Current classification of bipolar disorder (BD) in type I or type II, however useful, may be insufficient to provide relevant clinical information in some patients. As a result, complementary classifications are being proposed, like the predominant polarity (PP) based, which is defined as a clear tendency in the patient to present relapses in the manic or depressive poles.

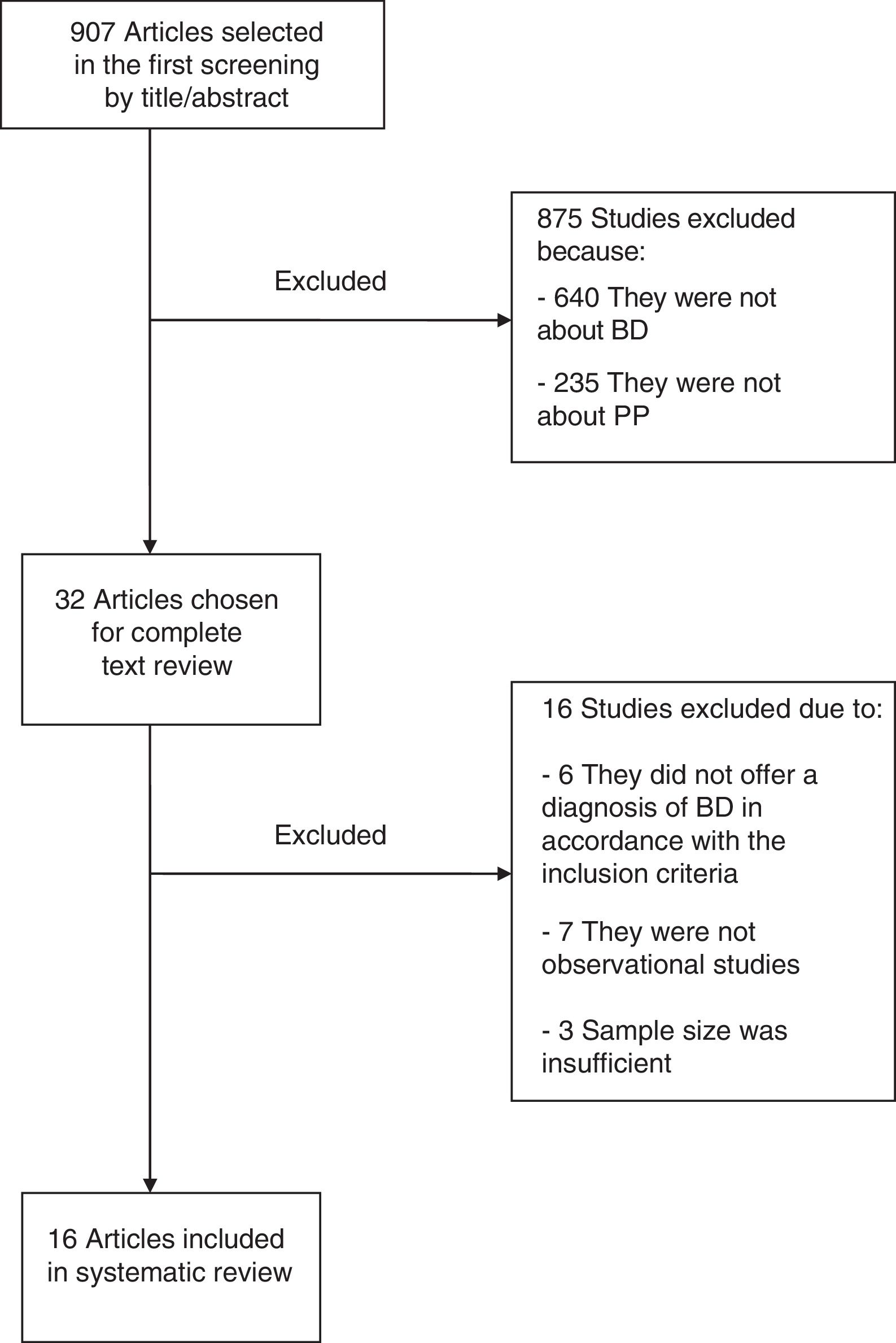

MethodsWe carried out a search in PubMed and Web of Science databases, following the Preferred Items for Reporting of Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses – PRISMA – guidelines, to identify studies about BD reporting PP. The search is updated to June 2016.

