Up to 80% of first-episode psychosis patients suffer a relapse within five years of the remission. Relapse should be an important focus of prevention given the potential harm to the patient and family. It threatens to disrupt their psychosocial recovery, increases the risk of resistance to treatment and has been associated with greater direct and indirect costs for society.

Based on a previous project entitled “Genotype–phenotype and environment. Application to a predictive model in first psychotic episodes” (PEPs Project), the project “Clinical and neurobiological determinants of second episodes of schizophrenia. Longitudinal study of first episode of psychosis” was designed, also known as the 2EPs Project. It aimed to identify and characterize those factors that predict a relapse within the years immediately following a first episode. This project has focused on following the clinical course, with neuropsychological assessments, biological and neuroanatomical measures, genetic adherence and physical health monitoring in order to compare a subgroup of patients with a second episode to another group of patients which remains in remission. The main objective of the present article is to describe the rationale of the 2EPs Project, explaining the measurement approach adopted and providing an overview of the selected clinical and functional measures.

2EPs Project is a multicenter, coordinated, naturalistic, longitudinal follow-up study over three years in a Spanish sample of patients in remission after a first-psychotic episode of schizophrenia. It is closely monitoring the clinical course of the cases recruited to compare the subgroup of patients with a second episode to that which remains in remission. The sample is composed of 223 subjects recruited from 15 clinical centres in Spain with experience of the preceding PEPs Study project, albeit 2EPs being an expanded version with new basic groups in biological research. From the total sample recruited, 63 patients presented a relapse (44%).

2EPs arose to characterize first episodes in an exhaustive, novel and multimodal way, thus contributing towards the development of a predictive model of relapse. Identifying the characteristics of patients who relapse could improve early detection and intervention.

Hasta el 80% de los pacientes con un primer episodio de psicosis experimentan una recaída dentro del plazo de 5 años desde la remisión. Dicha recidiva debería constituir un importante enfoque de prevención, dado el daño potencial al paciente y sus familiares, ya que amenaza con perturbar su recuperación psicosocial, incrementa el riesgo de resistencia al tratamiento y se ha asociado a mayores costes directos e indirectos para la sociedad.

Basado en un proyecto anterior denominado «Genotipo-fenotipo y entorno. Aplicación a un modelo predictivo en primeros episodios psicóticos –Proyecto PEPs–» (Genotype-phenotype and environment. Application to a predictive model in first psychotic episodes –PEPs Project–), se diseñó el proyecto «Determinantes clínicos y neurobiológicos de segundos episodios de esquizofrenia. Estudio longitudinal del primer episodio de psicosis» (Clinical and neurobiological determinants of second episodes of schizophrenia. Longitudinal study of first episode of psychosis), también conocido como proyecto 2EPs. Su objetivo fue identificar y caracterizar aquellos factores predictivos de recaída dentro del periodo inmediatamente posterior al primer episodio. Este proyecto se centró también en el seguimiento de la evolución clínica, con evaluaciones neuropsicológicas, medidas biológicas y neuroanatómicas, adherencia genética y supervisión de la salud física, a fin de comparar un subgrupo de pacientes que había tenido un segundo episodio con otro grupo de pacientes que sigue en remisión. El principal objetivo del presente artículo es describir el fundamento del Proyecto 2EPs, explicando el enfoque de medición adoptado y aportando una perspectiva general de las medidas clínicas y funcionales seleccionadas.

El Proyecto 2EPs es un estudio multicéntrico, coordinado, naturalista y de seguimiento longitudinal, realizado a lo largo de 3 años, en una muestra de pacientes españoles en remisión tras un primer episodio psicótico de esquizofrenia. Supervisa estrechamente la evolución clínica de los casos seleccionados, para comparar el subgrupo de pacientes que había presentado un segundo episodio con aquellos que siguen en remisión. La muestra se compone de 223 sujetos seleccionados de 15 centros clínicos en España con experiencia en el proyecto del Estudio PEPs anterior, aunque el Proyecto 2EPs constituye una versión ampliada con nuevos grupos básicos en investigación biológica. De la muestra total seleccionada, 63 pacientes presentaron una recaída (44%).

El Proyecto 2EPs surgió para caracterizar los primeros episodios de modo exhaustivo, novedoso y multimodal, contribuyendo así al desarrollo de un modelo predictivo de una recaída. Identificar las características de los pacientes con recidiva podría mejorar la detección e intervención tempranas.

First-episode psychosis (FEP) represents one of the main challenges for mental health.1 Its symptoms are grouped as positive, negative, cognitive and affective. FEP can occur at any age, but most people develop it when they are young (80% of first episodes of psychoses occur between 16 and 30 years of age), disrupting their achievement of crucial educational, occupational, and social milestones.2 Without an appropriate differential diagnosis and early intervention, clinical development after a FEP can lead to a chronic condition of varied signs and symptoms.3 For that reason, the early stages of psychosis are often considered to be a “critical period”.4 It has been shown that a late intervention for this population can greatly reduce the quality of life of patients and their families, as well as involve a high cost for society,5,6 representing 11.2% of the global burden of brain disorders in Europe.7

Around 3% of the general population suffers a psychotic episode during their lifetime.8 Psychosis is seen in several psychiatric disorders, including schizophrenia spectrum disorders (i.e., schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, delusional disorder, schizophreniform disorder, and brief psychotic disorder), bipolar disorder, and major depression with psychotic features. The lifetime prevalence was around 2% for non-affective psychotic disorders and 0.59% for affective psychotic disorders.8

The clinical evolution after a first episode of schizophrenia (FES) tends to be chronic and variable. Complete remission only occurs in one third of the patients.9 Relapse rates are higher in this critical period after the onset of the illness than in other periods, ranging from 30% to 60% at two years10,11 and up to 80% during the first five years after onset of the illness.12–14 Relapse, characterised by acute psychotic exacerbation, may have devastating repercussions, such as the progressive worsening of personal relationships, education or employment status.15 Additionally, it is associated with a higher risk of chronic or persistent symptoms, progressive functional deterioration and declining or resistance treatment response.16,17 Given the potential harm to the patient and family, second episodes should be an important focus of prevention. They threaten to disrupt psychosocial recovery and also increase the economic costs.18 The FES population represents a unique opportunity to study the clinical variables and the functional outcomes of psychotic disorders and to prevent potential relapses.

