The number of hospital admissions related to suicide attempts is increasing. Involuntary treatment of psychiatric disorders has always been controversial, and this issue can be particularly sensitive in case of suicide behaviour. The aim of this study was to analyse variables associated with involuntary and voluntary legal status on admission of suicidal ideation and suicide attempt in real practice.

MethodThe MacArthur Competency Assessment Tool for Treatment (MacCAT-T) was administered to a group of patients (n=73) with suicide behaviour and different types of psychiatric admissions (voluntary and involuntary). Severity of depressive symptoms, suicidal ideation and intent, and insight level were also assessed. A discriminant analysis was used to determine the differences.

ResultsMacCAT total score and insight level were the best variables to discriminate both groups. Although the majority of admissions were adequately classified according to their decision-making capacity, our results show some discrepancies at hospital admission.

ConclusionsAlthough this situation can be partly due to mistakes of interpretations of legal criteria for involuntary psychiatric admission or an inappropriate assessment of capacity to consent, due to the complexity of suicidal behaviour, a review of the classic criteria will also need to be considered, in order to ensure adequate support and to propose appropriate assessment tools for psychiatric and forensic practitioners.

En los últimos años en nuestro país ha aumentado la frecuencia de los ingresos hospitalarios relacionados con intentos de suicidio. El tratamiento involuntario de los trastornos mentales siempre ha sido controvertido y este aspecto puede ser particularmente sensible en casos de conducta suicida. El objetivo de esta investigación es analizar las variables que diferencian a individuos ingresados de manera voluntaria e involuntaria en caso de conducta suicida en la práctica real.

MétodosFue administrada la escala Mac Arthur para valoración de la competencia de tratamiento (MacCAT-T) entre un grupo de pacientes (n=73) con conducta suicida y diferentes tipos de ingreso (voluntario e involuntario). Se evaluó también la severidad de los síntomas depresivos, el nivel de ideación e intención suicida y el insight. Para conocer las diferencias se realizó un análisis discriminante.

ResultadosLas variables que mejor discriminan son la puntuación en la escala MacCAT y el nivel de insight. A pesar de que la mayoría de los casos fueron adecuadamente clasificados con relación a la competencia que presentaban, nuestros resultados muestran discrepancias en la modalidad de ingreso.

ConclusionesA pesar de que esta situación puede deberse a errores en la interpretación de los criterios legales de internamiento involuntario o de la valoración de la competencia, es posible también que la complejidad de la conducta suicida haga necesario revisar los criterios clásicos de valoración de la capacidad con objeto de asegurar una base adecuada y de proponer instrumentos de valoración específicos para psiquiatras y médicos forenses.

The growing frequency of suicidal behaviour and changes in the healthcare model mean that evaluating competence for consenting to hospitalisation for psychiatric disorders has also come to be more frequent in this type of behaviour. Suicide has become the main external cause of death, with a mortality rate that reached 7.68/100,000 inhabitants: it is now the leading external cause of death for individuals 25–34 years old according to the Spanish National Statistics Institute and is the first total cause for men in this age range.1 Even so, it is possible that there are differences based on the means of information used. Medical examiner information has been shown to be highly useful for this evaluation. Efforts are being made in various clinical and forensic settings to improve our knowledge of suicidal behaviour.2,3

Suicidal ideation or behaviour has become one of the main reasons for consultation in the general emergency care area, with an estimated prevalence of 4.4% for suicidal ideation and of 1.5% for suicide attempts.4 Hospitalisation rates of between 6.5% and 36.5%, depending on the attention received, have been reported.5 We have found no epidemiological data on the number of hospital admissions of an involuntary legal nature. However, the factors involved in the decision to hospitalise an individual and their legal nature are not always based on standardised criteria.6

In our legal system, involuntary hospitalisations are regulated in accordance with Spanish Law 41/2002, the basic indications on patient autonomy, and with Article 763 of Law 1/2000 of 7 January, on Civil Procedure. As defined in this basic legislation, hospitalisation due to mental disorder can be voluntary or involuntary.7

