Removal of cement and especially the distal cement plug during cemented arthroplasty replacements is key to the success of the surgery, but can be challenging for the surgeon. The methods employed for this step can be very varied, ranging from removal with the aid of rasps, drills, ultrasonic techniques, to bone windows for direct access to the plug. These techniques can sometimes lead to perforation of the bone cortex and even to the production of uncontrolled fractures that prevent safe implantation of the new implant.

The aim of this study is to review the different cement removal techniques and to evaluate the efficacy of a new technique, which allows the cement plug to be removed in a safe and controlled manner, avoiding the need for osteotomies. A customised guide is used for this purpose. This allows an effective and leak-free re-cementing of the new implants.

We present 3 cases of distal cement removal using a customised guide that allows the cement plug to be broached. In all 3 cases, after cement removal, the implantation of longer stems with correct cementation was achieved.

It should be noted that the target population in all cases is an elderly Spanish population, a population of short stature with curved femurs and poor bone quality; these characteristics make perforation and intraoperative fractures much more likely. However, in our two patients there were no cortical perforations. The mean time for plug removal was 22min.

ConclusionThe use of customised guides for cement plug removal during cemented hip and knee arthroplasty replacement is safe and effective.

La retirada del cemento y especialmente del tapón distal de cemento durante el recambio de artroplastias cementadas es clave para el éxito de la cirugía, pero puede ser un reto para el cirujano. Los métodos empleados para este paso pueden ser muy variados, desde la extracción con ayuda de escoplos, brocas, técnicas de ultrasonidos hasta la realización de ventanas óseas para acceso directo al tapón. Estas técnicas pueden llevar, en algunas ocasiones, a la perforación de la cortical ósea e incluso a la producción de fracturas descontroladas que impidan la implantación segura del nuevo implante.

El objetivo de este estudio es revisar las diferentes técnicas de extracción de cemento y evaluar la eficacia de una nueva técnica, que permite la retirada del tapón de cemento de manera segura y controlada, evitando la realización de osteotomías, usando para ello una guía personalizada, lo que permite una nueva cementación efectiva y sin fugas de los nuevos implantes.

Presentamos tres casos de retirada de cemento distal empleando una guía personalizada que permite brocar el tapón de cemento. En los tres casos se consiguió, tras la retirada del cemento, la implantación de vástagos más largos con una correcta cementación.

Cabe destacar que la población diana es en todos los casos población anciana española, de baja estatura con fémures curvos y mala calidad ósea; estas características hacen mucho más probable la perforación y fracturas intraoperatorias. No obstante, en nuestros dos pacientes no hubo perforaciones de cortical. El tiempo medio de retirada del tapón fue de 22 minutos.

ConclusiónEl uso de guías personalizadas para la retirada de tapón de cemento durante el recambio de artroplastia de cadera y rodilla cementada es seguro y eficaz.

Life expectancy in our environment is increasing, with the subsequent growing frequency in our regular practice of cemented knee and hip revision arthroplasties in patients who are increasingly older and with poorer bone quality.1–3 New implants to be implanted often require longer stems, which makes it imperative to remove the cement plug, and occasionally plastic plugs. This may be difficult to achieve, particularly when the plug is highly interdigitated into the bone or when it is highly distal. If these manoeuvres are complex in hip replacement surgery, they are all the more so in knee replacement exchanges, due to the narrow diameter of the tibia and the close relationship between the cement plug and the bone cortex.

Many different techniques have been developed for this, but all of them carry the risk of cortex perforation and intraoperative fractures. It has been estimated that the risk of these fractures ranges between 6% and 50%.4,5

Cement plug removal techniquesOpening the cortical window at the height of the cement plug so as to be able to extract it through this window. This option may appear simple but in our experience takes longer than expected on occasions, either because the size of the window was not correctly chosen or it has to be redone or because the plug is closely attached to the bone and despite being able to view it directly, extraction requires meticulous work with rasps to undo the join. Furthermore, this window has to be replaced and fixed with osteosynthesis such as circlage wires, because if not the cementation of the new implant would be defective.6

Specific rasps for cement removal (Depuy-Synthes®Moreland type rasps) allow for simple removal of the surrounding cement but not the distal cement. The latter breaks up into many pieces, the removal of which is complex and not exempt from the risk of false pathways despite the use of radioscopy during extraction. Due to the prolonged and frustrating nature of this technique it may on occasions lead to the exhaustion of the surgical team.

