To determine the frequency of palliative sedation in our unit, to know the characteristics of the patients to whom it was applied and to describe the therapeutic measures that were employed.

Material and methodsObservational retrospective study of all patients who were admitted and died in the Palliative Care Unit of the Puerta del Mar University Hospital (Cádiz, Spain) between January 1st 2013 and December 31st 2013. All of them were oncology patients. The data were obtained from the medical records. A descriptive analysis of all the collected variables was performed.

ResultsA total of 290 patients were admitted; 92 died (31.7%). Among the latter, sedative treatment was applied to 25 (27.2%). About half of these were male (52.0%) and their mean age was 61.7 years (SD 10.2). The most common refractory symptom was dyspnoea (36.0%). In all cases midazolam was used for sedation, alone or in combination with levomepromazine. Its route of administration was intravenous or subcutaneous.

ConclusionsThe clinical profile of patients requiring palliative sedation was: male, of 62 years of age, oncological and with dyspnoea as refractory symptom. The most employed drug was midazolam.

Los objetivos del presente estudio fueron determinar la frecuencia de la sedación paliativa en nuestra unidad, conocer las características de los pacientes a los que se les aplicó y describir las medidas terapéuticas empleadas.

Material y métodoEstudio retrospectivo observacional de todos los pacientes que ingresaron y fallecieron en la Unidad de Cuidados Paliativos del Hospital Universitario Puerta del Mar de Cádiz entre el 1 de enero y el 31 de diciembre de 2013. Todos los pacientes atendidos fueron oncológicos. Los datos se obtuvieron mediante el análisis de historias clínicas. Se realizó un análisis descriptivo de las variables recogidas.

ResultadosIngresaron 290 pacientes, de los que fallecieron 92 (31,7%). Se aplicó tratamiento sedativo a 25 (27,2%). Alrededor de la mitad de estos fueron varones (52,0%) y su edad media fue 61,7 años (DE 10,2). La sintomatología refractaria más frecuente fue la disnea (36,0%). En todos los casos se empleó midazolam, solo o en combinación con levomepromacina, para conseguir la sedación.

ConclusionesEl perfil clínico del paciente que requiere sedación paliativa es el de un varón de 62 años de edad media, oncológico y con disnea como síntoma refractario. El midazolam es el fármaco más empleado y la vía de administración es intravenosa y subcutánea.

The World Health Organisation defines palliative care as “an approach that improves the quality of life of patients and families facing the problems associated with life-threatening disease through the prevention and relief of suffering by means of early identification and careful assessment and treatment of pain and other basic psychological and spiritual problems”.1

Social demand in palliative aspects of medicine has increased markedly since the late XX century. Some of triggering factors include the progressive ageing of the population and an increased number of patients with cancer or chronic and degenerative diseases. As a result, the number of people facing the dying process is increasingly high. Although palliative treatment is often the only realistic option, most resources are allocated to curative treatments of relatively high cost and limited efficacy.2

People diagnosed with cancer and other serious chronic diseases are very likely to experience multiple and complex symptoms that entail comprehensive and continuous evaluation and the use of appropriate treatment. This involves patients with the potential need for palliative care to alleviate symptoms, improve quality of life and provide a death without suffering.3,4 Thus the process of dying does not have to be an agonising wait for death, but a pain-free period during which patients’ welfare and peace of mind are always sought. In short, a period of time that allows patients to give and receive affection. Access to adequate care and support at the end of life is recognised by several authors as a basic human right.5,6

This concerns a situation in the final days, a progressive transition period between life and death that occurs at the end of many diseases. The process usually lasts a few hours or days, and most of the time, less than a week. In this situation, patients should ideally be in charge of decision-making and have the final say. Collaboration between the family and the medical staff seems to improve efficacy.7