Voluntary hospitalisation occurs in the cases in which the individual is competent to reach a decision and acts freely guided by a physician, generally a psychiatrist. In such cases, there is no legal intervention. In the case of individuals that are not capable of granting valid consent, once the physician has indicated the need for hospital confinement – whether on an emergency or normal basis – the regulations require authorisation or confirmation by a judge for already performed emergency hospitalisation, after examination of the individual in question, with a report from the prosecution and from a prosecution-designated physician. In practice, this report usually falls to the medical examiner.8

In view of this regulation, consent is irrelevant when the patient is unable to make decisions, in the opinion of the physician in charge of the healthcare. Likewise, Article 763 of Law 1/2000 of 7 January, on Civil Procedure, specifies the requisite for involuntary hospitalisation due to mental disorder: that the individual be incapable of deciding for him- or herself. In medical-legal terms, this translates to the existence of psychopathological alterations that limit the capacity of acting with respect to the decision about hospitalisation and, consequently, limit the validity of the patient's consent.

Classically, the primary psychopathological alteration that justifies the absence of valid consent for hospitalisation due to mental disorder has been considered to be the alteration of the individual's thought content and judgement of reality; such an alteration makes the person affected incapable of adequate understanding of their situation and, consequently, invalidates their ability to consent.9

However, in suicidal behaviour we find ourselves facing psychopathological alterations that impact essentially the area of affect, without a primary alteration of the patient's cognitive and comprehension abilities. This means that a careful study of the competence of individuals whose hospitalisation is proposed is required. Controversies or difficulties are often present in this type of cases.10–12

The objective of this research was to ascertain the true practice of evaluating competency in this type of individuals and to analyse the variables associated with the classification of such individuals (voluntary and involuntary status) and the discrepancies that might arise.

MethodsThis was a 6-month observational study on a sample of 80 patients admitted for suicidal ideation or behaviour to either of 2 provincial units of mental health hospitalisation in the south of Spain belonging to the public healthcare system. The study was approved by the applicable Ethics Committee. All the cases had made a suicide attempt or had suicidal ideation as the main reason for hospitalisation. Subjects with psychotic symptoms or cognitive deterioration were excluded, as were children. All subjects were requested to sign an informed consent document to participate and 7 declined. In our study, the cases were studied according to the type of hospital admission: individuals that had been considered competent to make decisions and consequently entered the hospital voluntarily, and subjects considered to be incompetent and thus candidates for involuntary hospitalisation.

The statistical study was performed using discriminant analysis. This technique makes it possible to detect independent variables associated with the 2 populations previously indicated. In our case, we wanted to ascertain which combination of variables discriminated the best between voluntary and involuntary hospital admission. This yields a discriminant function, a set of variables that correlate with belonging or not to each of the groups and effectively separate the individuals in the 2 groups. Using Wilks’ lambda test of the discriminant function, we verified that a set of variables is significant in appropriately discriminating between both groups. In addition, this discriminant function serves to reclassify the cases based on the function obtained and allows us to classify future cases when the group to which they belong is unknown.

The principal variable that we measured in the 2 groups was the capability to give consent, using the MacArthur Competence Assessment Tool for Treatment (MacCAT-T). This instrument consists of a structured interview to assess the capability of consenting to treatment13,14 based on the Appelbaum and Grisso criteria15,16 for assessing capacity. A version of the MacCAT-T has been translated to Castilian Spanish and validated.17 We currently find ourselves limited when it comes to estimating competence to decide using scales or semi-structured interviews. The MacCAT-T interview was not designed bearing in mind the specific characteristics of patients with suicidal ideation or intention. This interview emphasises cognitive and intellectual functions and cannot properly discriminate distortions that may be produced by the emotional or affective state. However, it is the instrument that has been most frequently used in the various studies. This might represent a source of error.

