Retrospective review of patients with a diagnosis of Tarsal Tunnel Syndrome (TTS) treated surgically.

MethodsRetrospective series of patients with diagnosis of TTS operated between 2005 and 2020 in the same center. Variables such as age, sex, side, affected nerve or branch, classification, type of imaging study, biopsy result, infection rate, recurrence rate, sequelae, among others, were analyzed.

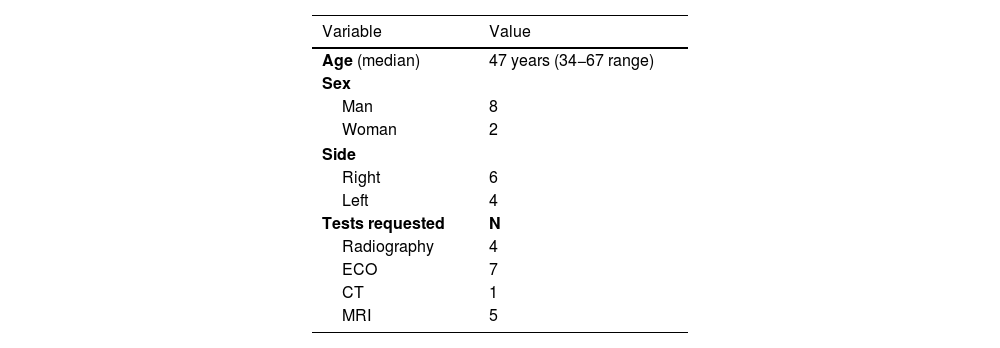

ResultsWe included 8 men and 2 women with an average age of 47 years (range 34−67) and an average follow-up of 62.2 months (range 2–149). All cases were related to intrinsic compression. The most frequent cause was the presence of cyst (40%) followed by perineural adhesions (20%). The posterior tibial nerve was the most affected (50%) and 30% the medial plantar branch. Ultrasound (70%) and MRI (50%) were the most requested studies. There were no cases of postoperative infection. There were 3 patients who presented recurrence of the lesion requiring a new surgery.

ConclusionsTTS is a neuropathy involving the posterior tibial nerve or some of its branches. In general, it is caused by compression of the nerve by different structures such as accessory muscles and ganglions, among others. The diagnosis is eminently clinical, supported by imaging studies. Surgical treatment presents better results when the cause is an intrinsic compression, although variable recurrence rates are described.

Revisión retrospectiva de pacientes con diagnóstico de Síndrome del Túnel del Tarso (STT) tratados quirúrgicamente.

MétodoSerie retrospectiva de pacientes con diagnóstico de STT operados entre los años 2005 y 2020 en un mismo centro. Se analizan variables como edad, sexo, lado, nervio o rama afectada, clasificación, tipo de estudio imagenológico, resultado biopsia, tasa de infección, tasa recurrencia, secuelas, entre otras.

ResultadosSe incluyen 8 hombres y 2 mujeres con edad promedio de 47 años (rango 34–67) y seguimiento promedio de 62,2 meses (rango 2–149). Todos los casos se relacionan a una compresión intrínseca. La causa más frecuente fue la presencia de quiste (40%) seguida de adherencias perineurales (20%). El Nervio Tibial Posterior fue el más afectado (50%) y 30% la Rama Plantar Medial. La Ecografía (70%) y Resonancia Magnética (50%) fueron los estudios más solicitados. No hubo casos de infección postoperatoria. Hubo 3 pacientes que presentaron recurrencia de la lesión requiriendo una nueva cirugía.

ConclusionesEl STT es una neuropatía que compromete al nervio tibial posterior o a algunas de sus ramas. En general su causa es la compresión del nervio por distintas estructuras como músculos accesorios y gangliones entre otros. El diagnóstico es eminentemente clínico apoyándose en estudio por imágenes. El tratamiento quirúrgico presenta mejores resultados cuando la causa es una compresión intrínseca, aunque se describen tasas variables de recurrencia.

