The present study investigated the use of parent training and parent-delivered narrative language intervention to increase narrative language comprehension and production in children with intellectual disability (ID). Fourteen children with ID and their parents took part in the study. Parents participated in a live workshop to learn the methods for narrative language intervention and were provided with a packet of materials and two preselected books. After the session, they completed the training at home with their children over a period of 8 weeks. Children were pre tested and post tested for narrative language skills. Parents reported to the primary investigator weekly during the study and completed a survey following the conclusion of the intervention. Parents reported positive outcomes in that they gained knowledge of narrative language skills and were able to incorporate the materials provided and techniques learned to increase their child's language comprehension and production.

El presente estudio analizó la utilización de la formación parental y la intervención del lenguaje narrativo realizada por los padres, para incrementar la comprensión y la producción del lenguaje narrativo en niños con discapacidad intelectual (DI). Catorce niños con DI, y sus padres, tomaron parte en el estudio. Los padres participaron en un taller en vivo para aprender los métodos de intervención del lenguaje narrativo, y recibieron un paquete de materiales y dos libros preseleccionados. Tras la sesión, completaron la formación en casa con sus hijos durante un periodo de ocho semanas. A los niños se les realizaron pruebas previas y finales, sobre técnicas del lenguaje narrativo. Durante el estudio, los padres enviaron un reporte semanal al investigador principal, y completaron una encuesta a la conclusión de la intervención. Los padres reportaron resultados positivos en cuanto a mejora del conocimiento sobre técnicas del lenguaje narrativo, y fueron capaces de incorporar los materiales suministrados y las técnicas aprendidas para incrementar la comprensión y la producción de lenguaje por parte de sus hijos.

Narrative skill is the ability to retell a story. Narrative language relates an account of experiences or events that are temporally sequenced and convey some meaning.1 Narrative discourse includes fictional stories, scripts, and accounts that are designed to entertain or inform the audience. The speaker demands are greater in narrative discourse because one person tells the narrative while others listen. Specific skills that contribute to this ability include skills in organization, sequencing a chain of events, understanding and being able to recount information about topic, setting, time, problems and goals of the characters, their internal states, attempts to solve the problems, and resolution of the problems.2 Difficulty in narrative skills is common in individuals with intellectual disabilities.3 Individuals with Down syndrome comprise the largest group of individuals with ID with a genetic etiology. Based on the intellectual disability,3,4,7 speech and language difficulties,4,6,7 hearing difficulties,5 and short-term memory difficulties,6,7 children and adults with Down syndrome do have difficulties with reading and with narratives. Prior to the 1980s, it was considered unlikely or even impossible for children with Down syndrome to read. Currently, many children with Down syndrome learn to read effectively at a 3rd–5th grade level or even higher, and this helps them with learning language concepts, with school performance in childhood, and with employment and independent living in adults.8

There are many reasons why narratives are a good choice to focus on or target in an intervention. Narrative skills are highly associated with literacy and other academic skills.9 In addition, narratives occur naturally within and outside of school settings allowing for generalization of skills that would be learned in a therapeutic setting.10 Narrative production also is related to many levels and aspects of vocabulary, grammar, and conversational skills.11 Finally narratives take into account the diversity of speakers.

What does research tell us regarding the ability to retell narratives in children and adults with intellectual disabilities? Chapman and her colleagues found that adults with Down syndrome were capable of producing complex sentences in their narratives.12–14 Kay-Raining Bird et al.,15 found that when children with Down syndrome and adolescents retold a story, they produced a comparable number of story episodes whether the modality used was oral, hand-written or word processed. Miles and Chapman12 demonstrated that children and adults with Down syndrome were able to use effective narrative language skills when using a wordless story (“Frog, Where are you?”) as a prompt. The results showed that the individuals with Down syndrome were able to identify the plot, story theme, and problems encountered by the characters more often than the group matched for similar level of expressive language skills.

The research on narratives focuses on assessment. There are only two published articles that target intervention. Schoenbrodt et al.,16 in a study of 2 children with Down syndrome, used a parent training program to teach narrative and vocabulary skills. Following a 4 week period of at-home intervention and shared book reading, the children improved on both narrative skills and vocabulary. Lecas et al.,17 in a study of one child with Down syndrome, based his intervention training on the documented superiority of learning through visual memory rather than auditory memory. The client was able to use a software program to illustrate a story as he was hearing it. Results were that the client was able to increase both comprehension and information recall.

Studies have documented that parent training helps improve outcomes for their children with intellectual abilities.16,18,19 Shared book reading has been found to be highly correlated with literacy skills. Trenholm and Mirenda,19 using a parent survey, found that although parents of children with Down syndrome read to their children, they did not usually ask higher level comprehension questions such as what would happen next. Based on his research, Ricci20 believes that the home literacy environment is a predictor of the interest children with Down syndrome have in reading. Parental beliefs about reading, including their propensity to ask questions and the types of questions they ask during shared reading, correlated highly with reading comprehension and receptive vocabulary skills. Schoenbrodt et al.,16 trained parents to read and ask questions to help their children improve their narrative skills. The present study focused on training parents to help their children improve narrative skills.

MethodsParticipants in this study included 14 school-aged children, 9 girls and 5 boys, ranging from 5 to 19 years old with varying degrees of intellectual disability. Participants were all clients of the Loyola Clinical Centers with a diagnosis of Down syndrome. The clients and their families were personally invited to participate in the study. Families were chosen to participate because the parents had indicated that they had noticed their child having difficulty in reading comprehension. Parents were instructed to fill out a questionnaire about their child's native language, speech abilities, reading comprehension, and the reading level of the books that the parent and child usually read together. All of the parents reported reading short story books with illustrations and some also read picture books or chapter books with their child.