Because these were cases related to suicidal behaviour, we wanted to see whether the affective state or the level of suicidal ideation or intention contributed to one or the other type of hospital admission. For this reason, the Beck Scale for Suicidal Ideation was used to assess ideation and intention,18,19 depressive symptoms were measured using the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale,20 and the level of insight was assessed using the Schedule for the Assessment of Insight-Expanded (SAI-E).21 We analysed the differences observed between the initial assessment and the main associated variables that we detected.

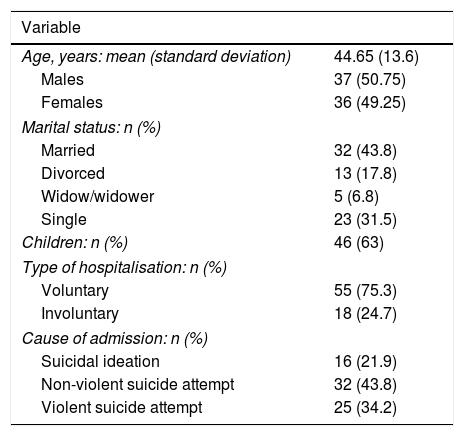

ResultsSociodemographic characteristics and those related to hospitalisation are shown in Table 1. Of the total hospital admissions, 75.3% were voluntary, while 24.7% were involuntary. The majority of these admissions (43.8%) corresponded to non-violent suicide attempts.

Sociodemographic characteristics.

| Variable | |

|---|---|

| Age, years: mean (standard deviation) | 44.65 (13.6) |

| Males | 37 (50.75) |

| Females | 36 (49.25) |

| Marital status: n (%) | |

| Married | 32 (43.8) |

| Divorced | 13 (17.8) |

| Widow/widower | 5 (6.8) |

| Single | 23 (31.5) |

| Children: n (%) | 46 (63) |

| Type of hospitalisation: n (%) | |

| Voluntary | 55 (75.3) |

| Involuntary | 18 (24.7) |

| Cause of admission: n (%) | |

| Suicidal ideation | 16 (21.9) |

| Non-violent suicide attempt | 32 (43.8) |

| Violent suicide attempt | 25 (34.2) |

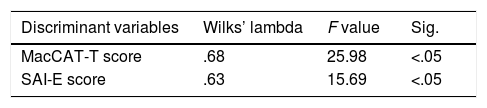

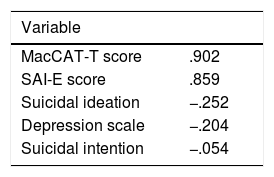

A discriminant function was obtained with the variables MacCAT-T score and level of insight, which was considered statistically significant (P<.05) (Table 2). This result implies that both variables are the predictors that best discriminate between the individuals belonging to each group, competent and incompetent. The intensity of the depressive symptoms or the level of suicidal ideation or intention were not significant and did not help to differentiate between voluntary and involuntary admissions. The coefficients of the variables in the discriminant function are shown in Table 3. We can consider that the MacCAT-T interview score and the level of insight efficiently separate the individuals observed in both groups. We reclassified the individuals in the study sample based on the 2 principal variables, obtaining the affiliation expected to each of the groups and the discrepancy with respect to the initial groups.

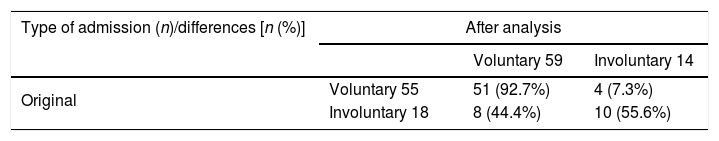

Concordance can be seen in the classification of the patients as voluntary or involuntary admissions in 83.6% of the original grouped cases. However, in light of these variables, 7.3% of voluntary hospitalisations were carried out in incompetent individuals, while 44.4% of the involuntary hospital admissions corresponded to competent individuals on the basis of the discriminant function. The results are shown in Table 4.

DiscussionOur study provides initial information on the real practice of assessing decision-making competence in hospital admission in cases of suicidal ideation or behaviour.

One limitation of this study is the sample size, restricted to 73 cases. However, this is a natural sample that allows an initial approximation to this issue, which is expected to become even more relevant in coming years.

