Improvements in cancer diagnosis and treatment have improved survival. Secondarily, the number of patients who present a vertebral metastasis and the number with some morbidity in relation to these metastases also increase. Vertebral fracture, root compression or spinal cord injury cause a deterioration of their quality of life.

The objective in the treatment of the vertebral metastasis must be the control of pain, maintenance of neurological function and vertebral stability, bearing in mind that in most cases it will be a palliative treatment.

The treatment of these complications needs a multidisciplinary approach, radiologists, interventional radiologists, oncologists and radiation therapists, spine surgeons, but also rehabilitation or pain units. Recent studies show that a multidisciplinary approach of these patients can improve quality of life and even prognosis.

In the present article, a review and reading of the literature on the multidisciplinary management of these patients is carried out.

Las mejoras en el diagnóstico y tratamiento del cáncer han mejorado la supervivencia. Secundariamente también aumenta el número de estos pacientes que presentan una metástasis vertebral y el número con alguna morbilidad en relación con estas metástasis. Fractura vertebral, compresión radicular o lesión medular causan un deterioro de su calidad de vida. El objetivo en el tratamiento de las mismas ha de ser el control del dolor, mantenimiento de la función neurológica y de la estabilidad vertebral, teniendo presente que en muchos casos será un tratamiento paliativo.

El tratamiento de estas complicaciones presenta un enfoque multidisciplinario, radiólogos, radiólogos intervencionistas, oncólogos y radioterapeutas, cirujanos de raquis, pero también Unidad de Rehabilitación o Unidad de Dolor. Recientes trabajos muestran que un enfoque multidisciplinario de estos pacientes puede mejorar la calidad de vida e incluso el pronóstico.

En el presente trabajo se realiza una revisión y lectura de la bibliografía sobre el manejo multidisciplinario de estos pacientes.

In recent years, the survival of cancer patients has increased dramatically due to advances in diagnosis and treatment. Consequently, we are also experiencing an increase in the incidence of metastasis.1

Vertebral metastasis is the most frequent tumour in the spine, and the most frequent bone metastasis, and globally the third most frequent site of metastasis after lung and liver. It is estimated that more than 70% of cancer patients will have a spinal metastasis and that 10–30% of cancer patients will require treatment for spinal metastases.2

Pain is the most common clinical symptom, but in more than 75% of cases other symptoms may occur, such as pathological fractures, bone marrow suppression, radicular compression, or spinal cord injury, the latter occurring in 10–20% of patients with vertebral metastases.3,4

All these complications make the patients’ general condition worse and have a negative impact on prognosis and quality of life.5

We must not forget that the goal of treatment for these patients is still palliative. Our usual objectives are to maintain or improve quality of life, control pain, avoid or improve neurological injury, and to preserve walking ability in particular.6,7

Treatment of these lesions currently requires a multidisciplinary approach, given the various treatment options available. Ablation techniques, augmentation techniques, radiosurgery or stereo-radiotherapy, the improved surgical techniques, or the combination of several of them have led to better control of these lesions, but their indication is difficult, with no clear recommendation or assessment of their outcomes in the current literature.7,8 This has led to the publication of multiple decision-making algorithms for the treatment of these patients.8,9

The aim of the present review will be to examine the different management strategies for vertebral metastases and the evidence on the need for multidisciplinary decision-making committees in patients with vertebral metastases.

MethodWe conducted a literature search in PubMed, Cochrane and Embase, using the terms (spine OR spinal OR vertebral) and (metastases OR tumour OR Neoplasm OR cancer) and (multidisciplinary) and (management) and/or (systematic review).

Assessment of the patientThe parameters to stratify and classify patients, and help us in decision-making are expected patient survival, tumour burden and histology, radiographic assessment – spinal stability, neurological injury. These parameters will determine timing of surgery, adjuvant treatment options, expectations of subsequent recovery, or use of palliative measures.

