Plantar fasciitis (PF) is one of the most frequent causes of thalalgia and disability. The effectiveness of extracorporeal shock wave therapy is an ideal alternative to conservative treatments.

ObjectiveTo evaluate the effectiveness of the treatment with Piezoelectric Focal Shock Waves with echographic support and maintenance of the effect at 3 and 6 months.

Materials and methodsCausi-experimental, retrospective statistical study, June 2015 to June 2017, of 90 patients, 36.6% men and 63.3% women, with a mean age of 52 years, diagnosed with PF. Three sessions (one weekly for 3 weeks) of shock wave therapy (PiezoWave F10 G4 generator) were performed, with echographic support and weekly revision and at 3 and 6 months. Main variables: pain, using Visual Analogue Scale before and after each session and at 3 and 6 months and Roles and Maudsley Scale at the end of treatment and at 3 and 6 months.

Results2000 pulses per session were applied, medium energy intensity .45mJ/mm2, median frequency 8MHz and median depth of focus of 15mm. Statistically significant improvement was observed in the Visual Analogue Scale between the 3 treatment sessions and after 3 and 6 months post-treatment, obtaining a statistically significant improvement in all values (p<.05).

ConclusionTreatment with piezoelectric focal shock waves in PF may reduce pain from the first session and achieves a subjective perception of improvement, maintaining these results at 6 months post-treatment.

La Fascitis plantar (FP) es una causa frecuente de talalgia y discapacidad. Pretendemos valorar la efectividad del Tratamiento con Ondas de Choque (TOC) Focales Piezoeléctricas con apoyo ecográfico y mantenimiento del efecto a 3 y 6 meses.

Material y métodosEstudio retrospectivo cuasi-experimental junio 2015 a Junio 2017, con 90 pacientes, 36,6% hombres y 63,3% mujeres, edad media 52 años, diagnosticados de FP. Se realizaron 3 sesiones (una semanal durante 3 semanas) de tratamiento con Ondas de Choque (Generador PiezoWave F10 G4), con apoyo ecográfico, con revisión semanal, a los 3 y 6 meses. Variables principales: dolor, cuantificado mediante Escala Visual Analógica (EVA) antes y después de cada sesión, a los 3 y 6 mesesy Escala de Roles y Maudsley al final del tratamiento y a los 3 y 6 meses. Se aplicaron 2000 pulsos por sesión, energía media 0,45 mJ/mm2, mediana de frecuencia 8 MHz y mediana de profundidad del foco 15 mm.

ResultadosSe obtuvo mejoría estadísticamente significativa mediante EVA entre las 3 sesiones de tratamiento y al cabo de 3 y 6 meses post-tratamiento, obteniendo una mejoría estadísticamente significativa en todos los valores (p<0.05). Según la escala Roles y Maudsley, el 69,7% de los pacientes consideran el resultado bueno o excelente a los 3 meses y un 68,9% a los 6 meses; resultado estadísticamente significativo.

ConclusiónEl TOC piezoeléctricas focales con apoyo ecográfico puede constituir una buena opción terapéutica en FP. Reduce el dolor desde la primera sesión, y consigue una percepción subjetiva de la mejoría mantenida a los 6 meses post-tratamiento.

Plantar fasciitis (PF) is one of the most common causes of foot pain in adults. It presents clinically as pain in the internal process of the calcaneal tuberosity, the proximal insertion point of the plantar fascia.1 Its highest incidence is in the population aged between 40 and 60, and in a third of cases it is even bilateral. It presents in sedentary people and marathon runners alike, and therefore 10% of the population will suffer the condition at some time in their lives.2,3 Although its aetiology is not completely clear, it is likely that not a single but various factors contribute to its onset, most notably, being female, overweight, frequent standing as well as sedentariness, and anatomical conditions such as the architecture of the foot (pes cavus, forefoot valgus, with low hallux mobility), contracture of the posterior muscle chain of the lower limb and atrophied plantar fat.4,5

PF is a musculoskeletal disorder with clinical symptoms of pain that is more intense when starting to walk in the mornings or after a period of rest, and increases with prolonged standing or with high-impact activities.6

Diagnosis is made by clinical history and physical examination, and confirmed by ultrasound, which rules out micro-tears, and determines the thickness of the fascia. The diagnostic criterion is a thickness >4mm. Ultrasound and MRI are the first and second-line modalities respectively for diagnosing PF.7

Treatment of PF includes a change of lifestyle. Oral analgesics and NSAIDs, fascial stretching exercises, massages and local cold compressions constitute the first-line treatment. If there is no improvement with this first approach, rehabilitation should be considered: physiotherapy (eccentric stretching, myofascial massage, electrotherapy), plantar orthoses or local corticosteroid injections, PRP,8,9 or botulinum toxin.10,11

Extracorporeal shock wave therapy (SWT) is a treatment proposal that has recently been demonstrated as safe and effective. It is useful for patients with chronic plantar fasciitis (CPF) refractory to the abovementioned treatments.12–14 With the increasingly widespread use of ultrasound, locating the transducer application point in SWT is becoming more accurate.

