The aim of this study is to analyse the outcomes of the surgical treatment of metacarpophalangeal stiffness by dorsal teno-arthrolysis in our centre, and present a review the literature.

Material and methodsThis is a retrospective study of 21 cases of metacarpophalangeal stiffness treated surgically. Dorsal teno-arthrolysis was carried out on all patients. A rehabilitation programme was started ten days after surgery. An evaluation was performed on the aetiology, variation in pre- and post-operative active mobility, complications, DASH questionnaire, and a subjective satisfaction questionnaire.

ResultsThe mean age of the patients was 36.5 years and the mean follow-up was 6.5 years. Of the 21 cases, the most common cause was a metacarpal fracture (52.4%), followed by complex trauma of the forearm (19%). Improvement in active mobility was 30.5°, despite obtaining an intra-operative mobility 0–90° in 80% of cases. Mean DASH questionnaire score was 36.9 points. The outcome was described as excellent in 10% of our patients, good in 30%, poor in 40%, and bad in the remaining 20%. There was a complex regional pain syndrome in 9.5% of cases, and intrinsic muscle injury in 14.3%.

ConclusionBecause of its difficult management and poor outcomes, surgical treatment of metacarpophalangeal stiffness in extension is highly complex, with dorsal teno-arthrolysis being a reproducible technique according to our results, and the results reported in the literature.

Analizar los resultados obtenidos en el tratamiento quirúrgico de la rigidez metacarpofalángica en extensión mediante tenoartrólisis dorsal en nuestro centro y revisar la literatura al respecto.

Material y métodoEstudio retrospectivo de 21 rigideces metacarpofalángicas intervenidas. En todos los pacientes se realizó tenoartrólisis dorsal de forma ambulatoria, comenzando la rehabilitación a los diez días postoperatorios. Se registró etiología, variación de la movilidad activa tras la cirugía, complicaciones, cuestionario DASH y una encuesta de satisfacción con el resultado.

ResultadosEl seguimiento medio fue de 6,5 años y la edad media de 36,5 años. La causa más frecuente fue la fractura de un metacarpiano (52,4%) seguida de los traumatismos complejos de antebrazo (19%). A final del seguimiento la mejoría en la movilidad activa fue de 30,5° pese a obtener una movilidad intraoperatoria de 0-90° en más del 80% de los casos. En el cuestionario DASH la puntuación media fue de 36,9, calificando el resultado como excelente el 10% de nuestros pacientes, bueno el 30%, regular el 40% y malo el 20% restante. En el 9,5% de los casos se produjo un síndrome de dolor regional complejo y en el 14,3% lesión de la musculatura intrínseca.

ConclusiónPor su difícil abordaje y pobres resultados, el tratamiento quirúrgico de la rigidez metacarpofalángica en extensión es de gran dificultad mostrándose la tenoartrólisis dorsal como una técnica reproducible en relación con nuestros resultados y a los resultados publicados en la literatura.

In 1956 Sterling Bunnell observed that in hand surgery the fingers have a tendency to become rigid, and furthermore that they do so in a non-functional position.1 It is fundamental to understand that the hand is an extremely complex organ in which modification of one of its parts will affect its overall working. This is so to the extent that a single rigid finger may disturb the working of the whole hand and therefore the professional future of the patient.2 Finger mobility requires bone stability, mobile joints, muscular integrity, the sliding of tendons, sensitivity and a suitably elastic skin. This means that practically all lesions of the fingers and hand may lead to rigidity, regardless of whether joints are directly affected by the lesion or not. Additionally, other lesions at different levels of the arm and even systemic pathologies may lead to this restriction in mobility.3

The metacarpophalangeal joint (MCPH) is of the condylar type and permits movements involving flexion-extension and radial and cubital deviation, together with a certain amount of rotational movement, chiefly when it is in extension.2 The main characteristic that differentiates this joint is that its stability varies depending on its position, so that in extension there is less bone contact and the ligaments and capsule are relaxed, so that the joint is less stable. Moreover, when extended intra-joint capacity is maximum, so that an oedema resulting from trauma makes the joint adopt this position.4

Due to its multiple causes, complex anatomy and postoperative results that are often disappointing, suitable treatment of metacarpophalangeal joint stiffness in extension is still a challenge for hand surgeons. Our aim is to analyse the results obtained in the treatment of metacarpophalangeal joint stiffness using dorsal tenoarthrolysis in our hospital, and to revise the results published in the literature.