SurvivalThe estimation of patient survival (SV) is critical in the selection of potential surgical patients, and to determine the surgical technique. Estimation of SV according to clinical parameters has proven to be inaccurate and unreliable.10

Numerous scoring systems have been designed to estimate the predicted SV of these patients, in an attempt to stratify and aid decision-making, but neither the methodology used to develop models, nor the results obtained with them have shown sufficient consistency over time.9,10

In a recent systematic review of 22 studies and 7779 patients, a multivariate study found that the only factors associated with mortality were the aetiology of the primary tumour and general condition, with a high level of evidence.11 In another study, up to 20% of patients had a lower-than-expected SV, and surgery was over-indicated. The absence of adjuvant therapy and the patient's nutritional status12 are other factors associated with poorer survival.

Verlann et al.12 in a multicentre study, with a total of 1266 patients, assessed those with SV of less than three months and those with SV of more than two years. Poor general condition was the single most predictive single prognostic factor for SV, and low tumour burden together with histology of the primary are the most robust prognostic factors related to long-term SV.

A factor that none of the systems address is the patients’ risk/benefit potential with the treatment, in other words, in Verlaan's work,12 most of the patients who died before three months was due to rapid disease progression (85%), this overestimation may be due to the poor calibration capacity of the score or because no system assesses the impact of surgery on the disease (mechanisms of perioperative immunosuppression, surgical stress, blood products that can depress immunity, etc.); thus, SV will be partly affected by surgical aggressiveness.

Oncological status/burdenHistologyThe histology of the primary lesion will inform the patient's prognosis, as it is the single most robust predictor of SV.12,13

StagingThe presence and extent of other metastases has a strong impact on decision-making. Some of the scores assess the number and extent of metastases as a factor related to a decrease in SV (Tomita, Tokuhashi, etc.), however, other studies have not demonstrated this relationship.9–13

Radiographic assessment. Vertebral stabilityRadiographic images must allow us to assess the extent of the lesion, location, canal involvement, and evaluate the instability of the lesion.

There are basically two scenarios. Debut of metastases in a patient with cancer, in which re-staging is mandatory, usually requiring a thoracoabdominal computed tomography (CT) scan and bone scintigraphy, or alternatively a positron emission tomography (PET)-CT scan, looking for other metastases and assessing the need for biopsy to confirm the diagnosis.6

The other scenario is the debut of a lesion in a patient with known metastases. For the actual study of the lesion, we need essentially magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and CT. The radiographic study can be useful primarily when assessing alignment in patients who may require extensive surgery.6,53

MRI has high sensitivity and specificity in detecting metastases (98.5% and 98.7%, respectively).6 It also helps in the differential diagnosis with osteoporotic fractures, which are frequent in oncological patients.6 It will also allow us to assess the severity of cord compression.6,14,22

The CT scan evaluates bone structure and lytic and blastic characteristics of the lesions, degree of cortical involvement, pedicles, or destructive changes affecting the posterior cortex.6,14 It also allows us to quantify the instability of the lesion. In the evaluation of vertebral metastases, sensitivity drops to 66%, whereas reliability is close to 89%.6

In 2010, the Spine Oncology Study Group (SOSG) defined vertebral instability and developed a score to quantify it. A meeting of experts and opinion consensus was used to develop a score to quantify degree of instability, the Spinal Instability Neoplastic Score (SINS).15

It seeks to standardise the assessment of instability depending on the location of the lesion, the type of bone involvement (lytic or blastic), the presence of pain, loss of alignment, and involvement of posterior structures. Each of these factors are categorised and scored from least to most unstable.13–18

The problem is the great lack of definition of the indeterminate instability group, which is the most frequently encountered,16,17 and for whom the best treatment option is still unknown.6,16

Another criticism is its moderate specificity of 79.5%, which means that it fails to identify all true negatives and tends to over-indicate treatment (two out of every 10).18

Radiography has low sensitivity, and therefore beyond its ready availability it should not be used routinely.6

Spinal cord compressionSpinal cord compression and secondary neurological damage are among the most severe complications in cancer patients. Their assessment requires adequate evaluation of walking ability, duration of symptoms, and a thorough assessment of neurological damage and degree of involvement by means of MRI.

