in ages≤44years (Table 1).

Trend of the population incidence by age groups during the 2008–2018 period.

| Age | Pending | Intersection | Error | 95% CI | PCC | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Min. | Max. | ||||||

| 15–19years | .19 | –379.0487 | .03 | .14 | .24 | .93 | <.001 |

| 20–24years | .33 | –66.077 | .02 | .29 | .37 | .99 | <.001 |

| 25–29years | .38 | –771.5726 | .03 | .32 | .44 | .97 | <.001 |

| 30–34years | .47 | –95.3255 | .03 | .41 | .54 | .98 | <.001 |

| 35–39years | .56 | –1.115,757 | .02 | .52 | .59 | 1,00 | <.001 |

| 40–44years | .60 | –1211.636 | .06 | .48 | .73 | .96 | <.001 |

| 45–49years | .48 | –963.9635 | .05 | .38 | .58 | .96 | <.001 |

| 50–54years | .35 | –695.9743 | .04 | .27 | .43 | .95 | <.001 |

| 55–59years | .24 | –476.9659 | .04 | .16 | .32 | .90 | <.001 |

| 60–64years | .12 | –248.2887 | .03 | .07 | .18 | .84 | .001 |

| 65–69years | .12 | –233.6877 | .03 | .06 | .18 | .80 | .003 |

| 70–74years | .09 | –184.3879 | .02 | .05 | .13 | .86 | .001 |

PCC: Pearson's correlation coefficient.

