Inappropriate prescribing (IP) is an important cause of health problems among elderly and complex chronic patients (CCPs).

ObjectiveSurveillance of IP prevalence among elderly and CCPs in a health department. IP time trends across the period 2015–2019.

MethodDescriptive population-based study. Setting: ‘València-Clínic-Malvarrosa’ Health Department, Valencia, Spain. Period: 2015–2019. Subjects: Complete set of CCPs in the department, defined by clinical risk groups. Number of CCPs (annual average in the period): 9102 (75% ≥65 years of age). IP was measured using an indicator consisting of 13 specific types of prescriptions defined as inappropriate. Analyses: frequencies and time trends, both overall and by specific type.

ResultsOverall prevalence of IP ranged from 0.276 (2015) to 0.289 (2018) per patient, without time trend. The most frequent inappropriate prescription was type 1: “≥75 years of age with inappropriate medication”, which showed a stable rate across the period. Some types of inappropriate prescriptions displayed favourable decreasing time trends, while others showed no change or an unfavourable trend (i.e., joint prescription of absorbents and urinary antispasmodics).

ConclusionsIP prevalence is a serious and persistent problem among the elderly and CCPs, especially in the oldest. It is therefore necessary its continuous surveillance (overall and by specific types of prescription). As well as interventions to optimise prescribing, thus improving the quality and efficiency of care for the elderly and CCPs.

La prescripción inapropiada (PI) es una importante causa de problemas de salud en las personas mayores y pacientes crónicos complejos (PCC). Objetivo: Monitorizar la prevalencia de PI en personas mayores y PCC, en un departamento de salud. Tendencias temporales de la PI durante 2015-2019.

MétodoEstudio descriptivo de base poblacional. Lugar: Departamento de Salud «València-Clínic-Malvarrosa», Valencia, España. Periodo: 2015-2019. Sujetos: Conjunto completo de PCC en el Departamento, definidos mediante Clinical Risk Groups. Número de PCC (valor promedio anual en el periodo): 9.102 (75% ≥65 años de edad). La PI se cuantificó mediante un indicador que comprende 13 tipos concretos de prescripciones definidas como inapropiadas. Análisis: frecuencias y tendencia temporal, global y por tipos.

ResultadosLa prevalencia global de PI osciló entre 0,276 (2015) y 0,289 (2018) por paciente, sin tendencia temporal. El tipo concreto de PI más frecuente fue el 1: «≥75 años con medicación inapropiada», y fue estable en el periodo. Algunos de los tipos inapropiados de prescripción mostraron evolución temporal favorable, descendente; pero en otros no hubo cambios o fue desfavorable (como la prescripción conjunta de absorbentes y antiespasmódicos urinarios).

ConclusionesLa prevalencia de la PI constituye un problema importante y persistente en las personas mayores y PCC, especialmente en las de más edad. Es pues necesaria su monitorización continuada (global y por tipos de prescripción), así como intervenciones para optimizar la prescripción, mejorando la calidad y eficiencia de la asistencia a las personas mayores y PCC.

Inappropriate prescribing (IP) of medications is an important health problem. According to Delgado Silveira E. et al.,1 its prevalence in Spain is as follows: using STOPP criteria (Screening Tool of Older Person's potentially inappropriate Prescriptions), it is 21–51% in the community, 48–79% in nursing homes, 25–58% in acute care hospitals, and 53% in medium-stay hospitals; and using START criteria (Screening Tool to Alert doctors to the Right Treatment), it is 20–54% in the community, 29–74% in nursing homes, 31–57% in acute care hospitals, and 46% in medium-stay hospitals.1 IP causes drug-related problems, adverse drug reactions, and increased morbidity, mortality and health costs.

