In the clinical literature, the term gender dysphoria is used to define the perception of rejection that a person has to the fact of being male or female. In children and adolescents, gender identity dysphoria is a complex clinical entity. The result of entity is variable and uncertain, but in the end only a few will be transsexuals in adulthood.

Objectives- -

To review the current status of the aetiology and prevalence, Spanish health care protocols, DSM-V, ICD-10 and international standards.

- -

Psychomedical intervention in under 18 year-olds.

- -

A review of PubMed and UpToDate databases.

- -

Presentation of a clinical case in adolescence woman>man.

- -

There is evidence of a hormonal impact on the aetiology of gender identity dysphoria and an underestimation of its prevalence.

- -

Relevance to DSM-V, including the replacement of the term “gender identity disorder” by “dysphoria gender identity”, and thus the partial removal of the previous disease connotation.

- -

The seventh edition of the international standards World Professional Association for Transgender Health highlights the role of the therapist for advice on the way to the transition.

- -

The Spanish 2012 guide stands out for its wealth of details and explanations, with a language targeted at different professionals.

- -

Dysphoria gender identity must be studied by a multidisciplinary team, in which the psychotherapist must be expert in developmental psychopathology and evaluate emotional and behavioural problems.

En la literatura científica, el término disforia de género se utiliza para definir la percepción de rechazo que tiene una persona respecto al hecho de ser hombre o mujer. En niños y adolescentes la disforia de identidad de género es una entidad clínica compleja, que requiere una correcta respuesta a la demanda que expone el paciente, y cuyo resultado es variable e incierto, pues solo unos pocos casos serán transexuales en la vida adulta.

Objetivos- -

Revisar el estado actual de la etiología y prevalencia, los Protocolos Españoles de Atención Sanitaria, los criterios DSM-V y CIE-10, y los estándares internacionales.

- -

Intervención psicomédica en menores de 18 años.

- -

Revisión bibliográfica: bases de datos PubMed y UpToDate.

- -

Exposición de un caso clínico en la adolescencia mujer>hombre.

- -

Se ha comprobado el impacto hormonal sobre la etiología de la disforia de identidad de género y la infraestimación de su prevalencia.

- -

Relevancia de los criterios diagnósticos del DSM-V, que incluyen la sustitución del término «trastorno de identidad de género» por «disforia de identidad de género», y con ello, la eliminación parcial de la anterior patologización.

- -

La séptima edición de los estándares internacionales de la World Professional Association for Transgender Health resalta el papel del psicoterapeuta en el asesoramiento durante el camino hacia la transición.

- -

La Guía Española 2012 se distingue por su riqueza en los detalles y explicaciones, con lenguaje dirigido a los diferentes profesionales.

- -

La disforia de identidad de género debe ser atendida por un equipo multidisciplinar en el que el psicoterapeuta debe ser experto en psicopatología del desarrollo y evaluar problemas emocionales y de comportamiento.

Transsexuality is not a new phenomenon, as it has existed since the distant past and in different cultures. The term “transsexual” started to be used in 1940 to refer to individuals who wished to live permanently as members of the opposite sex, so that there is incongruence between the sex they were born with and the sex they feel they belong to. The feeling of belonging to a certain sex in biological and psychological terms is termed gender or sexual identity.

The term “gender identity dysphoria” was proposed in 1973. This includes transsexuality together with other gender disorders. Gender dysphoria is the term used to designate the dissatisfaction arising from the conflict between gender identity and assigned sex.1

In 1980 transsexuality appeared as a diagnosis in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM)-III. The next revision of this manual (DSM-IV) in 1994 did not use the term “transsexuality”, which it replaced by the term gender identity disorder.2 The International Classification of Diseases (ICD)-10 mentions 5 types of gender identity disorder, and it uses the term transsexuality (F64.0) for one of them.3

This term is replaced in the DSM-V by gender identity dysphoria (GID), thereby helping to depathologise this entity in general.4