Pre-testing took place at the Loyola Clinical Centers in Columbia, MD and was administered by graduate and undergraduate students majoring in Speech-Language-Hearing Sciences from Loyola University Maryland. They were supervised by the Loyola Clinical Centers clinical faculty members. Participants were pre-tested using the Test of Narrative Language,21 Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test 4,22 and wordless picture books for story generation. The storybooks used for the story generation task included “Frog Where Are You?” and “A Boy, A Dog, and A Frog” by Mercer Mayer. The pre-testing was done in a large classroom and set up in stations.

Parents were trained in a separate room by the investigator, a certified speech-language pathologist, on how to incorporate the narrative intervention during shared storybook reading at home. The training session included an overview of the study and a parental permission for participation form, a PowerPoint presentation on narrative language, and a description of narrative language intervention and techniques for intervention. The principle investigator reviewed each portion of the intervention with the parents. For each book, materials and activities were included in a packet given to each parent. Parents were also given a schedule detailing the activities to administer each day as well as a Story Grammar Marker® (SGM)23 to be used during storybook reading. The materials for “Rainbow Fish” consisted of pre-story activities, semantic word map, story grammar chart, episode map, internal states chart, feelings words, comprehension questions, and art projects. For “Strega Nona,” parents were given a strategies checklist, semantic word map, story grammar chart, episode map, internal states chart, feelings words, comprehension questions, and art projects.

The study was divided into two parts. Parents were told to read two books with their child throughout the study, “Strega Nona” by Tomie da Paola and “Rainbow Fish” by Marcus Pfister. For the first 4 weeks of the study, parents were to read one book with their child. Then after the third week, parents were instructed to switch books. They were also given a schedule to help guide them through the intervention. The schedule indicated which intervention to implement on a specific day. The interventions took place four times a week with Wednesday being a break from the intervention. On that day, parents reported to the principle investigator via email details about their child's performance, strengths, weaknesses, and any other valuable information. They were also able to ask questions about the strategies and materials they were using with their children.

The interventions became more complex as the weeks progressed. The first week of the intervention introduced the child to the story. As opposed to reading the story, the parent engaged the child in pre-story activities such as a semantic word map, picture walk discussion, and vocabulary lesson. For the first 2 days of the week, the child was presented with a semantic word map and picture walk discussion. A semantic word map places a word or concept in the middle of the page surrounded by ideas and details of the word. At the top of the page, the child is asked to think of words that relate to a main item in the story. For instance, the word “pasta” can be placed in the middle of the web for the book “Strega Nona.” The child is then asked to think of words that relate to pasta. The words are then placed into categories such as toppings, shapes, and sizes in the web. In addition to the semantic word map, the parent was also instructed to do a picture walk through the book with the child during the first 2 days of the first week of the intervention. A picture walk introduces the child to the story and gives them the opportunity to comment on the pictures. The parents were encouraged to ask the child questions about the pictures such as, “What do you think is happening in this picture?” or “Who do you think the character is?” and incorporate words from the semantic word map into the discussion. In the latter part of the week, parents were instructed to present and teach vocabulary from the story that the child may have difficulty with. This activity helps the child understand and read through the story more easily.

The second week of intervention incorporated the Story Grammar Marker (SGM) while reading the story. The SGM is a visual-kinesthetic tool which helped participants better understand the elements of the story. Story elements include the setting, characters, initiating event or problem, internal response, plan, attempts, consequence, and resolution. The SGM is made from a braided yarn with beads and clips placed along the yarn to represent the different elements of the story. During the beginning of the second week, parents were told to read the story twice while using the SGM. Then on Thursday and Friday, parents were instructed to read the story with the SGM and then complete the internal response chart with the child. The internal response or internal states chart focuses on the characters and feelings present in the story. The chart asks the child to identify a character, describe a scene in the story, identify how the character feels, and describe why the character feels that way. These activities help the child increase his or her ability to identify story elements and feelings, and also understand why certain events or feelings may be occurring.