Spinal cord injury is directly related to these patients’ health-related quality of life (HRQoL) and also to survival, with clear evidence of greater survival in patients who maintain the ability to walk.19

Progression time of the lesion, loss of walking ability, impaired sphincter control, and muscle pair strength (Medical Research Council strength<III) appear to be the prognostic factors associated with functional recovery.19,20

The degree of spinal cord injury must be assessed according to the neurological classification standards for spinal cord injury, as per the standards of the American Spinal Injury Association (ASIA), which have been updated.21 They have demonstrated high sensitivity and validity, however, due to their complexity these patients may require a rehabilitation physician or neurologist who is familiar with their examination.

Bilsky et al. defined and described an attempt at MRI quantification of degree of tumour compression, and extension. They defined grade 0 and 1, where there is no compression or displacement of the cord, grade 2, where there is displacement of the cord to varying degrees, and grade 3 where the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) signal is lost around the cord.22

Treatment optionsPain control, maintenance or recovery of function, especially neurological function, should be our goals, bearing in mind that these will often be palliative measures. Another scenario is in oligometastatic patients with effective systemic treatment options. In the different scenarios, the aggressiveness and morbidity of treatment must be adapted to the individual patient.3,6,7

Radiotherapy treatmentThis is still the mainstay of treatmentConventional radiotherapy with fractionated doses of 20 or 30Gy has been used for decades, with the limit of 30Gy being the margin of tolerance of the marrow to irradiation; in radiosensitive tumours (haematological or small cell tumours) it has proved effective, other tumours show varying degrees of sensitivity (ovarian, breast, prostate) and generally suboptimal results in other tumours (renal, thyroid, or non-small cell, among others).6,23 Radiosensitive tumours, with pain, without signs of fracture and with minimal epidural component would be ideal candidates (in cases of very sensitive tumours, they also respond effectively in cases of peridural mass).6,53 It is also palliative treatment for pain control in patients with a short life expectancy. It should be remembered that radiotherapy does not control pain secondary to instability or fracture.

The emergence of stereotactic radiotherapy techniques has changed the paradigm between radiosensitive or radioresistant tumours, as a result of technological advances in image guidance and treatment delivery techniques that allow the delivery of large doses to tumours with small margins with high off-target gradients. Stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT) enables dose escalation and increased safety.23 Tumours considered to be radioresistant, such as renal tumours, can now benefit from this treatment, including re-irradiating patients who have been previously treated with conventional radiotherapy.6

A study by Sahgal et al. recently reported the superiority of SBRT at 12Gy/2 fractions vs. conventional treatment of 20Gy/5 fractions for pain control at three and six months, without increased toxicity in patients with oligo- and polymetastatic vertebral metastases.24

Variability in target delineation should no longer be controversial following international expert consensus publications on target delineation, in SBRT scenarios after separation surgery and in SBRT-only treatments.24

It is important to assess the degree of compression to determine the efficacy of SBRT in the management of metastases. Thus, a Bilsky score of 0 or 1 where there is no cord displacement can be treated perfectly well with SBRT, while in cases with a score of 2 or 3 generally require prior surgery to decompress and provide space between the cord and metastatic remnants before SBRT,22,26 known as the separation technique.22–25