Several studies have focused on determining prognostic factors after a FEP. Being male, having greater clinical severity at onset, more negative symptoms at onset, worse premorbid adjustment, worse cognitive performance, lower cognitive reserve, longer duration of untreated psychosis (DUP), alcohol and drug use and poor insight have been related to worse outcome.19–31 More specifically, numerous studies have focused on analyzing risk factors for relapse in FEP. A systematic review and meta-analysis reported that clinical variables and general demographic variables including age of onset, gender, marital status, and employment have little impact on relapse rates. Conversely, non-adhesion with medication – using the reported level of adherence and/or the saliva/plasmatic levels of antipsychotic–, persistent substance use disorder, careers’ criticism and poorer premorbid adjustment significantly increase the risk of relapse in FEP.32 It was found that the most common risk factor by far was antipsychotic medication discontinuation.14,33,34 Thus, adherence and other factors that predispose individuals to relapse should be a major focus of attention in managing schizophrenia.35

Bearing in mind what is stated above and the fact that the first step in preventing negative consequences of a psychotic disorder is to characterize the population, the “Genotype–phenotype and environment interaction. Application of a predictive model in first-episode psychosis” project (also called the PEPs Project) arose the years ago, funded by the Healthcare Research Fund (Spanish acronym, FIS; PI08/0208). It was conducted in the context of the Centre for Biomedical Research in Mental Health Network (Spanish acronym, CIBERSAM) – which promotes collaborative and translational biomedical research of high quality-, and based on the previous experience of the Network of Research in Mental Disorders (Spanish acronym, REM-TAP).36 The main goal for the PEPs Project was to identify genetic and environmental factors of risk and their interaction in the appearance of a FEP, with the purpose of developing more effective strategies of differential diagnosis and treatment. The complete protocol of assessment is extensively described in Bernardo et al. (2013).37

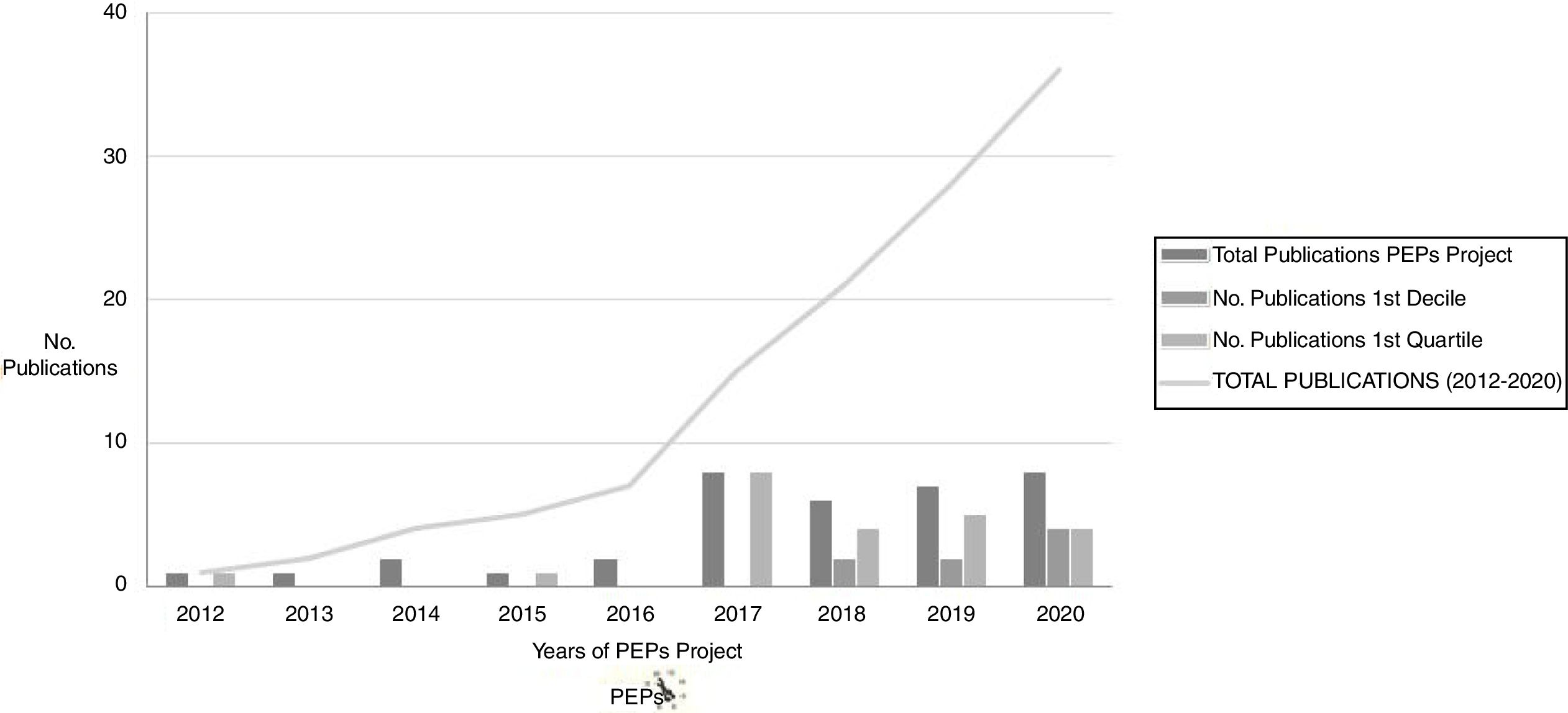

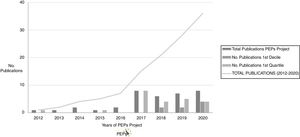

Numerous results derived from the PEPs Project have been as yet published (and the project is still currently producing relevant data) in different high-impact national and international journals (see Fig. 1). The publications derived from the PEPs Project have achieved a total impact of more than 330 with over 300 citations in total. A review of the main results and publications of the PEPs Project can be found in Bernardo et al. (2019).6

Number of publications derived from the PEPs Project. Numerous results derived from the PEPs Project have been published. The publications derived from the PEPs have achieved a total impact of more than 330 and total citations of more than 300. The most cited topics are: pharmacogenetics, genetic predictors of biological markers, general cognition in first episode psychosis, negative symptomatology, functional outcomes and cognitive reserve.

In this context, and following similar methods, the “Clinical and neurobiological determinants of second schizophrenia episodes. Longitudinal study on first-episode psychosis” (2EPs Project) was developed. It was funded by the Healthcare Research Fund (PI11/00325).

The purpose of the present article is to describe the rationale for the measurement approach adopted for the 2EPs Project, providing an overview of the selected clinical and functional measures used.