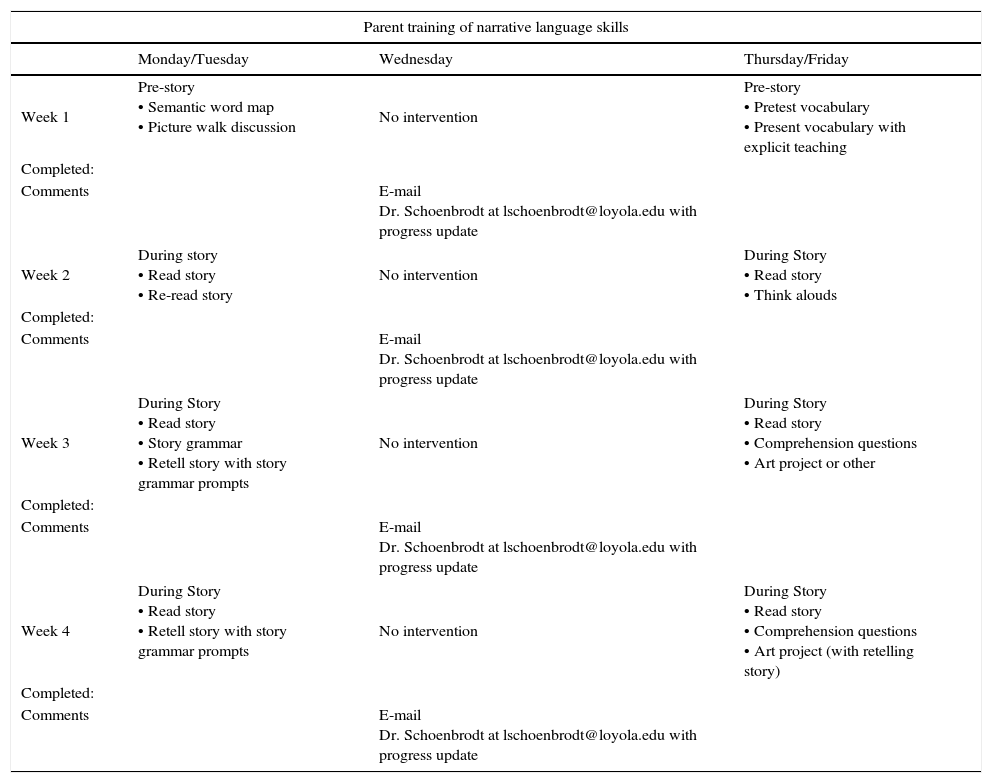

Finally, the third and fourth weeks of the intervention utilized a story grammar map as well as comprehension questions for the story. At this point of the intervention, the child will have hopefully gained an overall understanding of the story after having read the story with his or her parent during the prior 2 weeks. The story grammar map and comprehension questions require the child to apply what they have read and utilize more challenging narrative skills. For instance, the story grammar map asks the child to identify the setting, problem, episodes, and ending of the story. The comprehension questions encourage the child to apply what he or she learned to real-life situations such as “If you were the wise octopus, what would you tell Rainbow Fish to do? Why?” or “What are some things that are hard for you to share?” The parent is encouraged to use story grammar prompts as well as the SGM to help his or her child better understand the concepts of the story. Art projects were also suggested for parents to complete with their child. Suggestions included a craft utilizing uncooked pasta for “Strega Nona” and creating the child's own Rainbow Fish with colored sequins. See Table 1 for a detailed schedule.

Four week intervention schedule provided for parents.

| Parent training of narrative language skills | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Monday/Tuesday | Wednesday | Thursday/Friday | |

| Week 1 | Pre-story • Semantic word map • Picture walk discussion | No intervention | Pre-story • Pretest vocabulary • Present vocabulary with explicit teaching |

| Completed: | |||

| Comments | E-mail Dr. Schoenbrodt at lschoenbrodt@loyola.edu with progress update | ||

| Week 2 | During story • Read story • Re-read story | No intervention | During Story • Read story • Think alouds |

| Completed: | |||

| Comments | E-mail Dr. Schoenbrodt at lschoenbrodt@loyola.edu with progress update | ||

| Week 3 | During Story • Read story • Story grammar • Retell story with story grammar prompts | No intervention | During Story • Read story • Comprehension questions • Art project or other |

| Completed: | |||

| Comments | E-mail Dr. Schoenbrodt at lschoenbrodt@loyola.edu with progress update | ||

| Week 4 | During Story • Read story • Retell story with story grammar prompts | No intervention | During Story • Read story • Comprehension questions • Art project (with retelling story) |

| Completed: | |||

| Comments | E-mail Dr. Schoenbrodt at lschoenbrodt@loyola.edu with progress update | ||

Post-testing followed immediately after the end of the study. All testing materials were the same except the TNL was not used in the post-test and “A Boy, A Dog, and A Frog” was replaced by “Rainbow Fish.” After 16 weeks, a parent survey was conducted and parents provided feedback for the study.