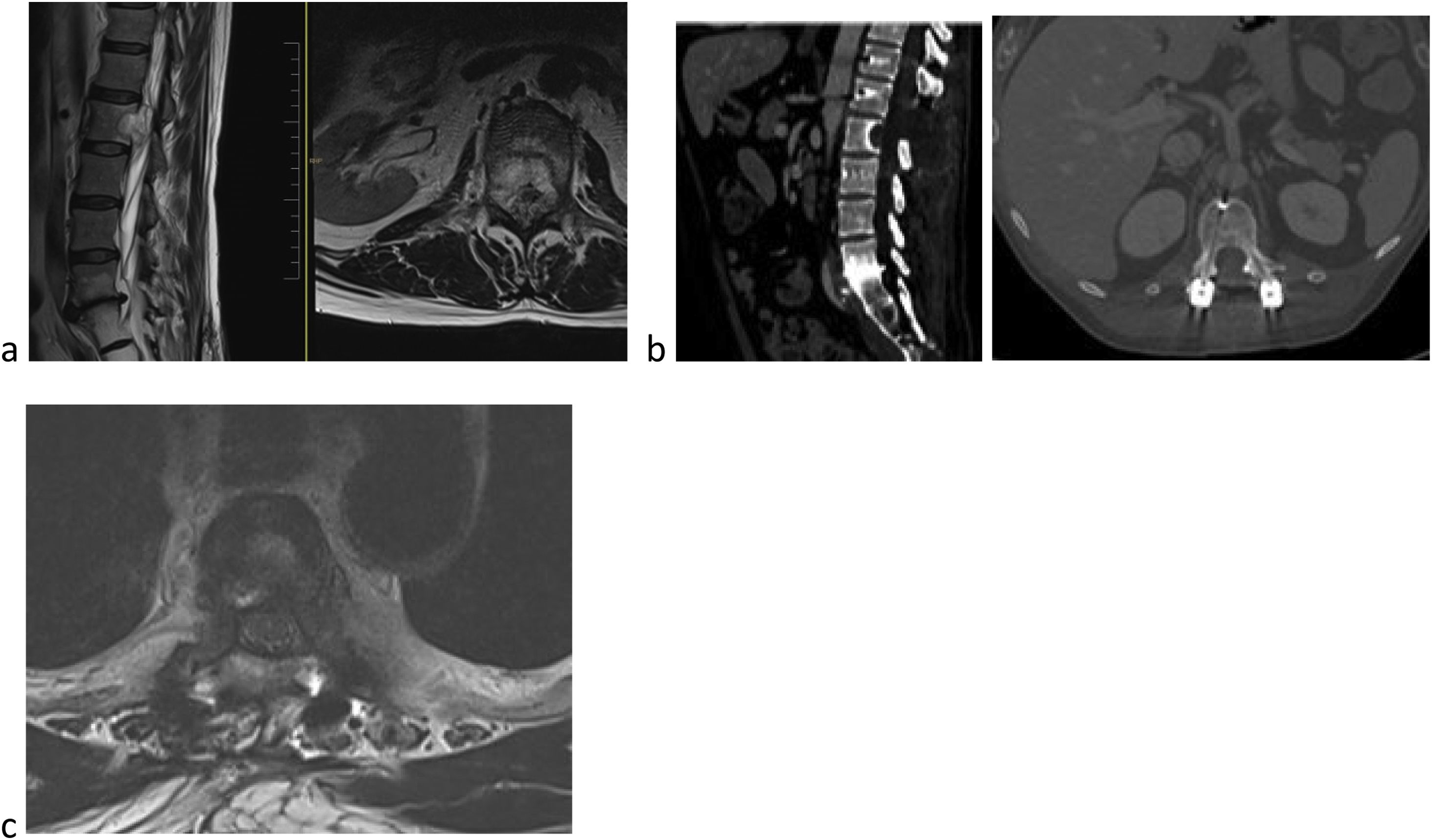

The ideal indication for SBRT would be a patient with partial canal occupation; radioresistant histology, no mechanical instability, and expected SV of more than six months (Fig. 1).

59-Year-old male. L2 body metastasis Tokuhashi 13, SINS 6, and Bilsky 2. (a) This patient has good general condition (GGC) and predicted survival of longer than 12 months. (b) Treatment is decided as partial excision and separation surgery and then SBRT. (c) To optimise preparation for SBRT, carbon fibre instrumentation is decided.