In some cases, patients who are near death experience refractory symptoms that impede relief despite intensive medical treatments. This requires a treatment of last resort: palliative sedation.8 This is defined as a deliberate decrease in the patient's level of consciousness by administering appropriate drugs in order to prevent intense suffering caused by one or more refractory symptoms. It can be continuous or intermittent, and intensity is adjusted by looking for the minimum level of sedation that achieves symptomatic relief.9

Refractory symptoms are those that are intolerable for the patient, where the medical staff has conducted intensive therapeutic efforts to find a treatment that controls properly without compromising level of consciousness and with an acceptable risk–benefit relationship for a reasonable period of time.10 That said, we must differentiate them from a difficult symptom, which is one for which adequate control requires an intensive therapeutic intervention, beyond the usual means, both pharmacologically as well as instrumentally or psychologically. Thus, sedation should not be considered as a routine therapeutic option to manage symptoms that are difficult to control, such as neuropathic pain, but which are not refractory.11

Some refractory symptoms that can require sedation are delirium, dyspnoea, pain, seizures and psychological or existential problems. The drug of choice in palliative sedation is midazolam, administered by continuous infusion.12 Other drugs include levomepromazine, phenobarbital and propofol, which also can be mixed with drugs used for other purposes.13,14

As mentioned above, palliative sedation as a therapeutic measure requires the consent of the patient or the family. Patients should be able to decide according to their own values and priorities, which may not coincide with those of the doctor. This is achieved only through a process of dialogue and collaboration in which efforts are made to take patients’ wishes and values into account. Moreover, it should never be done based on the initiative of the family or of the health professionals under the subjective pretext that the patient is suffering a lot.15 This consent does not need to be formalised in writing, but must be recorded in the medical record or, where appropriate, in official documents for this purpose, such as the recording of living wills.16,17 The decision must be made, therefore, by the patient and shared with health professionals. Numerous studies show that shared decision-making improves patient satisfaction, treatment adherence and outcomes, and healthcare costs.18–20

The objectives of this study were to determine the frequency of palliative sedation in our setting and the clinical characteristics of deceased patients who were given a sedative treatment, and to describe the therapeutic measures which were used in patients in their final days, especially in regard to the need for symptomatic treatment or sedation.

Materials and methodsRetrospective observational study. We included all patients who were admitted and died in Puerta del Mar University Hospital's Palliative Care Unit in Cádiz during the period from 1 January 2013 to 31 December 2013. There were no exclusion criteria. All patients treated in our unit were cancer patients with advanced disease. The data were obtained by analysing hard copies of medical records and through the Diraya Specialist Care (DAE) electronic medical record system, in accordance with our site's confidentiality protocols.

The variables analysed were age, sex, symptoms on admission, use of symptomatic treatment, symptom that justified the need for sedation, evidence of consent in medical record, underlying cancer, use of palliative sedation, drugs used for sedation and route of administration. Level of distress was defined as the psycho-emotional state of discomfort that is sometimes accompanied by physical symptoms, and which in palliative care is associated with end-of-life situations. A descriptive analysis was performed of all the variables. Continuous variables are expressed by mean and standard deviation, and categorical variables by frequencies and percentages. The data were processed and analysed in SPSS, version 20.

ResultsDuring the study period, 290 patients were admitted to the Palliative Care Unit; 92 of these patients died (31.7%), and they represent the series studied. The majority were men (n=62; 67.4%). The mean age was 68.2 years (SD=12.1). The most common symptoms on admission were dyspnoea (n=43; 46.7%) and delirium (n=28; 30.4%). Symptomatic treatment was given to all patients, with symptom control achieved in 72.8% (n=67). In the rest of the patients, symptomatic management was not effective, and sedative treatment was required for 25 patients (27.2%). In all these cases, consent was present in the medical record.