Study design and rationaleThe 2EPs is a multicenter, coordinated, longitudinal follow-up study of three years’ duration with a Spanish sample of patients in remission after a FES. It was designed and conducted between 2011 and 2016, with the main purpose of identifying useful predictive and therapeutic strategies to guide clinical practice and to prevent a worsening in the long-term course.

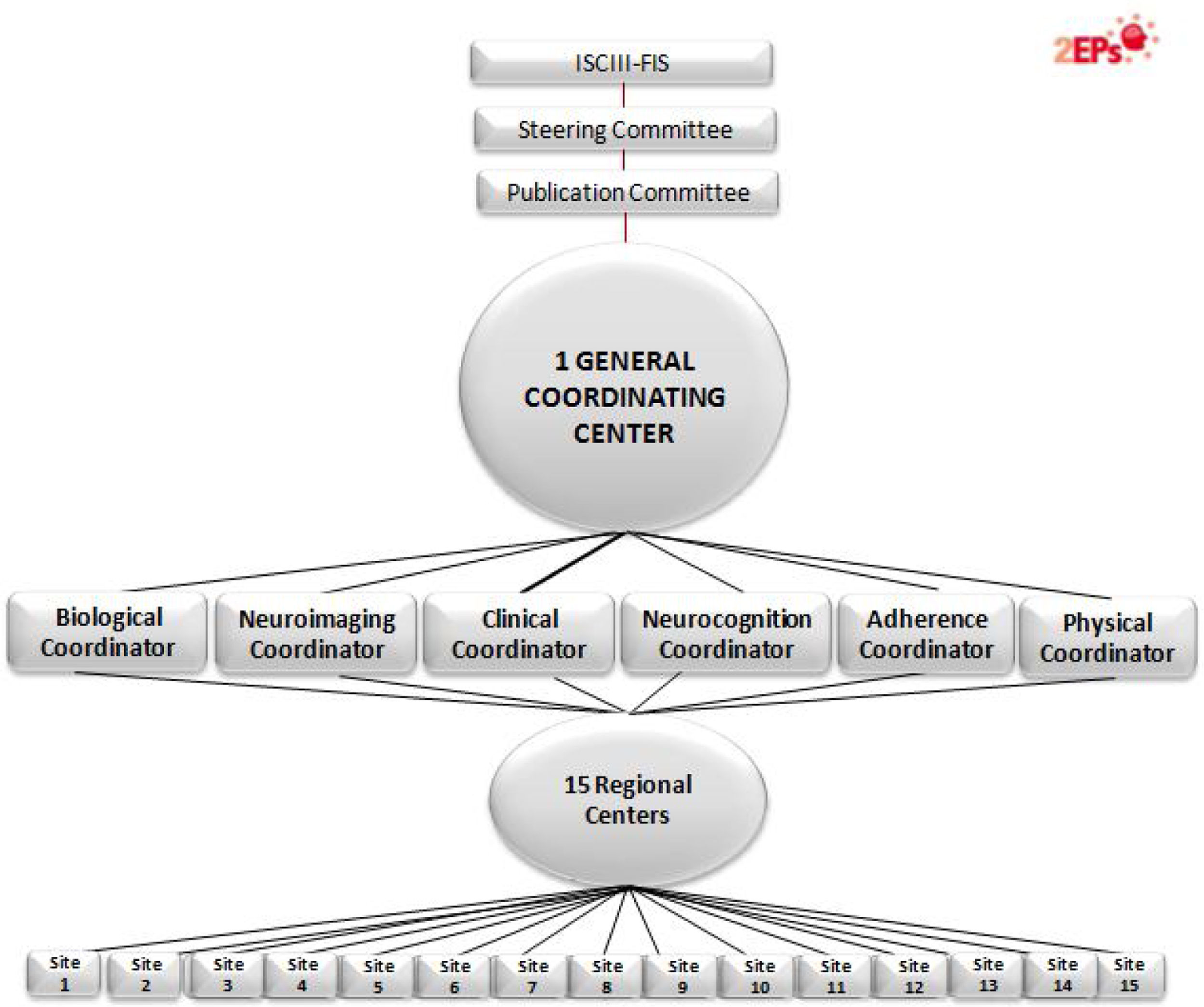

Specifically, the 2EPs Project has the following objectives: (a) to elaborate a predictive model of second-episode appearance based on clinical characteristics and global functioning; (b) to study neuropsychological profiles related to clinical, diagnostic, global functioning and genetic variables in this cohort of patients who have remitted from a FES, characterizing the profiles of those who relapse and those who do not; (c) to describe genotypic profiles in dopaminergic, serotoninergic and noradrenergic neurotransmission of interest for their roles in the prevention of or propensity to relapse due to psychotic exacerbations, stratifying the sample according to course of illness and sociodemographic and clinical characteristics; (d) to determine the relationship between the genetic polymorphisms involved in the pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic phases of the response, as well as the adverse effects of antipsychotic treatment after a FES; (e) to analyze the role of the treatment and the appearance of a new episode; (f) to identify genetic, neuropsychological and clinical variables that predict brain volumes and structural changes during the first three years of follow-up after the appearance of a FES, and (g) to identify the psychosocial interventions that are carried out during the first years of follow-up after the appearance of a FES and assess its relationship with the presence of psychotic relapses and other clinical outcome variables. Fifteen centers participated, coordinated from the Hospital Clínic from Barcelona.

Patients were followed up for 3 years (± 3 months of flexibility) or until relapse (± 3 months of flexibility), whichever happened first, with visits every 3 months (4 visits per year) since the period established between these visits was considered sufficient to detect a relapse. A protocol of telephone calls between visits – or in case patients did not attend the follow-up visit – was implemented in order to detect the highest possible number of relapses and so as not to lose information during the follow-up.

The project includes multiple sub-studies, distributed in a structure of 6 modules. Some sites participated in all the modules and other sites in part of them. The General and basic module assesses the presence or absence of relapses and includes the clinical assessments, evaluation of global functioning, genetic risk and the pharmacogenetics of efficacy and side effects. A second, the Neuroimaging module encompasses the analysis of brain structures for cases at the time of relapse or at end-visit (3-years) using magnetic resonance imaging. The Neurocognition module determines cognitive profiles related to a greater likelihood of having a relapse. A fourth, the Adherence module, aims to establish antipsychotic drug levels in saliva as a method of monitoring drug compliance and assessing the potential benefits of psychoeducational and psychological treatments; the fifth module, the Biological, searches for biomarkers potentially involved in relapses, as anti-inflammatory processes, epigenetics and neurotrophins. The last module is dedicated to Physical health; it was designed to assess whether there is a subgroup of patients with schizophrenia with the comorbid diagnosis of anxiety, which is associated with the same physical disorders frequently associated with schizophrenia. This fact would help to explain part of the increase in morbidity and mortality in schizophrenia. Another purpose of this module is to determine the relationship of the genetic polymorphisms involved in the pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic phases of the response, as well as the adverse effects on physical health of antipsychotic treatment after a FES: extrapyramidal, cardiological, metabolic and hormonal. Another goal is to study the relationship between the appearance of side effects, the abandonment of treatment and the appearance of a new episode, and to identify the psychosocial interventions that are carried out during the first years of follow-up and assess their relationship with the presence of psychotic relapses and physical health.