Improved anaesthetic techniques, neurophysiological control, and improved surgical techniques mean we can perform safer and more aggressive interventions, and other mini-invasive interventions with improved results and reduced morbidity.8

Surgery will usually aim to provide stability or decompress the spinal cord, to improve pain, maintain walking ability, and achieve local control.8,27

The results in terms of pain control and improved stability are widely reported in the literature and go beyond the scope of this article.7,8,27,28

The complication rate is 20%/30%,27–29 directly related to the aggressiveness of surgery; therefore, the risk of surgical treatment must always be balanced against the benefit when deciding the surgical tactic/technique to use.

The classical surgical options available to us are palliative decompression, mechanical stabilisation, debulking, and vertebrectomy (piecemeal or en bloc), and more recently, the combination of these techniques for separation surgery and subsequent SBRT.25,26 More evidence is needed to define the role and indication for the different surgical options.7,30

The emergence and development of minimally invasive spine surgery (MISS) techniques seek to change this paradigm.

A systematic review of nine articles compared MISS techniques with open techniques retrospectively (183 vs. 161 patients). These were short, non-randomised series with case selection bias, in which they can only conclude, with little evidence, that MISS techniques can be an alternative to open techniques, with similar results in terms of pain control and local control, without demonstrating other differences due to the heterogeneity of the MISS techniques compared. The supposed improvements in surgical times, blood loss, or reduced hospitalisation are not homogeneous in the nine studies reviewed.31

Lu et al.32 did perform a meta-analysis of only six studies, but only managed to find differences in blood loss and transfusion in favour of MISS techniques, finding no differences in terms of pain, neurological outcome, or operative time and complications.

Other mini-invasive techniques such as augmentation techniques (kyphoplasty or vertebroplasty) have been shown to be effective in pain control for lytic lesions and fractures.8,32,33 Other techniques such as radiofrequency ablation, alone or in combination with augmentation techniques, are showing encouraging results with improved pain, reduced surgical risks, reduced incidence of fractures, and improved quality of life.34

Non-surgical treatmentsPainOral analgesia is considered the first-line treatment for bone pain by the World Health Organisation (WHO). Morphine or derivatives are the most common option for the treatment of severe pain in these patients, but side effects sometimes limit their use.8

The WHO analgesic ladder definition of the fourth step and the availability of the intrathecal or epidural technique have been gaining in popularity, because they have demonstrated better pain control, with lower doses. Improvement in the technique has also decreased its disadvantages such as risks of infection, cost, or durability, with programmable external pumps or subcutaneous implants.35,36

RehabilitationRehabilitation is a crucial factor in the care of patients with vertebral metastases, both for their correct assessment19–21 and for their functional recovery if neurological damage appears.7 It has demonstrated an advantage in the prevention of complications, improvement of functionality, reduction of pain, and improvement of quality of life.37

DiscussionDifferent specialties such as oncologists, radiation oncologists, radiologists and interventional radiologists, rehabilitation specialists, pain units, palliative care and, of course, spinal surgeons are involved in the management of spinal metastases. The assessment and management of these patients sometimes requires complex decision making, where speed in decision making, examinations or necessary interventions is vital to improve the prognosis and quality of life of these patients.38

In many centres, the management of these patients is fragmented, where patients are referred to a number of specialists, with little continuity of care and consequent psychological stress.38

In other fields of spine surgery, such as adult deformity or high-risk surgeries, making surgical decisions in multidisciplinary groups has been shown to be effective and to reduce complications.39

In a recent systematic literature review, Farhadi et al. conducted a systematic review of the literature of studies that include multidisciplinary groups in surgical decision-making in spine pathology. They show a 51% reduction in complications in the first 30 days in adult scoliosis surgery, and between 0% and 14% in complications in other spine pathologies. They conclude that these multidisciplinary groups have an impact on the management of these patients, improve communication between specialties, standardise treatment and improve patient care, although they warn that studies are still lacking to demonstrate that they improve results.40

The management and treatment of spinal tumours pose a challenge due to the inherent complexity of the spine, requiring large resources and time, and where multidisciplinary committees have demonstrated their efficacy.41

Mann et al.41 present their experience in their multidisciplinary spinal tumour committee from 2006 to 2021, where 40% were metastatic, and conclude that it is critical to access multidisciplinary input, increase confidence in decisions for patients as well as physicians and surgeons, assist with orchestration of care, and improve the quality of care for patients with spinal tumours.