Material and methodWe present a retrospective study of 21 MCPH stiffness in extension in ten patients operated surgically in our hospital during the period from 2004 to 2011. Their clinical histories were revised and they were evaluated once again.

The inclusion criteria were patients diagnosed with MCPH stiffness in extension (reduction of normal mobility leading to patient functional disability) that had not improved clinically following at least three months of rehabilitation treatment. They also had to be motivated and involved, demanding greater hand mobility for their professional or recreational activities.

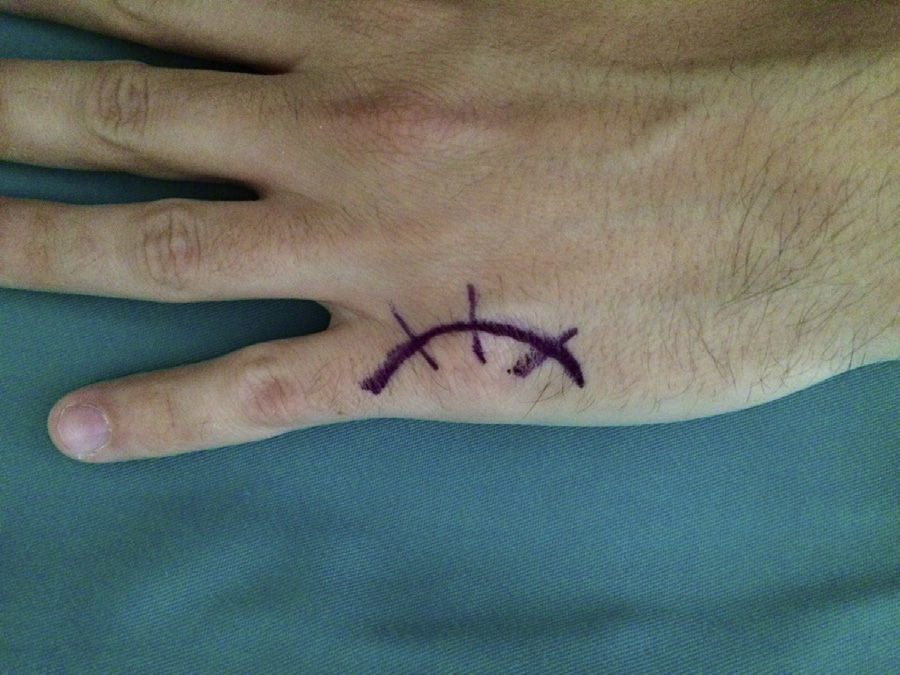

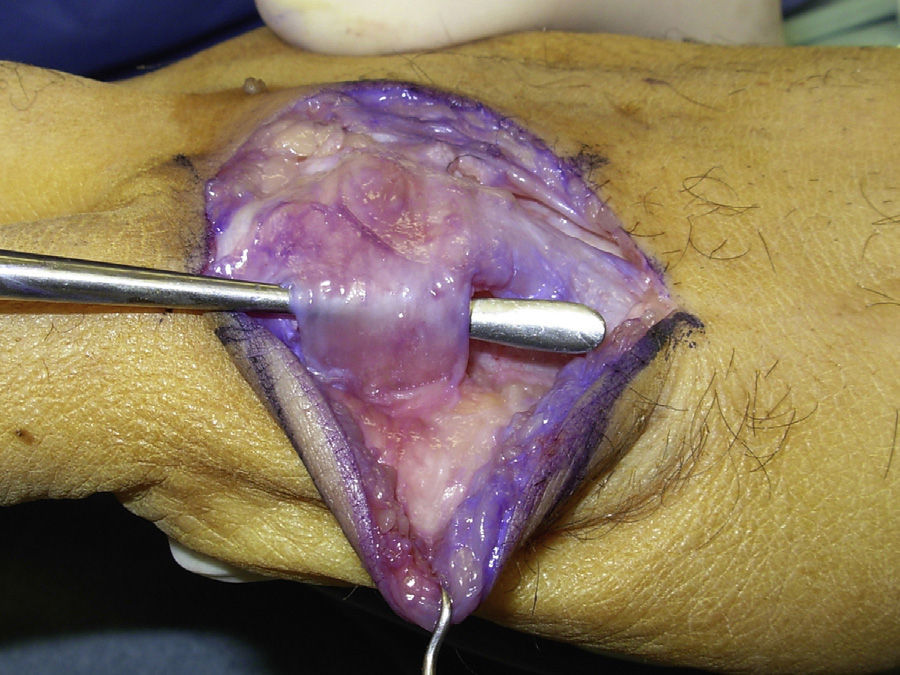

Surgery was carried out on an outpatient basis, under locoregional anaesthesia (the axillary plexus), using a preventive ischaemia tourniquet at the root of the arm and placing the patient's hand on a hand surgery table. When the elasticity of the skin was affected (three cases), we made an arched incision that centred on the MCPH joint (Fig. 1) preserving the dorsal vein return. In those cases where the skin retained its normal elasticity, and when several adjacent fingers were affected, we preferred to make a longitudinal dorsal incision between both affected MCPH joints (Fig. 2). We performed surgery in three successive stages, gently flexing the joint between them. We first carried out tenolysis of the extensor