Some groups are especially susceptible to IP, such as persons of advanced age and complex chronic patients (CCPs) in general. These patients are more vulnerable to IP for several reasons, including polypharmacy; age-related changes, both physiological and in drug metabolism; comorbidity and pluripathology, requiring care at various healthcare levels and by multiple medical specialisations; and the characteristics of prescriber-patient interaction.2

IP may be due to the use of drugs that cause harm, the omission of necessary drugs or incorrect directions. Different strategies have been proposed to optimise drug use, ranging from Beers and STOPP–START criteria to the Improved Prescribing in the Elderly Tool (IPET) and Medication Appropriateness Index (MAI).3,4 Furthermore, to reduce the effects of IP, several deprescribing procedures have been established,5 such as reconciliation, review, deprescription and improved therapeutic adherence, with the clinical review being the most complete.6

Given the relevance of identification of prescribing problems in the National Health System, coupled with the need to measure and follow-up such problems in the population of advanced age and CCPs, it is important to have a standardised, systematically applied system for their detection and quantification. A recent indicator proposed to quantify the prevalence of IP is the so-called “prescription incidents rate”, in which incidents, i.e., inappropriate prescriptions, are “cases of non-compliance with guidelines on safety and rational use of medications identified in patients’ prescriptions”.7

The purpose of this paper is to report the prevalence of IP among elderly and CCPs, and its time trend across the period 2015–2019 in a health department of Valencia, Spain.