Caring for individuals with GID involves ensuring a correct response to the demands expressed by the patient. Care for minors with this condition adds other differentiating characteristics that will influence examination and the subsequent approach. According to several studies sexual identity appears at from 2 to 3 years of age. GID is a highly complex entity in children and adolescents. It may give rise to problems in terms of the ability to talk about their condition, and this is often based on the subjective discourse of parents or their tutors. Although the results of these manifestations are variable and uncertain, only a few individuals will eventually be transsexuals. As minors are developing the presupposition is that everything about them is immature, unstable and changing.5 Professionals who see a case of this type must on the one hand offer a definite diagnosis which confirms the situation of the minor, while on the other hand making the family feel secure, so that the diagnosis is both true and permanent over time.

ObjectivesDiagnostic classification manuals are one of the instruments used as guides in the diagnostic process prior to therapeutic intervention. The aim of this paper is to describe, analyse and reflect on the diagnosis of GID using the different versions of these manuals, paying special attention to the approach used in infancy and adolescence.

Methodology- •

Revision of the bibliography used the PubMed and UpToDate databases.

- •

Presentation of a case during adolescence (woman>man).

Several theories have been used in the attempt to explain the origin of GID. No genetic sexual alteration has yet been detected, and the karyotype is the one that corresponds to biological sex. We know that a gene is responsible for turning an undifferentiated gonad into a testicle (if it is present) or into an ovary (if it is absent). Differences have been shown to exist in certain brain structures between individuals with different sexual orientation. Transsexuality may originate during the foetal stage in the form of an alteration which hormonally impregnates the brain with a sexuality other than the genital one. Moreover, different influences during critical periods of development such as pregnancy, infancy or puberty may affect behaviour and sexual orientation. Prenatal stress, the mother – child relationship during the early stages of life, family influences or sexual abuse during childhood or puberty may determine adult sexual behaviour. Thus sufficient data support the hypothesis that sexual orientation and identity may have a biological substrate (genetic, cerebral or hormonal) which is influenced by certain environmental, social and family factors during what are known as the “sensitive periods” of life, forming sexual orientation and identity together with definitive adult sexual identity.1 GID may therefore develop as the result of an altered interaction between genetic factors, brain development and the action of sex hormones. This has been shown by several scientific studies,6 although statistical confirmation is still needed as the number of studies undertaken is insufficient (the hypothesis being that GID aetiology is based on neurobiological sexual differentiation).7

EpidemiologyFormal epidemiological studies on non-conformity with gender are lacking. Exact estimation of its prevalence is hindered by the social stigma attached to gender non-conformity and the lack of a standard definition. Estimations of frequency vary widely, depending on the definition used and the population studied.1,8

Two key points stand out from the revision of the available studies: (1) an increasing number of children and adolescents visit multidisciplinary clinics for the evaluation and management of gender identity problems, and (2) while many children and adolescents sometimes behave as if they were members of the opposite sex, significantly fewer of them go on to desire physical or social transition to the opposite sex during adolescence or adulthood.

Treatment in Spain: protocols, guides and diagnostic criteriaOn 28 September 2011 the European Parliament passed a binding text for all member states on sexual orientation and gender identity. In point 13 this states that the EU: “Condemns with the utmost severity the fact that some countries, even ones in the EU, still consider homosexuality, bisexuality or transsexuality to be a mental disease, and it requests the different states to combat this phenomenon: most particularly it requests that transsexual and transgender experiences be de-psychiatrised, free choice of the team in charge of treatment, simplification of the change of identity and coverage by the social security system”.9

We are progressing towards a substantial step that requires the reformulation of Spanish protocols and standards for treating people with GID in many aspects, including the de-pathologisation of GID in general. This has already been passed by different European parliaments including the Spanish parliament (15/03/2010) and those of some of the autonomous communities in the country.