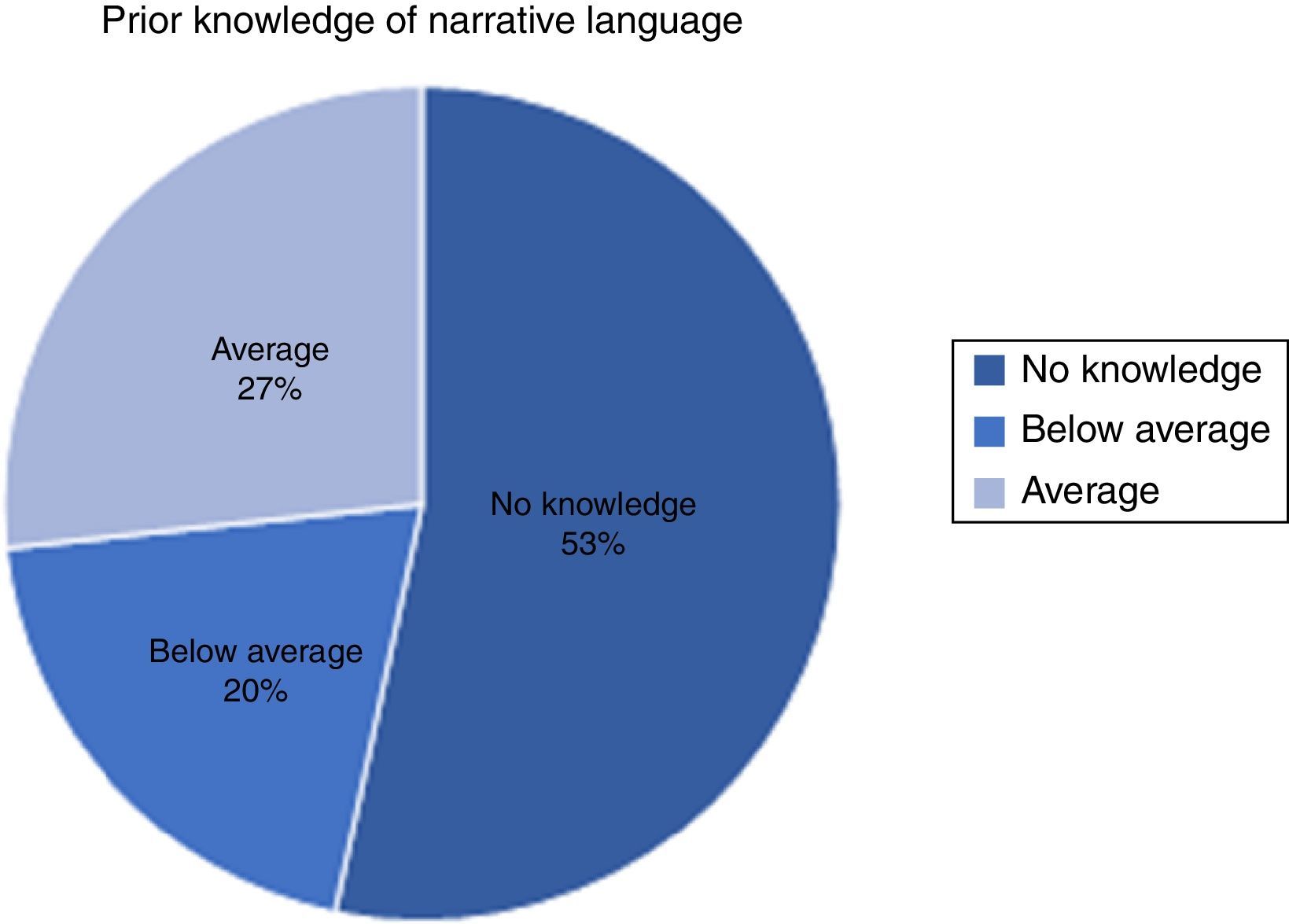

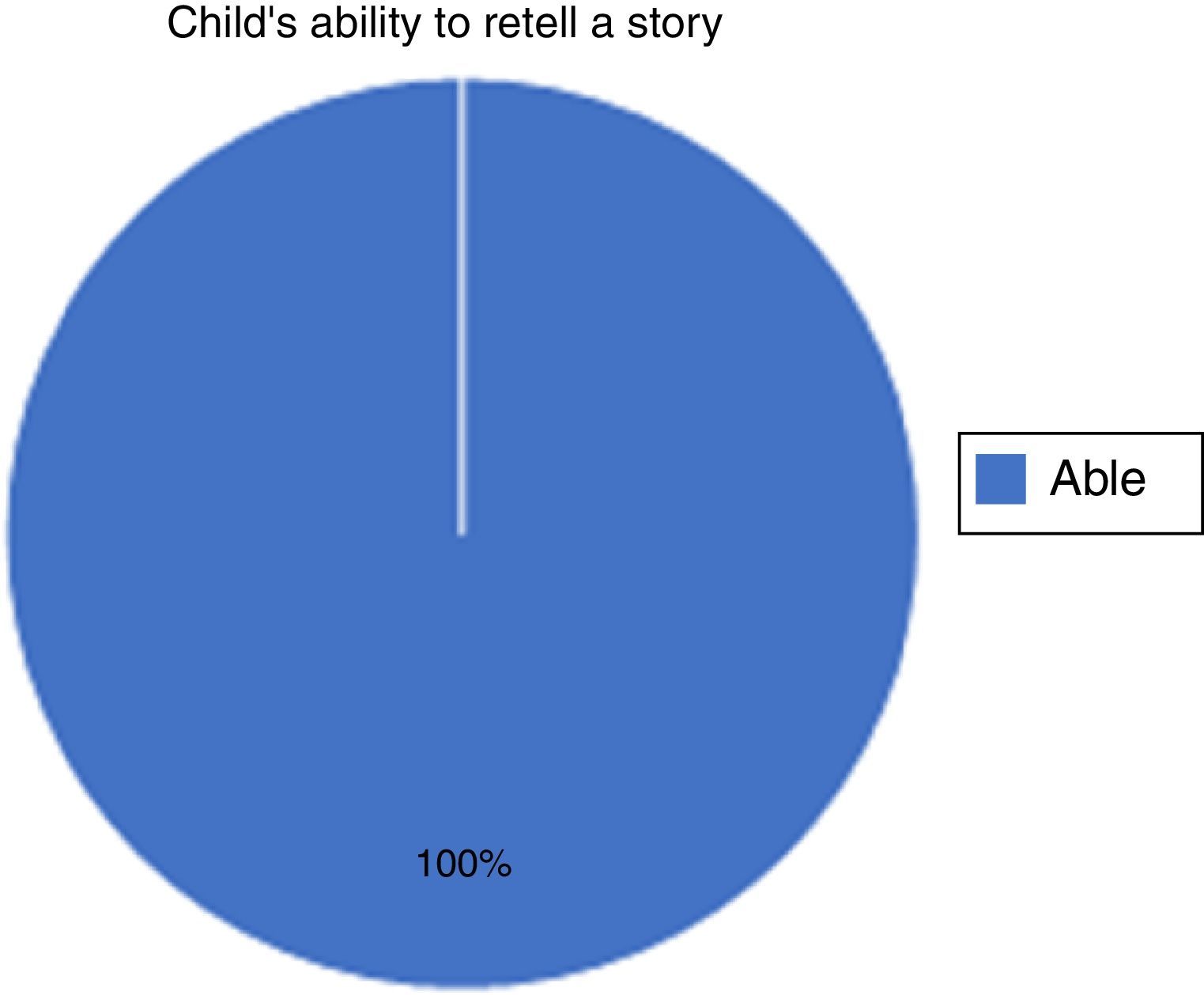

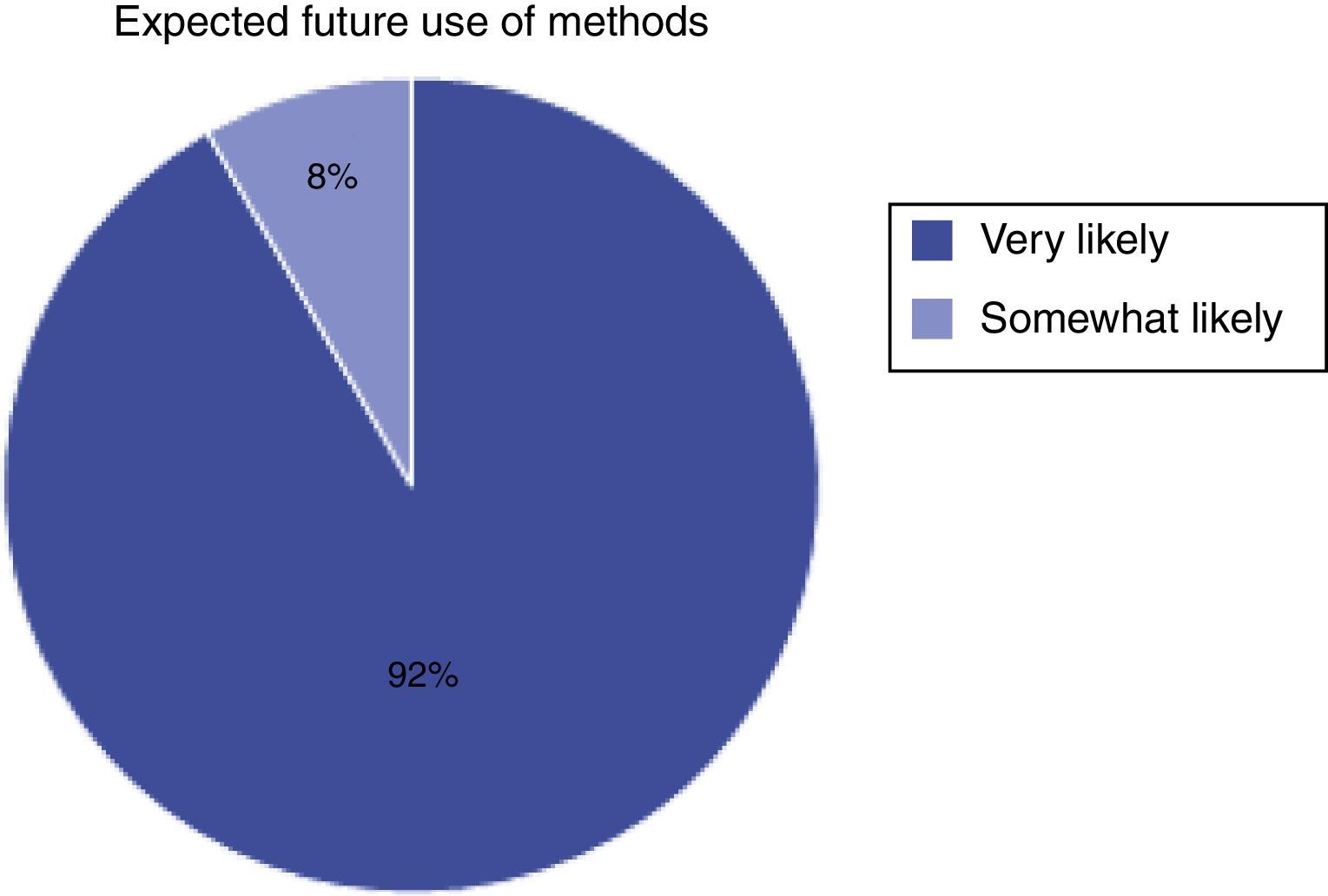

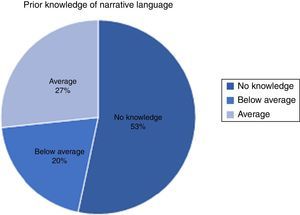

ResultsThis study measured how a parent-delivered narrative language intervention model improved the participants’ (n=14) comprehension of narrative language. Directly after the 6 weeks of narrative language intervention, the parents of the participants were asked to complete a survey. A parent of each participant completed this survey via Qualtrics. The survey inquired about the parents’ prior knowledge of narrative language (Fig. 1). The results gathered from Fig. 1 determined that, prior to the beginning of the study, a majority of parents (73%) had below average to no prior knowledge of narrative language. After an initial training session on parent-delivered narrative language intervention and six weeks of implementation, however, all parents (100%) reported that his/her child was able to retell a story (Fig. 2).