ResultsInitial search revealed 907 articles, of which 16 met inclusion criteria. Manic PP was found to be associated with manic onset, drug consumption prior to onset and a better response to atypical antipsychotics and mood stabilisers. Depressive PP showed an association with depressive onset, more relapses, prolonged acute episodes, a greater suicide risk and a later diagnosis of BD. Depressive PP was also associated with anxiety disorders, mixed symptoms, melancholic symptoms and a wider use of quetiapine and lamotrigine.

LimitationsFew prospective studies. Variability in some results.

ConclusionPP may be useful as a supplement to current BD classifications. We have found consistent data on a great number of studies, but there is also contradictory information regarding PP. Further studies are needed, ideally of a prospective design and with a unified methodology.

Las actuales clasificaciones del trastorno bipolar (TB) en tipo I y tipo II, aunque han demostrado utilidad, aportan una información clínica insuficiente en algunos pacientes. Por ese motivo se han propuesto clasificaciones complementarias como la basada en la polaridad predominante (PP) que es definida como la tendencia clara a que el paciente presente recaídas de polaridad maniaca o depresiva.

MétodosRevisión en los buscadores PubMed y Web of Science según las recomendaciones de la Preferred Items for Reporting of Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses-PRISMA-de todos los artículos sobre el TB en los que se analizara la PP, actualizada a junio de 2016.

ResultadosLa búsqueda inicial mostró 907 artículos, de los cuales 16 cumplieron criterios de inclusión. La PP maníaca se asoció a las formas de inicio maníacas, al consumo de tóxicos anterior al TB y a una mejor respuesta a antipsicóticos atípicos y a eutimizantes. La PP depresiva se relacionó con comienzos depresivos, más recaídas, episodios agudos prolongados, mayor riesgo suicida y con un mayor retraso hasta el diagnóstico de TB. También con los trastornos de ansiedad, los síntomas mixtos y melancólicos y el uso de lamotrigina y quetiapina.

LimitacionesVariabilidad en los resultados. Pocos estudios prospectivos.

ConclusiónLa PP puede resultar de utilidad como complemento a las actuales clasificaciones del TB. Se dispone de datos consistentes en numerosos estudios, pero existen otros contradictorios. Se necesitan más estudios prospectivos y con una metodología unificada.

Bipolar disorder (BD) is a chronic mood disease which affects 2.4% of the population worldwide.1,2 The standard course of the disease is depressive episodes alternating with other (hypo) manic and mixed states.3

According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM)-5, BD is divided into BD type i (BDI), which is characterised by the presence of maniac episodes throughout the course of the disease and BD type II (BDII), the diagnosis of which requires at least one depressive and another hypomanic episode.4 For its part, the tenth review of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10)5 distinguishes a first large group generically called “bipolar disorder”, in which the nature of the current episode (manic, hypomanic or depressive) determines its classification and a second group called “other bipolar disorders” which includes BDII. Although these classifications provide useful information, additional encoders have been proposed, which support the clinical symptoms in addressing this complex disease.

Classification based on predominant polarity (PP) were formulated by Angst in 1978, after having conducted a 16 year old follow-up of a sample of 95 bipolar patients.6 He observed that although several patients had not demonstrated a clear tendency and relapsed in both manic and depressive episodes (which he called “nuclear” type), others typically decompensated towards the depressive pole (“predominantly depressive”) and the remainder towards the manic pole (“predominantly manic”). Belonging to one group or another had major repercussions on practice, as each one presented with different sociodemographic, clinical, prognostic characteristics or response to treatments.

Nowadays there is renewed interest in this type of encoding,7–9 and it has been estimated that up to 50% of patients may be classed according to the PP.7,10 however, at present there are no common criteria used by psychiatrists for this, the most highly used being those proposed by Colom et al. (Barcelona proposal).11 According to these authors, if at least two thirds of relapses were depressive, then polarity would be predominantly depressive (PDP), whilst if two thirds of relapses were manic, then polarity would be predominantly manic (PMP).

The lack of common criteria for use may explain the existence of contradictory data in the literature, so that PP was not included as a complimentary encoder in current manuals of classification of psychiatric diseases despite its potential usefulness in clinical practice, as has been shown in multiple studies.

