Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) are a promising new treatment for different types of cancer. The infectious complications in patients taking ICIs are rare.

Case reportA 58-year-old male who received chemotherapy consisting of pembrolizumab (PD-1 inhibitor) for esophagus squamous cell carcinoma one month before was admitted to the emergency room with shortness of breath soon after fiberoptic bronchoscopy, which was done for the inspection of the lower airway. A computed tomography of the chest revealed a progressive consolidation on the right upper lobe. Salmonella group D was isolated from the bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid culture. The fungal culture of the same clinical sample yielded Aspergillus niger; furthermore, a high titer (above the cut-off values) of Aspergillus antigen was found both in the BAL fluid and serum of the patient. Despite the effective spectrum and appropriate dose of antimicrobial treatment, the patient died due to disseminated intravascular coagulopathy.

ConclusionsAwareness of unusual pathogens in the etiology of pneumonia after ICI treatment may help to avoid underdiagnosis.

Los fármacos inhibidores de puntos de control inmunitario (ICI) son una nueva y prometedora opción de tratamiento para diferentes tipos de cáncer. Las complicaciones infecciosas en pacientes que toman ICI son poco frecuentes.

Caso clínicoUn varón de 58 años que recibió quimioterapia con pembrolizumab (inhibidor de PD-1) para un carcinoma de células escamosas de esófago hacía un año, ingresó en Urgencias por dificultad respiratoria poco después de realizarse una broncoscopia de fibra óptica para una inspección de las vías aéreas inferiores. La tomografía computarizada de tórax reveló una consolidación progresiva en el lóbulo superior derecho. Se aisló Salmonella grupo D en el cultivo del líquido de lavado broncoalveolar (LBA). En el cultivo de hongos de la misma muestra creció Aspergillus niger; además, se detectó antígeno (por encima de los valores de corte) de Aspergillus tanto en la muestra del LBA como en el suero del paciente. A pesar del espectro eficaz y la dosis adecuada del antifúngico utilizado, el paciente falleció debido a una coagulopatía intravascular diseminada.

ConclusionesEl conocimiento de patógenos inusuales en la etiología de la neumonía tras el tratamiento con ICI puede ayudar a evitar el infradiagnóstico.

Cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen 4 (CTLA-4) inhibitors, the programmed death-1 (PD-1), and programmed death-ligand (PD-L1) inhibitors are immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), a promising option for treating different types of cancer.16 ICIs block the apoptosis signal of cytotoxic T cells and lead to the destruction of malignant cells. Normal host tissues are exposed to autoimmune processes because of non-specific cytotoxic effects during ICIs treatment. This process is clinically named immune-related adverse events.4 While ICI therapy is not considered a risk factor for opportunistic infections, the risk of uncommon infections increases when receiving immunosuppressant therapy for immune-related adverse events.1,14 Herein, we report a fatal and unusual case of necrotizing pneumonia secondary to Salmonella and Aspergillus infection, after ICI therapy without a history of immunosuppressant therapy.