Tarsal tunnel syndrome (TTS) is a neuropathy which compromises the posterior tibial nerve (PTN) or some of its branches: the medial plantar branch (MPB); the lateral plantar branch (LPB) and the medial calcaneal branch (MCB). Kopell and Thompson1 described this pathology in 1960 and later in 1962 and 1967, Lam2 and Keck3 ratified its description and characteristics. Regarding pathogenesis, in 60%–80% of cases it is possible to determine aetiology.4–7 In general the cause is nerve compression by structures which include accessory muscles, lipomas, tumours, cysts or ganglions, and bone fragments.6–14

Symptoms for this syndrome vary, with standard presentation being both acute and chronic, characterised by the presence of hypoaesthesia and pain in the sole of the foot, paraesthesias in the distal region of the toes, metatarsals and/or heel. Pain radiating down the back of the leg has also been described, which worsens when standing for long periods of time.15–17 Diagnosis is eminently clinical with support from imaging and/or electrophysiological studies.6,18 Surgical treatment has the best outcomes when the cause is intrinsic compression.18–20 The aim of this study was to present the outcomes and follow-up of a series of patients with TTS who were operated on in our hospital.

Material and methodThis study was approved by our Hospital’s Ethics Committee.

A retrospective series of patients over 18 years of age diagnosed with TTS and operated on between the years 2005 and 2020. Their medical records were reviewed, as were imaging studies, and the results from tests, among others. A total of 10 patients met with the criteria outlined. The group comprised eight men and two women with an average age of 47 years (34−67 range).

Diagnosis of TTS was carried out clinically (medical file, symptoms, and physical examination), supported by imaging and/or electromyography study (EMG). The degree of nerve or nerve branch compression was determined, according to the previously described parameters.

All cases were operated on. Surgery used medial approach to the ankle following the PTN pathway, opening of the flexor retinaculum, identification of the PTN and its branches and also the vascular bundle and flexor tendons. Intraoperative events such as the type of lesion and area of compression were reported. When applicable the result of the histopathological study of the resected tissue was recorded. Clinical and imaging follow-up was performed describing infection rate, recurrence and /or sequelae, when applicable.