We have found that the variables that differentiate the 2 groups in our sample are the level of insight and the total MacCAT-T interview score. Although there is appropriate concordance in a good part of the sample, the difficulty in assessing competence in this type of situations is revealed.

In our study, all the hospitalisations for suicidal behaviour were of an emergency nature. Most of the admissions were voluntary, without legal intervention. However, the number of cases in which the subject was considered incompetent for consenting to treatment and a judge and medical examiner were consequently required is not negligible.

As for the discordances found in classifying the individuals, these are produced in 2 directions, with different legal and clinical consequences.

Our results show fewer involuntary admissions than the originals, although the distribution is not homogenous. We find that approximately 7% of the cases in which the subjects are incompetent to give valid consent and are consequently candidates for involuntary hospitalisation were admitted voluntarily. The source of this disparity is unknown. The variables in our sample that allow assignation to this group are the total MacCAT-T interview score and the level of insight. However, both these variables are normally associated with psychotic processes or cognitive disorders.

Based on these criteria, one hypothesis is that the source of this error might be that the physician responsible for hospitalisation makes an inadequate assessment of competence. Yet there are few studies on competence to consent in subjects with suicidal behaviour. In previous publications, a rate of decision-making competence of 39% was reported, essentially associated with cognitive damage and the seriousness of the psychiatric disorder. It is more difficult to make assessments in cases in which the competence to consent is not altered by impairment of the ability to reason or understand; assessment consequences are also greater and produce the most disputes.22–25 In our study, we have excluded cognitive alterations to minimise this confounding factor.

As for ability to assess competence, psychiatrists have been considered to be highly reliable: substantial concordances with Kappa indexes of 0.6517 or 0.8718 have been reported; however, in cases of threshold capacity, the discordance is greater.26,27 Other studies present greater concordance in assessment of competent subjects, with false negative rates above 75% in general physicians in the general population with respect to psychiatrists.28 We have not found published data on psychiatrists’ capability to assess the validity of consent for hospitalisation in the specific instance of suicidal behaviour, even though an error in this matter can lead to incompetent patients making decisions for which they are not qualified.

Another hypothesis is that there are variables present in subjects with suicidal behaviour that are inadequately assessed by the standard model used for patients with cognitive alterations or alterations in judging reality. Likewise, there is no valid structured instrument that makes it possible to assess competence in patients with specific affective or emotional alterations that limit it. There may be factors besides insight and the parameters assessed using the MacCAT-T interview that strongly impact competence. Paradoxically, this type of behaviour is gaining more and more healthcare and epidemiological relevance.

The other discordance found lies in the cases in which involuntary hospitalisation occurs in spite of the fact that decision-making competence remains intact. In almost 45% of the involuntary hospital admissions, it is anticipated (considering the discriminant correlation) that the subjects should be admitted on a voluntary basis, as their competence for giving valid consent continues sound.

The risk of suicide and the possible medico-legal consequences have been considered to be one of the most common motives for involuntary hospitalisation even when the legal precepts for this are not fulfilled.29,10,30 It is clear that there is no scientific consensus about the factors involved and the best methodology for assessing competence to consent to treatment in suicidal behaviour.

Among the consequences of admitting a competent individual to hospital involuntarily, the infringement of the subject's liberty and autonomy to decide on her or his health as a protected legal asset stands out. There have been decisions (such as Sentence 141/2012 of the Second Division of the Supreme Court) that establish a violation of the right to personal liberty.31 In this sentence, the bases on which involuntary hospitalisation should be founded are reviewed. Among the indications for involuntary hospitalisation, 3 conditions are notable: the clinical entity of the disorder, lack of autonomy and the risk for the individual or for third parties that the clinical entity involves. The lack of autonomy implies that, due to the psychopathology present, the individual cannot give valid consent. In addition, the existence of a benefit for the patient and the proportionality of the measure have to be considered.