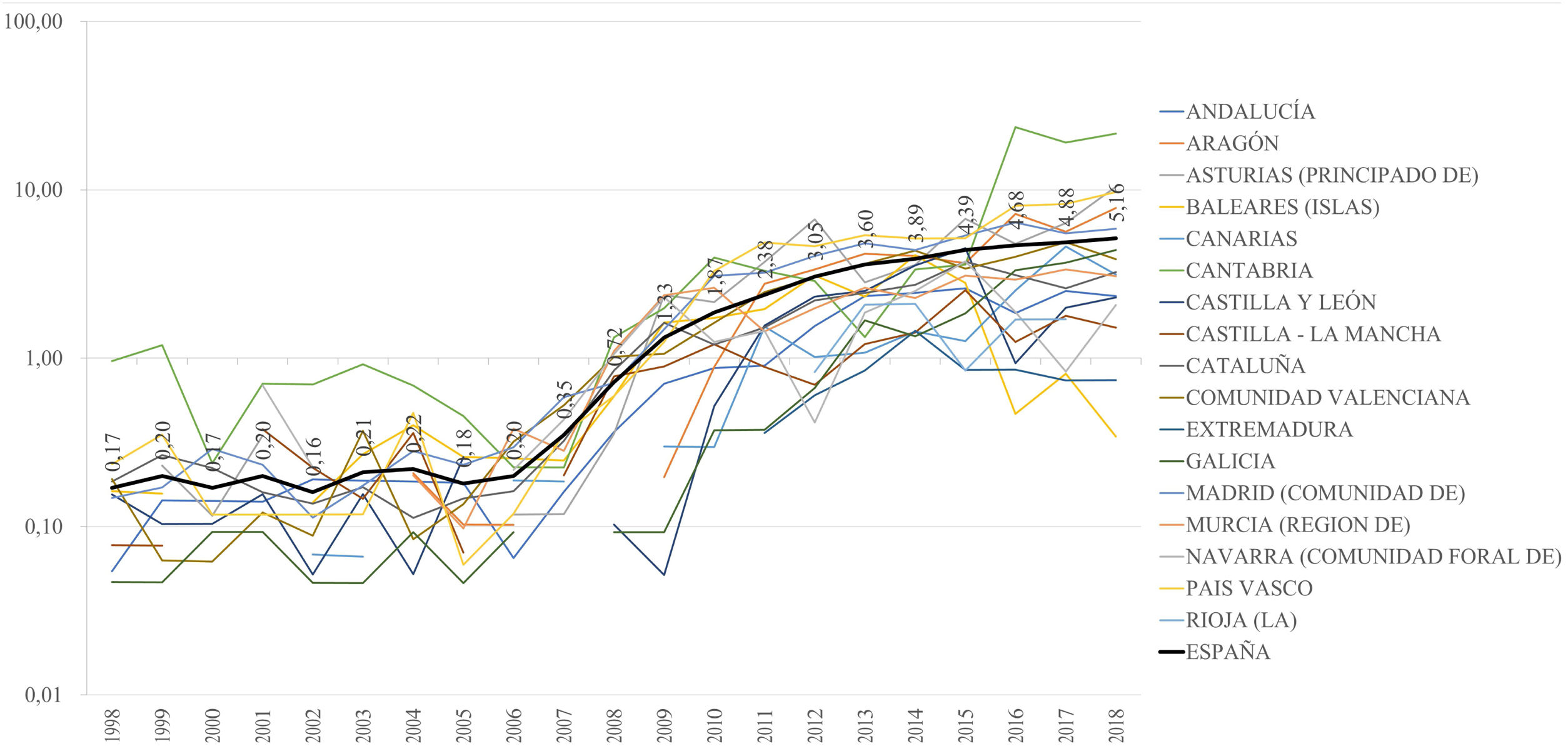

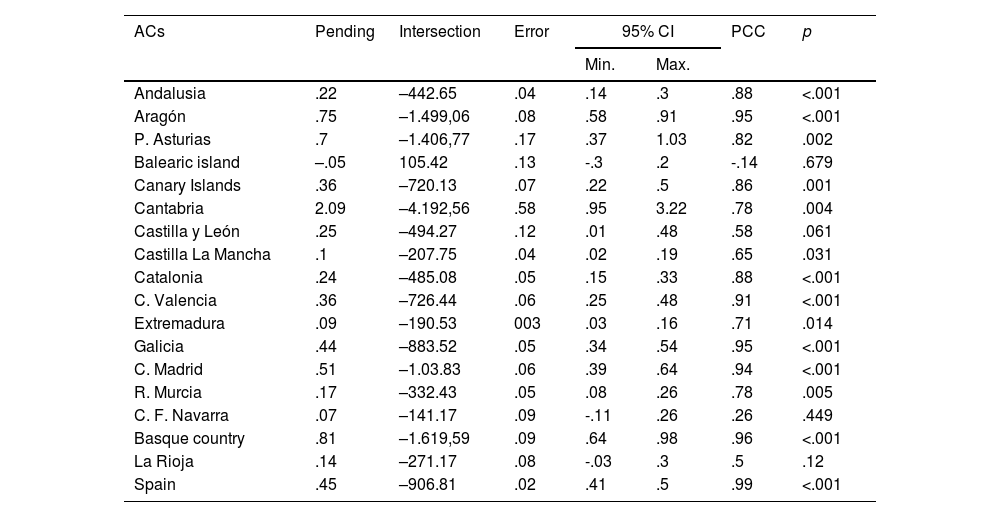

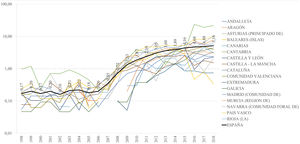

There has been a growth in the population incidence of AHS procedures in all regions (Fig. 5). In the period 2008–2018, 94.1% of the ACs presented significant growth trends (Table 2), and in the last 5 years all ACs have reported at least one hip arthroscopy procedure.