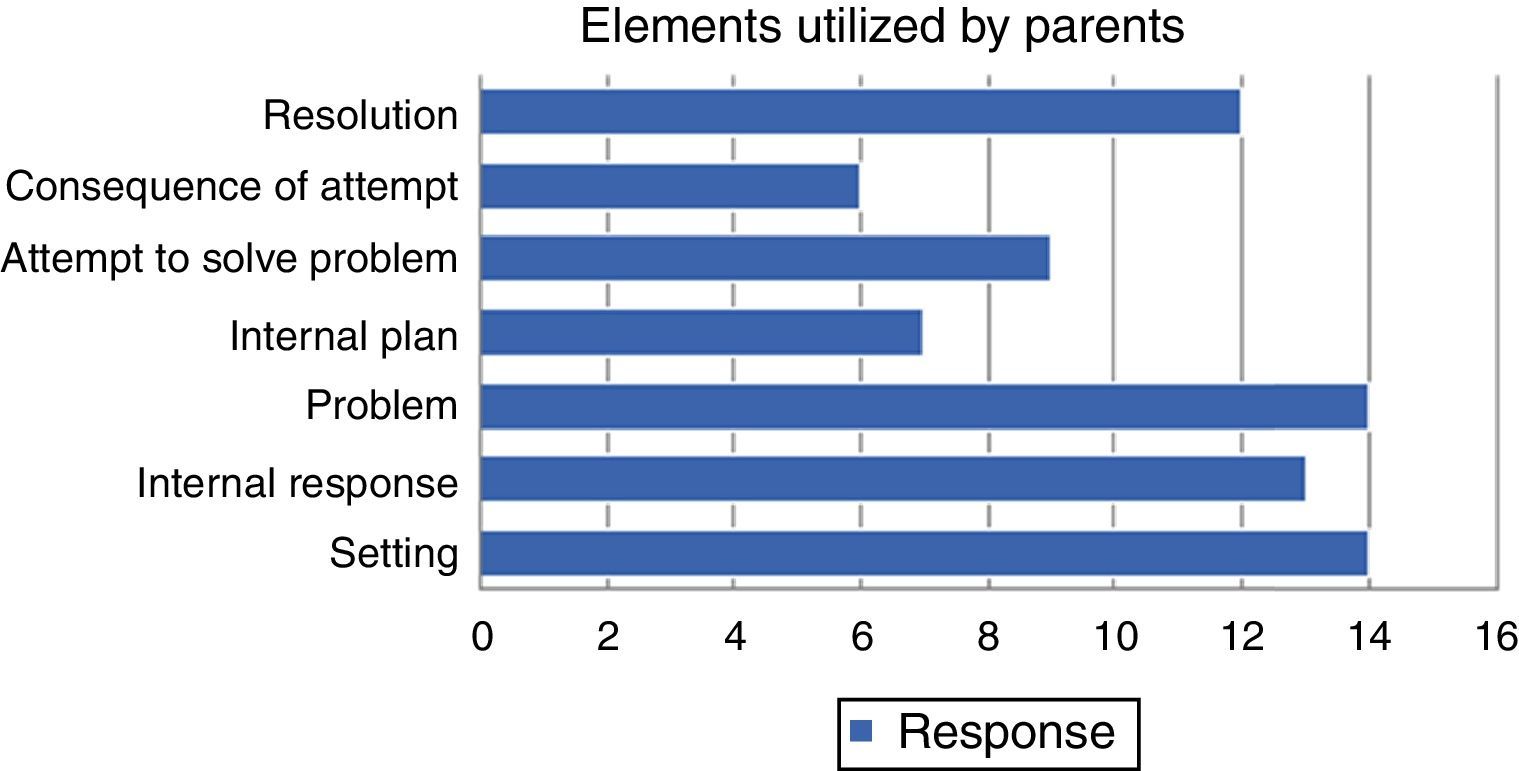

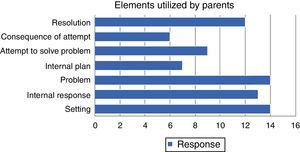

Seven elements of story grammar were provided for the parents to utilize while implementing the narrative language intervention for the books “Strega Nona” and “Rainbow Fish.” These elements included setting, internal response, problem, internal plan, attempt to solve problem, consequence of attempt, and resolution. Fig. 3 represents which elements of story grammar were utilized by parents. All 14 parents utilized the elements of “setting” and “problem” to teach story grammar. The two elements that were used the least by the parents included “consequence of attempt” and “internal plan.” About 43% of parents used “consequence of attempt” and 50% used “internal plan.” Because the study utilized a parent-delivered intervention model, it was important to document the success of the parent training.