Hands-free circular drills are effective in wide canals (such as in the femur) but not so much in narrow ones. The small size of the drills tends to eat away at the bone which presents less resistance than the cement, such as for example in tibias with narrow canals, a common occurrence in our population.

On occasions a distal cement drill is also used. This is centred with the help of radioscopy and once broaching through this orifice has been achieved with a Küntscher guide the drilling of the cement plug may progressively be undertaken. Since the drills have not been designed for this job they do not effectively remove the cement and if the guide has not been centred well, if the drill comes into contact with bone, it always tend to eat way at the bone making perforations in the cortex.

Technique using ultrasound to break the bone cement interface and later extract the cement with the help of clamps and rasps, possibly even under direct endoscopic vision (Orthofix® Oscar 3De). Probes activated by ultrasounds are used and these convert the electric energy into mechanical energy producing a dynamic tension, i.e. vibrations in the bone which, together with an increase in local temperature, softens the cement bone union. This temperature may reach 2000°C at a distance of 1mm, which may lead to thermal damage in the underlying tissue. This technique is not available in certain centres due to its high price, and in some countries it even remains unsold.

Extraction through specific cementation techniques such as A2C Cemover® which, after introducing a modular metallic rod through the cement plug, cements the whole space and after polymerisation of this it is extracted by means of backward hammer blows which enable the new and old cement to be removed with the old cement adhering with greater force to the new than to the bone. In our experience we have had several different complications: dissociation between the metallic rod and the new cement, lack of union between the new and the old cement, removal of not just the old cement but also the residual bone in poor quality bones.7,8

Distal cement drilling techniques have also been published where metallic centring devices of several sizes are used to avoid cortical perforations.9 However, we have never been able to procure these centring devices.

Several authors recommend the use of medical imaging management software to increase precision in bone cement removal and thereby reduce periprosthetic fracture rates.10

In our centre we have developed a novel technique with the help of 3D printing which as far as we are aware has never to date been described.

Material and methodWe selected three cases with the diagnosis of aseptic displacement of cemented components. In all cases diagnosis was made using plain X-ray and computerised axial tomography (CAT) with cuts of 1mm, in addition to a laboratory study where leukocytosis and inflammatory markers (erythrocyte sedimentation rate, reactive C protein and fibrinogen) which would indicate infectious processes were ruled out. The need for removal of implants was determined and for the replacement of longer ones, which necessitated having to extract the distal cement (cement plug). To undertake extraction of the distal cement we created an external guide that was adapted to the specific anatomy of each patient which guided us to the centre of the cement plug without error, either in the tibia or the femur. The guide was designed from an updated CAT scan with 1mm cuts which included the entire bone from which the cement was to be extracted, by a company specialising in 3D printing (Kuneimplants®). The design was created in the negative of the most characteristic bone ridges of the patient through a coordinated work flow between our clinical experience and the experience of the engineers who designed the template.11 The guide included a prolongation directed at the centre of the plug (Fig. 1).