For this reason, we conducted a bibliographic search in the main data bases to identify variables of interest in BD which are related to PP. We think this information will provide relevant data for the research and challenge of this complicated disease.

MethodsFor this study we followed the international recommendations of the preferred items for Reporting of Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses – PRISMA–.12 The data bases used were the Web of Science and Pub Med, with a deadline date of inclusion for articles of 1st June 2016.

The search parameters in PubMed were (“bipolar disorder”[MeSHTerms] OR («bipolar»[AllFields] AND «disorder»[AllFields]) OR «bipolar disorder»[AllFields] OR («bipolar»[AllFields] AND «disorders»[AllFields]) OR «bipolardisorders»[AllFields]) AND «polarity»[AllFields] OR (predominant[AllFields] AND polarity[AllFields]), whilst in the Web of Science they were bipolar disorder AND polarity OR predominant polarity.

Inclusion criteri a were established as articles in English or Spanish on patients diagnosed with BD according to the International Classification of Diseases, 10th review, or the DSM (DSM-III-R to DSM-5) where PP was analysed. In them, the definition of which polarity is used should be clear and 70 was the minimum number of participants established (on considering this figure to be appropriate to detect significant differences among the groups after reading previous related studies).13 Experimental type articles were excluded, those which did not treat l BD or PP, and studies which presented a lower sample size than that indicated. The main researcher (JGJ) was in charge of initial screening, through the reading of titles and abstracts.

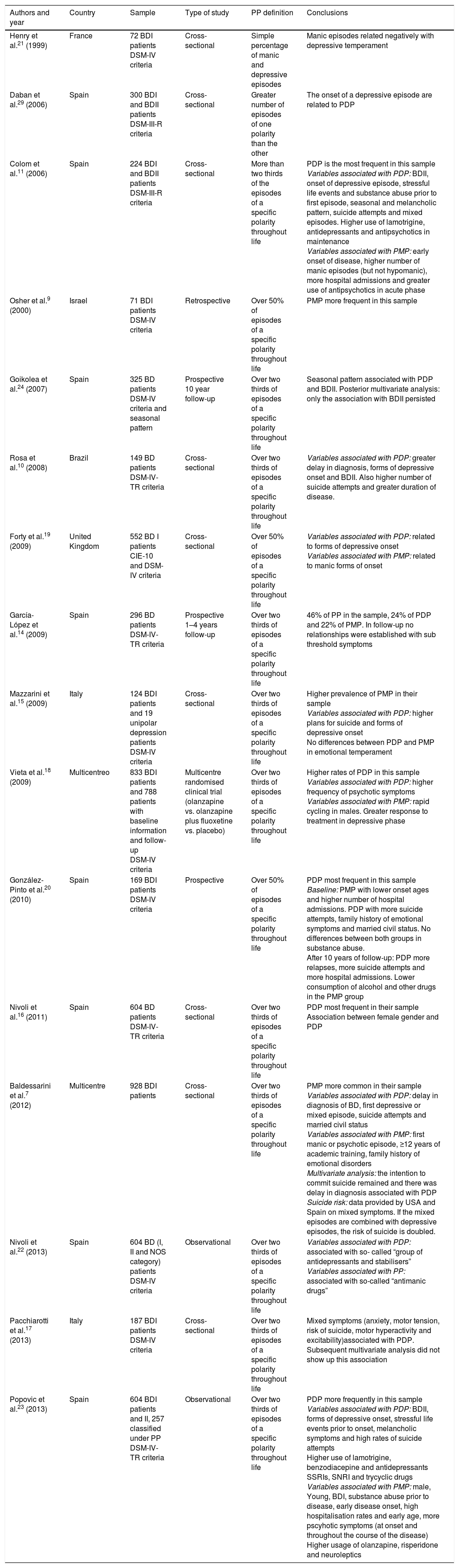

ResultsInitial search showed up 907 studies, of which 875 were excluded for not treating BD or PP. Out of the remaining 32, only 16 met with inclusion criteria (Fig. 1). The variables of interest analysed were: (a) definition of predominant polarity; (b) rates of prevalence; (c) associated socio-demographic variables; (d) clinical variables and (e) implications in clinical management. Results are summarised in Table 1.