In the case of individuals who have made a suicide attempt or who present suicidal ideation, hospital admission is always justified as long as:

- •

it benefits the patient;

- •

it is needed to prevent the step to action or the repetition of the suicide attempt, with no other possible means of contention;

- •

the estimated risk is high because of pronounced suicidal ideation before or after self-destructive behaviour;

- •

in the case of involuntary commitment, a fourth criterion has to be met: that the basic mental state of the individual affects their ability to decide about hospitalisation.

In our study, an exclusion criterion was the presence of psychotic alterations, to avoid including cases with psychotic disorders in which there had been a suicide attempt (schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder and delusional disorder) as well as mood disorders with psychotic symptoms (depressive episode with psychotic symptoms). The reason for this exclusion was to eliminate the confounding factor of a base psychotic disorder, which might produce confusion about the capability of judging reality and, because of this, about the individual's self-management and competency to decide on treatment.

However, even without psychotic symptoms and considering only insight and the variables measured in the MacCAT-T interview, the predicted cases of a new classification are high, with excessive involuntary hospitalisation.

The consequence of allowing a patient with high suicide risk a voluntary discharge involves the possibility of damaging the assets of health and life, as well as the possibility of legal consequences arising from claims for healthcare malpractice, if the suicide should really happen. In our study, the variables associated with the level of ideation or suicidal intention and the degree of depression were not significant. There are probably other variables linked to suicidal behaviour that are not adequately assessed by the competence models in use to date with psychiatric patients.

The lack of systematised studies about this aspect and of specific assessment instruments is clear. In our case, we have not found any references to the use of the MacCAT-T scale as a means of support to assess competence in cases of suicidal behaviour. Competence assessment uses the criteria proposed by Appelbaum and Grisso as current consensus criteria. These involve assessing the 4 psychological domains to assess decision-making competence with respect to a specific medical intervention: understanding the disorder and the therapy options, appropriate appreciation of the interventions, the reasoning process that leads to the choice of one option or another, and the expression of the choice. These criteria imply that, after true and complete information about the clinical situation and the different treatment options has been offered, the subject is capable of adequately understanding and evaluating the characteristics of the disorder and the treatments offered, being able to reason acceptably in formal terms and to establish and express a choice about the treatment method selected. In this sense, changes have been proposed in the variable evaluation as the main alteration in disorders in which the primary impairment is affectivity and not thinking. The term “evaluation”, as it is used by these authors, involves appropriate assessment of the base disorder, of the various therapy proposals and of the consequences of one choice or another (that is, of the risks choosing represents).

With suicidal behaviour, the biggest difficulty is found in cases of patients at high risk of committing suicide but who, despite everything, seem to present adequate reasoning and understanding capabilities and consequently sufficient capacity to decide about their admission to psychiatric hospitalisation. Using classic criteria, these are cases in which the category of involuntary has possibly been used excessively. However, it is obvious that allowing a voluntary or agreed upon discharge to a subject with high suicidal ideation where imminent suicide can be expected goes against the principles of caution that should rule in medical actions. Some questions open: Are the Apelbaum and Griso criteria valid and applicable when thinking capability is unaltered and the sphere of affectivity is the main area impaired? Is the characteristic evaluation appropriately assessed in these subjects? Are conceptual instruments and adequate methods available to assess the evaluation that specific individuals who have attempted suicide or plan to attempt it make about their situation, treatment options and the risks entailed?

No option is completely free from risks of infringing protected legal principles. However, it is necessary to advance in studies and formulations that allow us to integrate appropriately the principle of patient autonomy with the clinician's objective duty of care and the legal guarantees required in involuntary admissions.

Our consequent objective is to extend the knowledge about the psychopathological elements that most often impact the decision-making competence of individuals who have attempted suicide without a primary psychopathology of thinking. We hope to provide clinicians and medical examiners with elements to decide when it comes to assessing the capacity for self-management in this type of cases, whose incidence is going to increase in the coming years.

Conflict of interestsNone declared.

Please cite this article as: Velázquez-Navarrete E, Gutiérrez-Rojas L. Competencia para decidir y tipo de internamiento en conducta suicida. De la teoría a la práctica. Rev Esp Med Legal. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.reml.2018.09.004