A 41-year old female with a history of epilepsy, currently under treatment, substance abuse (cocaine, cannabis, alcohol), and migraine, presented to the hospital for drowsiness, asthenia, and generalised pain after consuming alcohol, ibuprofen, paracetamol, and quetiapine.

She was admitted to the Intensive Care Unit with the suspected diagnoses of paracetamol poisoning with multi-organ failure (hepatic, renal, neurological, and respiratory), left pneumothorax requiring chest drainage, positive for SARS-CoV-2 by PCR.

The process was oriented toward full-blown hepatitis and infusion with N-acetylcysteine, broad-spectrum antibiotic coverage, antifungal prophylaxis, deep sedation, and, in light of the need for a high levels of noradrenaline, treatment with methylene blue was also introduced to provide vasoactive support.

Despite the tratamiento that was initiated the patient presented liver failure and severe, persistent shock in a terminal, irreversible situation.

Case 2An 18-year-old male was admitted to hospital with the suspicion of drug overdose with quetiapine, with a history of major depressive disorder, as well as prior suicidal ideation and suicide attempts.

The blood test revealed a concentration of valproic acid of 828 ng/ml (range 40–100). Given the levels of valproic acid detected, coma, and hyperamonaemia, the decisión was made to initiated renal replacement therapy.

The patient was maintained under deep pseudoanalgesia with remifentanil and propofol. The latter was replaced by midazolam after 24 h. The patient presented with hypotension and was therefore administered a combination of adrenaline and double methylene blue at a dose of 40 ml/h, in light of refractory distributive shock, valproate, olanzapine, and quetiapine poisoning; acute pancreatitis, and suspected bronchoaspiration (covered with antibiotics).

His clinical situation evolved unfavourably with shock, that was refractory to all the measures undertaken, and multi-organ failure, after almost 72 h of hospital admission.