tendon, freeing adherences present in its path. We then performed a dorsal capsulectomy, approaching the joint capsule proximally and the sagittal band distally, respecting the extensor tendon as well as the sagittal band itself, so as not to cause instability of the extensor tendon (Fig. 3). When necessary we also freed the collateral ligaments. And lastly, when complete mobility was not achieved passively (a flexion–extension range of 0–90°), the palmar plate was freed using a blunt spatula through the same dorsal approach.

The skin was closed using absorbable 4/0 suture while keeping the MCPH joint flexed and rotated, and moving the skin flap forwards when necessary (Fig. 4).

A plaster splint was kept in place for the first ten days after the operation, with the MCPH at the maximum flexion achieved. This was then replaced by a passive MCPH flexion orthesis and rehabilitation commenced.

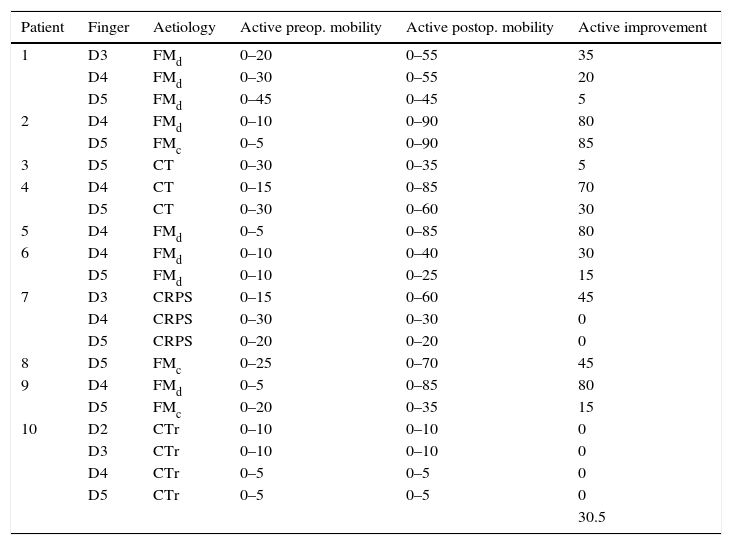

The results were recorded and preoperative active mobility together with postoperative active mobility were evaluated (Table 1), as well as the time taken to return to work, a postoperative upper limb self-reporting DASH questionnaire5 and a satisfaction survey about the result of surgery, in which each patient had to classify the result of the operation as excellent, very good, good, mediocre or poor. The values of the preoperative DASH questionnaire were not available to us.