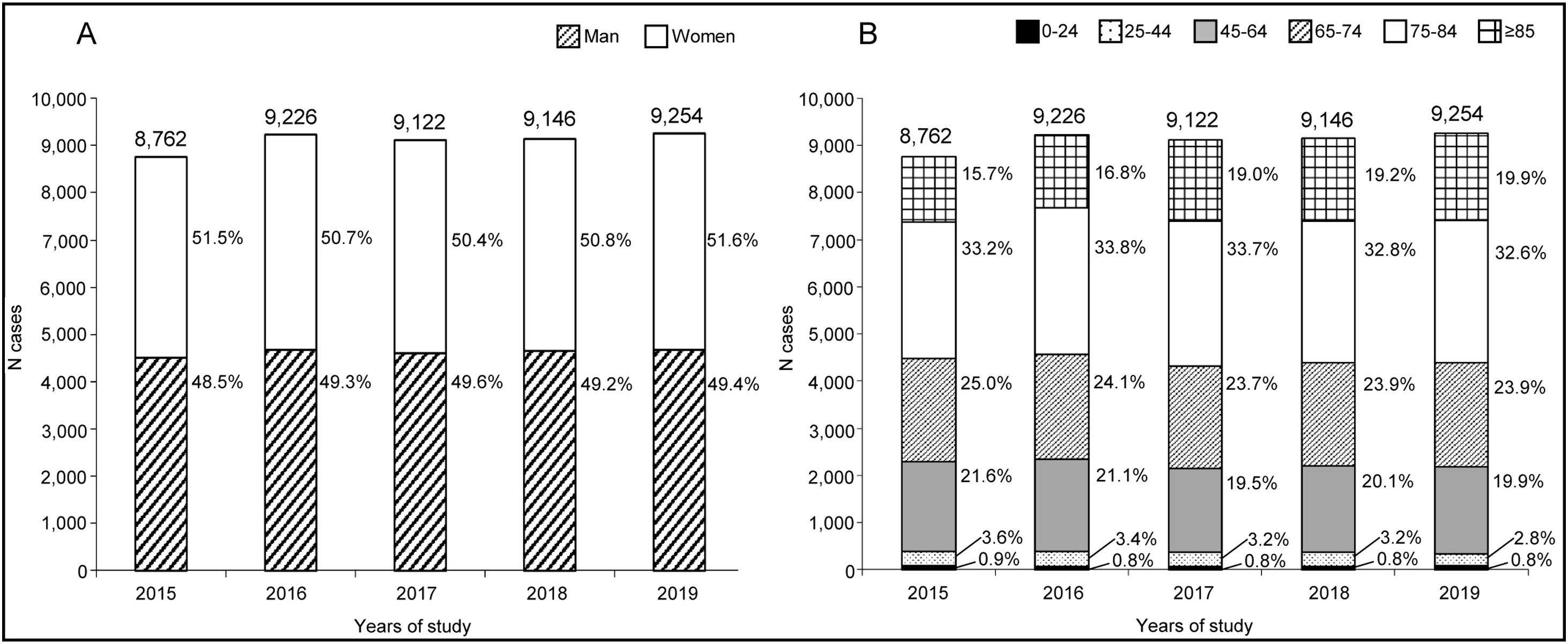

Material and methodsWe conducted a descriptive population-based study, using aggregate data, confined to the ‘València-Clínic-Malvarrosa’ Health Department, in Valencia, Spain, across the period 2015–2019. The study population was the complete set of CCPs in the department, defined by reference to clinical risk groups (CRGs).8 This is a patient-classification system based on diagnostic data and clinical risk, implemented and automated for the entire Valencian Region (Comunidad Valenciana). Subjects matching the following CRGs were included as CCPs: health status 5 (severity level 6); health status 6 (severity levels 5 and 6); health status 7 (severity levels 1–6); health status 8 (severity levels 1–5); and health status 9 (severity levels 1–6).9,10 These levels correspond to patients with one, two or three dominant chronic diseases and advanced severity levels, advanced neoplasms, or high healthcare needs. Study subjects were required to be on medication, be registered in the Population Information System, and have a primary care physician assigned to them.11 We excluded subjects who were not recipients of direct healthcare from the Valencian Health Authority (e.g., civil servants, and members of the judiciary and armed forces covered by mutual insurance societies) and all those who did not belong to the above CRGs. The annual study population, with an annual average of 9102, ranged from 8762 to 9254 patients. Overall, 75% of subjects were ≥65 years of age (Fig. 1).

The indicator used in this study to measure IP prevalence was based on the above mentioned prescription incidents rate7; and was made up of a list of 13 quantifiable specific types of prescriptions defined as inappropriate (IP-types) (see short definitions in Table 1). This list was taken from the one developed by the Catalonian Regional Authority's Chronic Care and Prevention Programme (Programa de Prevenció i Atenció a la Cronicitat) to calculate the mentioned rate and was based on several criteria, including Beers, PRISCUS, McLeod, and STOPP–START.6 Specifically for IP-type 1, the IP criterion was that the medication should be included in the Beers 2015 and/or STOPP 2014 criteria.7