Summary of the main characteristics of the articles on predominant polarity in bipolar disorder included in the review.

| Authors and year | Country | Sample | Type of study | PP definition | Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Henry et al.21 (1999) | France | 72 BDI patients DSM-IV criteria | Cross-sectional | Simple percentage of manic and depressive episodes | Manic episodes related negatively with depressive temperament |

| Daban et al.29 (2006) | Spain | 300 BDI and BDII patients DSM-III-R criteria | Cross-sectional | Greater number of episodes of one polarity than the other | The onset of a depressive episode are related to PDP |

| Colom et al.11 (2006) | Spain | 224 BDI and BDII patients DSM-III-R criteria | Cross-sectional | More than two thirds of the episodes of a specific polarity throughout life | PDP is the most frequent in this sample Variables associated with PDP: BDII, onset of depressive episode, stressful life events and substance abuse prior to first episode, seasonal and melancholic pattern, suicide attempts and mixed episodes. Higher use of lamotrigine, antidepressants and antipsychotics in maintenance Variables associated with PMP: early onset of disease, higher number of manic episodes (but not hypomanic), more hospital admissions and greater use of antipsychotics in acute phase |

| Osher et al.9 (2000) | Israel | 71 BDI patients DSM-IV criteria | Retrospective | Over 50% of episodes of a specific polarity throughout life | PMP more frequent in this sample |

| Goikolea et al.24 (2007) | Spain | 325 BD patients DSM-IV criteria and seasonal pattern | Prospective 10 year follow-up | Over two thirds of episodes of a specific polarity throughout life | Seasonal pattern associated with PDP and BDII. Posterior multivariate analysis: only the association with BDII persisted |

| Rosa et al.10 (2008) | Brazil | 149 BD patients DSM-IV-TR criteria | Cross-sectional | Over two thirds of episodes of a specific polarity throughout life | Variables associated with PDP: greater delay in diagnosis, forms of depressive onset and BDII. Also higher number of suicide attempts and greater duration of disease. |

| Forty et al.19 (2009) | United Kingdom | 552 BD I patients CIE-10 and DSM-IV criteria | Cross-sectional | Over 50% of episodes of a specific polarity throughout life | Variables associated with PDP: related to forms of depressive onset Variables associated with PMP: related to manic forms of onset |

| García-López et al.14 (2009) | Spain | 296 BD patients DSM-IV-TR criteria | Prospective 1–4 years follow-up | Over two thirds of episodes of a specific polarity throughout life | 46% of PP in the sample, 24% of PDP and 22% of PMP. In follow-up no relationships were established with sub threshold symptoms |

| Mazzarini et al.15 (2009) | Italy | 124 BDI patients and 19 unipolar depression patients DSM-IV criteria | Cross-sectional | Over two thirds of episodes of a specific polarity throughout life | Higher prevalence of PMP in their sample Variables associated with PDP: higher plans for suicide and forms of depressive onset No differences between PDP and PMP in emotional temperament |

| Vieta et al.18 (2009) | Multicentreo | 833 BDI patients and 788 patients with baseline information and follow-up DSM-IV criteria | Multicentre randomised clinical trial (olanzapine vs. olanzapine plus fluoxetine vs. placebo) | Over two thirds of episodes of a specific polarity throughout life | Higher rates of PDP in this sample Variables associated with PDP: higher frequency of psychotic symptoms Variables associated with PMP: rapid cycling in males. Greater response to treatment in depressive phase |

| González-Pinto et al.20 (2010) | Spain | 169 BDI patients DSM-IV criteria | Prospective | Over 50% of episodes of a specific polarity throughout life | PDP most frequent in this sample Baseline: PMP with lower onset ages and higher number of hospital admissions. PDP with more suicide attempts, family history of emotional symptoms and married civil status. No differences between both groups in substance abuse. After 10 years of follow-up: PDP more relapses, more suicide attempts and more hospital admissions. Lower consumption of alcohol and other drugs in the PMP group |

| Nivoli et al.16 (2011) | Spain | 604 BD patients DSM-IV-TR criteria | Cross-sectional | Over two thirds of episodes of a specific polarity throughout life | PDP most frequent in their sample Association between female gender and PDP |