Pre- and postoperative mobility in the series.

| Patient | Finger | Aetiology | Active preop. mobility | Active postop. mobility | Active improvement |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | D3 | FMd | 0–20 | 0–55 | 35 |

| D4 | FMd | 0–30 | 0–55 | 20 | |

| D5 | FMd | 0–45 | 0–45 | 5 | |

| 2 | D4 | FMd | 0–10 | 0–90 | 80 |

| D5 | FMc | 0–5 | 0–90 | 85 | |

| 3 | D5 | CT | 0–30 | 0–35 | 5 |

| 4 | D4 | CT | 0–15 | 0–85 | 70 |

| D5 | CT | 0–30 | 0–60 | 30 | |

| 5 | D4 | FMd | 0–5 | 0–85 | 80 |

| 6 | D4 | FMd | 0–10 | 0–40 | 30 |

| D5 | FMd | 0–10 | 0–25 | 15 | |

| 7 | D3 | CRPS | 0–15 | 0–60 | 45 |

| D4 | CRPS | 0–30 | 0–30 | 0 | |

| D5 | CRPS | 0–20 | 0–20 | 0 | |

| 8 | D5 | FMc | 0–25 | 0–70 | 45 |

| 9 | D4 | FMd | 0–5 | 0–85 | 80 |

| D5 | FMc | 0–20 | 0–35 | 15 | |

| 10 | D2 | CTr | 0–10 | 0–10 | 0 |

| D3 | CTr | 0–10 | 0–10 | 0 | |

| D4 | CTr | 0–5 | 0–5 | 0 | |

| D5 | CTr | 0–5 | 0–5 | 0 | |

| 30.5 |

FMc: metacarpian neck fracture; FMd: metacarpian diaphysis fracture; CRPS: complex regional pain syndrome; CT: cut tendon; CTr: complex trauma.

70% of the patients were men. Their average age at the time of the operation was 36.5 (24–58) years old, and the average postoperative follow-up lasted for 6.5 (3–10) years.

The fingers were one index finger, three middle fingers, eight ring fingers and nine little fingers.

Stiffness aetiology was metacarpian fracture and subsequent immobilisation of the same in 52.4% of cases (11 cases), of which one was a Gustilo and Anderson grade II open fracture (9%). Three cases (27.2%) had been operated on, two by percutaneous surgery and one by open reduction and osteosynthesis. In four cases (19%) the rigidity was due to complex forearm trauma with a grade IIIA open fracture. In three cases (14.3%) the aetiology was parting of the extensor tendon followed by surgical treatment and immobilisation. In the remaining three cases (14.3%) the cause was a type I complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS) following entrapment of the hand under the patient's body.

Intraoperatoratively a passive mobility of at least 0–90° was achieved in 17 of the 21 cases (81%). Nevertheless, at the end of follow-up the average improvement in the mobility of our patients was 30.5°, with a standard deviation of 34 and an IC of 95% (14.8–46.1). This improvement stabilised after four months of postoperative treatment (Table 1).

When the patients are divided into subgroups according to their aetiology, we found that when rigidity is caused by a fracture, the average improvement in mobility was 44.5° (5°–85°). When the cause was complex trauma of the arm, active postoperative mobility did not improve. When the aetiology was parting of the extensor tendon, active postoperative mobility improved by an average of 35° (5°–70°) while lastly, when the cause was CRPS, active postoperative mobility increased by an average of 15° (0°–45°).

On the other hand, if the patients are divided according to the finger affected, when it was the index finger no improvement was achieved; in the middle fingers (three cases) active mobility increased by an average of 26.7° (0°–45°); in the case of the ring finger (eight cases) it improved by an average of 45° (0°–80°); and for the little finger (nine cases) active mobility increased by an average of 22.3° (0°–85°).

Lastly, when the results are analysed according to the number of fingers affected, when one or two fingers were affected by rigidity (eight patients), the average improvement in active mobility was 42.5°, while when three or four fingers were affected (two patients), it only improved by 6.4°.

In terms of their return to work, 60% of our patients were able to return to the same job they performed prior to their injury. 30% of the patients returned to work but had to do a different job from the one they had before their injury. These patients (90%) started work again after an average time of 3.8 (3–4) months following surgery. The remaining 10% of our patients did not return to work.