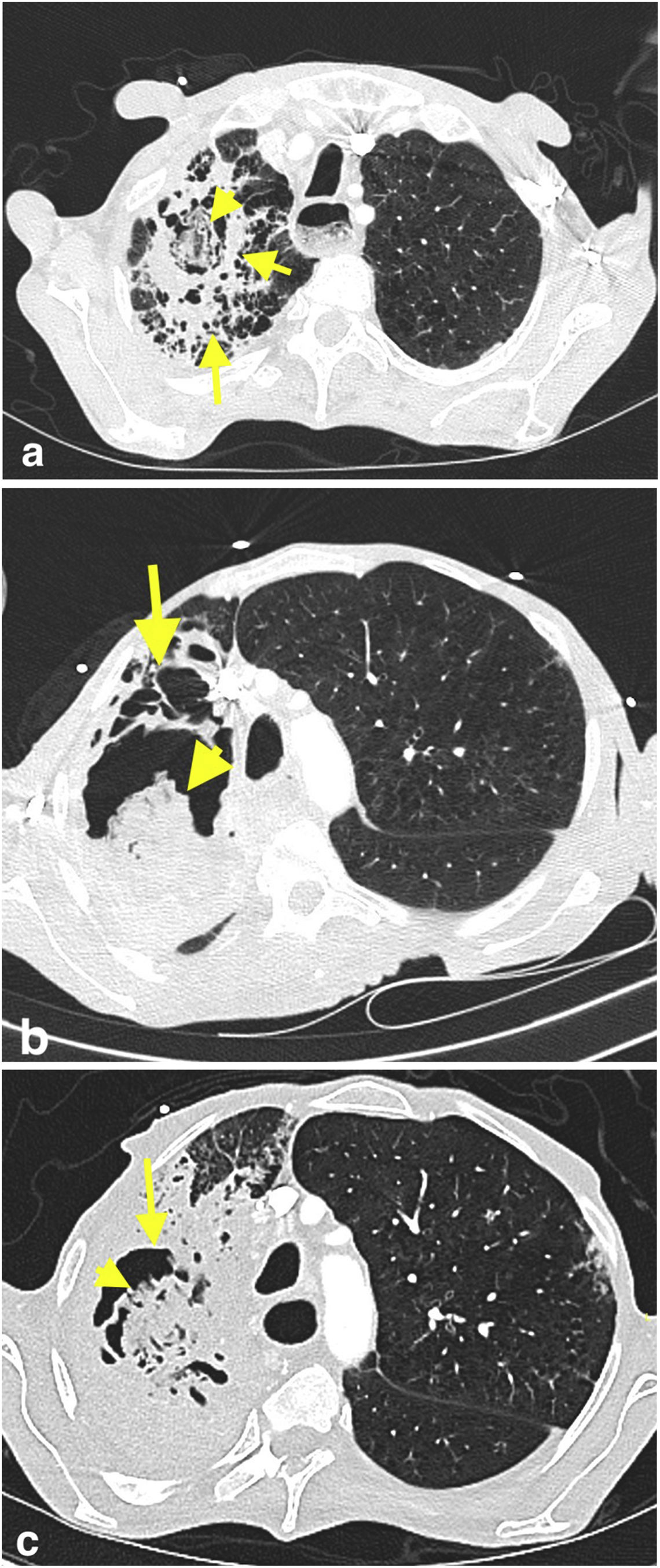

Case presentationA 58-year-old male was admitted to the emergency room (ER) with increasing shortness of breath, cough, and whitish sputum. His past medical history included esophagus squamous cell carcinoma with liver metastasis for which he started a treatment one year before with neoadjuvant chemotherapy and radiotherapy, right after an esophagectomy. The patient had received the fourth cycle of chemotherapy, consisting of m-FOLFOX (modified folinic acid, fluorouracil, and oxaliplatin), and pembrolizumab (PD-1 inhibitor) the month before, and had another ER visit due to shortness of breath and fever three weeks before the one in this case. Thoracic computed tomography (CT) revealed broad ground-glass opacities, nodular opacities, and fibrotic changes with a cavitary lesion that were not observed on thoracic CT the month before (Fig. 1a). With the diagnosis of community-acquired pneumonia, a treatment consisting of ampicillin-sulbactam (intravenous, 2g ampicillin+1g sulbactam, q.i.d) and clarithromycin (oral 500mg, b.i.d) was started; the patient had no antibiotic history in the previous three months. On the third day of the treatment, Salmonella group D (susceptible to ampicillin, and ciprofloxacin with a minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of 0.047μg/mL) was isolated from the blood culture; antimicrobials were then changed to ciprofloxacin (intravenous, 400mg b.i.d) and clindamycin (intravenous, 600mg t.i.d). The culture from a blood sample obtained on the second day during the first treatment was negative. The treatment of the patient was completed in 10 days due to the clinical response and because procalcitonin concentration had decreased from 0.7 to 0.2ng/mL. The patient was discharged, but an appointment for a fiberoptic bronchoscopy (FOB) was scheduled, since the patient could not provide a sputum sample for further examination.

Axial chest CT image obtained in patient's first visit to ER (a) shows a cavitary lesion (short arrow) that contains an oval-shaped opacity (arrowhead) in the upper lobe of the right lung. The cavitary lesion is surrounded by a thick wall and parenchymal consolidation (long arrow). Axial CT images of the patient obtained three weeks (b) and five weeks (c) after the first chest CT reveal progressive increase in size of the cavitary lesion (arrows), as well as its content with solid-like appearance (arrowheads). The consolidation around the cavitary lesion also progressed in the right upper lobe. CT findings were suggestive of fungus-ball in a cavity with surrounding consolidation.

