Issues surrounding coercive measures are an area of concern among mental health clinicians. Their use tends to be seen as unavoidable in the acute patient management in order to prevent harm to the patient or others. They should be used with caution, and only as a last resort. The lack of scientific literature about the effects of coercive interventions is limited, especially regarding patient perceptions. The “Coercion Experience Scale” (CES) is pioneer in the evaluation of the subjective experience of coercive measures.

MethodLinguistic and conceptual adaptation process into Spanish of the CES, using translation-back-translation methodology, with semantic and conceptual equivalence rating.

ResultsAll items of the final version received a type A (perfect) or B (satisfactory) equivalence assessment.

Discussion/conclusionsThe adapted version has good parity with the original version, guaranteeing proper measurement in samples of Spanish-speaking populations.

Las medidas coercitivas son un área de discusión entre profesionales de la salud mental. Su uso se entiende como inevitable en el manejo del paciente agudo con la finalidad de evitar daños a sí mismo o a otros. Sin embargo, deben usarse con precaución y únicamente como último recurso. La literatura sobre sus efectos perjudiciales es limitada, aún más respecto a las percepciones de los pacientes, siendo la Coercion Experience Scale (CES) pionera en la evaluación de la experiencia subjetiva de las medidas coercitivas.

MétodoProceso de adaptación lingüística y conceptual-traducción al español de la CES, mediante traducción-retrotraducción con escalas de equivalencia semántica y conceptual.

ResultadosLa versión final en español presenta una equivalencia tipo A (perfecta) o tipo B (satisfactoria) para todos sus ítems.

Discusión/conclusionesLa versión adaptada presenta una buena paridad con la original, permitiendo la medición adecuada en muestras de habla española.

Questions related to coercive measures remain a highly debated topic amongst mental health professionals. In spite of the ethical and safety issues regarding coercive measures, their use is still seen as inevitable for handling acute patients to prevent them from harming themselves or others.1 Moreover, the coercive measure that is selected and its effects vary greatly, reflecting the existence of powerful local effects.2

Non-coercive measures and de-escalation techniques are the intervention of choice when it comes to handling acute agitation and threatening behaviours.1 Coercive measures such as isolation or mechanical restraint must be used with caution and only as a last resort once other methods for handling the situation have failed.3 The least restrictive alternative is always recommended.4 The fact is coercive interventions are associated with an increased incidence of physical and psychological injury, both in patients and in healthcare professionals, and they have harmful short- and long-term effects on the patient/professional relationship.1

In our field there are studies that describe some of the harmful effects of coercive interventions,5 and legislation has been passed in this regard in recent years.6 Yet the lack of well-designed publications and random studies analysing the effects of isolation and mechanical restraint on a national and international level is, according to Sailas, “surprising and alarming”.7 The ethical and methodological difficulties have only been addressed quite recently.8 Patient complaints regarding coercive measures generally focus on subjective feelings of humiliation, punishment and traumatisation,9 but there are few instruments for evaluating these aspects. Many of them focus on non-psychiatric issues or only deal with mechanical restraint10 or the hospital admissions process11 or their use in the penitentiary system.12

