Demographic aging trends will have consequences concerning the general population, the composition of the workforce and the shortage of some skills in the near future. The aim of this study is to explore what the HRM practices are that workers identify in their organizations, as well as the importance they attach to each of these practices, according to their age.

A survey was carried out on 528 workers from various companies, to this end. This study showed that the dimensions of “Training; Rewards, Recognition and Participation”; and “Performance Evaluation” are the HRM practices most valued by workers of all ages. The dimension of “Flexible Work Practices” shows the lowest average score for older workers. “Job Security” is the practice that all workers, but particularly the older ones, perceive as being less present in the organization.

Workers, in general, value HRM practices more than they perceive them to exist in organizations.

Despite the empirical evidence of the importance that Human Resource Management (HRM) practices have in attracting, employing and retaining workers, little is known about the influence of age on HRM practices and their results in terms of workers (Kooij, De Lange, Jansen, & Dikkers, 2008).

The workers’ needs and the utility of HRM practices change with age (Kooij, Jansen, Dikkers, & De Lange, 2010). Besides that, HRM practices based on age have, in general, an influence on how people of different ages behave in the organizations (Combs, Liu, Hall, & Ketchen, 2006; Schalk et al., 2010). In this sense, this study is intended to identify which organizational HRM practices workers are most aware of, as well as to try to understand the importance they attach to each of these practices and, accordingly, assess whether the practices that companies follow are in accordance with the needs and the wishes of the workers.

2Aging2.1Aging populationEveryone gets older and the population is growing older. This is a fact, which confronts us daily and is often perceived as a threat to the future of our society. In part, this concern is related with the inability of society to adapt to social, organizational and mental developments (Rosa, 2012). The current growth rate of the elderly population is one of the most salient features of recent demographic trends. Many countries are struggling with changing demographics that have consequences at the population level and affect the composition of the workforce and labor skill shortages (Armstrong-Stassen, 2008; Armstrong-Stassen & Schlosser, 2011; Schalk et al., 2010). The demographic transition associated with declining levels of fertility and mortality has been causing unprecedented changes in the age structure of the population worldwide, which means that more than half (55 percent) of the world's governments consider the aging population of their countries as a major concern (UN, 2013).

The Portuguese case is one of the clearest among European countries, since the latest census shows two main developments: (1) the number of young people is declining and (2) the number of older people is increasing, i.e., the phenomenon is one of double aging (INE, 2011). The aging index, the number of elderly (65 and over) per 100 young people (0–14 years), in 1960 was 27.0%, in 2012 it was 129.4% and it is expected that in 2060 there will be 307 seniors for every 100 young people (INE, 2014; Pordata, 2014). Therefore, the expected old-age dependency ratio (this indicator is defined as the number of people aged 65 and over, expressed as a percentage of the number of people aged between 15 and 64) in Portugal in 2010, was 26.70%, and in 2050 it is expected to be 55.62% (Eurostat, 2014). These data demonstrate the country's demographic profile, characterized by an aging population that results from the decrease in birth rates and the increase in the number of elderly people. This may explain the negative index of the renewal of generations. Consequently, the demographic changes that are now confronting us will also have, in the near future, a great impact on the composition of the workforce.

Despite the differences between countries, most are experiencing demographic changes that have consequences regarding the active population and the composition of the workforce (Schalk et al., 2010; Winkelmaan-Gleed, 2011). In this context, the concerns of governments and organizations (governmental, nongovernmental and intergovernmental) about the need to increase the participation of older workers in the labor market (Streb, Voelpel, & Leibold, 2008) should not be ignored. For example, the European Union has set governments, social partners and organizations the objective of increasing the employment rate of older workers, as well as providing access to the skills development that will enable them to grow old while maintaining their health, motivation and capabilities (Naegele & Walker, 2006).

2.2Aging workforceAn aging population means an aging workforce that may lead to a conflict of interests between younger and older workers. In the next few decades, older workers will be forced to play a prominent role in the workforce (Armstrong-Stassen & Schlosser, 2011), in order to facilitate economic growth (Posthuma & Campion, 2009). Burke and Ng (2006) and Koçak (2011) reinforce this idea by claiming that both the nature of the globalizing world economy, as well as the aging of the workforce are recognized as two of the most important factors affecting the reality of organizations in many industrialized countries. Moreover, they state that this situation will probably not change in the near future. An aging society faces many challenges involving issues such as: the economy, society, policies and culture. These issues emphasize the impact of aging on national productivity, economic growth and global competitiveness, considering that the permanence and contribution of older workers in the labor market affect not only the economic and social well-being of the workers themselves, but also the standard of living of current and future generations (Arnone, 2006).

Despite the declared need and desirability of retaining older workers in the workforce, the older, opposite trend of the decreasing participation of these people in organizations (Hult & Stattin, 2009; Ranzijn, 2004; Roberts, 2006), may still often be observed. Companies continue to seek and hire young people, instead of exploiting the advantage of the older workers’ knowledge (Homberg & Bui, 2013). Various authors and institutions have argued that it is necessary to encourage older workers to remain in the labor force and to contribute significantly to the organization as a strategy to reverse this trend (Armstrong-Stassen, 2008; Hedge, 2008). The European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions (2006) calls the attention of governments to the need of encouraging older workers to continue working for as long as possible and also of employers, as they need to retain and nurture their older workers. In this sense, managers must share a common vision about the most appropriate age structure for their organization as well as define and adopt policies and Human Resource Management practices to help them achieve this aim.