These multidisciplinary committees have had a much longer presence in the field of oncology. Since Calman-Hine in 1995 showed a positive correlation between multidisciplinary management and optimal decision-making in cancer patients, multidisciplinary groups and meetings or committees have become the standard in the management of cancer patients.42

Multidisciplinary committee management of cancer patients has been implemented and has become the standard in recent years.43,44

This has improved the preoperative staging of these patients, shortened the time between diagnosis and treatment, made neo and adjuvant treatment more likely. There are changes in diagnosis and prognosis in between 4% and 50% of patients after management by multidisciplinary teams and, overall, this has improved survival and has improved adherence to treatment guidelines.

Decision-making in the treatment of bone metastases was generally not assessed in any committee and it was the oncologist who consulted the spine unit when any complication appeared. Just as oncological treatment options have changed and expanded greatly in recent years, the management of metastases and the different treatment options have also become much more complicated. As we have seen previously, decision making involves assessing general condition, the aggressiveness of the tumour, neurological status, as well as previous treatments received, and the potential systemic treatment options. The impact that this systemic treatment may have on the metastasis to be treated also must be assessed. In addition, the impact that delay in initiating systemic treatment may have on overall SV must be assessed, bearing in mind that in most of our cases management will be palliative, as mentioned above. All this makes it all the more advisable to assess these patients in multidisciplinary teams, especially given the wide range of clinical presentations or primary tumours, some of which are rare, and therefore it is difficult to gain experience without centralised decision-making and management.41,45,51

Using multidisciplinary committees for the management and treatment of vertebral metastases has shown an improvement in the speed and initiation of treatment, greater prevention of “spinal events”, and a decrease in emergency surgery for spinal cord compression.41,46,47

Hence, in this Japanese group, all spinal metastases are reported by radiologists and those with a SINS>7 are presented to a committee, thus avoiding, or improving the medical delay that occurs in many cases when oncologists are those who report spinal complications and do not always adequately assess the risk signs.48

The objective of a committee for vertebral metastases would be to improve their diagnosis and assessment, to anticipate and prevent their associated complications, and to provide quicker and more effective treatment in cases where they occur, enabling coordinated, rapid, and adapted intervention with the aim of maintaining the patient's quality of life.45,51

Committees have also been shown to change palliative treatments and extend survival in terminal cases. It has also been shown that a failure to implement best clinical practice, associated with not implementing or having access to committees, has resulted in 50,000–100,000 avoidable deaths in Europe.49–51

There is still much work to be done, such as convincing oncologists of the need for and importance of the management of bone metastases, particularly vertebral metastases. A typical complaint from the surgical team is the delay in consulting us. Bone metastases were generally not thought to be associated with prognosis, and therefore many patients were referred to us only when they presented with a complication.

There are studies that show that delay in consulting the surgical team is an independent predictor of worse prognosis,52 and a reason for more aggressive surgery.

There are many possible reasons for this delay, one of which is the accepted criteria used to monitor the progress of cancer patients. These are reflected in the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumours (RECIST) 1.1,53 a set of published guidelines for assessing tumour extent to give an objective value on the response of a tumour to therapy, and thus categorise the tumour as remission, partial response, stable, or progressive disease. Metastases are divided into target lesions (those that are measurable) and non-target lesions (those that are not measurable), which includes vertebral metastases. For disease to be deemed progressive, non-target lesions are only considered if they worsen sufficiently dramatically that the status of the target lesions does not matter,53 therefore non-target lesions are not usually assessed in cancer response studies unless there is significant progression.