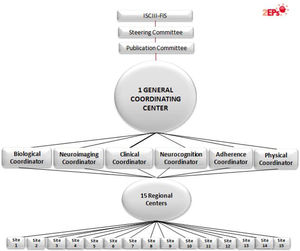

The analysis of all this data promises to help to define early interventions centered on preventing second episodes of schizophrenia (see Fig. 2).

2EPs Project organization. 15 regional centers recruited patients: Hospital Clínic from Barcelona (main 2EPs coordinator and General/Clinical and Physical Health module coordinator); omplejo Hospitalario de Navarra (Neurocognition module coordinator); Hospital Gregorio Marañón (Neuroimaging module coordinator); Hospital Santiago Apóstol (Adherence module coordinator); Hospital Clínico y Universitario de Zaragoza; Hospital Ramón y Cajal; Universidad del Pais Vasco; Hospital de Sant Pau; Hospital Benito-Menni; Hospital Doce de Octubre; Hospital Sant Joan de Déu; Universidad de Oviedo; Hospital Clínico de Valencia; Hospital de Bellvitge, and Hospital del Mar. An additional group, Universidad de Cádiz, participated as a basic group and was the Biological module coordinator.

A total of 223 subjects with a diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizophreniform disorder were included in the 2EPs Project. From October 2012 to December 2015, the fifteen centers participating in the recruitment prospectively attended patients from each center and included those with a FES. Patients who met the inclusion criteria and were attended at these facilities during the recruitment period were invited to participate in the study.

The inclusion criteria were: (a) aged between 16 and 40 years at the time of first assessment (baseline visit); (b) met diagnostic criteria according to DSM-IV for schizophrenia or schizophreniform disorder38; (c) in remission from the first psychotic episode (which it should have been presented in the last 5 years) according to Andreassen criteria.39 Symptomatic remission is achieved when the following criteria is fulfilled: mild severity (score of 3 or lower) in 8 items of the Positive and Negative Symptoms Scale Positive and Negative Symptoms Scale (PANSS) (e.g., delusions, unusual thought content, hallucinatory behavior, mannerisms/posturing, blunted affect, social withdrawal, lack of spontaneity).40 There is a minimum time threshold of 6 months in which the symptoms of severity must be maintained; (d) not having relapsed after the first psychotic episode; (e) Spanish spoken correctly, and (f) provide the signed informed consent.

The exclusion criteria were: (a) having experienced a traumatic brain injury with loss of consciousness; (b) presenting intellectual disability defined by an estimated Intelligent Quotient (IQ)<70, together with malfunctioning and difficulties with adaptive process, and/or (c) presenting somatic pathology with mental repercussion.

Since this was a naturalistic study, there were no guidelines for the treatment administered (pharmacological and/or psychological).

The study was approved by the investigation ethics committees of all participating clinical centres. Informed consent was obtained from all participants. For children under the age of 16, parents or legal guardians gave written informed consent before the beginning of their participation in the study, and patients assented to participate. The genetic part had a specific informed consent form. When requested, participants in the study were given a report on the results of the tests.

Characteristics of the sampleFollowing the inclusion and exclusion criteria detailed above, a total of 223 persons (68% male) were included in the 2EPs Project. 80 discontinued or dropped out of the study, particularly due to a loss of follow-up or refusal of re-evaluation. From the total who completed the follow-up (143 subjects), 63 patients presented a relapse (44%). The mean age of our sample was 25.94±6.04 years and the mean age at first episode was 24.54±5.77 years. Seventy-nine percent of patients showed medium-low or low socioeconomic status and the average DUP was determined as 196.95±375 days (28 weeks approximately). 17% reported cannabis use. As per inclusion criteria, all patients were in remission according to Andreassen criteria; the mean scores were 9.39±2.93 in the PANSS positive, 13.63±5.08 in the PANSS negative, 24.33±6.98 in the PANSS general psychopathology subscale and 47.35±13.08 in the PANSS total.

Outcome measuresFocusing on each module described previously, the main objectives of each one and the main procedures and assessments done are detailed:

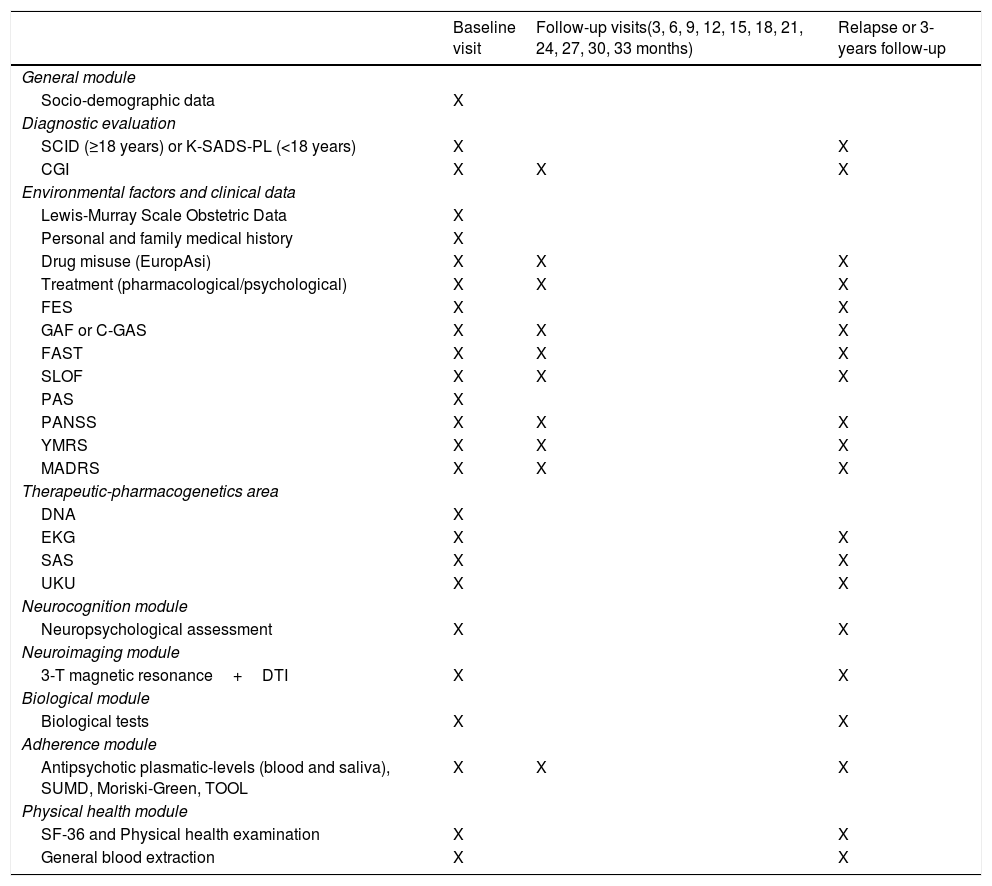

General moduleAll groups participated in this module. At baseline, a complete evaluation (structured interview, clinical scales, family environment, prognostic and premorbid adjustment scales, genetic and analytic) was performed. All scales were administered by expert clinicians, except those that were self-administered. The pharmacological and psychological treatment and Adverse Drug Reactions (ADRs) were also recorded. Clinical, functional and disability scales were administered again at follow-up visits (3, 6, 9, 12, 15, 18, 21, 24, 27, 30, 33, 36 months) or relapse, as appropriate (see Table 1).

Outcome measures, assessment frequency and timings.

| Baseline visit | Follow-up visits(3, 6, 9, 12, 15, 18, 21, 24, 27, 30, 33 months) | Relapse or 3-years follow-up | |

|---|---|---|---|

| General module | |||

| Socio-demographic data | X | ||

| Diagnostic evaluation | |||

| SCID (≥18 years) or K-SADS-PL (<18 years) | X | X | |

| CGI | X | X | X |

| Environmental factors and clinical data | |||

| Lewis-Murray Scale Obstetric Data | X | ||

| Personal and family medical history | X | ||

| Drug misuse (EuropAsi) | X | X | X |

| Treatment (pharmacological/psychological) | X | X | X |

| FES | X | X | |

| GAF or C-GAS | X | X | X |

| FAST | X | X | X |

| SLOF | X | X | X |

| PAS | X | ||

| PANSS | X | X | X |

| YMRS | X | X | X |

| MADRS | X | X | X |

| Therapeutic-pharmacogenetics area | |||

| DNA | X | ||

| EKG | X | X | |

| SAS | X | X | |

| UKU | X | X | |

| Neurocognition module | |||

| Neuropsychological assessment | X | X | |

| Neuroimaging module | |||

| 3-T magnetic resonance+DTI | X | X | |

| Biological module | |||

| Biological tests | X | X | |

| Adherence module | |||

| Antipsychotic plasmatic-levels (blood and saliva), SUMD, Moriski-Green, TOOL | X | X | X |

| Physical health module | |||

| SF-36 and Physical health examination | X | X | |

| General blood extraction | X | X | |

SCID: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV; K-SADS-PL: Kids Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children-Present and Lifetime version; CGI: Clinical Global Impression Scale; EuropASI: the multidimensional assessment tool European Addiction Severity Index; FES: Family Environment Scale; GAF: Global Assessment of Functioning Scale; C-GAS: Children's Global Assessment Scale; FAST: Functional Assessment Staging; SLOF: Short Level of Function Scale; PAS: Premorbid Adjustment Scale; PANSS: Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale; YMRS: Young Mania Rating Scale; MADRS: Montgomery–Asberg Depression Rating Scale; DNA: Genetic sample extraction; EKG: Electrocardiogram; SAS: Simpson–Angus Scale; UKU: Scale of the Udvalg for Kiniske Undersogelser; 3-T: 3 Teslas; DTI: Diffusion Tensor Imaging; SUMD: Scale to Assess Unawareness of Mental Disorder; TOOL: Tolerability and Quality of Life; SF-36: Short Form-36 Health Survey Questionnaire.

The first step in this project was to confirm the diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizophreniform disorder. For this, Spanish validated semi-structured interviews appropriate to the patients’ age (SCID-I and II42,43 and K-SADS45) were used to confirm the diagnosis of schizophrenia according to required DSM-IV criteria.

Demographic, clinical and environmental factorsFollowing the same procedure as in the PEPs Project, a complete personal and family history was performed in a systematic self-devised interview at baseline, including drug history.

In every assessment during the project, information about which prescribed drugs the subject was taking, dosage and the presence of severe ADRs was collected.

Antipsychotic plasmatic levels (as an indirect measure of the patients’ level of pharmacological treatment adherence) were also determined at each visit, being an indirect measure of the patients’ level of pharmacological treatment adherence.

Anthropometric measures, electrocardiogram and menstrual and pregnancy-related information (if applicable) were obtained in every visit with the aim of monitoring physical health indicators.

In women, the age at menarche and the date of last period were registered. Women were asked whether they were pregnant or had used a pregnancy test in the previous month.

Since the inclusion of children and adolescents was allowed in the study, sexual maturity was established by the Tanner scale for subjects younger than eighteen years of age.46

Clinical status and global functioningIn order to get global functional outcome information, four different scales were used:

- 1)

The Clinical Global Impression Scale (CGI-S)47 assesses severity and improvement of global symptomatology. It is particularly helpful for repeated evaluations of global psychopathology.

- 2)

The Functional Assessment Staging Test (FAST)48 evaluates the patient's degree of difficulty in autonomy, work functioning, cognitive functioning, finance, interpersonal relationships and free time functioning. Recently, our group has validated five categories (none, minimal, mild, moderate and severe) representing categories of functional impairment in first-episode of schizophrenia based on meaningful empirical cut-offs for FAST (9, 19, 34, 45 and ≥46), which can help to differentiate and personalize the interventions according to its functional outcome [work under review].

- 3)

The Global Assessment of Functioning Scale (GAF)49 and the Children's Global Assessment Scale (C-GAS),50 which measure the severity of symptoms and the level of functioning, and 4) the Level of Function Scale (SLOF),51 which is a semi-structured interviewer-administered scale containing nine items in four domains, including variables which predict how the disease will progress. It includes variables which predict how the disease will progress.