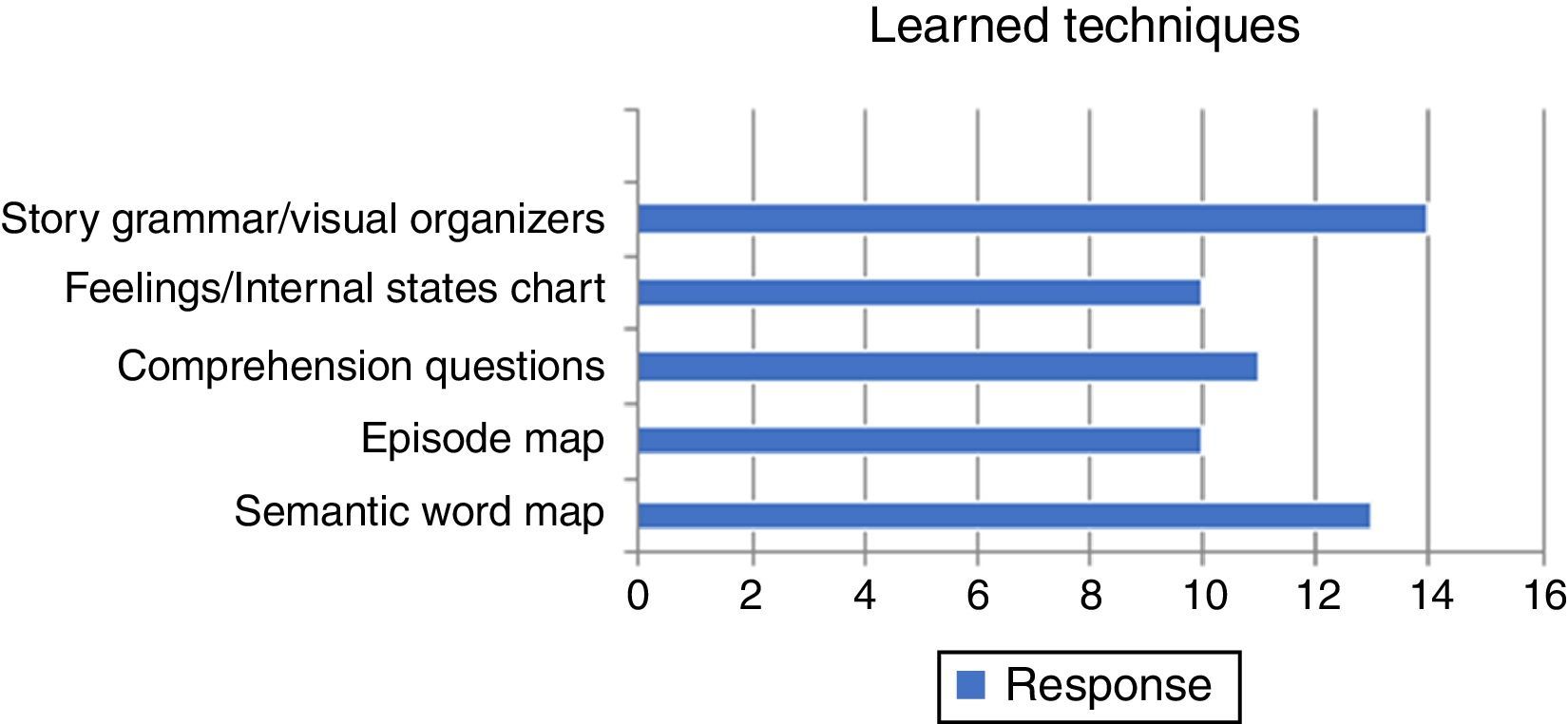

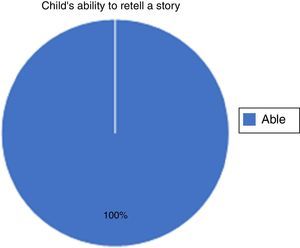

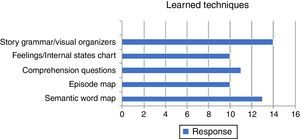

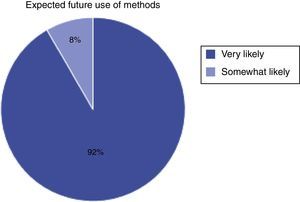

Information about what the parents learned is included in Fig. 4. The learned techniques that the parents reported using to teach narrative language to their child included story grammar/visual organizers, feelings/internal states chart, comprehension questions, episode map, and semantic word map. All 14 parents reported that what they learned about story grammar/visual organizers helped them teach narrative language to their children. About 71% of parents claimed that they did not learn the techniques of “feelings/internal states chart” and “episode map.” When the investigators asked about expected future use of methods, 92% of parents reported that it was very likely that they would use the methods of narrative language intervention in the future and 8% of parents reported that it was somewhat likely that they would use the methods in the future (Fig. 5).

At the end of the 6 weeks of structured intervention using the books “Strega Nona” and “Rainbow Fish,” the investigators conducted post tests at the Loyola Clinical Centers in Columbia, MD. The post-test utilized the books “A Boy, A Dog, and A Frog” and “Strega Nona” to gather results. All other materials used for post-testing were the same as the materials used for pre-testing, except the TNL was not used. The post-tests were conducted by Loyola graduate students in the Speech–Language–Hearing Sciences program and were supervised by the Loyola Clinical Centers clinical faculty members. The participants were unfamiliar with graduate students conducting the post-tests. While the participants underwent post-testing with the graduate students, the investigators conducted interviews with the parents who delivered the intervention. The data obtained from the post-tests and narrative analyses, by the unfamiliar examiners, showed little to no gain and were not included in the results section of this study. The results from the parent surveys, however, documented the areas of success and mastery of the skills.

At the end of the 8 weeks of structured intervention, parents were also encouraged to continue using the methods of intervention with a book of the participant's choice. Sixteen weeks after the completion of the study, the parents of the participants were asked to complete the Follow-Up Narrative Language Parent Survey, which was created by the investigators. Four out of the 14 parents, about 28%, who were involved in the parent-delivered intervention completed the Follow-Up Survey. Three parents emailed the investigators and said that they did not have time to complete the Follow-Up Survey, although they wanted to. The remaining 9 parents did not complete the survey and did not communicate with the investigators about why they did not complete the survey. The Survey asked 8 questions pertaining to the parents’ observations and sentiments about the parent-delivered narrative language intervention. These questions regarded the parents’ feelings toward their level of preparation and competence, the specific strategies utilized throughout the intervention, and the elements the child was able to identify in the story.

The information gathered from the follow-up survey communicated that 100% of the participants (n=4) were able to identify the internal response of the character from the book of their choice. Seventy-five percent of participants were able to identify setting, 50% were able to identify the problem and the resolution, and 25% were able to identify the internal plan, the attempt to solve a problem, and the consequence of an attempt. All parents used comprehension questions to facilitate narrative intervention, 3 parents used story grammar prompts and visual organizers to retell a story, 2 parents used feelings/internal state chart, and 1 parent used a semantic word map. Zero participants developed or used additional materials. When the parents were asked about how competent they felt about continuing with the narrative language intervention on a scale from 1 to 7, 75% of parents reported a 5 (somewhat better) and 25% of parents reported a 6 (better). However, even with feelings of competency, 75% of parents would be interested in receiving additional training or support.