| Baldessarini et al.7 (2012) | Multicentre | 928 BDI patients | Cross-sectional | Over two thirds of episodes of a specific polarity throughout life | PMP more common in their sample Variables associated with PDP: delay in diagnosis of BD, first depressive or mixed episode, suicide attempts and married civil status Variables associated with PMP: first manic or psychotic episode, ≥12 years of academic training, family history of emotional disorders Multivariate analysis: the intention to commit suicide remained and there was delay in diagnosis associated with PDP Suicide risk: data provided by USA and Spain on mixed symptoms. If the mixed episodes are combined with depressive episodes, the risk of suicide is doubled. |

| Nivoli et al.22 (2013) | Spain | 604 BD (I, II and NOS category) patients DSM-IV criteria | Observational | Over two thirds of episodes of a specific polarity throughout life | Variables associated with PDP: associated with so- called “group of antidepressants and stabilisers” Variables associated with PP: associated with so-called “antimanic drugs” |

| Pacchiarotti et al.17 (2013) | Italy | 187 BDI patients DSM-IV criteria | Cross-sectional | Over two thirds of episodes of a specific polarity throughout life | Mixed symptoms (anxiety, motor tension, risk of suicide, motor hyperactivity and excitability)associated with PDP. Subsequent multivariate analysis did not show up this association |

| Popovic et al.23 (2013) | Spain | 604 BDI patients and II, 257 classified under PP DSM-IV-TR criteria | Observational | Over two thirds of episodes of a specific polarity throughout life | PDP more frequently in this sample Variables associated with PDP: BDII, forms of depressive onset, stressful life events prior to onset, melancholic symptoms and high rates of suicide attempts Higher use of lamotrigine, benzodiacepine and antidepressants SSRIs, SNRI and trycyclic drugs Variables associated with PMP: male, Young, BDI, substance abuse prior to disease, early disease onset, high hospitalisation rates and early age, more pscyhotic symptoms (at onset and throughout the course of the disease) Higher usage of olanzapine, risperidone and neuroleptics |

SNRI: selective noadrenalin reuptake inhibitors; SSRIs: selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors; NOS: bipolar disorder not otherwise specified; PP: predominant polarity; PDP: predominant depressive polarity; PMP: predominant manic polarity; BD: bipolar disorder.

In 11 of the 16 selected articles, the definition of the PP used was the Barcelona proposal, based on the two thirds criteria.11 This criteria establishes an arbitrary cut-off point from which a person presented a PMP when two thirds of their relapses were manic or PDP if they were depressive. Posterior authors followed this definition.10,14–18

Three studies simplified the cut-off point displacing it up to 50%,9,19,20 whilst the remaining 2 established the PP in accordance with the most frequent recurrence in absolute terms.21,22

All these criteria were compared in a multicentre study which concluded that less restrictive definitions would allow more patients to be coded according to PP, but without this being associated with significant differences between the groups.7

PrevalenceIn the reviewed studies, the prevalence of patients for whom a polarity could be identified ranged between 42.4% and 71.8% (median of 52.7%). For PMP this value was 12.4%–55.0% (median of 26%) and in the case of PDP it was 17.0%–34.1% (median of 21.4%). Studies with large samples14,23,24 and with more patients diagnosed with BDII10,11,24,25 presented higher rates of PDP, whilst the PMP was mostly associated with the BDI.7,9,15,17

Socio-demographic variablesArticles which did not analyse the PP indicate that mania is more common in men26,27 and depression in women,28,29 but when polarity is studied this statement does not appear to be as clear. If PPM is associated with the male24 and PDP with the female7,16 in some articles, there are authors who did not find any gender differences.7,9,11,15,18,20

Disparity also exist with regards to a family history of BD, since one study showed a higher family load in PDP22 and the other in PMP,7 whilst in a different article no relevant differences were found.15

For its part, the association between a high academic level and PMP appears clearer, and also that patients with PDP are usually married or live more frequently with their partners.7

Clinical variablesAge at onset and polarity of the first episodePopulation studies indicate that the mean age of starting with BD is between 17 and 27 years,30 whilst diagnosis of a first manic episode usually occurs earlier, between 15 and 18 years of age.22 Compared with other emotional disorders, the start of BD is early,31 often in the form of a depressive episode (up to 67% at onset).22,32

As occurred with gender, this reality appears more complex when polarity is considered, since although several studies showed that onset of PMP came before that of PDP (24.77 vs. 30.69 years),20,22 other articles show early onset of PDP (24±1.97 vs. 29±11 years),10 and similarly there are authors who did not find any significant differences between both polarities (mean age of onset as 22 years).7,11