The diagnostic criteria used in the fifth edition of the DSM are relevant. These include the replacement of the term “gender identity disorder” with “gender identity dysphoria”, thereby partially eliminating the previous implication of mental pathology.4,10

Section F64 of the ICD-10 applies almost the same change, although it is unclear whether GID is included in the new context following its re-definition as no longer a mental disorder.10

The seventh edition of Care Standards was published in September 2011 by the World Professional Association for Transgender Health. These are standards of care for the healthcare of transsexual and transgender individuals as well as those with gender non-conformity, and they include a specific chapter on the care and treatment of children and adolescents with GID. Although psychotherapy disappears as an eligibility criterion, they underline the fact that apart from making the diagnosis, psychiatrists or clinical psychologists also advise patients to help them in their transition as far as is possible. International standards recommend:

- -

A positive evaluation of GID that makes it possible to confirm the suitability of hormone therapy, together with patient consent, all in a letter to the endocrinology specialist that also requests that the mental health specialist confirms this by telephone if he does not form a part of the multidisciplinary team in the same hospital.

- -

No period of real-life experience is required, as this term has been completely eliminated from the seventh version of the Care Standards (the sixth version required having lived for 3 months in the desired role of the opposite sex [real-life experience] or having undergone 3 months of psychotherapy before the administration of hormones, as well as diagnosis and examination by the clinical specialist); hormone treatment is only a recommendable criterion, and it is not obligatory. For sex reassignment surgery it is necessary to have lived for one year in the role of the desired sex, apart from recommendation by the mental health specialist.11

- -

Eligibility for access to relatively minor surgical operations (mastectomy or mammoplasty) requires: documentation accrediting persistent GID, patient capacity to take informed decisions, a minimum age and, if concomitant psychopathologies exist, they have to be properly controlled. At least 12 months of hormone therapy is required in the case of mammoplasty so that the breasts can develop sufficiently.

- -

There are different requisites for sex reassignment surgery depending on the operation in question:

- •

Ovariectomy-hysterectomy and orchiectomy: 2 independent psychomedical reports are required together with uninterrupted hormone therapy during at least 12 months (unless contraindications exist, the patient experiences a reaction or lacks resources).

- •

Genital sex reassignment (phalloplasty or vaginoplasty): apart from the evaluation of GID and continuous hormone therapy during 12 months, this requires having lived uninterruptedly for one year in the gender role congruent with the gender identity of the patient. The whole process (evaluation of GID, hormone therapy and living in the desired role) may be completed in one year, with multidisciplinary collaboration by different doctors.10,11

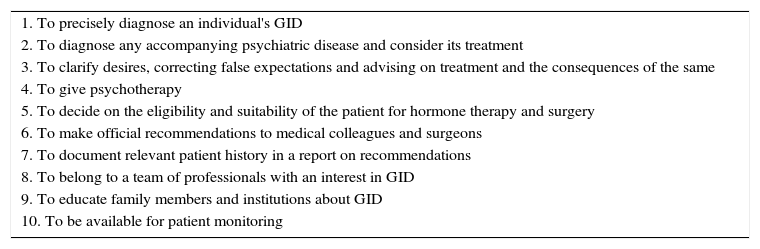

The new 2012 Spanish guide for the care of individuals with GID, which updates the first version of the guide that was published in 2003, stands out for its richness of details and numerous explanations, as well as because it is written in a language aimed at the different specialists involved (psychiatrists, psychologists and plastic surgeons, etc.)1 This guide underlines the 10 functions of Mental Health Specialists (Meyer et al., 2001) (Table 1).1,5 Psychotherapy does not attempt to cure GID, but rather help the individual to feel better in their identity and face other different problems, clarifying and relieving conflicts.1

The 10 functions of Mental Health Workers.