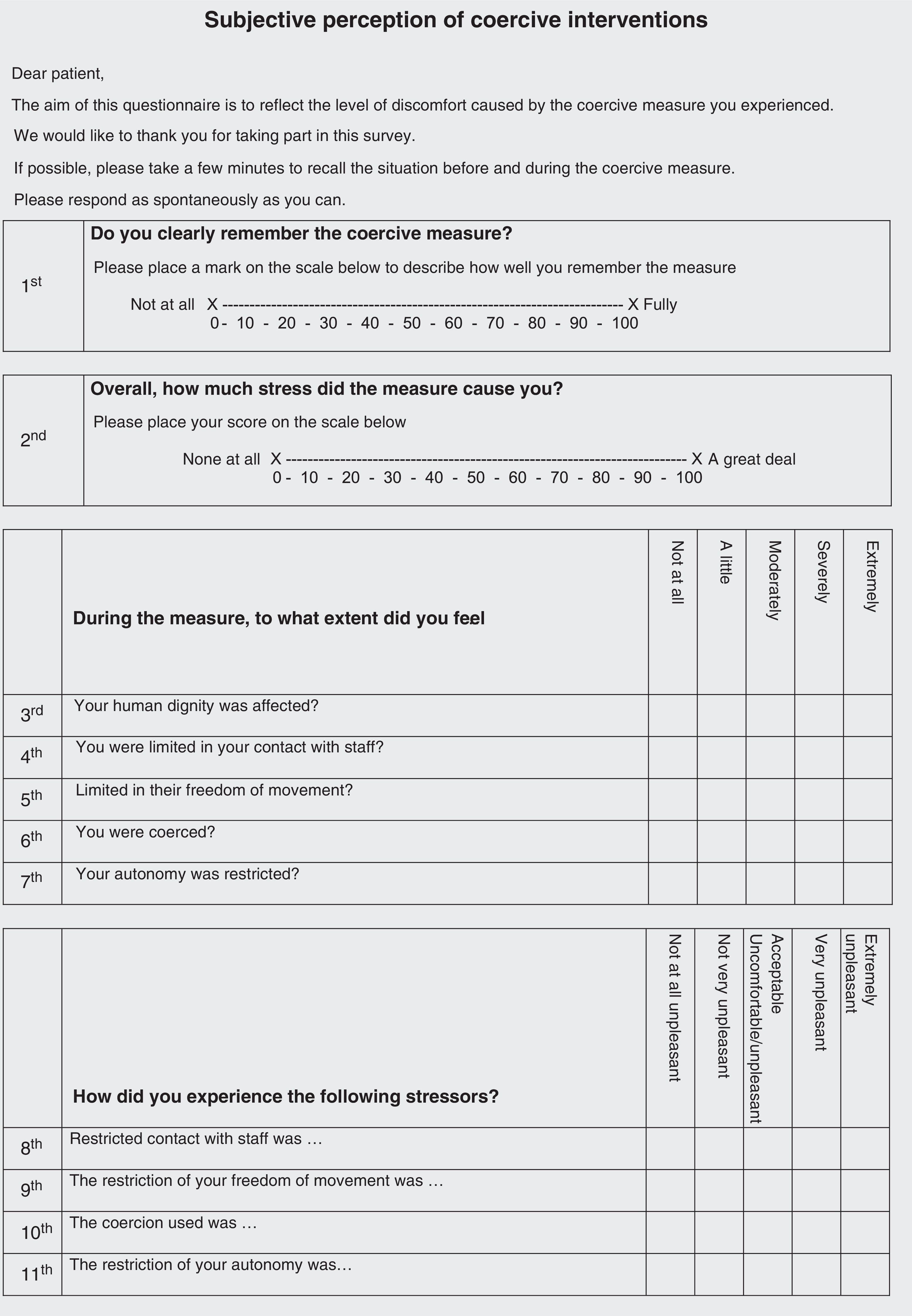

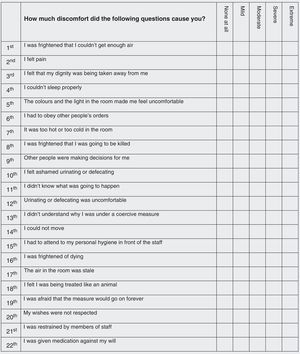

Bergk, Flammer and Steinert published the Coercion Experience Scale (CES) in 2010.13 The CES is an instrument for measuring the subjective experience of patients in coercive interventions, such as isolation or mechanical restraint. It can be used with patients who need support after coercive interventions or to compare the subjective experiences of various coercive interventions.14

The degree of restriction is evaluated for each human right (none/a little/moderate/severe/extreme), and except for “human dignity”, how it was experienced (acceptable/uncomfortable/unpleasant/very unpleasant/extremely unpleasant). The degree of restriction was proposed to reflect the objective conditions and the experience was proposed to reflect the subjective impact. The stressors were assessed on a Likert-scale (not stressful/mildly/moderate/severely/extreme).

The validity was evaluated by calculating correlation coefficients between the subscales and a visual analogue scale (VAS) that measured the total effect of the coercive measure, an instrument for measuring post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), patient satisfaction and the Impact of Event Scale (IES-R). Staff members assessed another VAS on the overall effect of the measure on the patient, which was used as an external point of reference. To estimate the risk of traumatisation induced by the coercive intervention, a regression of the total score on the PTSD screening score was carried out. After the analysis explaining the factors, 11 items with factor loadings under 0.50 were eliminated. Another item was eliminated after the analysis of each item separately. The psychometric properties of the 33 final items of the CES showed satisfactory validity and reliability. The cut-off point for detecting PTSD was defined as 70 points on the CES scale.