However, there is consensus regarding the type of symptoms of the first episode and posterior PP, since the beginning of manic episodes are associated long term with PMP7,19,24 and the start of depressive and mixed symptoms will more probably develop into a PDP in the future.7,10,19,24

Number of relapses and duration of the acute episodeThe imbalances in BD are a key prognostic factor, as they lead to progressive impairment in the functional areas of the patient, increasing treatment resistence.24 In BD depressive relapses are usually briefer than unipolar depression, particularly for PMP,15 in which mean duration of an episode is of 2.5 months compared with 2.86 months of PDP and 5.7 months of unipolar depression.15 Furthermore, the majority of studies have shown that in PDP, both the number of relapses (of any type) and their duration is higher than in manic polarity.7,10,20,22 However, not all studies coincide, as several have shown an annual mean recurrence rate which is similar for both PP.7

Relationship with suicide and substance abuseBD entails great suffering for the person, with suicide rates of up to 10%–15% in long-term follow-up.10 Figures governing suicide attempts and suicides are higher in PDP.7,11,20,24 with figures doubling if patients with mixed symptoms are taken into account.7,11

Many publications have shown that substance abuse in BD is up to 27% more common than in the general popluation,33 with alcohol and cannabis being the substances most highly consumed, followed by cocaine and opioids.34 Alcohol abuse is most associated with depressive symptoms both at initial stages and in subsequent relapses,35 whilst cannabis is related to manic imbalances and more severe acute episodes.11,36

In our review the articles which used a more restrictive definition of polarity showed that substance abuse is higher in PMP,7,10 but PDP had more lax definitions and presented with higher rates.7 Moreover, substance abuse appears to precede the onset of BD more frequently in PMP than in PDP.11,22,24

ComorbidityThe prevalence of comorbidity in BD with other psychiatric disorders is very high, particularly in disorders of anxiety, personality and substance abuse. Regarding polarity, PDP has higher rates of co morbidity18,22 (especially with anxiety disorders),10 although one of the selected articles did not find any significant differences between both polarities.7

Regarding organic disorders, CNS injuries, aids and head injuries have been typically associated with BD. Only in one of the studies selected was this issue analysed, but without provision of any conclusive data.11

Other clinical variables clinics analysedIn BD diagnosis is often delayed between 4 and 10 years since the onset of symptoms. This is much more apparent in PDP, since in these patients the first manic episode may take place after several prior depressive relapses.7,10 Also, patients with depressive polarity are usually more oftener diagnosed with BDII8,10,11,24,25 and present on more occasions with melancholic symptoms (psychomotor delay and catatonia).11,24

Most of the selected stuides,8,20,24 but not all,15 showed that the frequency of hospital admissions is greater in patients with manic polarity and this is associated with a worse long-term prognosis. In PMP psychotic symptoms are also more frequent in the first episode7,24 and in the disease evolution,22 with their presence being associated more with more serious and prolonged relapses to higher hospitalisation rates. In contrast, other authors found there was a higher prevalence of psychotic symptoms in PDP.16,18

One study linked PMP with rapid cycling (defined as 4 episodes or more in the same year)18 and in another a seasonal pattern was found in patients with depressive polarity,11 although the latter could not be later replicated.24

At present the role of the so-called emotional temperaments is being analysed, i.e. those lower forms mood variation, relatively stable throughout life, which according to some authors correspond with sub-syndromic manifestations of major emotional disorders.37 Five types have been described (hyperthymic, ciclothymic, depressive, irritable and anxious temperament), the combined prevalence of which has been described in population studies as 20%.37 There is also a strong biological correlation related to changes in serotonin and dopamine,37 and whilst the depressive temperament is observed more in the PDP, the hyperthymic temperament is typical of manic polarity.37 However, a recent publication also related PMP with the cyclothymic temperament.38

To finalise this section we will briefly summarise 2 important issues in BD, which are the level of functionality and cognitive impairment. Recent studies have reported serious limitations in these patients in both social skills and in satisfactory interpersonal relationships.39 These difficulties are associated with both a worse awareness of the disease, more prolonged depressive episodes, poorer general physical health40 and higher rates of unemployment.41 Although the majority of the articles did not find any significant differences with regard to the functionality of the 2 types of polarity,10,20,22 one study showed a major dysfunction of the social type in PDP,11 in keeping with other authors for whom depressive polarity implies worse autonomy, probably from a multifactorial origin where the worst response to treatments conditions a higher number of relapses. 18

Similar to functionality, there is a growing interest in cognitive impairment observed in patients with BD, since it appears that these changes occur both in relapses and in phases of euthymia, and although they may be of lower intensity tan that of schizophrenia, functions deteriorate such as the ability to pay attention or the working memory, among others.42 It seems clear that impairment worsens with successive relapses,43 but no specific studies in PP are available.