This study presents the results recorded after one year of using piezoelectric focal waves to treat PF, with ultrasound support, in patients in our rehabilitation department.

Material and methodsWith the favourable report of our hospital's clinical research ethics committee (Favourable Report of the Biomedical Research Project, C.P.-C.I. 17/327-E), we performed an analytical quasi-experimental study, for which we selected a non-randomised sample of 90 patients from June 2015 to July 2017.

All the patients, before they were treated with shock wave therapy, were duly informed of the objectives of the treatment, and its possible complications and advantages over other therapeutic options. All of the patients signed their informed consent.

Inclusion criteriaPatients from our own department were included in this study as well as those referred from the rheumatology and traumatology departments, over the age of 18, with CPF (with a history of more than 6 months), who had undergone a previous treatment (plantar orthesis, physiotherapy, corticosteroid injection), with a level of over 4 on the visual analogue scale (VAS). They all underwent a diagnostic ultrasound beforehand to confirm the condition, and to minimise any complications.

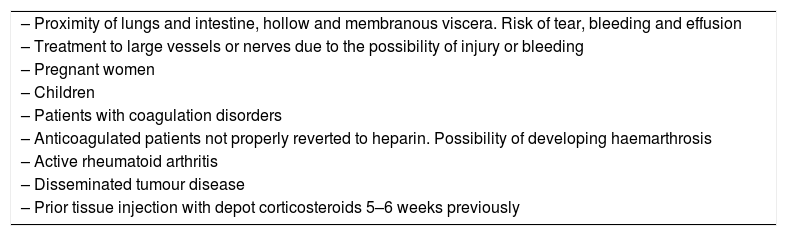

Exclusion criteriaPatients for whom the treatment was contradicted in any way according to the Spanish Society for Shockwave Treatments15 (Table 1) were excluded from the study. Patients who had received corticosteroid injections within the preceding 6 weeks were not offered treatment (they were able to receive the treatment after that period of time had elapsed), and neither were those with a VAS value of under 4, or those who voluntarily rejected the treatment.

Contraindications for the treatment.

| – Proximity of lungs and intestine, hollow and membranous viscera. Risk of tear, bleeding and effusion |

| – Treatment to large vessels or nerves due to the possibility of injury or bleeding |

| – Pregnant women |

| – Children |

| – Patients with coagulation disorders |

| – Anticoagulated patients not properly reverted to heparin. Possibility of developing haemarthrosis |

| – Active rheumatoid arthritis |

| – Disseminated tumour disease |

| – Prior tissue injection with depot corticosteroids 5–6 weeks previously |

Source: Taken from the Spanish Society of Shock Wave Treatments (Sociedad Española de Tratamientos con Ondas de Choque) (SETOC).

The variables studied were: age, sex, length of time with pain in the fascia, presence or otherwise of calcaneal spur, fascial thickness in both feet, having had physiotherapy, having received corticosteroid injections, using custom-made plantar ortheses or heel pads, regularly practising high-impact sports or high-impact work, presence of limited joint balance in the ankle (dorsi and plantar flexion tests), body mass index greater or less than 30, and being actively employed or otherwise.

Treatment-dependent variables: pain was assessed by VAS score and patient satisfaction using the Roles and Maudsley scale that classifies the treatment result according to the patient's evaluation as excellent, good, fair or poor. We assessed the maximum pain in the fascia on weight bearing during the day and at rest before starting shockwave treatment, pain in the last week at the start of each session, and the VAS score on placing weight on the foot immediately after applying the treatment. All the patients were advised to follow a programme of specific stretches to do at home. After the final session the patients were asked to rate the result obtained post-treatment, using the Roles and Maudsley satisfaction scale. These patients were reviewed at 3 and 6 months and asked about their maximum pain on weight bearing during the day and at rest (VAS), and their subjective result obtained using the Roles and Maudsley satisfaction scale. All the checks were undertaken in the clinic, except for the 6-month evaluation, when the information was collected over the telephone.