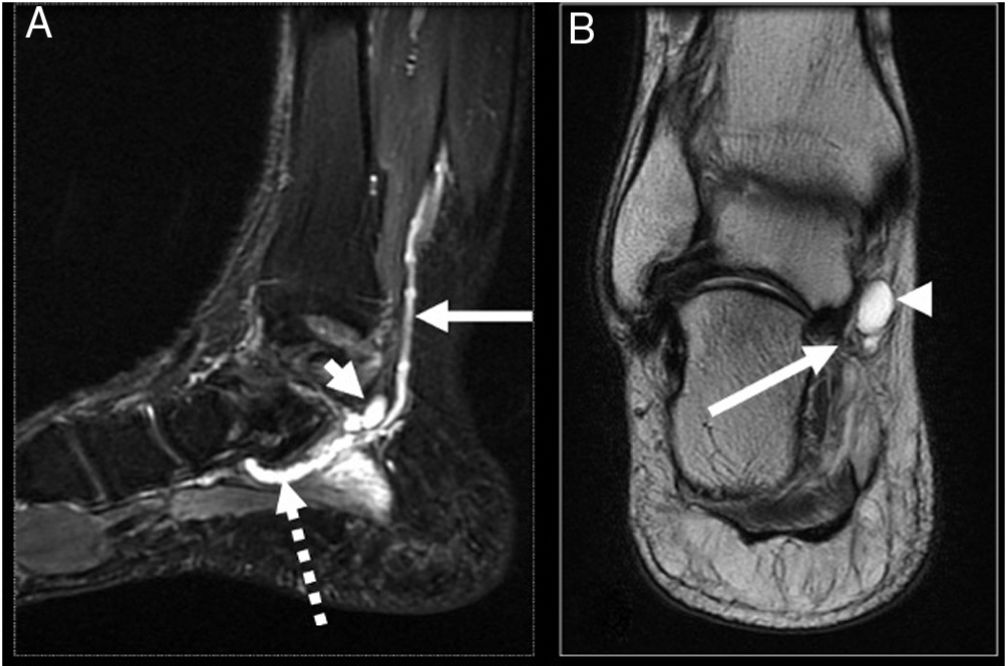

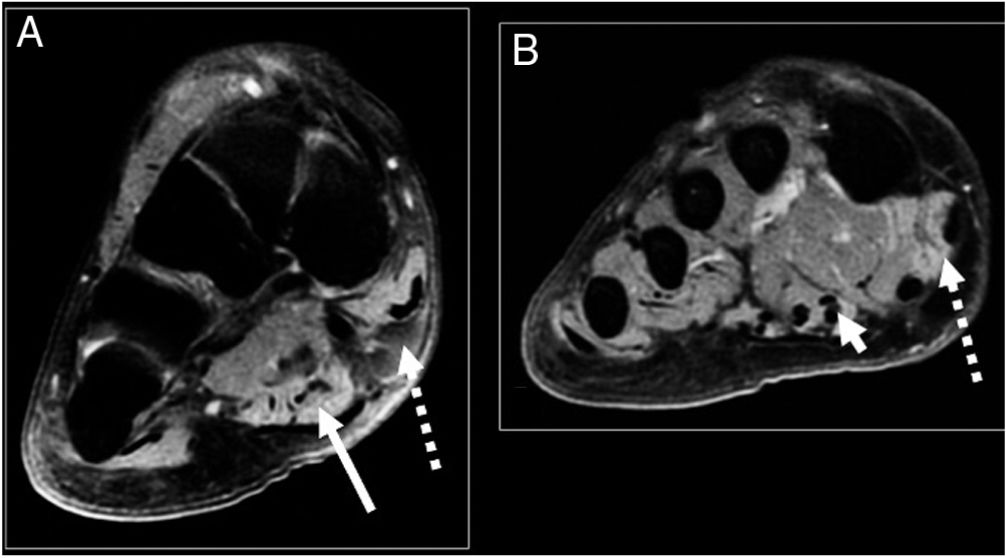

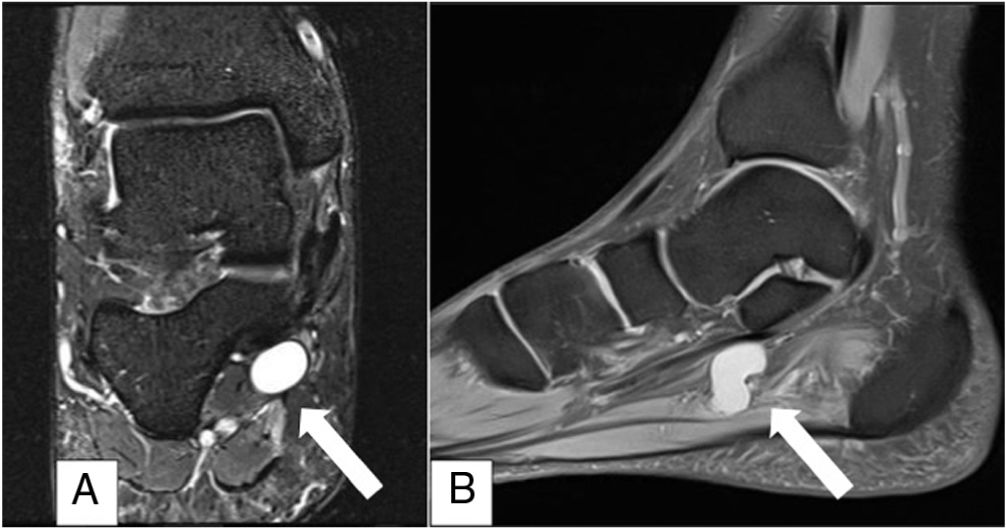

By way of example, we present the case of a healthy 53-year-old male patient, who consulted due to pain in the medial surface of the right ankle of four-month onset, associated with an increase in volume of the area, paraesthesia and hypoaesthesia in the medial sole area of the right foot. Physical examination highlighted the increase in medial inframaleolar volume, sensitive to the touch, Tinel’s sign and hypoaestheisa in both plantar branches major to medial. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (Figs. 1 and 2) showed a round, cystic lesion associated with vascular chordal structures in association with PTN. EMG revealed symptoms compatible with TTS.