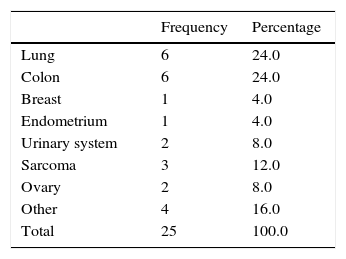

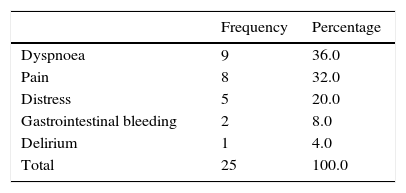

Amongst the patients who received palliative sedation there were 13 men (52.0%), and the mean age was 61.7 years (SD=10.2). The most common symptoms were refractory dyspnoea (n=9; 36.0%) (Table 1). The most common cancers were lung and colon (6 patients each; 24.0%) (Table 2). In one case the treatment sheet was missing in the medical record. In the remaining 24 patients, the drugs required for adequate control of symptoms were maintained (such as morphine or haloperidol), and midazolam was used, alone or in combination with levomepromazine (n=7; 29.2%), to achieve sedation. To this end the intravenous or subcutaneous routes were used in 11 patients each (45.8%) and both in 2 (8.3%).

The rate of palliative sedation amongst patients who died in our unit was 27.2%. In the studies published this parameter varies widely (from 1% to 72%), although with an average value of 25%, i.e. close to that which we observed. It should be noted that the studies on the subject were conducted at different periods of time, and the definitions used in the different studies are not homogeneous.21–23

In terms of age and sex, our results were consistent with the data observed in other studies regarding the use of palliative sedation in adult patients, aged between 60 and 70 years, who were mostly men.24 All patients included in the study were diagnosed with cancer, due to the characteristics of our unit. Although palliative medicine should be offered to cancer and non-cancer patients, at present most are cancer patients, and among these, as in our study, lung cancer is the most common.25

As regards refractory symptoms, dyspnoea is the most common, which is consistent with the literature consulted.10,21 It should be noted that there was a low number of patients in our study who had delirium (one case). We believe that delirium is a true diagnostic and therapeutic challenge, and requires evidence-based recommendations for the proper management of patients at the end of life.26 It is also important to note distress, which occurred in 5 of our patients. We now have more tools to control the physical symptoms, but the existential psychosocial dimension is a difficult area to approach, especially when the patients, during their illness, have developed strategies of denial or regressive behaviour that have been respected in accordance with the principle of autonomy.22

Finally, for patients requiring sedation, treatments were maintained that help to adequately control symptoms, but in order specifically to achieve adequate sedation, midazolam was used almost exclusively, in a minority of cases combined with levomepromazine. The drugs and routes of administration used resemble the results found in most of the literature consulted that suggest that benzodiazepines are the treatment of choice when considering sedation as a therapeutic option.27,28

The study has limitations. First, the information collected was limited. For example, the doses of drugs used in sedation, the existence of advance directives, and the time of evolution between the onset of sedation and the death of the patient were not included. Further, the groups with or without sedation were not compared. One study that is now under development by our group will focus particularly on the duration of sedation, the dose of the drugs, or the need to increase it. Second, this is a retrospective study, with the typical disadvantages of this type of design. However, it should be noted that it is not easy to carry out prospective studies of patients’ final days in which there is a good balance in the sensitivity and specificity of patient selection. It happens that patients included in prospective studies because they are apparently terminally ill far exceed the prognoses made at the start. In a similar vein it is normal to have patients who are excluded but who die within a short time without having gone through all the stages expected in the terminal phase. In both cases, prospective studies have a selection bias, as the best method to confirm a patient's terminal status is death. Based on the foregoing, there is an open debate on how to define the evidence in research into palliative care. It seems necessary to propose specific standards to adapt to the conditions, needs, expectations and limitations of this type of patient.29,30 Last, the generalisation of the results is limited by our unit's characteristics, in particular the fact that all of our patients are cancer patients.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Carmona-Espinazo F, Sánchez-Prieto F, López-Sáez JB. Nuestra experiencia en sedación paliativa como opción terapéutica en pacientes en situación clínica de últimos días. Rev Esp Med Legal. 2016;42:93–97.