InterventionExtracorporeal SWT was applied using a piezoelectric generator (PiezoWave F10G4, Richard Wolf, Knittlingen, Germany), with the patient in a prone position. Ultrasound (6–12 linear probe) enabled us to see the injury and evaluate the presence of enthesitis in the inferior pole of the calcaneus, measure the fascial thickness and locate the depth of focus for application. The mean depth of focus was 15mm, the mean energy density used was .45mJ/mm2 (applied as tolerated by the patient,) and the frequency was 8Hz in all cases. Two thousand pulses were applied in each session; 3 sessions were delivered in total, one per week, with a review at 3 and 6 months.

During the weeks of treatment, the patients were advised to do analytical bilateral stretching exercises of the triceps surae (gastrocnemius and soleus) and plantar fascia. Patients who were observed to have a pes cavus, forefoot valgus or faulty biomechanics that might aggravate or perpetuate their symptoms were prescribed plantar orthoses 3 months after finishing the treatment.

The doctors who performed the SWT were all trained in plantar fascia ultrasound. They formed a total of 3 teams each with 2 doctors, after they had agreed the anatomical references of ultrasound measurement.

Statistical analysisThe data were analysed using SPSS for Windows, version 23. The chi-squared test was used to compare the 2 qualitative variables, and the Wilcoxon test to compare the qualitative variables that did not follow a normal distribution. Mean and standard deviation were used to describe the quantitative variables that followed a normal distribution, and the median and interquartile range for those that did not. In the case of a qualitative variable with more than 2 categories, the ANOVA or Kruskal–Wallis tests were used respectively. The result was considered statistically significant if the level of significance was p<.05.