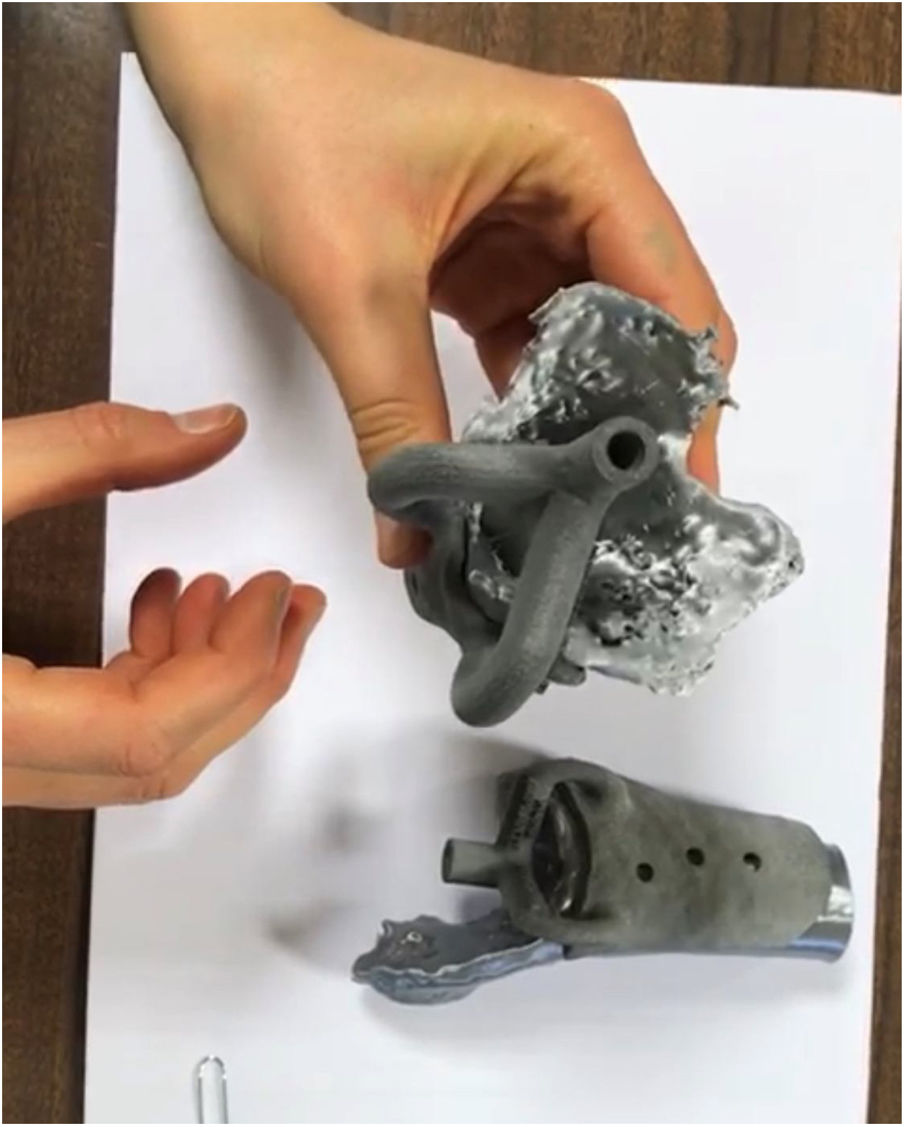

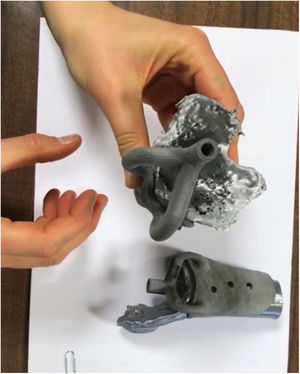

Once the design had been made, the guide was printed in polymethylmethacrylate (PLA) with the help of a domestic 3D printer (Ultimaker®). Also, prior to surgery, we printed out the patient's bone to confirm that the guide perfectly adapted to the bone and guided us to the desired site, simulating the surgical cement plug broaching (Fig. 2). These guides were sterilised at a low temperature in peroxide, although they could also have been sterilised with ethylene oxide.

During surgery we carefully exposed the bone ridges necessary to apply the 3D guide; we removed part of the cement with rasps in the standard way up to the plug. Once there, we applied the guides which are fixed with two 4.5 monocortical screws and we introduced a 5mm drill through this, confirming under fluoroscopic guidance that the drill was concentric. We then proceeded to progressively drill with increasingly larger drill heads or circular drills. In the tibia we used a drill up to 9mm and in the femur up to 10mm (Fig. 3). This drilling does not seek to remove all cement (which would be necessary in the case of septic exchanges) but to make enough space for the implanting of the new, longer stem.