Treatment implicationsResponse to treatment for BD is multifactorial, and is impacted by variables such as previous relapses of the patient, their level of therapeutic adherence, associated co morbidity and substance usage.24

Polarity also appears to be important, as one study showed that patients with PMP responded better than patients with PDP to the combination of fluoxetine+olanzapine for the treatment of depressive episodes.18

One of the studies also analysed general prescription data, showing that in PMP the use of the so-called “combined antimanic” drug was more frequent, which are mood stabilisers (lithium, valproic acid, and carbamazepine) and atypical antipsychotics (clozapine, risperidone and olanzapine). However, lamotrigine and quetiapine are prescribed more in PDP and the use of antidepressants is reduced to a small group of patients with BDII and depressive polarity.23 However, there was an article which did not find any differences in the use of mood stabilisers according to polarity type.7

At this point it is worthwhile highlighting the concept of the polarity index (PI) described by Popovic et al.24 The PI is a numerical value given to each drug and which is the result of the ratio between its number required to treat to prevent a depressive episode and its number required to treat to prevent a manic episode. PI values above 1 indicate that this drug is of greater use as an antimanic agent (the atypical antipsychotics for example, and particularly risperidone, aripiprazol and olanzapine), and if the PI value is below 1, then the product is more effective as an antidepressant (lamotrigine). Drugs whose PI value is closer to 1 would have an antimanic power and similar antidepressant power (lithium and quetiapine).24 The study by Popovic et al. Also shows that patients with PMP frequently receive treatment combinations where the PI combined is higher than in patients with PDP, which would indicate a greater antimanic effect in the first group, and this finding was repeated in a different sample.44 Notwithstanding, other authors have doubted the use of the PI, on showing that it is complicated that a single statistical parameter may summarise the enormous variability in response to treatment in disorders as complex as BD.45

DiscussionAt present, not all patients with BD may be classified according to PP, with figures which range between 42.4% and 71.8% in reviewed studies. This may be due to the fact that in certain patients one polarity does not prevail over the other (“nuclear type” patients according to Angst), but it also may be due to the lack of unified criteria amongst the scientific community to define PP, as was shown in a recent publication.46

The so-called “Barcelona proposal” (two thirds criteria) is more specific, and the precision in detecting a real case of PP therefore increases, but at the same time it may be over restrictive, since in several studies where it has been used, it was only possible to classify 56% of patents according to the PP.46 In contrast, looser definitions increase the number of classifiable patients depending on their polarity, but at the risk of this classification being unstable over time and therefore largely irrelevant.7

Some studies have shown there is a higher ratio of PMP with the male, with high educational levels and with BDI, whilst PDP appears to be more associated with females, with being married and with BDII. However, the information provided by long-term follow-up studies47,48 have not been able to replicate these findings, which may be due to the presence of bias in studies included in this review.

The references deliver more consistent data on clinical variables. For example, the onset of depressive symptoms, the most common and prolonged relapses and comorbidity with anxiety disorders or a higher suicide risk are associated with PDP, where a greater delay in diagnosis is also observed. Mixed and melancholic presentations and the use of lamotrigine and quetiapine are also typical of this.

In contrast, the onset of mixed type, a background of the consumption of toxic substances prior to the onset of disease and a better response to atypical antipsychotics and mood stabilisers are characteristic of PMP.