Assessments of family background and obstetric complications were included; the family background was assessed by the Family Environment Scale,52 a self-report scale which includes ten subscales reflecting the socio-environmental characteristics of families.

Obstetric complications were recorded using the Lewis–Murray Scale of Obstetric Data.53 The evaluator retrospectively rates information on obstetric complications. Lastly, the subjects’ urbanicity was also recorded.

Alcohol and drug useDrug abuse was evaluated in every visit via part of the European adaptation of a multidimensional assessment instrument for drug and alcohol dependence: the multidimensional assessment tool European Addiction Severity Index (EuropAsi).54 At baseline, a systematic register of drug misuse habits was performed.

Clinical assessment scalesSeparating by different areas, the scales used were the following:

Psychotic symptoms

Symptom severity and functional status were assessed using different scales. The validated Spanish version of the Positive and Negative Symptom Scale (PANSS),41,55 which comprises 3 subscales: positive, negative and general. To enhance reliability, the PANSS includes a well-developed anchor system. In addition, validated criteria of schizophrenia remission are based in some of their items.

Affective symptoms

The Spanish validated version of the Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS), designed to assess the maniac symptoms severity,56,57 and the Spanish validated version of the Montgomery–Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS), for depression severity evaluation,58,59 were chosen.

Premorbid adjustment

The Premorbid Adjustment Scale (PAS)60 explores sociability and withdrawal, peer relationships, school achievement, adaptation to school, and ability to establish socio-affective and sexual relationships. The scale considers different age ranges: childhood (up to 11 years), early adolescence (12–15 years), late adolescence (16–18 years), and adulthood (19 years and older). This scale was completed based on information obtained from the patient and parents.

The evaluation of adverse drug reactions (ADRs)

Spontaneous reports of ADRs and a systematic assessment of ADRs were gathered in every visit – except at baseline – using the Scale of the Udvalg for Kiniske Undersogelser (UKU),61 a comprehensive rating scale designed to assess the general side effects of psychotropic drugs, and the Simpson–Angus Scale (SAS),62 oriented to evaluate the extrapyramidal side effects.

Neuroimaging moduleA structural Magnetic Resonance Imaging (sMRI), Functional (resting state) and Diffusion Tension Imaging (DTI-MRI) was performed in all the patients from centers involved in this module. MRI scans were acquired at baseline either at 3-year follow-up visit or at the time the patient presents a relapse. Six different scan machines were used: 1 Siemens Symphony 1.5T, 2 General Electric Signa, 1 Philips Achieva 3T, 1 Philips intera 1.5T and 1 Siemens Magneton Trio 3T. Data were collected from each center and processed centrally at one site. Sequences were acquired in axial orientation for each subject, a T1-weighted 3D gradient echo (voxel size 1mm×1mm×1.5mm) and a T2-weighted Turbo-Spin-Echo (voxel size 1mm×1mm×3.5mm).

In order to be able to pool together volumetric data, multicenter MRI studies required a prior evaluation of compatibility between the different machines used. In the first phase of the study the compatibility of the six different scanners was calculated a priori by repeating the scans of six volunteers at each of the sites. Using a semiautomatic method based on the Talairach atlas, and SPM algorithms for tissue segmentation (multimodal T1 and T2, or T1-only), we obtained volume measurements of the main brain lobes (frontal, parietal, occipital, temporal) and for each tissue type and subject. MRI images were processed using locally developed software incorporating a variety of image processing and quantification tools.

Neurocognition moduleThe neuropsychological battery employed in this study was designed to address different cognitive domains by means of standardized neuropsychological tests that have proven sensibility and specificity. The battery is extensive and covers the areas proposed by the NIMH MATRICS consensus, in addition to verbal memory.63,64 This battery was previously used in the PEPs Project and in the cognitive assessment of this type of patient. All tests were administrated by specialized neuropsychologists.

Neuropsychological assessment in children and adolescents must take into account their different developmental levels. In order to estimate global functioning in the form of IQ, vocabulary and cubes subtests from the WISC-IV65 or WAIS-III66 were used for patients and controls under and over 16 years of age, respectively.

The potentially impaired cognitive domains were assessed with the following instruments:

- ∘

Attention was assessed by means of the Conners’ Continuous Performance Test-II,67 direct order from the Digit Span Subtest of the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-III (WAIS-III)66 in adults or Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children-IV (WISC-IV)65 in children, Stroop test68 and Trail Making Test-part A.69

- ∘

Working memory, by means of the reverse order from the Digit Span Subtest, the Letters and Numbers Subtest of the WAIS-III in adults or WISC-IV in children.65,66

- ∘

Executive functions, by means of the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test,70 and the Trail Making Test-part B.69

- ∘

Verbal fluency, with phonetic and categorical mark, memory and verbal learning, by means of the España-Complutense Verbal Learning Test-TAVEC71 for adults and children-TAVECi.72

- ∘

Social cognition, with the Mayer-Salovey-Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test-MSCEIT included in the MATRICS battery.73,74

- ∘

Analysis of handedness, assessed with the Edinburgh Inventory.75

- ∘

Processing speed, with the Trail Making Test-part A and Stroop test.68,69

The neuropsychological battery was administered at baseline and repeated at the 3 years visit/or at relapse, whichever happened first.

To evaluate the differences between raters, an interrater reliability study was also conducted among different neuropsychologists at each center. Those who failed the first evaluation were re-trained and assessed. The complete methods and the inter-rater reliability results have been described previously in a specific work.76

Adherence moduleThe assessment of adherence has been performed with standardized scales and complemented with various biochemical measurements such as drug concentrations in blood or saliva; The Scale to Assess Unawareness of Mental Disorder (SUMD),77 which is a semi-structured open interview that evaluates global insight, insight into illness and insight into symptoms; the Morisky Green Levine Medication Adherence Scale (MGLS), used for measuring the extent of medication non-adherence,78 and the Tolerability and Quality of Life Questionnaire (TOOL), which evaluates the impact of the adverse effects of antipsychotic drugs on patients.79

Monitoring of antipsychotic concentrations is recommended for all these therapeutic agents that have limited therapeutic ranges and are at high risk for associated severe adverse effects. Antipsychotic drug level for patients taking risperidone, paliperidone olanzapine, quetiapine and aripiprazole has been determined in saliva using ultrahigh performance liquid chromatography combined with high resolution mass spectrometry. During the visit at 3, 6, 12 and 24 months. In addition, the blood levels of antipsychotic drugs were determined for these patients.