DiscussionThe results of the study hold many implications. The fact that there were negligible gains in actual narrative development noted is a finding in and of itself. Throughout the study, it became clear that the measures that were used in the pretest would not be sensitive enough to show gains at the end of the study. As a result, a measure was added to see if changes would be noted if one of the books used during the training session was integrated into the post-testing. The book “Rainbow Fish” was added in as one of the post-test measures that were administered by a graduate student. Unfortunately, subjects did not show significant improvements in narrative language development skills in this condition. After further analysis, two conclusions can be drawn. First, past studies in narrative language intervention have shown that 8 weeks would be sufficient for training. These studies were conducted with children with only language impairments and not existing concomitantly with intellectual disabilities. For the current study, there was a wide range of abilities in children with intellectual disabilities. To see sustainable changes, the training would need to continue for a longer period of time. Second, the post-testing particularly was conducted with a graduate student who was unfamiliar to the subjects and was not part of the training. It would have been interesting to see if there was a different outcome had the parent-child dyad who participated in the actual training been observed using one of the books from the study. Further, observations of the parent-child dyad from pre to post-test would have allowed for direct observation of skills that were learned in the parents and the children.

The greatest gains that were seen in the study evolved from the parent survey and the descriptive information obtained from weekly sessions. First, parents had very little to no knowledge of narrative language development and intervention prior to the study, which increased for all parents at the conclusion of the study. Specifically, they reported they understood and facilitated the teaching of the majority of story grammar elements with the highest response for setting, problem, internal response, attempts to solve a problem, and resolution. Parents also reported that they understood how to use and facilitated the use of visual organizers, internal states charts, comprehension questions, episode and semantic word maps. These were all techniques presented to parents in the training and reinforced as needed during the course of the study. Overall parents indicated that they learned a new tool to help increase language and literacy skills in their children. In addition, parents reported that all children were able to retell stories that were used in the training.

As for the actual training, parents reported that the amount of time overall was sufficient, although one third did ask for additional time to complete the training and this accommodation was allowed. Over 93% of parents found that the study guidelines and materials were user friendly, although some children required modifications in order to allow for maximum learning. For example, one parent reported that her daughter required a speech device to help answer the questions. Others reported that they needed a different book that had fewer words and was better suited for age and ability level. These modifications were made in order to provide the best type of training experience. Another book, “The Quiet Cricket” by Eric Carle was provided along with materials that were developed specifically to that book but within the same parameters as the other materials and books used for training.

Parents were also queried about the feedback they received from their children during the study. The majority reported that their children showed a greater interest in reading the books and asking more questions about the stories. One parents reported, “She enjoyed reading the books and actually learned a lot from each one. She shared a bit more thanks to Rainbow Fish and “listen and follow directions” was more meaningful thanks to Strega Nona.” Another parent reported, “he asked to read Rainbow Fish all the time!” Parents were also asked about the biggest surprise or “aha” moment. One parent reported, “My biggest surprise was that she seemed to enjoy the story MORE as we repeated it.” Several others reported on the fact that the intervention was something as parents, they really can and should be doing. Others were surprised by the fact that their children were able to answer questions about the story days after reading it. One parent reported, “This study really was for parents. I also realized that if I do this consistently, my child will have better reading comprehension and possibly vocabulary”.

Finally, parents were asked about the biggest strength of the study. One parent reported, “the biggest strength was giving us very specific tools that can be transferred to other books. Both the specific activities and the order in which to use them, the framework, are very useful. The tools you gave us are so much richer and better structured and focus on expressive language a lot more, so I find them to be exactly what we need and very helpful”. Another parent responded, “I think this study was awesome. I think it should be considered in the public school setting to help children begin this program at an early age. This could really change our problems with literacy.” All parents were asked about the likelihood of continuing using this strategy and 92% reported very likely, and 8% somewhat likely. In order to evaluate whether parents continued use of the strategies, a follow-up survey was given at 16 weeks after the completion of the study. Parents were alerted that a survey would be given and many reminders were given for completion. Only one fourth of the parents responded to the survey. Of those that responded, many reported that they did not have the opportunity during the summer months to continue with the intervention but hoped to continue once the school year began.

The results of this study indicate that parent training has effective outcomes but needs to be delivered in a way whereby parents can revisit the material that is taught. For example, it would be helpful to have more than one training session for parents who need further explanation. In the present study, parents who needed further training were consulted with individually by phone. Since there was a weekly mandatory check-in, the investigator was able to troubleshoot problems and help parents who needed more information. An additional strategy would be to record training sessions and post them so that parents would be able to review training sessions as often as needed in order to master the skills. A challenge in this study was in developing a set of standard materials that would enable success for various levels of interest and cognitive level. In the current study, the investigator was able to make modifications while remaining within the parameters of the study. In training parents, however, it is critical that they are able to learn to modify strategies and materials so that these work best for their child. In a debriefing interview, many parents felt that they would be challenged in knowing the best types of books to select to continue. The investigators provided them with many resources and ideas, and remained available for further consultation after the study. The study was conducted purposely so that it was completed around the time that school ended with the hope that parents would have a strategy that they could continue in the summer. Future studies may consider the timing and overlap with the conclusion of the school year and summer vacation to help parents be able to structure time to complete and continue the intervention.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.