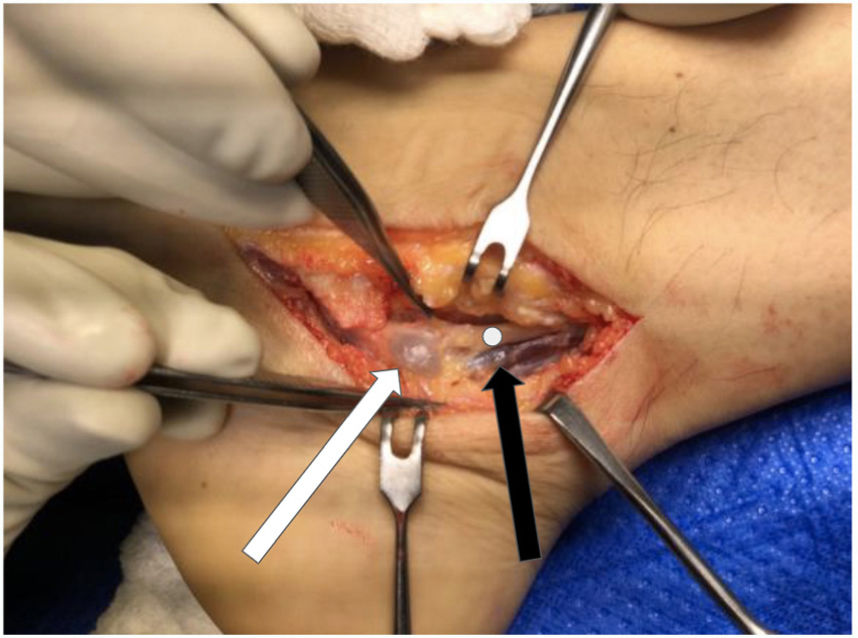

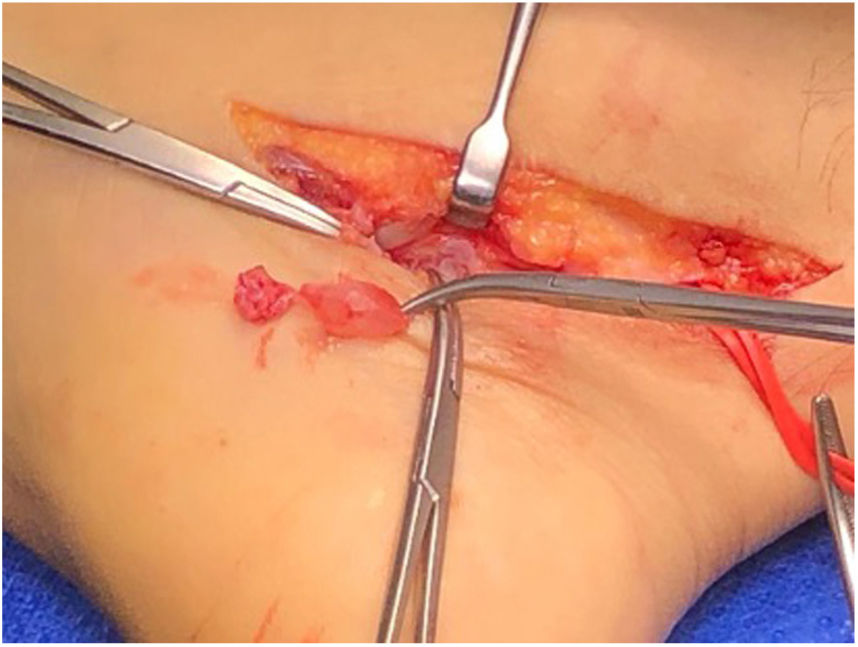

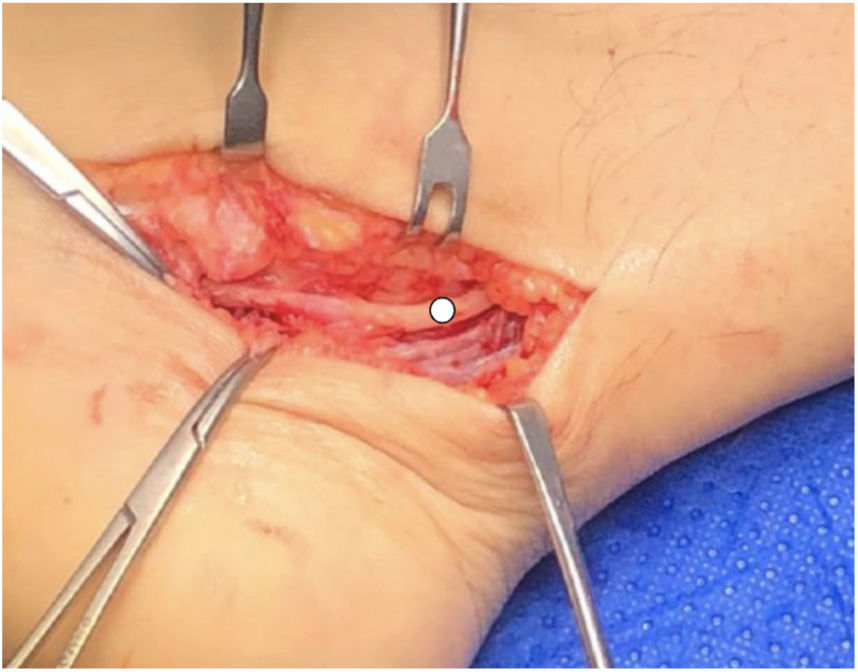

A medial approach was made, following the PTN trajectory. On opening the flexor retiniculum a rounded cystic formation was observed in addition to varicose veins in the area (Fig. 3). The cystic lesion was resected and sent for biopsy, completely releasing PTN and LP and MP branches (Figs. 4 and 5), with no other areas of compression visible. The patient was discharged with an orthopaedic cam boot. The histopathological study was compatible with ganglion.