ResultsWe performed this technique in two patients. In one of them to remove the cement plug in the femur and a cement plug in the tibia to then implant a rotating hinged model knee replacement (Waldemar Link® Endo model) with stems of 200 and 160, respectively. In the second patient we removed the cement plug of the femur to exchange an Exeter stem (Stryker®) which had been displaced for another longer one (Fig. 4).

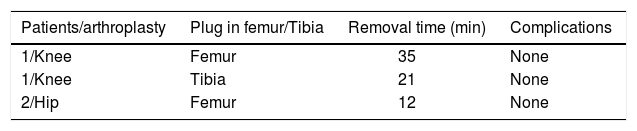

Mean duration of plug removal was 23min in the femur and 21min in the tibia. No complications arose and it was possible to subsequently cement a new implant correctly (Table 1). With this technique not only did we open an intramedulllar space for the prosthetic exchange, but in both cases the time in surgery necessary for standard plug removal with the previously described techniques was reduced. Moreover, the plastic obturator plug was extracted enrolled in the drill in both cases (Fig. 5).

The removal of cement during cemented arthroplasty exchange is essential for new prosthetic implantation. The standard method consists of attacking the bone cement interface with rasps, once the prosthesis has been removed, leading to the cement becoming separated from the bone in fragments and these are removed with the help of forceps. The deeper they are in the bone canal the more difficult interface viewing is and control over the direction of the rasp may therefore be lost. This may all lead to false pathways and intraoperative fractures.4,5,12,13 The technique we describe seems to largely avoid these complications, since the drill or mill we use is always guided and controlled by the guide which is firmly attached with 4.5 screws and in our group we had no complications of this type.

Another disadvantage of cement removal is the time required for it. Several studies have estimated this time to be between 25 and 50min.14 In our case the mean time of cement removal was 22min, which is considerably lower. Reduction of cement extraction time is a key factor, because firstly it means total time in the operating theatre is reduced, thereby lowering the high risk of infection and it also means the surgical team is not so fatigued when implanting the final prosthesis, avoiding errors at this stage.

It is also possible that the cement plug may not finally be extracted with standard techniques.7 This would force the surgeon to use a shaft that was the same or shorter than that used previously and this could compromise the final outcome of the new arthroplasty. In our series, albeit short, no cases with these characteristics occurred.

Another definite advantage of using a specific guide for access to the cement plug is avoiding the use of osteotomies for cement removal. These osteotomies necessitate wider approaches being used, which increase bleeding and the risk of infection and also enforce the use of osteosynthesis materials to ensure consolidation in a good osteotomy position. They also greatly complicate prosthetic reimplantation as cement leaks are likely.15

Using customised guides is economical and is usually rapid. They may be applied as in our case by a specialised medical 3D print but it is possible in some centres to do this without external aid. Several studies have been published on the efficacy of guides using domestic 3D printing, making it even more economical.11 It is worth remembering that the guides should be designed bearing in mind that the material should not buckle/fold during its use, since high precision is a requisite. For this reason we will always use a robust and solid design. One limitation regarding the use of customised guides is that they produce additional fractures in the bone on which the guide is positioned during surgery. In fact, exposing the bone surface over which we will fix our guide, if care is not taken, can lead to bone losses, which reduces the precision of our 3D template and may even make its use unviable.

To date no study has been made as to whether the bone exposure required for fixing the guide may slow down surgery, increase blood loss or risk of infection. In our short experience we did not find dissection was excessive compared with other implant exchanges, and total time in the operating theatre was lower than usual.

In consideration of all of the above, we believe that this cement extraction technique is promising and may lead to changes in cement extraction, which orthopaedic surgeons are so wary of.

ConclusionThe extraction of cement guided by customised and printed templates with the help of 3D technology offers an attractive alternative to standard manual cement plug removal. It is efficient and safe but further studies are required here to clarify whether the use of customised guides is truly useful for the extraction of bone cement plugs.

Level of evidenceLevel of evidence IV.

FundingThis study received no type of funding.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Crego Vita DM, Aedo Martín D, Martín Herrero A, García Cañas R, Areta Jiménez FJ. Una nueva técnica para la retirada del tapón de cemento en recambios de artroplastia de rodilla y cadera. Rev Esp Cir Ortop Traumatol. 2021;65:279–284.