| 1. To precisely diagnose an individual's GID |

| 2. To diagnose any accompanying psychiatric disease and consider its treatment |

| 3. To clarify desires, correcting false expectations and advising on treatment and the consequences of the same |

| 4. To give psychotherapy |

| 5. To decide on the eligibility and suitability of the patient for hormone therapy and surgery |

| 6. To make official recommendations to medical colleagues and surgeons |

| 7. To document relevant patient history in a report on recommendations |

| 8. To belong to a team of professionals with an interest in GID |

| 9. To educate family members and institutions about GID |

| 10. To be available for patient monitoring |

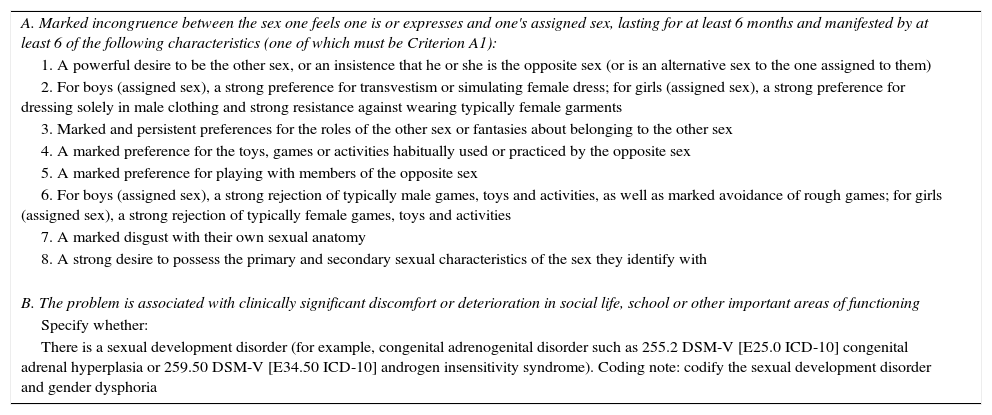

The DSM-V (APA, 2013) includes the following diagnoses within the category of “gender dysphoria”: gender dysphoria in children, gender dysphoria in adolescents or adults, non-specific gender dysphoria and other specific gender dysphoria.4 As well as changing the name of the diagnosis by eliminating the term “disorder”, dysphoria in children has its own criteria (Table 2). It sets a time criterion of 6 months and requires 6 of the 8 indicators in criterion A. The presence of the first indicator (A1) is a necessary but not sufficient condition for the diagnosis. This makes the 2 criteria which refer to physical anatomy or sexual characteristics unnecessary. Unlike the previous manuals, the DSM-V does not exclude people with sexual differentiation disorders.12

Gender dysphoria in children, 302.6 DSM-V (F64.2 ICD-10).

| A. Marked incongruence between the sex one feels one is or expresses and one's assigned sex, lasting for at least 6 months and manifested by at least 6 of the following characteristics (one of which must be Criterion A1): |

| 1. A powerful desire to be the other sex, or an insistence that he or she is the opposite sex (or is an alternative sex to the one assigned to them) |

| 2. For boys (assigned sex), a strong preference for transvestism or simulating female dress; for girls (assigned sex), a strong preference for dressing solely in male clothing and strong resistance against wearing typically female garments |

| 3. Marked and persistent preferences for the roles of the other sex or fantasies about belonging to the other sex |

| 4. A marked preference for the toys, games or activities habitually used or practiced by the opposite sex |

| 5. A marked preference for playing with members of the opposite sex |

| 6. For boys (assigned sex), a strong rejection of typically male games, toys and activities, as well as marked avoidance of rough games; for girls (assigned sex), a strong rejection of typically female games, toys and activities |

| 7. A marked disgust with their own sexual anatomy |

| 8. A strong desire to possess the primary and secondary sexual characteristics of the sex they identify with |

| B. The problem is associated with clinically significant discomfort or deterioration in social life, school or other important areas of functioning |

| Specify whether: |

| There is a sexual development disorder (for example, congenital adrenogenital disorder such as 255.2 DSM-V [E25.0 ICD-10] congenital adrenal hyperplasia or 259.50 DSM-V [E34.50 ICD-10] androgen insensitivity syndrome). Coding note: codify the sexual development disorder and gender dysphoria |

It is not clear exactly when children learn about gender. Nevertheless, they are aware of gender differences during infancy. At 2.5 years old they are able to label faces as a man or woman. Children aged from 2 to 4 years old start to understand gender differences and use pronouns such as “he” and “she”, and they can also identify their own gender. At this age the majority of children play with the toys and games that correspond to their anatomic sex. Although at first children may consider gender to be subject to variation and change, by the age of 5 or 6 years old their vision of gender is more constant.