Our groupMeetings must be held regularly; in our case they are held weekly. A doctor must coordinate the meeting. The objectives are to confirm diagnosis, determine general condition, and expected vital prognosis, indication of radiotherapy vs. surgery or combined, and in these cases to plan the time between surgery and SBRT, and adjust the timing of necessary complementary explorations, timing/delay in administering systemic treatment, interventional radiological indication, orthosis, or rehabilitation requirements.54

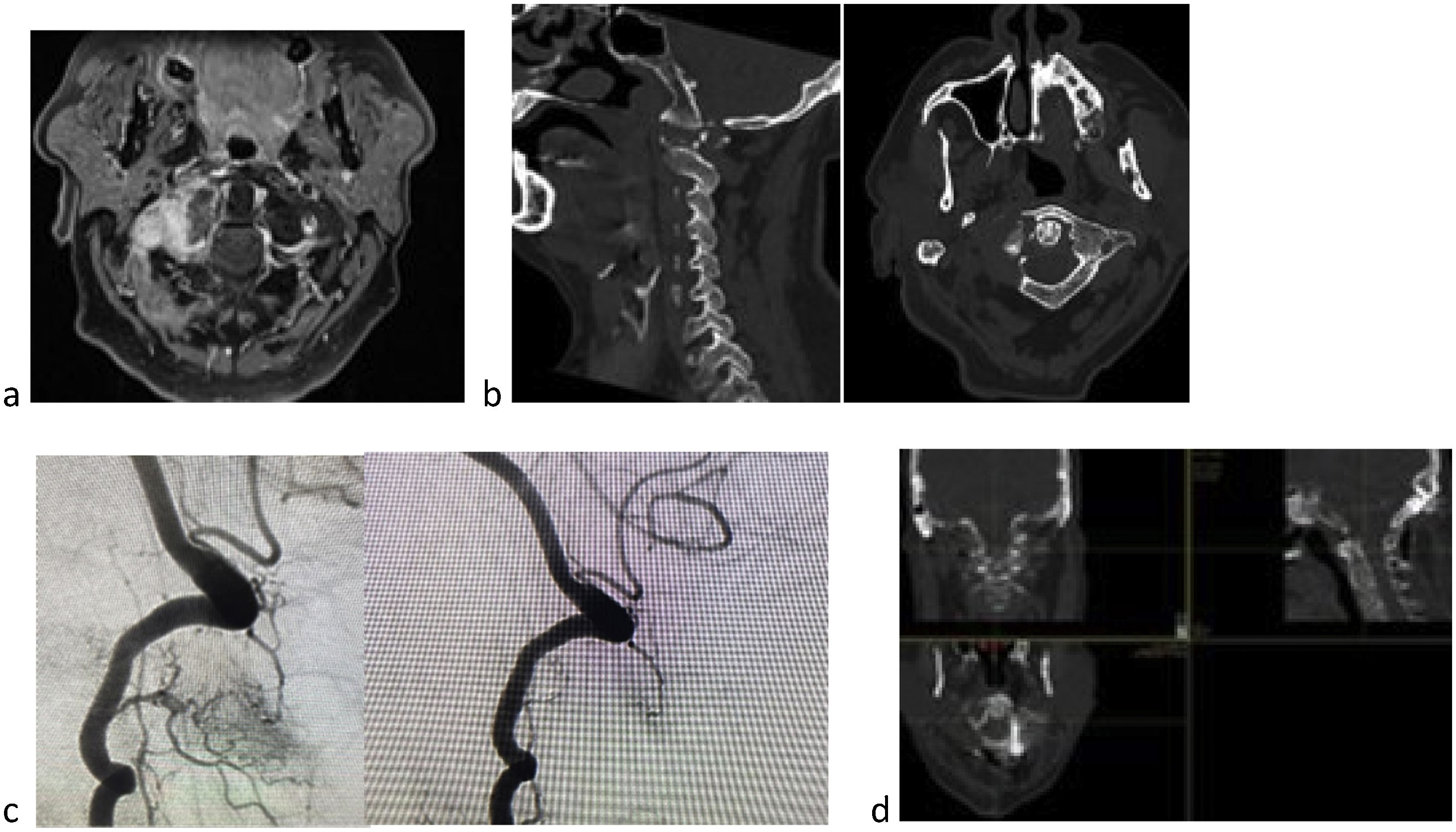

The committee is made up of several members of the spine unit, one acting as chairman of the committee and coordinator of the meeting, radiology members, locomotor system and nervous system resonance experts, two radiotherapy members, several medical oncology members, usually from genitourinary, oncohaematology, and breast units, and depending on the primary tumour, members from the different units, an interventional radiology member (who in our centre also performs augmentation techniques) (Fig. 2), two rehabilitation staff from the spinal cord injury unit. And then, depending on the needs of the case, members of the pain unit and members of vascular interventional radiology may be included.