In total 10 patients were operated on, six with lesions on the right side and four with lesions on the left. The most used imaging studies were echotomography (ECO) (seven cases) and magnetic resonance imaging (five cases) (Table 1). EMG was performed in four cases which showed signs compatible with TTS. With regard to the cause of TTS, four cases were related to the presence of a synovial cyst, two cases to scar adhesions (previous surgery), one to arteritis, one to perineural varicose veins, one to abductor hallux fasciae compression and one to bone fragment. In five cases PTN involvement was observed, two cases of the lateral plantar branch and three cases in the medial plantar nerve. There were no postoperative cases of infection.

In our series, two patients had been previously operated on in another centre, with poor clinical response, one with a diagnosis of plantar fasciitis and the other with left TTS.

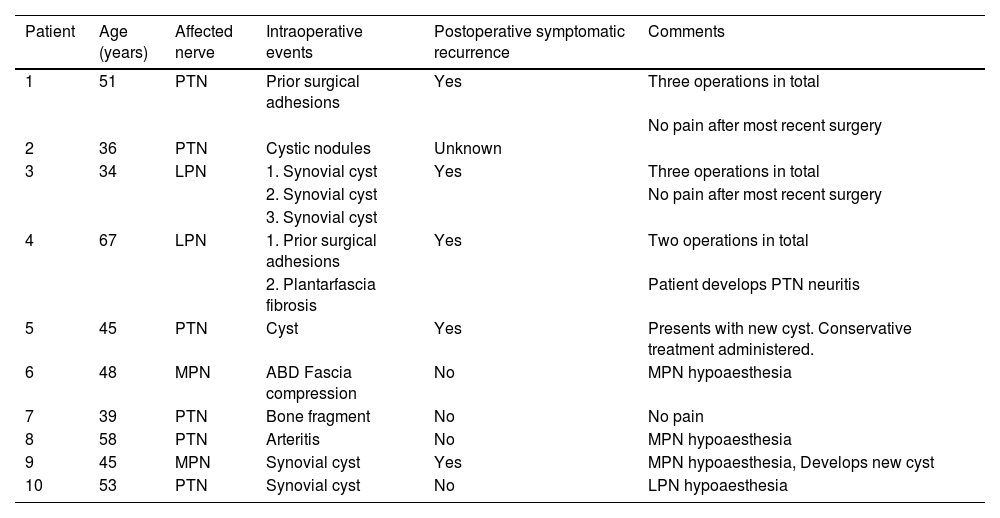

Average follow-up was 63.2 months (2–149 range). At the time of follow-up, five patients presented with a recurrence of operated lesions, 3 of whom required further surgery. On average, subsequent surgery was performed after 3.6 years (6 months-11 years range). Table 2 contains the summary of the operated cases.

Summary of operated cases.

| Patient | Age (years) | Affected nerve | Intraoperative events | Postoperative symptomatic recurrence | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 51 | PTN | Prior surgical adhesions | Yes | Three operations in total |

| No pain after most recent surgery | |||||

| 2 | 36 | PTN | Cystic nodules | Unknown | |

| 3 | 34 | LPN | 1. Synovial cyst | Yes | Three operations in total |

| 2. Synovial cyst | No pain after most recent surgery | ||||

| 3. Synovial cyst | |||||

| 4 | 67 | LPN | 1. Prior surgical adhesions | Yes | Two operations in total |

| 2. Plantarfascia fibrosis | Patient develops PTN neuritis | ||||

| 5 | 45 | PTN | Cyst | Yes | Presents with new cyst. Conservative treatment administered. |

| 6 | 48 | MPN | ABD Fascia compression | No | MPN hypoaesthesia |

| 7 | 39 | PTN | Bone fragment | No | No pain |

| 8 | 58 | PTN | Arteritis | No | MPN hypoaesthesia |

| 9 | 45 | MPN | Synovial cyst | Yes | MPN hypoaesthesia, Develops new cyst |

| 10 | 53 | PTN | Synovial cyst | No | LPN hypoaesthesia |

ABD: hallux abductor; LPN: lateral plantar nerve; MPN: medial plantar nerve; PTN: posterior tibial nerve.