Trend of population incidence by autonomous communities during the 2008–2018 period.

| ACs | Pending | Intersection | Error | 95% CI | PCC | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Min. | Max. | ||||||

| Andalusia | .22 | –442.65 | .04 | .14 | .3 | .88 | <.001 |

| Aragón | .75 | –1.499,06 | .08 | .58 | .91 | .95 | <.001 |

| P. Asturias | .7 | –1.406,77 | .17 | .37 | 1.03 | .82 | .002 |

| Balearic island | –.05 | 105.42 | .13 | -.3 | .2 | -.14 | .679 |

| Canary Islands | .36 | –720.13 | .07 | .22 | .5 | .86 | .001 |

| Cantabria | 2.09 | –4.192,56 | .58 | .95 | 3.22 | .78 | .004 |

| Castilla y León | .25 | –494.27 | .12 | .01 | .48 | .58 | .061 |

| Castilla La Mancha | .1 | –207.75 | .04 | .02 | .19 | .65 | .031 |

| Catalonia | .24 | –485.08 | .05 | .15 | .33 | .88 | <.001 |

| C. Valencia | .36 | –726.44 | .06 | .25 | .48 | .91 | <.001 |

| Extremadura | .09 | –190.53 | 003 | .03 | .16 | .71 | .014 |

| Galicia | .44 | –883.52 | .05 | .34 | .54 | .95 | <.001 |

| C. Madrid | .51 | –1.03.83 | .06 | .39 | .64 | .94 | <.001 |

| R. Murcia | .17 | –332.43 | .05 | .08 | .26 | .78 | .005 |

| C. F. Navarra | .07 | –141.17 | .09 | -.11 | .26 | .26 | .449 |

| Basque country | .81 | –1.619,59 | .09 | .64 | .98 | .96 | <.001 |

| La Rioja | .14 | –271.17 | .08 | -.03 | .3 | .5 | .12 |

| Spain | .45 | –906.81 | .02 | .41 | .5 | .99 | <.001 |

ACs: autonomous communities; PCC: Pearson's correlation coefficient.

In the last 5 years studied in the ACs an average of 3.97 (95% CI: 2.3–5.6) AHS per 10,000 population have been performed. The geographical variation is 81%, with the difference between the ACs with the lowest (Extremadura .9) and highest (Cantabria 14.2) incidence per 10,000 inhabitants being 15.4 times (Fig. 6).

DiscussionOur purpose was to describe the population incidence of hip arthroscopy from 1998 to 2018 and to project trends to the year 2030. The number of arthroscopic hip procedures performed in Spain has increased by 3445.2% since 1998. However, we cannot ignore the fact that two periods can be distinguished, since a marked increase in these procedures has been observed since 2008. Thus, between 1998 and 2008 the growth was 485.7% and from 2008 to 2018 it was 709.3%. This increasing trend is expected to continue until 2030. The increase in the rate of arthroscopic hip procedures observed in Spain is in line with that reported in Korea,11 U.S.A.12,13 and England.17

Several factors are likely to be driving the increasing number of hip arthroscopies: (1) conditions such as femoroacetabular impingement and labral tears are increasingly recognised as a source of pain and osteoarthritis18 by both clinicians and patients; (2) good short- and medium-term outcomes for a wide range of arthroscopic hip procedures,19,20 (3) the support of health institutions such as the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) in the UK, which in 2011 concluded that there was adequate evidence to indicate AHS in FAI21 and endorsed by the Health Technology Assessment Programme of the National Institute of Health Research in 2018,22 which concluded that compared to conservative treatment hip arthroscopy produced better outcomes, and this difference was clinically significant; (4) in the USA, there was an 18-fold increase in the number of hip arthroscopies performed by candidates of the American Board of Orthopaedic Surgery between 1999 and 2009,8 and a 600% increase between 2006 and 201.24 with hip arthroscopy now an established procedure in training programmes in the USA.