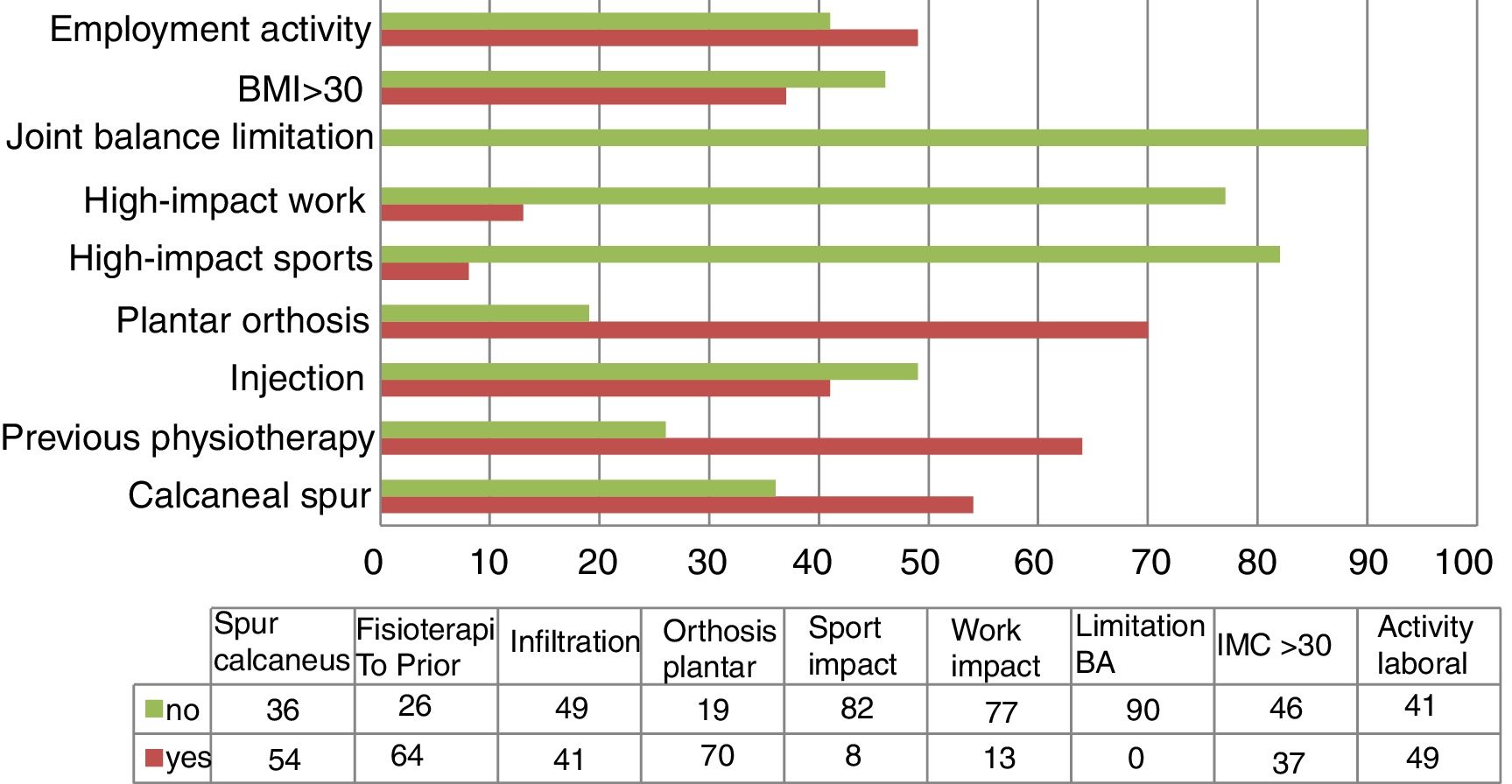

ResultsNinety patients were treated, 57 women and 33 men, with a mean age of 52 years. The mean length of time with the condition was 16 months. Fig. 1 specifies the characteristics of our sample with regard to the risk factors for developing PF and lifestyle habits. The principle variable is improvement of pain according to VAS score, and the following variables were analysed secondarily: presence or otherwise of calcaneal spur, having undergone physiotherapy beforehand, having undergone corticosteroid injection in the 3 previous months, prior use of custom-made plantar ortheses or heel pads, routinely practising high-impact sports or high-impact work, limited joint balance in the ankle (dorsi and plantar flexion tests), body mass index greater or less than 30, and in active employment or otherwise. No statistically significant relationship was found for any of these variables with greater or less reduction in pain intensity (VAS) (p>.05). Neither was a relationship found in an increase or reduction of pain (VAS) with the intensity of the energy used during the technique (p>.05). The effect was not analysed of the plantar ortheses prescription (3 months after the treatment) on the results obtained on the VAS at 6 months, but how it might have influenced a greater or lesser reduction of the VAS score before the review at 3 months following the treatment was analysed; this relationship was not statistically significant (p>.05).