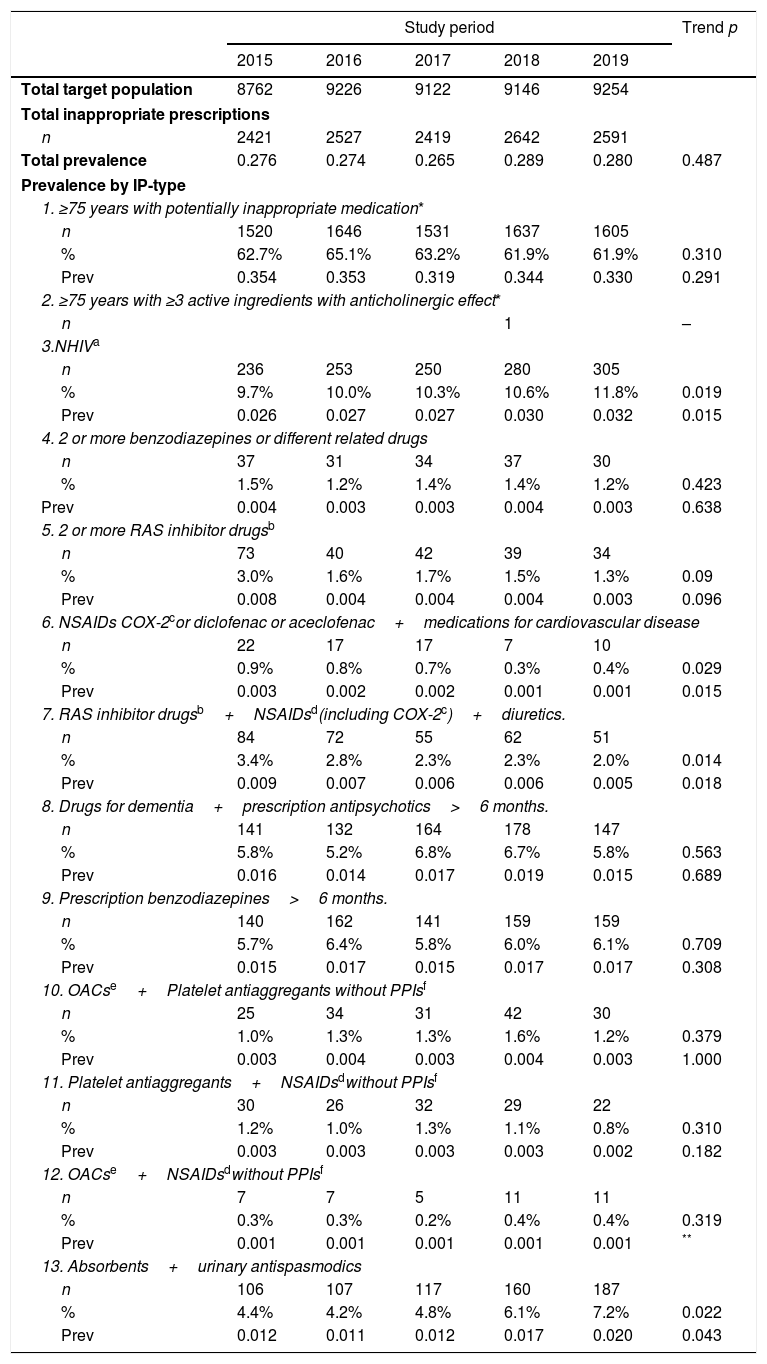

Prevalence of inappropriate prescribing, trends 2015–2019. Health Department València-Clinic-Malvarrosa.

| Study period | Trend p | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | ||

| Total target population | 8762 | 9226 | 9122 | 9146 | 9254 | |

| Total inappropriate prescriptions | ||||||

| n | 2421 | 2527 | 2419 | 2642 | 2591 | |

| Total prevalence | 0.276 | 0.274 | 0.265 | 0.289 | 0.280 | 0.487 |

| Prevalence by IP-type | ||||||

| 1. ≥75 years with potentially inappropriate medication* | ||||||

| n | 1520 | 1646 | 1531 | 1637 | 1605 | |

| % | 62.7% | 65.1% | 63.2% | 61.9% | 61.9% | 0.310 |

| Prev | 0.354 | 0.353 | 0.319 | 0.344 | 0.330 | 0.291 |

| 2. ≥75 years with ≥3 active ingredients with anticholinergic effect* | ||||||

| n | 1 | – | ||||

| 3.NHIVa | ||||||

| n | 236 | 253 | 250 | 280 | 305 | |

| % | 9.7% | 10.0% | 10.3% | 10.6% | 11.8% | 0.019 |

| Prev | 0.026 | 0.027 | 0.027 | 0.030 | 0.032 | 0.015 |

| 4. 2 or more benzodiazepines or different related drugs | ||||||

| n | 37 | 31 | 34 | 37 | 30 | |

| % | 1.5% | 1.2% | 1.4% | 1.4% | 1.2% | 0.423 |

| Prev | 0.004 | 0.003 | 0.003 | 0.004 | 0.003 | 0.638 |

| 5. 2 or more RAS inhibitor drugsb | ||||||

| n | 73 | 40 | 42 | 39 | 34 | |

| % | 3.0% | 1.6% | 1.7% | 1.5% | 1.3% | 0.09 |

| Prev | 0.008 | 0.004 | 0.004 | 0.004 | 0.003 | 0.096 |

| 6. NSAIDs COX-2cor diclofenac or aceclofenac+medications for cardiovascular disease | ||||||