In contrast to England14,17 and the U.S.A.12,13 in Spain hip arthroscopy is performed more frequently in men than in women, and this has remained virtually unchanged during the study period. The higher number of procedures in men observed in our study is consistent with the fact that FAI, one of the most frequent indications for hip arthroscopy,23 is more prevalent in men.24

The age at which the highest percentage of hip arthroscopies are performed is between 40 and 44 years. Analysing the sex ratio, we observe that men tend to be younger than women at the time of surgery. These findings are consistent with data observed in England17 and the U.S.A.12,13 In Spain, in contrast to the U.S.A.13 the greatest increase in the number of procedures was observed in patients≤44 years. This may be related to the publication of good results in active young adults who are able to return to high-level sporting activities.25 In contrast, the results are worse in older patients.26

There is significant regional variation in the incidence of hip arthroscopy in Spain. Considering the last 5 years, the highest incidence is observed in Cantabria and the lowest in Extremadura. Regional variation is also observed in the U.S.A., being 2.05 times between regionss12 and in England, 6.69 times.17 However, in our study the differences are extreme, reaching almost 15 times. If we consider less marked ranges, limiting the differences to the 5–95 percentiles, these differences decrease to 7.2 times. The latter is perhaps a more appropriate figure considering that the extreme regions account for only 3.66% of the population. Likewise, our analysis is divided into 17 regions or Autonomous Communities whereas the US and UK analyses are divided into 4 and 5 respectively. This may be a source of variability, considering that in Spain there are regions with relatively small populations.

It is difficult to establish the factors influencing the incidence of AHS by region. The key factors are likely to be local expertise in hip arthroscopy, making it “supply-sensitive care”.27,28 This type of care often corresponds to technology or services characterised by a paucity of evidence about their value in specific circumstances, with significant discrepancies about their indication, and which have utilisation rates positively associated with resource availability,27,28 so the results of robust clinical trials and surgeon training may lead to more standardised care. The latter is particularly important, given that the procedure has a steep learning curve.29

Our best-case prediction (analysing the period 2008–2018) gives an increase in the number of arthroscopic hip procedures of up to 210.7% by 2030. This will accentuate the need for professional training in this procedure and incentive from the state. It is difficult to quantify the cost of hip arthroscopy procedures due to their heterogeneous nature. However, these procedures appear to be cost-effective. A study in the US estimated an average direct cost of $11,850 for arthroscopic treatment of femoroacetabular impingement, and concluded that this was cost-effective in patients without evidence of osteoarthritis at $21,700 per quality-adjusted life year.30 These results were replicated in a study from Scotland with an estimated cost of £19,335 per quality-adjusted life-year, meeting the NICE threshold for cost-effective inventions.31

The main limitation of this study is that, as with any large administrative database, data entry in the CMBD may be subject to errors or inaccurate coding. Similarly, the effect of changes in ICD coding that occurred during the study period is difficult to determine. Likewise, it is not possible to know the number of surgeons specialised in hip arthroscopy for each AC, which would probably be one of the most important factors in determining the number of surgeons specialised in hip arthroscopy. This would probably be one of the explanatory factors for the observed variations. Therefore, our results should be interpreted with caution. Despite these limitations, we believe that the large sample of patients included in our analysis allows us to draw plausible conclusions about trends in the use of AHS in Spain.

It is clear that the number of arthroscopic procedures continues to increase in Spain in line with observations from other countries such as the U.S.A., England and Korea. This increase has been greatest in male patients and in those under 44 years of age. This increasing trend is expected to continue until 2030 and strong evidence of the clinical efficacy of AHS is required, and research priorities should reflect the changing nature of the delivery of this healthcare. A growing demand for hip arthroscopy may also have implications for rehabilitation, physiotherapy and the training of orthopaedic surgeons. Similarly, as the utilisation of AHS increases, policies should be implemented to decrease the high variability of its use among the different ACs.

ConclusionThe number of hip arthroscopies in Spain has been increasing in the period 1998–2018, and this increasing trend is expected to continue until 2030. In Spain, hip arthroscopic procedures are more frequently performed in male patients and in patients under 45 years of age. The variability of population incidence among the Autonomous Communities is high.

Level of evidenceLevel of evidence iii.

FundingThe authors declare that they have received no funding for the conduct of the present research, the preparation of the article, or its publication.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.