In the DASH questionnaire, the patients in this series obtained an average score of 36.9 (4.5–70.4) points. When they were asked about their level of satisfaction with the result of the operation, 10% described it as excellent, 30% of the patients considered it to be good, 40% stated that it was mediocre and the remaining 20% described it as poor.

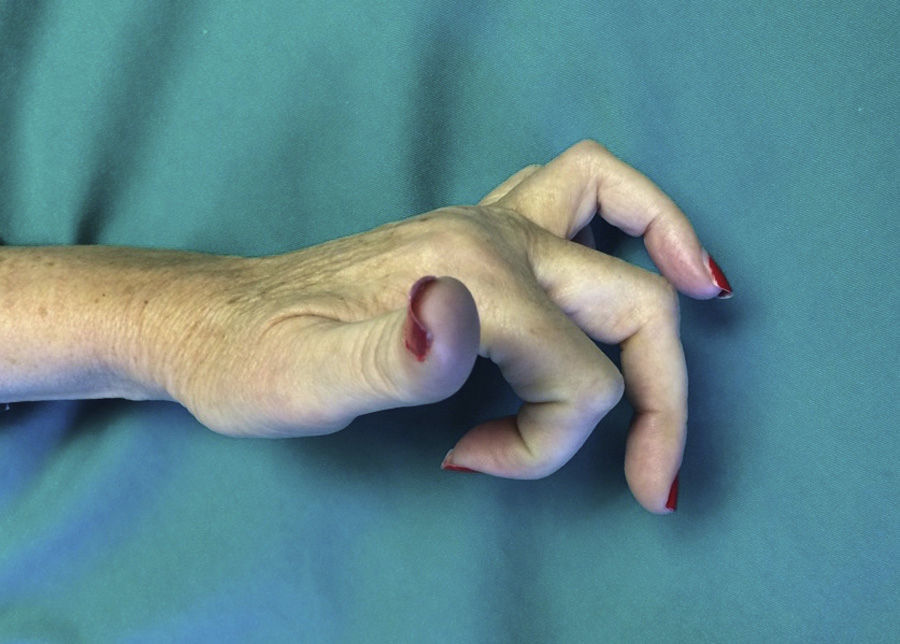

In terms of complications, two cases (9.5%) developed type I CRPS after the operation, and three (14.3%) a situation of “extrinsic finger” arose, characterised by hyperextension of the MCPH joint that could not be actively reduced (Fig. 5). We believe that this was due to excessively aggressive liberation, with injury to the intrinsic musculature. These patients refused further surgical treatment.

DiscussionThe aim of treatment in cases of stiffness is to achieve a stable, mobile and painless joint. The ideal treatment is prevention following any trauma or surgery, preventing pain and the oedema and placing the hand in a suitable position, on condition that this is possible following the procedure used. That is, with the wrist in 10° extension and the MCPH joints flexed at 90° with the interphalangeal joints in extension.4,6 Up to 66% of cases have been estimated to be iatrogenic, and they are therefore potentially avoidable.7 Moreover, this lesion often affects young patients and therefore has a major impact on their working life.

Once stiffness has been established, conservative treatment using different types of orthesis is effective, achieving resolution of the clinical symptoms in 63.9–87% of cases, according to different authors.4,8,9 There are four types of orthesis: continuous static, discontinuous static, progressive static and dynamic splints, all of which have been proven to be effective,2,4 although the exact pressure that they should apply has not been determined,3 or how long the patient should wear them every day, as has been determined for proximal interphalangeal joint flexion stiffness.10

Surgical treatment should only be considered when conservative treatment is not effective. There is currently no available evidence that would make it possible to know when surgery is indicated. However, some authors recommend it when correctly applied conservative treatment has attained a plateau without further improvement and the mobility arch is unacceptable2 after at least three months.3,4

Surgical treatment should be indicated when joint surfaces are intact, although this is not indispensible.2,4 It is also indicated when joint motors work properly4 and, most importantly, when the patient is aware of his lesion and is motivated, given that surgery is only the first step in a long and difficult process of recovery that he must understand and accept. Additionally, it is not rare for rigidity to reappear in spite of having a cooperative patient, suitable surgery and a correct rehabilitation team.2,4

There are not many works in the literature on the results of surgical treatment for MCPH extension rigidity. The published series do not contain a large number of cases, and moreover most of them are from the last century, so that they are less relevant in terms of improvements in the prevention and physiotherapeutic treatment of stiffness.