Biological moduleThrough biochemical measurements taken at baseline and at 3-years/or relapse after the inclusion in the study, this module focused on conducting an extensive analysis of the biomarkers involved in oxidative stress, inflammatory and anti-inflammatory processes, epigenetics and neurotrophins markers potentially involved in relapses.

Biological samples from patients were collected, prepared, stored and transported according to the general protocols from CIBERSAM. For each patient, 10mL of anticoagulated blood were prepared. Biological determinations have been done in plasma, in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) and in erythrocytes (hemolyzed). Analysis of epigenetic mechanisms have been performed through DNA methylation and microRNA expression analysis. The genotyping of the different genetic polymorphisms in each of the genes (NGF, BDNF, NT3) have been carried out using the Centro Nacional de Genotipado (CeGen) platform.

Physical health moduleTo study physical health parameters, complemented with various biochemical measurements, the Short Form 36 (SF36) Health Survey Questionnaire80 is used at baseline visit and at 3-year follow-up or relapse. The SF36 is a short questionnaire with 36 items which measure eight multi-item variables: physical functioning, social functioning, role limitations due to physical problems, role limitations due to emotional problems, mental health, energy and vitality, pain, and general perception of health. For each variable item scores are coded, summed, and transformed on to a scale from 0 (worst possible health state measured by the questionnaire) to 100 (best possible health state).

Data processingData collection has been carried out through a computerized system (GRIDSAM) that ensures centralized data collection from all centers participating in the 2EPs Project. Its conception follows the PsyGrid philosophy, defining a Service-Oriented Architecture (SOA) on which several web applications are built that interact with a central database. The GRIDSAM allows for the capture of data by means of a multi-grid computerized system, which not only integrates all the available information but also facilitates more efficient data exploitation and management.

DiscussionThe main purpose of the present article is to report the rationale, the design, the developmental processes and the assessment adopted in the 2EPs Project. This project has the principal objective of evaluating the clinical course and functional outcomes – with neuropsychological assessments, biological, neuroanatomical, genetic adherence and physical health monitoring – over three years of a sample of persons with a FES in remission in order to compare two subgroups of patients; those who present a second episode and those who do not experience relapse.

In first-episode populations, there is ample evidence that an early intervention is efficient. In this way, the design, development and validation of active relapse prevention programs are the first step to ensure a complete and correct approach, guaranteeing individualized and personalized treatments.6,81 Thus, a comprehensive recovery-oriented, evidence-based intervention to promote quality of life, participation in work and school, clinical remission and functional recovery needs to be developed.82,83 Given this need, numerous programs have emerged with the main objective of preventing second episodes and subsequent relapses. One of them was the project “Preventing Relapse Oral Antipsychotics Compared to Injectables eValuating Efficacy” (PROACTIVE), a 30-month relapse prevention study to compare relapses among patients receiving either long-acting injectable or oral second-generation antipsychotics.84 Another big project has been the “European First Episode Schizophrenia Trial” (EUFEST), which was designed to study and to compare the clinical effectiveness of first and second generation antipsychotics in first-episode patients.85 Last but not least, the “Recovery After an Initial Schizophrenia Episode-Early Treatment Program” (RAISE-ETP), which aimed to develop, test, and implement person-centered, integrated treatment approaches for FEP to promote symptomatic and functional recovery.82

After a thorough characterization of first episodes of schizophrenia in the framework of the PEPs Project,37 the 2EPs Project arose to characterize patients at remission from a first episodes in an exhaustive, novel and multimodal way to contribute toward the development of a predictive model of relapse. The only means of preventing relapses is to undertake longitudinal studies in early phases like the PEPs and 2EPs Projects.

Similar to the PEPs Project, in this naturalistic study, the selection of the sample tried to be as close as possible to the “real-world” patients with a FES in remission. For example, this naturalistic approach justifies the inclusion of infantile-juvenile patients (age at onset under 18 years) have been included which will allow the pattern of early onset to be studied in addition to its relationship with this pathology's risk factors when the appearance of the first-episode is very early. Another example is the inclusion of patients with substance use disorders. Due to the fact that people with first-episode schizophrenia frequently have comorbid substance use, usually involving alcohol and cannabis, which put a population particularly at risk of prolonged psychosis and psychotic relapses,86 it was of special interest to include those patients with consumption of substances. The naturalistic design was thus a key factor to assess the applicability of the results to daily clinical practice. The fact that the sample recruited in this project includes FES patients allows us to study the onset of the disease at early stages and limiting confounding variables, such as a long evolution or the long-term effects of antipsychotic medication. It is in the early stages of the disease when the most useful strategies for helping patients including adherence to treatment to understand the benefits of the medication and, especially, to administer them at the appropriate doses, should be implemented.

In our sample, 44% of patients with a FES in clinical remission presented a relapse during the three years of follow-up after the baseline visit. This percentage is in accordance with the well demonstrated data that relapse rates are higher in the critical period after the onset of the illness (until two years) than in other periods, ranging from 30% to 60%.10

It has been well demonstrated that adherence to treatment is a major determinant of treatment success while the lack of it is a global health problem of alarming magnitude, particularly in long-term treatments for chronic conditions.87-88 In developed countries, adherence in patients44 with chronic diseases averages only 50%.76,82,84,85 Poor adherence attenuates optimum clinical benefits and therefore reduces the overall effectiveness of health systems.

In this line, the 2EPs Project may also provide the identification of genetic, neuroimaging, biological and clinical variables and their role in treatment adherence, together with the application of various techniques to determine antipsychotic levels, which allow the validity of new biochemical methods that can help to identify therapeutic compliance to be tested. In the same way, the implementation of new non-invasive strategies for antipsychotic analysis, such as detection in saliva, will reduce the burden associated with transferring to health services to monitor adherence. Furthermore, these new techniques will permit the personalization of patients’ clinical therapies by adjusting the dose.

The proper coordination between centers allowed for the integration of information from the different modules in order to interrelate the hypotheses of the different sub-studies (e.g. at the clinical and neuroimaging, clinical and physical health, clinical and neurocognition levels, adherence to the treatment). This global perspective aimed at developing an evidence-based strategy that provides clinicians with useful resources for intervention in a first-episode with a view to consequent prevention of the second episode as an essential added value to the proposal of clinical intervention guides.