| n | 22 | 17 | 17 | 7 | 10 | |

| % | 0.9% | 0.8% | 0.7% | 0.3% | 0.4% | 0.029 |

| Prev | 0.003 | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.015 |

| 7. RAS inhibitor drugsb+NSAIDsd(including COX-2c)+diuretics. | ||||||

| n | 84 | 72 | 55 | 62 | 51 | |

| % | 3.4% | 2.8% | 2.3% | 2.3% | 2.0% | 0.014 |

| Prev | 0.009 | 0.007 | 0.006 | 0.006 | 0.005 | 0.018 |

| 8. Drugs for dementia+prescription antipsychotics>6 months. | ||||||

| n | 141 | 132 | 164 | 178 | 147 | |

| % | 5.8% | 5.2% | 6.8% | 6.7% | 5.8% | 0.563 |

| Prev | 0.016 | 0.014 | 0.017 | 0.019 | 0.015 | 0.689 |

| 9. Prescription benzodiazepines>6 months. | ||||||

| n | 140 | 162 | 141 | 159 | 159 | |

| % | 5.7% | 6.4% | 5.8% | 6.0% | 6.1% | 0.709 |

| Prev | 0.015 | 0.017 | 0.015 | 0.017 | 0.017 | 0.308 |

| 10. OACse+Platelet antiaggregants without PPIsf | ||||||

| n | 25 | 34 | 31 | 42 | 30 | |

| % | 1.0% | 1.3% | 1.3% | 1.6% | 1.2% | 0.379 |

| Prev | 0.003 | 0.004 | 0.003 | 0.004 | 0.003 | 1.000 |

| 11. Platelet antiaggregants+NSAIDsdwithout PPIsf | ||||||

| n | 30 | 26 | 32 | 29 | 22 | |

| % | 1.2% | 1.0% | 1.3% | 1.1% | 0.8% | 0.310 |

| Prev | 0.003 | 0.003 | 0.003 | 0.003 | 0.002 | 0.182 |

| 12. OACse+NSAIDsdwithout PPIsf | ||||||

| n | 7 | 7 | 5 | 11 | 11 | |

| % | 0.3% | 0.3% | 0.2% | 0.4% | 0.4% | 0.319 |

| Prev | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | ** |

| 13. Absorbents+urinary antispasmodics | ||||||

| n | 106 | 107 | 117 | 160 | 187 | |

| % | 4.4% | 4.2% | 4.8% | 6.1% | 7.2% | 0.022 |

| Prev | 0.012 | 0.011 | 0.012 | 0.017 | 0.020 | 0.043 |

n: Number of inappropriate prescriptions. Trend p: Significant when p<0.05. IP-type: Specific type of inappropriate prescriptions. %: Percentage of an IP-type. Prev: Prevalence: number of inappropriate prescriptions divided by the corresponding population.

The indicator of IP prevalence was calculated as the quotient between the sum of IPs, overall or by specific type, and the number of patients identified as CCPs in the health department. Patients in the denominator for IP-type 1 and IP-type 2 were restricted to those aged ≥75 years, as this limit is part of the definition of these IP-types. The result is expressed per patient to avoid any confusion with the percentage of each IP-type to the total. Prevalence was calculated for each year of the period, time trends were examined using linear regression, and values of p<0.05 were considered statistically significant.

The data sources were as follows: the Valencian Health Authority information systems (Abucasis-Gaia) for the numerator; and the Valencian Community Patient Classification System, using CRGs version V1.6 with the International Classification of Diseases 9th Rev., Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM), for the denominator.

Raw data were processed with Microsoft Access Office 365 version 2016, and time trends were estimated using the SPSS computer software package.

ResultsThe results are shown in Table 1. Overall, the most frequent IP was IP-type 1 (≥75 years of age with inappropriate medication), which accounted for two-thirds of the total. This was followed by IP-types 3, 8 and 9. IP-types 6 and 12 were the least frequent. One IP-type 2 was registered.