Weeks et al.8 showed that a volar approach is superior to a dorsal one in terms of joint movement improvement. In spite of this, the majority of authors and we ourselves prefer a dorsal approach, as it is direct and permits suitable exposure dorsal structures and the MCPH joint itself.2–4,11,12

Buch et al.11 published their results of operating on 27 hands, achieving an active mobility of at least 30° flexion. They emphasise the importance of early mobility after surgery. Young et al.12 published their results using dorsal tenoarthrolysis with a Kirschner needle to keep the MCPH flexed for two weeks after surgery; with this technique they achieved a passive MCPH mobility of 48°. Gould and Nicholson13 published the largest series in the literature, with 105 dorsal MCPH capsulotomies in which they achieved an intraoperative mobility of 0°–90° and an average increase in mobility at the end of the follow-up period of 21°. This falls to 18° when the cause is a fracture or crush injury, in spite of which the authors conclude that the surgery is worthwhile.

Wiznicki et al.14 publish a work describing their treatment of 65 cases of MCPH and interphalangeal rigidity with a 28° improvement in mobility.

In the 1990s Mansat et al.15 published the series showing the greatest increase in active mobility, with an average of 40°, while Foucher16 published a 38° improvement in mobility.

The average improvement in active mobility in our series was 30.5°, which is similar to the improvement shown in the literature consulted. The results were far superior in the cases with rigidity of one or two fingers than they were when three or four fingers were affected (a 42.5° improvement vs. 6.4°) while the mobility of the fourth finger improved the most.

We use a proximal approach to the MCPH joint and a distal approach to the sagittal bands to prevent cutting the tendon or the bands themselves, thereby avoiding the need for suture of the extensor apparatus, which should be protected by keeping the hand immobilised. Based on findings in the literature, this would be a theoretical advantage, and we do not know whether it would really affect the final result, given that our results are similar to those published by other authors who part the sagittal band11,13 or divide the extensor tendon longitudinally.2,12

In the series of Gould and Nicholson,13 like ours, the discord between the passive mobility obtained intraoperatively and the active mobility at the end of follow-up stands out. The cause may be the delay in starting rehabilitation treatment and pain following aggressive surgery which hinders postoperative mobilisation. We believe coordination with the rehabilitation services to be fundamental to start therapy early, as well as coordination with the Anaesthesiology/Pain Unit to control postoperative pain, with catheters to aid mobilisation.

On the other hand, the Wide Awake Local Anaesthesia No Tourniquet technique is of interest. This was recently described by Lalonde,17 and it makes it possible to evaluate active mobility during the operation, guiding the different surgical actions and directly instructing the patient.

To conclude, it seems clear that the ideal treatment is to prevent stiffness and, once it has commenced, to make full use of conservative treatment. When surgery is necessary, it is fundamental to correctly select a motivated patient who has received good advice, as they will have to understand that the recovery process will be long and arduous, and that surgery is only the first step. We believe that dorsal tenoarthrolysis is a reproducible technique in terms of the published results in the literature and those obtained by us. The final situation stabilises about four months after the operation and the results that may be expected are generally not very satisfactory.

We therefore believe that surgical treatment for metacarpophalangeal stiffness in extension is still a challenge for hand surgeons.

Level of evidenceLevel of evidence IV.

Ethical responsibilitiesProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this investigation.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work centre on the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appears in this article.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Please cite this article as: Jiménez I, Muratore-Moreno G, Marcos-García A, Medina J. Rigideces metacarpofalángicas en extensión. ¿Un desafío para el cirujano de mano?. Rev Esp Cir Ortop Traumatol. 2016;60:215–220.