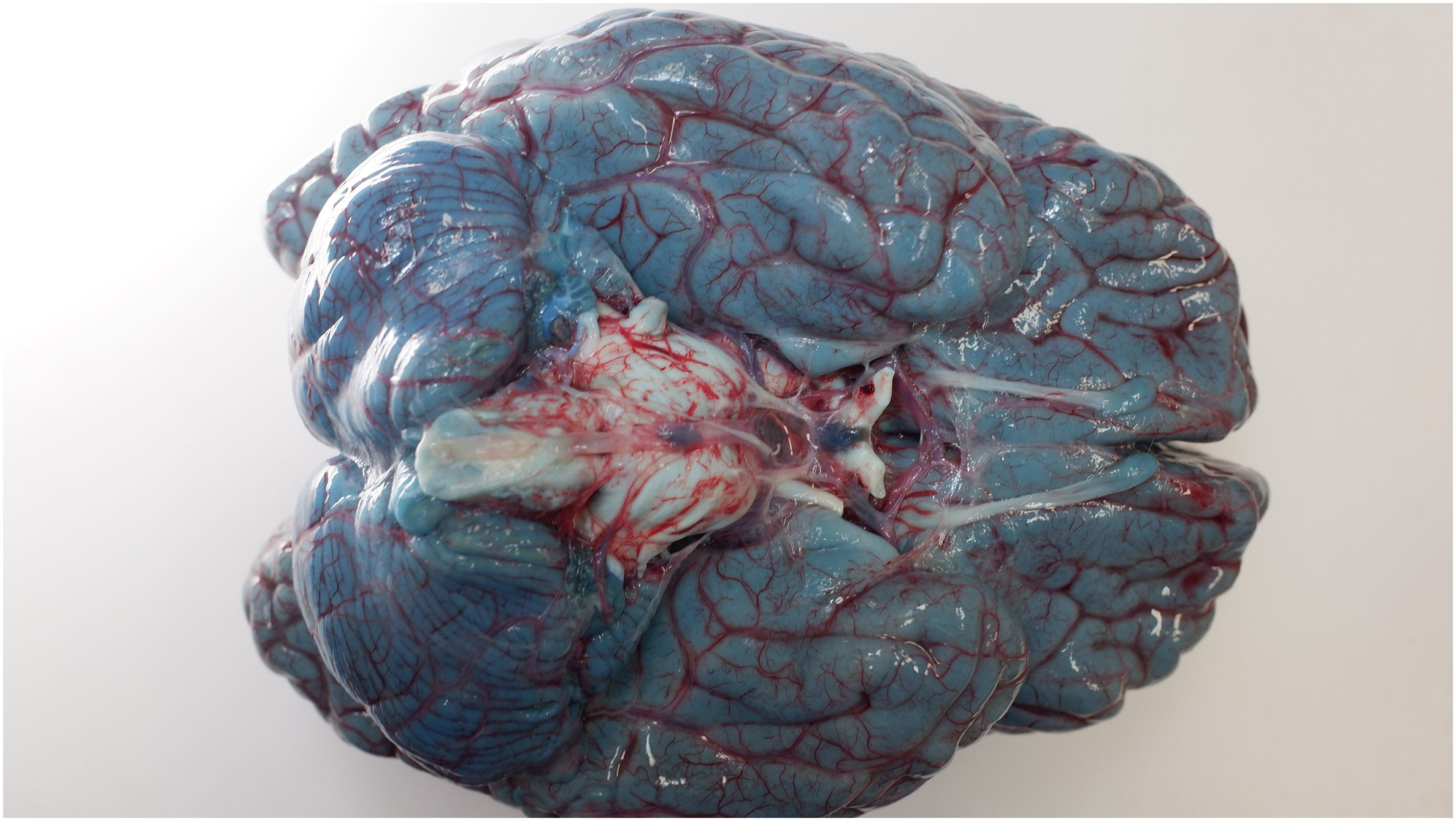

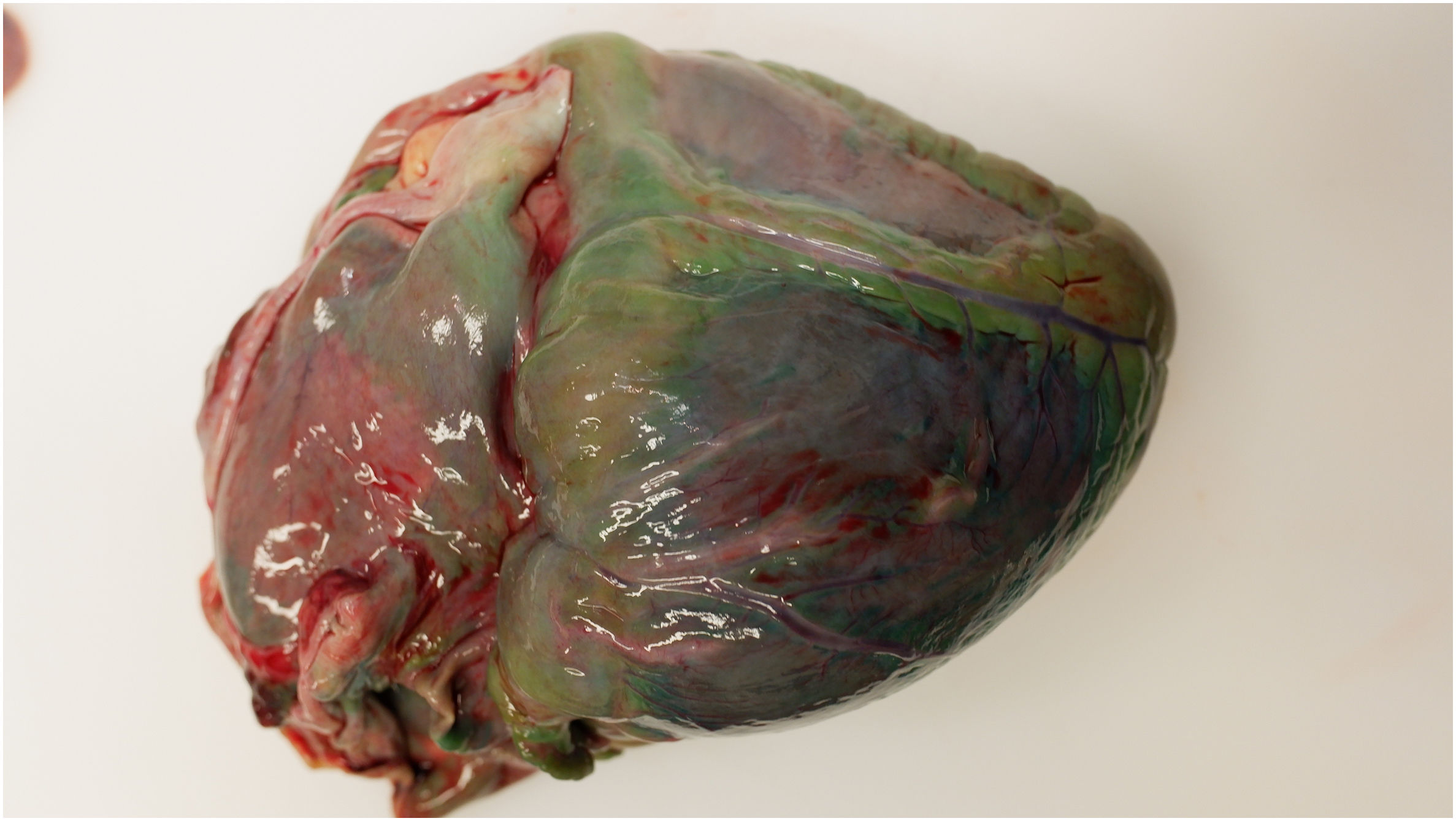

In both cases, a forensic autopsy was ordered given that they were violent deaths. The most noteworthy findings were the dark blue-green (“pistachio” green, “avatar” blue, turquoise) colouring of the organs, especially the brain (Fig. 1), heart (Fig. 2), liver, and kidneys, as a consequence of treatment with methylene blue, which causes a characteristic colouring.

DiscussionMethylene blue is a heterocyclic aromatic compound that turns blue under oxidising conditions and is colourless under reducing conditions. It is occasionally used as a vasopressor in severe catecholamine-refractory hypotension and has been reported to produce a blue-green staining of the brain and other organs after exposure to oxygen.1,2

It is a nitric oxide synthase and guanylate cyclase inhibitor that can be applied in a variety of clinical applications as an inotropic and vasoconstrictor. In addition, it has been used to treat methaemoglobinaemia, anaphylaxis, malaria, carbon monoxide poisoning, severe hepatopulmonary syndrome, and as a dye for microscope staining.3,4

The interest in this finding lies in establishing a postmortem differential diagnosis on autopsy with hydrogen disulphate poisoning, putrefaction, or Pseudomona aureginosa infection.

The authors thank Technicians specialising in forensic pathology from the Forensic Pathology Service of the Institute of Legal Medicine and Forensic Sciences of Catalonia.

Special thanks to Mrs. Celia Rudilla, librarian and documentalist at the Institute of Legal Medicine and Forensic Sciences of Catalonia.

Please cite this article as: Rueda Ruiz M, Crespo Alonso S, Carrillo Pintos J, Ortega Sanchez ML. Postmortem visceral staining due to methylene blue. Revista Española de Medicina Legal. 2024. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.remle.2024.04.003.