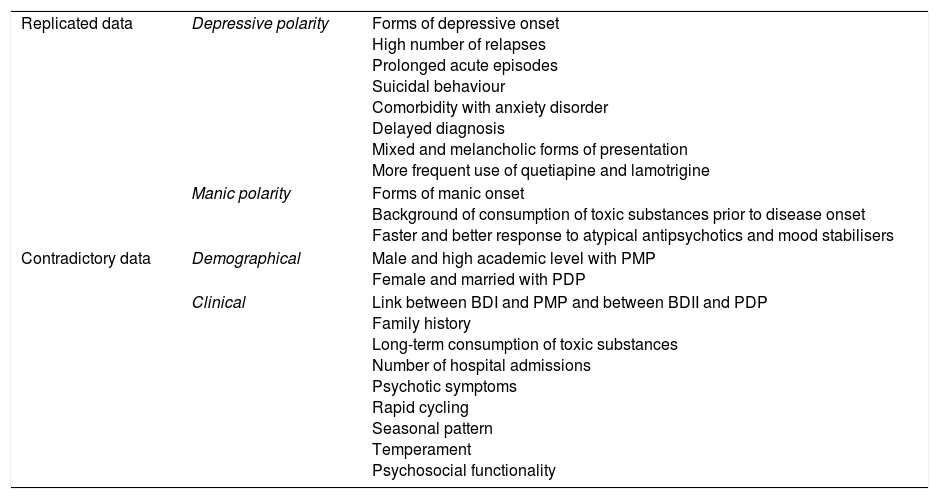

Other factors such as the presence of a family history, long-term abuse of toxic substances, hospital stays, psychotic symptoms, rapid cycling, seasonal patterns, emotional temperaments and level of functionality, show varied information on their relationship with PP (Table 2).

Summary of available evidence: conclusive and contradictory data.

| Replicated data | Depressive polarity | Forms of depressive onset High number of relapses Prolonged acute episodes Suicidal behaviour Comorbidity with anxiety disorder Delayed diagnosis Mixed and melancholic forms of presentation More frequent use of quetiapine and lamotrigine |

| Manic polarity | Forms of manic onset Background of consumption of toxic substances prior to disease onset Faster and better response to atypical antipsychotics and mood stabilisers | |

| Contradictory data | Demographical | Male and high academic level with PMP Female and married with PDP |

| Clinical | Link between BDI and PMP and between BDII and PDP Family history Long-term consumption of toxic substances Number of hospital admissions Psychotic symptoms Rapid cycling Seasonal pattern Temperament Psychosocial functionality |

PDP: predominant depressive polarity; PMP: predominant manic polarity; BD: bipolar disorder.

All these data are in keeping with the results of a recent systematic review13 and demonstrate new lines of research and intervention, among which we would highlight excessive autolysis intent, for its impact in the mortality of patients with BD,49 and especially in those with PDP. Another interesting strategy would be to raise awareness and reduce the consumption of toxic substances in teenagers and young adults due to their long-term association with PMP.13

Although throughout this study we have shown that polarity may be useful as a complement to the current BD classifications, factors such as the absence of a common definition or the lack of objective biological markers have impacted the fact that PP has not been included as an additional encoder in the DSM-5.46 However, a recent meta-analysis has shown that together with the polarity of the first decomposition, analysis of the PP is of great help when selecting an effective treatment to prevent a future relapse.50 According to this study, the risk of a further decompensation is maximum immediately after an episode (hazard ratio 1.89–5.14), particularly during the first year (44%of probability of experience a new relapse of the same polarity during that time).50

ConclusionsThe BD classifications described in the diagnostic manuals provide some information on the characteristics of this disease, and the use of additional encoders, such as PP, may help to complement this information. Throughout this study we have shown the statistically significant relationship of each polarity with different variables of interest in the approach to and treatment of BD, although the literature is not exempt from some contradictory data. This may be due to the absence of a common definition for analysing PP, but a great variety of methodology of the selected articles was also found. Further studies are needed for the future, essentially prospective studies and with a unified definition and methodology, so that reliability may be established for the relationship between PP and the relevant variables in BD patient follow-up.

LimitationsThe main limitation of this study is the fact that it has not been possible to carry out a meta-analysis to provide a higher level of scientific evidence to the results, mainly due to the multiple variables analysed and to the heterogeneity in the methodology of the included articles.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Please cite this article as: García-Jiménez J, Álvarez-Fernández M, Aguado-Bailón L, Gutiérrez-Rojas L. Factores asociados a la polaridad predominante en el trastorno bipolar: una revisión sistemática. Rev Psiquiatr Salud Ment (Barc). 2019;12:52–62.