Young children accept gender stereotypes for themselves and others; preschool children start sexual segregation, playing more with their companions of the same sex. They promote social constructions that can be generalised together with roles and rules that fit their gender. At school age children may make gender norms more flexible, considering gender-based activities with a more flexible attitude as subject to choice. However, peer groups in general are still composed of same-sex individuals; following the rules, fitting in and acceptance by the peer group are all important for school-age children.

Exploring sexuality, including gender and sexual behaviours, is a normal part of children's development. At some time during childhood many children experiment with gender expression and roles (such as with the toys and games of the other sex, transvestism). Nevertheless, due probably to unknown biological, psychosocial or multifactorial reasons, in some children trans-gender behaviour and expression is more consistent, persistent and insistent than it is among their peers. These are not per se the result of decisions, but rather reflect an innate preference of the child.13

A reliable diagnosis of GID is based on evaluation by clinical interview with detailed anamnesis of all areas of patient history and their life story. Other techniques are used as well, such as everyday diaries, recording items that describe the mood of the minor, as well as the level of discomfort they experience in their everyday life. This information will be supplied by the patient as well as by their family.12

The psychotherapist must be an expert in children's and adolescent's development psychopathology, and they must recognise and accept gender identity problems. Emotional and behavioural problems may arise in connection with family conflicts, which must be assessed. In these cases the diagnostic phase may be prolonged, and treatment must have the aim of resolving other factors that may cause discomfort. The child and their family will need support when facing difficult social decisions.14,15 Because of the high level of variability in the result and the speed with which gender identity change can occur in adolescents, it is recommended that any physical intervention be delayed for as long as possible. These interventions may take the form of:

- 1.

Completely reversible interventions: the use of LHRH analogues or medroxyprogesterone to suppress the production of estrogens or testosterone and thereby halt the physical changes that occur during puberty.

- 2.

Partially reversible interventions: the use of masculinising or effeminising hormones. Some of the resulting changes would require surgical treatment to be reversed.

- 3.

Intervenciones reversibles: procedimientos quirúrgicos. Irreversible interventions: surgical procedures.

It is recommendable that children with gender identity problems should not be treated using physical interventions until they are at least 16 years old. The progress from one step to another should be gradual, and should only occur when the family and patient have had time to assimilate the effects of the previous interventions. Treatment with LHRH analogues must not be commenced prior to Tanner stage II, so that the adolescent experiences the start of puberty in their own biological sex. This approach makes it possible to gain time to carry on exploring the gender identity of the subject and other aspects of their development in psychotherapy, so that transition to the opposite sex will be easier if this goes ahead.1 However, according to the recommendations of the World Professional Association for Transgender Health, intervention may have a positive effect on the psychological well-being and social functioning of the patient, as delaying or minimising medical interventions in adolescents with GID may prolong their gender dysphoria and contribute to the development of a physical appearance which encourages abuse and stigmatisation (World Professional Association for Transgender Health, 2011).11 The following conditions must be fulfilled before administering LHRH analogues:

- -

During infancy the adolescent displayed an intense pattern of opposite sex identity and aversion to the expected social role of their own gender.

- -

When puberty commenced their discomfort with their gender and sex greatly increased.

- -

Their family accepts and takes part in therapy.

A second step may commence after the age of 16 years old is reached, with the parents’ consent. No surgical procedures may be performed before adulthood (18 years old).1,16 The clinical evaluation of all patients under the age of 18 years old who fulfil GID criteria must include the following items:

- -

Clinical history centring on the development of gender identity, psychosexual development (including sexual orientation) and aspects of everyday life.