The CES scale pioneered the evaluation of the subjective experience of coercive measures in psychiatry. It is the first instrument that measures psychological impact in a coercive psychiatric intervention, and it may become the landmark test in this field.

The process of adapting instruments from their original language into others is crucial for evaluating the reality of various geographical locations and for being able to unify and contrast results obtained throughout the world. Moreover, creating a scale is a very costly process. The CES was originally developed in German. We believe that translating it and adapting it in Spanish – one of the most widely spoken languages in the world – is a valuable task that would help provide better evidence on the different types of coercive interventions. A brief overview of the process of adapting the language and concepts of the CES to Spanish is discussed below.

MethodThe translation/back-translation method was used for the linguistic and conceptual adaptation of the CES following the test guides for translation and adaptation of the international testing commission.15 This technique, which has been used successfully in previous adaptations,16 corroborates the semantic and structural equivalence between the original items and those translated into Spanish. Two of the authors of the CES were contacted in order to obtain the original version of the CES in German. A German native and one of the authors (ELGD), a psychiatrist and forensic physician, translated the scale directly into Spanish. In accordance with the recommendations of the international test commission,15 the translators were sufficiently qualified in the language and understood the target culture, thus ensuring that the subtleties and tones of the original scale were maintained.

To double-check the first Spanish translation, three external proofreaders evaluated the original translation independently. These proofreaders indicated the items that could be improved semantically or grammatically or both, and they worked with one of the original translators (ELGD) to reach a consensus on the version. Once they agreed on a version, a bilingual German translator re-translated the CES back into German. This translator was not familiar with the German original. This ensured the reliability of the back translation.

Once this translation was complete, the document was sent to one of the original authors of the CES (TS). This author compared the new German version with the original and classified the items based on how they matched the original items. This classification was done using a ranking that measured two basic characteristics: semantic and conceptual matching. This way, the re-translated items that matched the original items both semantically and structurally were classified as “Type A”. Those which had a satisfactory conceptual match but which differed in one or more words from the original version were tagged as “Type B”. Items that retained the original meaning but did not have a satisfactory conceptual match were classified as “Type C”. “Type D” items were those where there was no semantic or structural match between the original and the back translation.

Items that did not have a good equivalence with the original version (Type C or D) were re-analysed by the research group to find a satisfactory version accepted by consensus. The items that were modified were back-translated again by an independent translator.

Lastly, TS once again compared the original scale and the back-translated scale to confirm that their equivalence had increased due to the adjustments made in the items brought into question.

ResultsThe first evaluation of the equivalence between the original items and the back-translation to the Spanish revealed a high degree of “Type A” equivalence in 8 of the 33 back-translated items (24.2%), “Type B” in 17 items (51.5%), “Type C” in 4 items (12.1%), and “Type D” in the other 4 (12.1%).

Alternative Spanish translations were done for the items classified as C and D equivalences. The new versions of these items were then put through the back-translation process and obtained “A” or “B” equivalences. In the final Spanish version of the CES shown in Fig. 1, 14 of the items had a “Type A” equivalence (42.4%), and 19 items had a “Type B” equivalence (57.5%).

Discussion/conclusionsThe Spanish version of the CES is the result of the process of translating/back-translating the original German scale, with an appropriate linguistic and conceptual adaptation. Maintaining a conceptual and semantic equivalence ensures the original degree is maintained of the validity and functionality of the instrument.

This adaptation of the scale for the Spanish-speaking population means there is no longer an instrument lacking with these characteristics, and its psychometric validation in the future will make it possible to have reference values in the Spanish population in the future. Thus Spanish speaking populations will have a resource for estimating the subjective experience of patient coercion, which may eventually be compared with other patients around the world.

Conflicts of interestThere are no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Gómez-Durán EL, Martin-Fumadó C, Santonja R, Campillo M, Arimany Manso J, Bergk J, et al. Adaptación lingüística y conceptual al español de la Escala de experiencia de coerción. Rev Esp Med Legal. 2016;42:24–29.