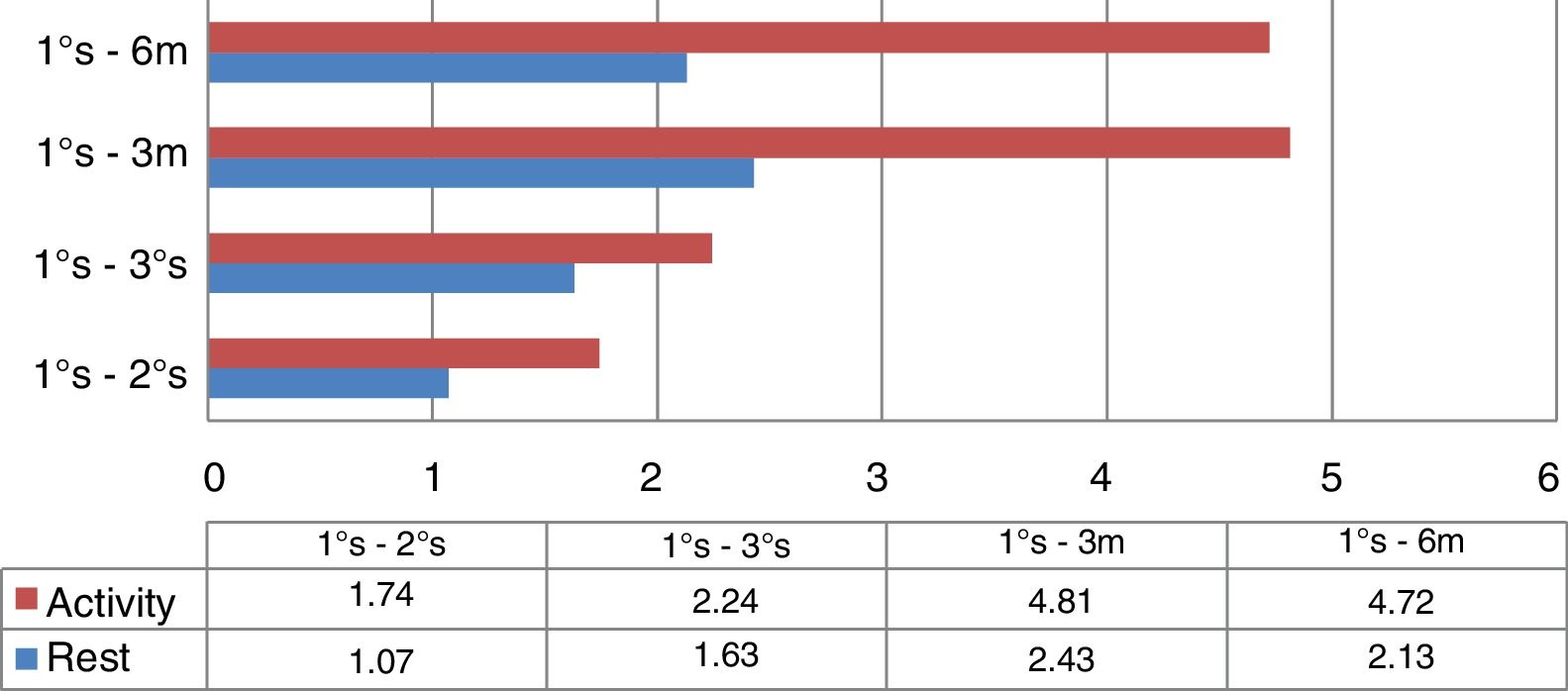

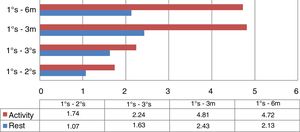

With regard to the VAS score results, the patients of our sample started with a mean value of 3.5 (95%CI: 3.93–3.07) at rest, and 8.6 (95%CI: 8.86–8.34) as the maximum pain on weight bearing during the day. The means at 6 months following the treatment were 1.6 (95%CI: 2.09–1.11) at rest, and 3.1 (95%CI: 3.65–2.55) as the maximum pain on weight bearing during the day, respectively. On comparing the VAS values at rest and the maximum pain on weight bearing during the day between the 3 treatment sessions, and after 3 and 6 months following the SWT, a statistically significant improvement was see in all the scores (p<.05) (Fig. 2).

Differences in mean VAS score (during activity and at rest) between the first session, successive sessions, and the follow-up at 3 and 6 months. From the bottom upwards it can be appreciated how the difference between the mean VAS scores increase, with a slight reduction at the 6-month follow-up.

According to the Roles and Maudsley scale, at 3 months, 36% of the patients reported that the treatment result was excellent; 33.7%, that it was good; 19.1% rated it as fair, and 11.2% of the sample considered it poor. The figures were similar at 6 months: 37.7% with an excellent result; 31.2%, good; 19.5%, fair, and 11.7%, poor. Eleven of the patients were lost to follow-up at the 6-month follow-up.

With this treatment, no adverse effects or complications were recorded using the technique in any of the cases.

DiscussionIn this analytical paper we present our experience with SWT with a piezoelectric generator: there are very few studies that have used this type of generator.

Numerous studies have examined the different treatment alternatives for PF.16–20 This is a very common condition with multiple risk factors, and therefore, in many cases, these therapeutic options are not effective.

PF is a self-limiting musculoskeletal disorder, since in 80%–90% of cases the symptoms will disappear within 10 months. However this time interval is frustrating for both the patients who suffer the condition, and for the specialist treating them. Therefore, the sooner the condition is diagnosed and treatment started, the better the likelihood of a cure.

In their systematic review on the effectiveness of the different conservative treatments (orthopaedic, physiotherapy – bandages, stretches-, electrotherapy-ultrasound, shock waves, iontophoresis, laser and magnetotherapy- and acupuncture), Díaz López and Guzmán Carrasco21 studied 32 articles, in which stretching and shock waves were the techniques used most frequently, although the best results were obtained by combining various techniques. Shock waves were effective when other techniques had failed.

The gold standard treatment for PF is conservative. The physical therapies used in our different studies were demonstrated as effective, to varying extents, in reducing pain or alleviating the symptoms of PF. Surgery is not usually resorted to as first-line treatment because it does not always give good results, and there is recurrence in 30% of cases.

Focal SWT has been proposed as an option for the treatment of PF, in addition to other musculoskeletal conditions. Wang et al., in a review published in 2012,22 conclude with regard to extracorporeal SWT for PF that, since there are so many confusing factors that influence the effects of the results of this therapy, the results obtained could be controversial. However the large majority of the studies reviewed are in favour of extracorporeal SWT, with a success rate ranging from 34% to 88%.