As regards IP-prevalence time trends across the period, the total prevalence ranged from 0.276 (2015) to 0.289 (2018), without a statistically significant trend (p=0.487). While IP-type 1 also remained stable throughout (p=0.291), some IP-types displayed statistically significant time trends, with IP-types 3 and 13 rising, and IP-types 6 and 7 falling. Other trends were not statistically significant, and the prevalence indicators and percentages remained stable or fluctuated, except for IP-type 5 which showed a non-significant downward trend.

DiscussionThe IP prevalence and its time trends in a health department during 2015–2019 are reported, using an indicator composed of 13 types of inappropriate prescriptions identifiable in routine health information systems. The study population, comprising the department's complete set of CCPs as defined by CRG criteria, was mostly composed of elderly persons (75%≥65 years of age).

Our results show that during the study period, most IP affected persons aged 75 years or over, with no favourable trend in evidence across the period. Furthermore, some IP-types displayed unfavourable or unchanging trends.

The overall IP prevalence observed in our study was within the limits described by Delgado Silveira et al. for the IP prevalence in the community1 (see above). Considering some recently published Spanish papers, Hernández-Rodriguez et al. with information from the Computerised Database for Pharmacoepidemiologic Studies found important increases in some therapeutic subgroups, such as proton-pump inhibitors, statins and psychotropic drugs along 2005–2015, suggesting the need of studying prescription appropriateness12; Nuñez-Montenegro et al. studied IP in patients older than 65 years in a health district of Malaga, finding that IP prevalence for one or more STOPP/START criteria was 73.6%13; and Rogero-Blanco et al. described IP prevalence in primary care among patients aged 65–75 years in Andalucia, Aragon and Madrid, detected by an electronic clinical decision support system, showing that IP was present in 57.0% and 72.8% of the patients according to STOPP and Beers criteria, whereas 42.8% meet partially the START criteria.14 It must be borne in mind that, since IP prevalence varies with the methods and criteria used, the period studied, and the population characteristics and age groups covered, comparisons are extremely difficult. Even so, these studies and the one by Delgado Silveira et al.,1 nonetheless highlight the currently high prevalence of this problem.

In the health department studied, the time trends of IP prevalence indicate a persistent problem. Thus, continuous surveillance along time is needed, both overall and by specific type of inappropriate prescription. Which is possible as the data needed for the calculation of the indicator can be obtained from the routine information systems of the Valencian Health Authority.

Ascertaining the IP prevalence would make it possible to guide and evaluate interventions in the health department targeted at optimising prescribing, enhancing healthcare quality for elderly and CCPs in general, and also reducing pharmaceutical expenditure.15

In the following stages of this study, data collection will be extended up until 2021 to include the COVID-19 pandemic period. In addition, analyses will consider the characteristics of the patients (gender, age, CRG), and the designated health areas (zonas básicas de salud) to which they belong.

ConclusionsIn the present study, the prevalence of IP is an important and persistent problem among the elderly and CCPs, especially in the oldest patients. Therefore, its continuous surveillance with appropriate indicators is needed as well as suitable interventions to optimise prescribing.

Authors’ contributionsAll authors have made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the study, analysis and interpretation of data. PPC and JLTM obtained the data. PPC drafted the article. All authors revised critically the manuscript and contributed to it, and have approved the final version to be submitted.

Ethical considerationsThis study was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the Health Department ‘València-Clínic-Malvarrosa’ (25/05/2017) and classified by the Agencia Española de Medicamentos y Productos Sanitarios (AEMPS) under the code PPC-PRE-2017-01.

FundingThis research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial or not for profit sectors.

Conflict of interestAll authors declare no conflicts of interest.

The authors would like to express their gratitude for the help and support received from the following: information systems of the Valencian Health Authority (Conselleria de Sanitat Universal i Salut Pública); Medical Direction of the Health Department ‘Clinico-Malvarrosa; Primary Care Pharmacy Area of the University Clinical Hospital; the Emergency Department and the primary care health professionals in the Health Department; as well as Elena Pardo, Ana Muñoz and Laia Buigues.