When the FOB was done one week after the discharge, the patient was referred to the ER due to mild respiratory distress. Increased respiratory rate (30breaths/min), bilateral coarse crackles, abdominal distention, and bilateral grade 3 pretibial edemas were detected at physical examination. Complete blood count showed an hemoglobin concentration of 8.7g/dL (normal range 13.5–16.9g/dL), a leukocyte count of 15K/μL (normal range 4.3–10.3K/μL) with neutrophils 85.5%, and a platelet count of 179K/μL (normal range 166–308K/μL). Renal and liver function tests, lactate concentration, and arterial pH were reported in the normal range. The procalcitonin concentration was 0.852ng/mL (normal range 0–0.1ng/mL), and the C-reactive protein concentration was 19.23mg/dL (normal range 0-0.5mg/dL). Polymorphonuclear leukocytes and Gram-negative bacillus were reported on the Gram stain of bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid. The acid-fast bacterium stain was negative. Multiplex polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for respiratory infection (Bioeksen R&D Technologies Ltd, Turkey) and SARS-CoV-2 PCR were negative. Follow-up thorax CT revealed a progressed consolidation on the right upper lobe, and increased size of the cavitary lesion with solid-appearing content (Fig. 1b). Having the suspicion of necrotizing pneumonia, meropenem (intravenous, 1g t.i.d) was started.

On day three, the growth of Salmonella, identified by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS) systems (Bruker, Germany), was reported in the BAL fluid culture; the isolate was serotyped in group D by using commercial antisera (Becton Dickinson, USA) and the Kauffmann–White scheme. The Salmonella isolate was subjected to an antimicrobial testing; it was resistant to ciprofloxacin, susceptible to ampicillin, ceftriaxone, and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, according to European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST) guidelines.9 The fungal culture of BAL fluid, which was requested as a part of an opportunistic pathogen investigation, yielded Aspergillus niger (MALDI-TOF MS Score 2.07). Aspergillus galactomannan antigen (Euroimmun Medizinische Labordiagnostika AG, Germany) optical density indices were 10.5 and 0.99 in both BAL fluid and serum.22 Antifungal susceptibility testing was performed and interpreted according to EUCAST guidelines.2,6–8,10 The MIC values were as follows: amphotericin B 0.5μg/mL (susceptible), voriconazole 0.5μg/mL (wild-type), posaconazole 0.25μg/mL (wild-type), and itraconazole 0.25μg/mL (wild-type).2,6–8,10 With a diagnosis of invasive aspergillosis, intravenous voriconazole (6mg/kg twice on day 1, followed by 4mg/kg b.i.d) was added. Blood and urine cultures were negative. Results of transthoracic echocardiogram and renal ultrasonography were reported as non-pathological. The patient was intubated due to respiratory insufficiency. The antimicrobial regimen was de-escalated to ceftriaxone and clindamycin based on the results of susceptibility testing for Salmonella. Voriconazole concentration in serum was 3.7mg/L (normal range 2–6mg/L) on the third day of treatment. All the new cultures from blood, deep tracheal aspirate, urine, as well as Mycobacterium tuberculosis culture and PCR from BAL fluid, were negative. The patient passed away on the 20th day of admission due to disseminated intravascular coagulopathy.