- -

Physical examination: gynaecological, andrological/urological and endocrinological.

- -

Clinical evaluation from the psychiatric/psychological point of view to detect psycho-pathological problems.17,18

A 16 year-old female referred due to “anxiety in connection with her bodily image”.

Personal history- -

Somatic: no known drug allergy, no relevant diseases. Menarche at 11 years old. Irregular periods. No consumption of toxic substances.

- -

Psychological: she visited our Mental Health Unit at the age of 13 years old with an initial diagnosis of gender identity disorder (DSM-IV).

- -

Social and at work: first year of A level studies, good academic results until this year. Recently left school.

Mother aged 55 years old, healthy, a secretary. Father aged 55 years old, healthy, a lawyer. She is their only child.

Current diseaseFrom the age of 5 she has displayed a marked preference for playing boys’ games with boys (“they gave her dolls and she broke them”), refusing to wear dresses or her hair long. At 6–7 years old she liked playing football, karate and basketball. At 11 years old she started to reject the growth of her breasts and used compression garments to hide them, together with loose clothing, and in summer she did not want to go to the swimming pool. At 13 years old her friends started to call her by a male name she had chosen, but her parents still use her female name, although they do support her. She has had several relationships with heterosexual girls and currently has a girlfriend. She mentions rejection and social isolation at school and secondary school, so that she decided to leave school and cease studying.

Psychopathological examinationIn the first interview she is aware, allo- and auto-psychically oriented, approachable and collaborative. She requested that she be referred to as a man, using the male name she had chosen. Fluid coherent discourse, suitable for her stage of development. Male appearance, with boy's clothing, short hair and male gait. Clear identification with the male sex and rejection of her own sex. No symptoms of depression. A mild state of anxiety, feelings of impotence and discomfort associated with the rejection she feels. Displays no psychotic disorders or personality pathologies. No autolytic ideas.

Complementary examinationsPsychometrics: WISC-R: PV 141; PM 123; PT137. ESPQ: high intelligence, abstract thought. “Brilliant”, swift understanding and learning of ideas. STAI: significant scores for state-anxiety. Human Figure Test (Fig. 1).

Endocrinology: biochemistry, haemogram and hormonal values normal. Karyotype 46 XX. The decision was taken together with her parents to start im/14 week hormone therapy with testosterone.

DiagnosisGender dysphoria (F64.1, transsexuality f>m).

Evolution and treatmentDuring 2 years the patient received regular examinations in our Mental Health Unit, in Psychology and Psychiatry, and is being monitored by the Endocrinology Department, continuing with transsexual hormone therapy. The patient's mood has improved significantly, and he has begun studying again in the Adult School where, following the requisite administrative measures, his male name is used. During this time interventions with the family have also taken place, and they now use his male name. After recently reaching the age of 18 years old he was operated for mammoplasty and expressed satisfaction with the results obtained.

ConclusionsPatients with GID must be cared for by a multidisciplinary team (psychology, psychiatry, endocrinology and surgery). The psychiatrist or psychologist usually sees them first, and if the patient consults an endocrinologist, they will be referred to a psychiatrist/psychologist who will commence working with them. The responsibility for the decision to start hormone and surgical therapy is shared with the doctor who prescribes it. Hormone treatment usually relieves the anxiety and depression of these patients without the need for additional medication. Although the existence of another psycho-pathology does not rule out surgery, it may delay it.

Psychotherapy aims to help the individual to feel better in their identity and confront other different problems, clarifying and relieving conflicts. When caring for minors monitoring over time is indispensable for a reliable diagnosis, and they cannot be evaluated at a single point in time.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments took place in human beings or animals for this research.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they followed the protocols of their centre of work governing the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that this paper contains no patient data.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Sánchez Lorenzo I, Mora Mesa JJ, Oviedo de Lúcas O. Atención psicomédica en la disforia de identidad de género durante la adolescencia. Rev Psiquiatr Salud Ment (Barc). 2017;10:96–103