TTS is a neuropathy which compromises the PTN or some of its branches. Its cause is determined in 60%–80% of patients,4–7 and causes are classified as intrinsic or extrinsic,14,18,19 although idiopathic causes have also been described.12,18,21

In our study the feeling of hypoaesthesia combined with variable degrees of plantar pain were the most common reasons for presentation, which is in keeping with that reported in the literature.15–17

TTS treatment may be conservative or surgical.5,14,22 When tunnel occupation is the cause surgical treatment presents with better outcomes, compared with treatment for idiopathic causes.5,14,18–20 Gangliones, lipomas, accessory muscles, fracture sequelae and varicose veins are some of the described lesions which occupy the anatomical space where the PTN or its branches are found, causing the described symptoms.6,14 Schmidt-Hebbel et al.10 presented the case of a patient with TTS provoked by the presence of bilateral flexor digitorum accessorius longus muscle with favourable evolution after its resection. Badr et al.5 described the presence of the accessory soleus muscle as the cause of nerve compression in a patient aged 13 years. In our series, the most frequent cause of compression was the presence of a cyst (four patients). In 1991, in the series by Takakura et al.,12 18 out of 50 operated feet were related to the presence of ganglion. In 1999 Nagaoka and Satou13 published a series of 29 patients operated on for compression associated with ganglion, with an average follow-up of 27.5 months. For their part, in 2003 Sammarco and Chang22 published a series of operated patients, where the most common cause was the presence of perineural scars.

Decompression of the tunnel is associated with varied rates of reduction or resolution of symptoms, with success varying between 44% and 96%.18–20,22 Nagaoka and Satou13 describe excellent results and good results in the 29 feet surgically treated for ganglion. The authors13 describe five cases of lesion relapse, of which one required further surgery. Pfeiffer and Cracchiolo23 reported a 44% success rate following tunnel decompression. In our series, three cases presented with lesion relapse, and it was necessary to perform further surgery on two patients with symptomatic perineural adhesions and on one patient with a new cyst. Kawakatsu et al.9 reported the case of a patient who presented with three types of ganglions in a 12 year follow-up period who underwent surgery on three occasions. Our casuistic is similar: a patient was operated on in 2006 with resected lesion compatible with ganglion. Three years later, they presented again with a further increase in volume, with tarsal tunnel ganglion being diagnosed. Secondary surgery was performed with a further resection of the cyst. The patient evolved favourably until 2019 when they consulted due to symptoms compatible with TTS: Imaging studies revealed a new cyst, this time more distal, in relation to the medial plantar branch (Fig.6) for which the patient required a third operation. Nine months of follow-up after the most recent surgery, the patient has no pain. It is possible that relapses are due to remnant ganglion tissue, in which case, symptomatic lesions redeveloped.

In the review by McSweeney and Cichero,18 the authors highlight that the most common cause of symptom recurrence is an incomplete proximal release, apart from the actual scar of the operated region. Both the flexor retinaculum and the abductor hallux fasciae are stenotic regions which may generate this pathology.24 For this reason, authors such as Hong et al.24 and Heimkes et al.25 recommend release of the abductor fascia as a way of improving the outcomes of patients who have been operated on. In our casuistry during the reported follow-up period, three patients evolved with persistence of MPN hypoaesthesia and 2 LPN hypoaesthesia. One possible reason for this persistence could be incomplete release of the said stenotic points.

This study has several limitations. It is a retrospective review of a short series of cases where not all patients were studied with EMG, and it is therefore not feasible to show possible electrophysiological patterns compatible with TTS. Furthermore, we did not use any clinical evaluation scale for TTS severity, such as that published in the Takakura et al. study.12

ConclusionSurgical treatment of TTS presents better outcomes when the cause is an intrinsic compression, although recurrence rates have been described. Dissection and careful release of the PTN and its branches, together with complete resection of the associated lesion, when applicable, are factors associated with better rates of postoperative success for this pathology.

Level of evidenceLevel of evidence IV.

FinancingThis study did not receive any type of financing.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Please cite this article as: Vargas Gallardo F, Álvarez Gómez D, Bastías Soto C, Henríquez Sazo H, Lagos Sepúlveda L, Vera Salas R, et al. Síndrome del túnel del tarso: análisis clínico-imagenológico de una serie de casos. Rev Esp Cir Ortop Traumatol. 2022;66:22–27.