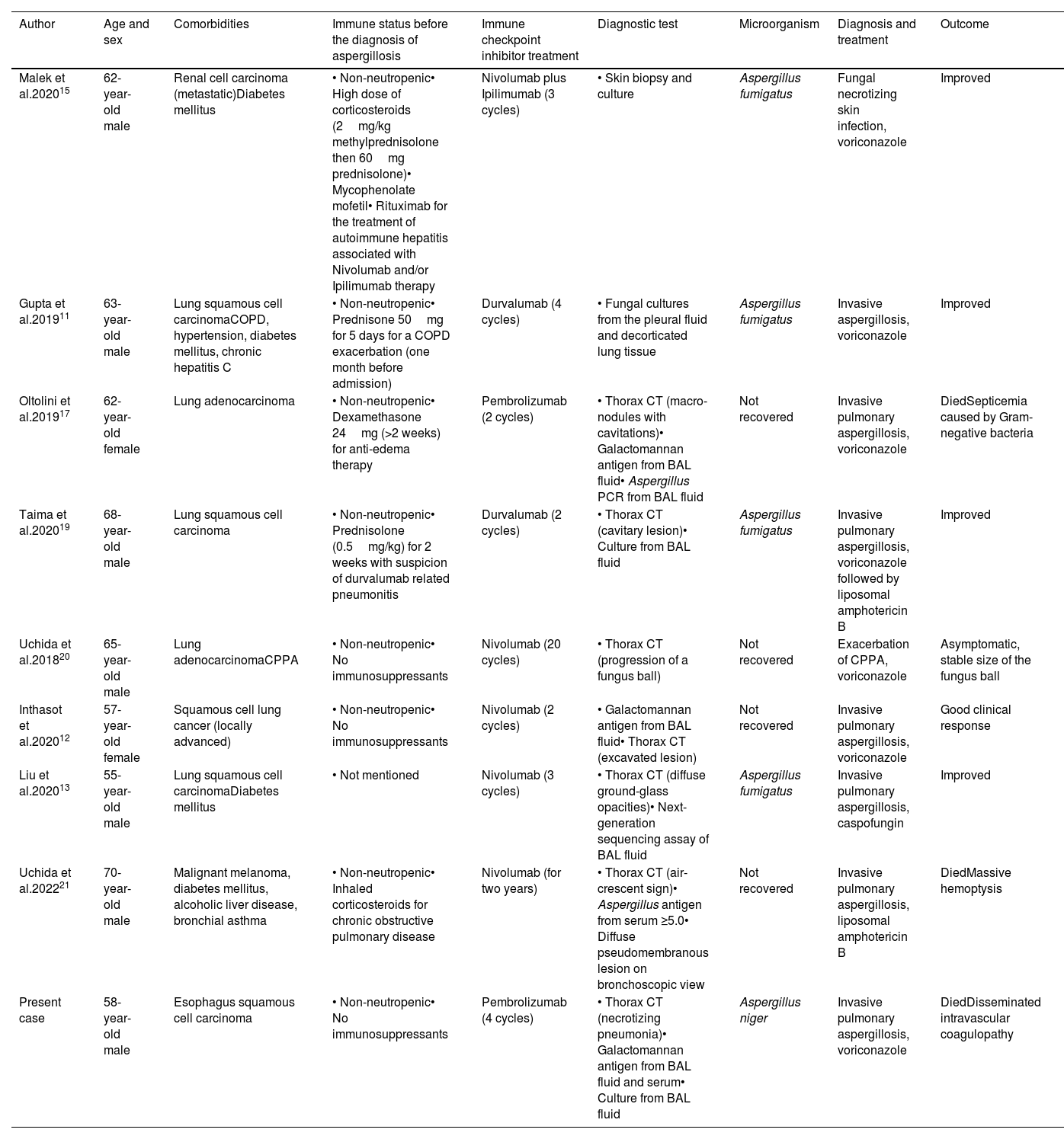

DiscussionThe immune-related adverse events can affect multiple organs, including the lungs, in which potentially life-threatening pneumonitis may require rapid immunosuppressive treatment.12 Opportunistic infections usually occur following immunosuppressant therapy for immune-related adverse events.1,14 We found in the literature eight patients with invasive aspergillosis who were treated with ICIs11–13,15,17,19–21; four of them were receiving systemic corticosteroids, and one inhaled corticosteroids11,15,17,19,21 (Table 1). Our patient did not have a history of prolonged neutropenia or any immunosuppressive therapy before the diagnosis of invasive aspergillosis. Since some cases of this mycosis induced by immunotherapy in the absence of immunosuppression have been reported,12,20,21 hyperinflammatory dysregulated immune response after ICI therapy can be hypothesized as a cause of the pathogenesis in invasive aspergillosis.4,14

Clinical and demographic characteristics of the presented case and previously published cases of invasive aspergillosis after having immune-check point inhibitor treatment.

| Author | Age and sex | Comorbidities | Immune status before the diagnosis of aspergillosis | Immune checkpoint inhibitor treatment | Diagnostic test | Microorganism | Diagnosis and treatment | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Malek et al.202015 | 62-year-old male | Renal cell carcinoma (metastatic)Diabetes mellitus | • Non-neutropenic• High dose of corticosteroids (2mg/kg methylprednisolone then 60mg prednisolone)• Mycophenolate mofetil• Rituximab for the treatment of autoimmune hepatitis associated with Nivolumab and/or Ipilimumab therapy | Nivolumab plus Ipilimumab (3 cycles) | • Skin biopsy and culture | Aspergillus fumigatus | Fungal necrotizing skin infection, voriconazole | Improved |

| Gupta et al.201911 | 63-year-old male | Lung squamous cell carcinomaCOPD, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, chronic hepatitis C | • Non-neutropenic• Prednisone 50mg for 5 days for a COPD exacerbation (one month before admission) | Durvalumab (4 cycles) | • Fungal cultures from the pleural fluid and decorticated lung tissue | Aspergillus fumigatus | Invasive aspergillosis, voriconazole | Improved |