There is no consensus regarding the density of energy applied or the treatment parameters. In a meta-analysis, Dizon et al.23 reviewed various studies and analysed the results in terms of pain and function according to the intensity of the energy applied, and observed, in addition, the adverse events recorded in each. They concluded that shock waves at moderate and high frequency are effective in reducing pain and in improving function for CPF and, although the treatment could cause pain, it was well tolerated by the patients and of short duration. In terms of protocol, Rompe et al.24 propose 3 weekly sessions of 1000 pulses at low energy as effective therapy. However, in one of their papers Wang et al.25 gave one single treatment and reported good results up to 72 months afterwards.

There are 3 ways of generating the focal shock wave, with an electrohydraulic, electromagnetic or piezoelectric generator. The latter has high intensity focus, but this focus is the smallest of the 3, therefore the total energy is less. It has the advantage of being less painful and better tolerated by the patient.

In the study by Liang26 (piezoelectric device), 2 patient groups with PF were randomly treated: one received shock waves at high intensity (.56mJ/mm2) and the other at low intensity (.12mJ/mm2). They obtained similar results in improved pain and function with both high and low intensity, and although less pain was associated with high intensity, it did not provide more favourable success rates, which went from 67% at 3 months to 58% at the 6-month follow-up.

In our study, when the differences in the mean VAS scores between the first treatment session and the subsequent sessions were analysed, and with the post-treatment follow-ups at 3 and at 6 months, we can observe how the difference between the mean VAS scores increases, with a slight decrease at 6 months.

Comparing the mean VAS scores (maximum pain on weight-bearing during the day and at rest) reported by the patients between the first and the successive sessions (second-third), and later with the post-treatment scores at 3 and at 6 months, an increase in the differences of these values can be appreciated over time, which translates into improved pain for the patient, maintained medium and long term, according to the results of our study. The loss to follow up of 11 patients might have influenced this slight reduction at 6 months.

In their meta-analysis, Sun et al.27 compare the efficacy of extracorporeal shock waves in general, focal shock waves and radial shock waves with a placebo to assess their effectiveness for chronic PF. They conclude that focal shock wave therapy can alleviate pain in chronic PF as an ideal alternative option; whereas they cannot reach firm conclusions on the general effectiveness of shock waves or radial shock waves. Due to the variations in the studies included in this meta-analysis, additional trials are required to validate these conclusions.

There are few studies that analyse the efficacy of shock waves for PF with a piezoelectric-type device, therefore it would be interesting to establish which shock wave generator might be most effective, and whether less total energy density in the focus, as with the piezoelectric generator, influences the efficacy of this treatment.

The main limitations of this study are that we could not quantify whether or not the patients made changes to their lifestyle habits, which could mean that the favourable results obtained were influenced by these changes, by the natural evolution of the condition or by the use of custom-made plantar orthoses, and not due the use of extracorporeal SWT alone. It would be interesting to undertake a comparative study of the efficacy and tolerance of this treatment compared to plantar fascia injections or with a control group, which this study lacked. To that end, future studies are necessary to clarify the most effective solutions for treating PF.

Another limitation of this paper is that we did not study the number of patients who might have had morphological alterations of the foot, and what these were. We only recorded whether or not they wore an insole before the treatment, and therefore we did not study whether this factor might be linked to the results obtained on the VAS scale. This could also be another future line of research.

ConclusionsAccording to the results obtained in our study, focal piezoelectric SWT applied at high energy intensity reduces the pain of PF from the first session, improving and maintaining this result even at 6 months following the treatment, an improvement which is statistically significant. Similarly, the great majority of the patients treated considered that they had achieved a positive result with this therapy (Roles and Maudsley scale), and were satisfied.

Focal piezoelectric SWT is an effective therapeutic alternative for the resolution of PF for patients with the condition. It is safe because there are no recorded complications and very well tolerated compared to other interventionist techniques. Professionals working in the field of musculoskeletal entities should be aware of and consider using the treatment.

Level of evidenceLevel of evidence I.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Vaamonde-Lorenzo L, Cuenca-González C, Monleón-Llorente L, Chiesa-Estomba R, Labrada-Rodríguez YH, Castro-Portal A, et al. Aplicación de ondas de choque focales piezoeléctricas en el tratamiento de la fascitis plantar. Rev Esp Cir Ortop Traumatol. 2019;63:227–232.