60-Year-old male with clear cell renal carcinoma. Lateral mass metastasis of C1 (a), with pain, pathological fracture (b), and altered gaze axis. Tokuhashi 7, SINS 13 (b), and Bilsky 1a. This is an unstable lesion, in a patient with an expected survival of less than six months if we follow the Tokuhashi score, but with autoimmune treatment options by oncology and expected survival of more than 18 months, stabilisation and SBRT is decided. Due to the predicted survival, partial excision was decided to reduce tumour burden and optimise SBRT (d). Because this is a hypervascular tumour prior embolisation is recommended, despite the risk of spinal cord ischaemia in this location (c).

Meetings take place on a weekly basis and doubtful cases are presented. Other cases, where there is less doubt regarding indication or treatment, and urgent cases are assessed through interconsultations or a multidisciplinary telephone group. We use a common language, vertebral instability is assessed by SINS; the degree of radiological compression according to Bilsky (both by radiologists, SINS without considering the presence of pain, which is discussed in committee); neurological injury is assessed by the spinal cord injury team and expected SV is discussed with the oncologist in terms of potential treatment options or lines and general condition, and the expected response of the patient combined with the Tokuhashi score (Table 1).

Descriptive table of the patients discussed in committee during 2021.

| Patients discussed at the vertebral metastases committee 2021 | 122 cases |

|---|---|

| Age | 61 years (27–88) |

| Sex | 67 females |

| Primary tumour type | 122 cases discussed |

| Breast | 38 (31.1%) |

| Lung | 13 (10.6%) |

| Prostate | 11 (9.0%) |

| Colon | 10 (8.1%) |

| Urogenital | 8 (6.5%) |

| Multiple myeloma | 8 (6.5%) |

| Other primary | 34 (27.8%) |

| Surgical treatment | 24 cases |

| Survival | 19 patients>year (79.1%) |

| 3 patients<6m (12.5%) | |

| 2 patients<3m (8.3%) | |

| SINS | |

| Stable (0–6) | 2 cases (7.6%) |

| Indeterminate (7–12) | 16 cases (69.3%) |

| Unstable (13–18) | 6 cases (23%) |

| Preop VAS preop (mean, SD) | 5.6 (SD 2.4) |

| VAS at 3 m (mean, SD) | 3 (2.4) |

| Previous ASIA | |

| E | 10 (41.6%) |

| D | 12 (50%) |

| C | 2 (8.3%) |

| ASIA at 3 m | |

| E | 14 (60%) |

| D | 5 (20.8%) |

| C | 1 (4.2%) |

| Unknown | 2 (8.3%) |

| Exitus | 2 (8.3%) |

In the group of surgical patients, we do not consider those undergoing augmentation or ablation techniques and/or combined with RT. Only patients operated on by the spine unit.

ASIA: American Spinal Injury Association; VAS: Visual Analogue Scale.

Vertebral metastases can cause serious complications in frail patients such as those with cancer.

Improvements in treatment, both systemic and local, have greatly opened up the treatment possibilities for these patients, which has made decision-making complex.

Although there are various algorithms that can guide us in decision-making, all these models have proven imprecise, and therefore individualised assessment and indication is recommended.

Joint discussion and decision-making in these complex cases improves treatment for these patients, but it has yet to be demonstrated that it improves SV.

Level of evidenceLevel of evidence iii.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

FundingThe authors declare that they have received no funding for the conduct of the present research, the preparation of the article, or its publication.