| Oltolini et al.201917 | 62-year-old female | Lung adenocarcinoma | • Non-neutropenic• Dexamethasone 24mg (>2 weeks) for anti-edema therapy | Pembrolizumab (2 cycles) | • Thorax CT (macro-nodules with cavitations)• Galactomannan antigen from BAL fluid• Aspergillus PCR from BAL fluid | Not recovered | Invasive pulmonary aspergillosis, voriconazole | DiedSepticemia caused by Gram-negative bacteria |

| Taima et al.202019 | 68-year-old male | Lung squamous cell carcinoma | • Non-neutropenic• Prednisolone (0.5mg/kg) for 2 weeks with suspicion of durvalumab related pneumonitis | Durvalumab (2 cycles) | • Thorax CT (cavitary lesion)• Culture from BAL fluid | Aspergillus fumigatus | Invasive pulmonary aspergillosis, voriconazole followed by liposomal amphotericin B | Improved |

| Uchida et al.201820 | 65-year-old male | Lung adenocarcinomaCPPA | • Non-neutropenic• No immunosuppressants | Nivolumab (20 cycles) | • Thorax CT (progression of a fungus ball) | Not recovered | Exacerbation of CPPA, voriconazole | Asymptomatic, stable size of the fungus ball |

| Inthasot et al.202012 | 57-year-old female | Squamous cell lung cancer (locally advanced) | • Non-neutropenic• No immunosuppressants | Nivolumab (2 cycles) | • Galactomannan antigen from BAL fluid• Thorax CT (excavated lesion) | Not recovered | Invasive pulmonary aspergillosis, voriconazole | Good clinical response |

| Liu et al.202013 | 55-year-old male | Lung squamous cell carcinomaDiabetes mellitus | • Not mentioned | Nivolumab (3 cycles) | • Thorax CT (diffuse ground-glass opacities)• Next-generation sequencing assay of BAL fluid | Aspergillus fumigatus | Invasive pulmonary aspergillosis, caspofungin | Improved |

| Uchida et al.202221 | 70-year-old male | Malignant melanoma, diabetes mellitus, alcoholic liver disease, bronchial asthma | • Non-neutropenic• Inhaled corticosteroids for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | Nivolumab (for two years) | • Thorax CT (air-crescent sign)• Aspergillus antigen from serum ≥5.0• Diffuse pseudomembranous lesion on bronchoscopic view | Not recovered | Invasive pulmonary aspergillosis, liposomal amphotericin B | DiedMassive hemoptysis |

| Present case | 58-year-old male | Esophagus squamous cell carcinoma | • Non-neutropenic• No immunosuppressants | Pembrolizumab (4 cycles) | • Thorax CT (necrotizing pneumonia)• Galactomannan antigen from BAL fluid and serum• Culture from BAL fluid | Aspergillus niger | Invasive pulmonary aspergillosis, voriconazole | DiedDisseminated intravascular coagulopathy |

COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CPPA: chronic progressive pulmonary aspergillosis; CT: computed tomography; BAL: bronchoalveolar lavage; PCR: polymerase chain reaction; Nivolumab and Pembrolizumab: PD-1 inhibitors; Durvalumab: PD-L1 inhibitors; Ipilimumab: CTLA-4 inhibitors.

For the differential diagnosis, it is important to consider an extensive list of several opportunistic pathogens. Carrying out both bacterial and fungal cultures, as well as Aspergillus galactomannan antigen in BAL fluid, enabled, in our case, the diagnosis of an unusual coinfection. Consecutive Aspergillus and Salmonella infections were reported in two patients, one with sickle cell anemia and the other with chronic granulomatous disease.17,18 In our case, there was neither history of hemoglobinopathy, nor recurrent or necrotizing infections. Pulmonary infections related to non-typhoidal Salmonella may present with lobar pneumonia and be complicated with lung abscess, empyema, and bronchopleural fistula formation.18 A previous study showed that Salmonella enterica ser. Typhimurium can make biofilms on the hyphae of A. niger, while other bacteria cannot.5 Moreover, a mutualistic interaction observed between S. enterica and A. niger might had favored the co-infection.3 Concerning our case, we hypothesize that Salmonella spread to the lung by hematogenous route after the first admission of the patient, as 10 days of ciprofloxacin did not result in a microbiological cure. Then, the biofilm made by Salmonella might have protected A. niger conidia from the immune system, already impaired by ICI therapy with high-dose cytotoxic agents. This interaction might have caused an invasive co-infection. However, this hypothesis is only a speculation which requires to be proven in an animal model.

To the best of our knowledge, we report the first case of invasive Salmonella infection complicated by an invasive aspergillosis in a patient who received ICI treatment. Awareness of unusual pathogens in the etiology of pneumonia after an ICI treatment may help to avoid underdiagnosis.