Notwithstanding, some limitations could be considered. One of the difficulties common to all longitudinal studies is the loss of subjects included in the study. To reduce this loss personal contact was established with patients and their families when arranging visits and outpatient follow-up was conducted by the psychiatrists participating in the study. Similarly, compliance in all visits may be lower than expected since the frequency (every three months) and the follow-up period (three years) are high. Again, attempts were made to reduce this loss through personal contact with patients and their caregivers. Moreover, an inherent limitation of clinical and neuropsychological evaluation procedures lies in the inter-observer differences, for which the usual procedures are applied to reduce this type of possible bias. First, semi-structured clinical interviews were included, and second, regular meetings were held to reduce the differences between the neuropsychological evaluators of the different research groups. Lastly, due to the naturalistic design, drug treatment was not controlled. The study participants maintained their usual treatment. Although this may limit the evaluation of some variables, this method eases the recruitment and it also gives a global picture of the usual treatment and outcome in these patients.

Nevertheless, besides these limitations, one strong point of the 2EPs Project (as well as of the PEPs Project) is the broad neuropsychological battery used. Compared to previous first-episode of psychosis projects such as EUFEST, PROACTIVE or RAISE-ETP, which used brief assessment battery or did not have any cognitive data collected,76,82,84,85 the neuropsychological battery employed in this study was extensive and covered the areas proposed by the NIMH MATRICS consensus.63 Moreover, it is worth highlighting that, in line with and as a continuation of the PEPs Project, this is the largest collaborative project ever undertaken in our country, which increases the chances of finding relevant and applicable results for the daily management of psychotic patients.

Thus, a special need in FES populations is to demonstrate the evidence for efficiency in the prevention of relapses, and to ensure that high-quality care is provided in research settings as well as in routine practice. Pragmatic research is being adopted to enhance the generalization of findings to clinical practice and to aid in the recruitment of patient samples that are more broadly representative of community mental health practices.82,84,89,90 The extent to which each informs the other offers the potential for future gains in the delivery of care for people with FES.

In conclusion, after the effective characterization of FES (goals achieved thanks to the PEPs Project) and the study of the variables that can predict the appearance of a relapse (clinical, biological, neuroanatomical, genetic, treatment compilation and physical health monitoring), which was the main purpose of the 2EPs Project, the validation of these interventions in this population taking into account all these variables would validate the clinical guidelines, based on evidence, to define good clinical practice.

FundingThis study is coordinated by Dr. Bernardo and is part of the coordinated-multicentre project, funded by the Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad, Instituto de Salud Carlos III – Fondo Europeo de Desarrollo Regional, Unión Europea. Una manera de hacer Europa; Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red de salud Mental, CIBERSAM, by the CERCA Program/Generalitat de Catalunya And Secretaria d’Universitats i Recerca del Departament d’Economia I Coneixement (2017SGR1355). Departament de Salut de la Generalitat de Catalunya, en la convocatoria corresponent a l’any 2017 de concessió de subvencions del Pla Estratègic de Recerca i Innovació en Salut (PERIS) 2016-2020, modalitat Projectes de recerca orientats a l’atenció primària, amb el codi d’expedient SLT006/17/00345. Dr. Bernardo is also grateful for the support of the Institut de Neurociències, Universitat de Barcelona.

Conflicts of interestDr. Bernardo has been a consultant for, received grant/research support and honoraria from, and been on the speakers/advisory board of ABBiotics, Adamed, Angelini, Casen Recordati, Janssen-Cilag, Lundbeck, Otsuka, Rovi, Menarini and Takeda.

The rest of the authors report no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest.

We are grateful to all participants.

We would also like to thank the Carlos III Healthcare Institute, the Spanish Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities, the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF/FEDER) (PI080208, PI11/00325 and PI14/00612); CIBERSAM; CERCA Program; Catalan Government, the Secretariat of Universities and Research of the Department of Enterprise and Knowledge (2017SGR1355); PERIS (SLT006/17/00345), and Institut de Neurociències, Universitat de Barcelona.

Ana González-Pintoaa, Daniel Bergéab, Antonio Loboac, Eduardo J. Aguilarad, Judith Usallae, Iluminada Corripioaf, Julio Bobesag, Roberto Rodríguez-Jiménezah, Salvador Sarróai, Fernando Contrerasaj, Ángela Ibáñezak, Miguel Gutiérrezal, Juan Antonio Micóam

aa Department of Psychiatry, Araba University Hospital, Bioaraba Research Institute, Department of Neurociences, University of the Basque Country, CIBERSAM, Vitoria, Spain.

ab Department of Neurosciences and Psychiatry, Hospital del Mar Medical Research Institute (IMIM), Barcelona, Spain.

ac Department of Medicine and Psychiatry. Universidad de Zaragoza. Instituto de Investigación Aragón, CIBERSAM, Zaragoza, Spain.

ad Department of Psychiatry, Hospital Clínico Universitario de Valencia, School of Medicine, Universidad de Valencia, CIBERSAM, Valencia, Spain.

ae Parc Sanitari Sant Joan de Déu, Institut de Recerca Sant Joan de Déu, SantBoi de Llobregat; Fundació Sant Joan de Déu, Institut de Recerca Sant Joan de Déu, Esplugues de Llobregat, Barcelona, Spain.

af Department of Psychiatry, Biomedical Research Institute Sant Pau (IIB-SANT PAU), Santa Creu and Sant Pau Hospital; Autonomous University of Barcelona (UAB), CIBERSAM, Barcelona, Spain.

ag Área de Psiquiatría, Universidad de Oviedo, Servicio de Salud del Principado de Asturias, Instituto de Neurociencias del Principado de Asturias (INEUROPA), CIBERSAM, Oviedo, Asturias, Spain.

ah Departamento de Psiquiatría, Instituto de Investigación Sanitaria Hospital 12 de Octubre (Imas12), CogPsy-Group, Universidad Complutense de Madrid (UCM), CIBERSAM, Madrid, Spain.

ai FIDMAG Research Foundation Germanes Hospitalàries, CIBERSAM, Barcelona, Spain.

aj Psychiatry Department, Bellvitge University Hospital-IDIBELL, Barcelona, Spain; Department of Clinical Sciences, School of Medicine, University of Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain.

ak Departamento de Psiquiatría, Hospital Ramon y Cajal, Universidad de Alcalá, IRYCIS, CIBERSAM, Madrid, Spain.

al Department of Psychiatry, Hospital Santiago Apóstol, University of the Basque Country, CIBERSAM, Vitoria, Spain.

am Grupo de Investigación en Neuropsicofarmacología y Psicobiología, Departamento de Neurociencias, Universidad de Cádiz, Instituto de Investigación e Innovación en Ciencias Biomédicas de Cádiz, INiBICA, Hospital Universitario Puerta del Mar, CIBERSAM, Cádiz, Spain.