3Human resource management and age management in organizationsIn the uncertain and turbulent environment in which we live, it is crucial to protect and develop human resources, which are considered a strategic and unparalleled asset for creating sustainable competitive advantages (Boxall & Purcell, 2003; Paauwe & Boselie, 2003). In addition, Human Resource Management has been recognized as a source of competitive advantage (Barney, 1991). In that sense, Human Resource Management has undergone profound changes according to the needs of companies to enhance their competitive ability to face global markets (Lacombe & Tonelli, 2001). Therefore, the economic changes highlight the importance of technical and financial resources coupled with the role of workers, in order to achieve success and stability in a changing market. The transition from the old economy, dominated by physical tasks and based on mass production, to the new economy, characterized by knowledge-intensive organizations and networks, has emphasized the importance of intangible assets (Boselie, 2010).

HRM practices are tools that assist in the management and guidance of attitudes and behaviors but also the performance of human resources in order to achieve organizational goals. There are several studies that give us an account of this influence on behavior and performance (Hiltrop, 1996; Huselid, 1995). Organizations should invest time and money on the development of HRM practices that help to boost competitiveness and promote the growth and commitment of employees. The meta-analyses of Combs et al. (2006), demonstrate that human resources should be strategically managed and that some practices are crucial to improve organizational performance.

Most research on HRM practices assumes that these practices influence all employees in the same way (Lepak & Snell, 1999). According to Hayton and Kelley (2006) and Maison and Barrett (2006), HRM practices influence organizational performance and have a positive impact on company performance, even if these practices are informal. More recently, different authors have questioned this point of view and argue that individuals experience HRM practices differently and that different groups of workers do not respond to these practices in the same way (Kinnie, Hutchinson, Purcell, Rayton, & Swart, 2005). However, human resource management practices, in general, influence the way in which people of different ages behave in organizations (Combs et al., 2006; Schalk et al., 2010). In the future, probably companies will have to deal not only with an aging workforce, but also with other changes in its composition. These changes will make it even more important to use the abilities of the growing number of older assets which, in turn, will have to become employable and productive to compensate for the declining number of young people (Backes-Gellner & Veen, 2009). In this sense, an age management approach may become an effective mechanism for promoting age diversity in organizations (Walker, 2005).

Many employers are aware of the issues related to the aging of the workforce but only a few of them have taken any kind of action to address them (Armstrong-Stassen, 2008). To illustrate this fact, the author mentions a study conducted by Manpower in 2007, where over 28,000 employers in 25 countries were interviewed and it concluded that only 21% of them developed strategies in order to retain their older workers. Moreover, a clarification of the attitudes and motives of employees of different ages may contribute to a better definition of organizational policies and practices. As Walker (2005) stresses, HRM practices may be of interest to all workers, particularly to older workers, since they may encourage them to stay active and involved in the workforce (Barnes-Farrell & Matthews, 2007). Managers have been encouraged to manage their employees according to their needs and requirements, i.e., make a tailored management for different ages (James, McKechnie, & Swanberg, 2011). The challenge for the organizations goes beyond aging, yet it is also important to know how to deal with the decrease in the workforce and the increase in age diversity.

The term “age management” refers specifically to the different dimensions through which human resources are managed within organizations, with an explicit focus on aging and also, more generally, to the overall management of an aging working population through public policies or collective bargaining. “Good practices in age management” are defined as measures to combat the barriers of age, to promote the diversity of age and that create an environment where individuals are able to achieve their potential without being disadvantaged by their age (Walker, 2005). With regard to good practices related to age management in organizations, Casey, Metcalf, and Lakey (1993) defined five key dimensions: recruitment and exit, training, development and promotion, flexible working practices, ergonomics and design functions and finally, changing attitudes toward older workers. In turn, Armstrong-Stassen (2008) identifies seven human resource strategies and their representative human resource practices. These strategies are: flexible work options, job design, mature employee training, manager training, performance evaluation, compensation and recognition and, respect. However, the strategies of respect and recognition are identified by older workers as the most influential on their decision to stay in the organization. According to Walker (2005) these strategies promote awareness of social justice in the labor market, which help create teams with heterogeneous or complementary experiences and perspectives, the transmission of skills and know-how between generations and, finally, the motivation of older workers.

The majority of the research conducted so far has been to understand why older workers leave their active working life, while the retaining factors have been little discussed. There is little data about the practices that encourage older workers to remain active (Shacklock, Fulops, & Hort, 2007), likewise there is little information related to how specific and relevant practices should be developed and implemented for older workers (Hedge, Borman, & Lammlein, 2006). Armstrong-Stassen (2008) states that there are few articles that report findings of empirical studies in which human resource managers have been questioned about the practices targeted for older workers. The author stresses that the availability of HRMP oriented to the wishes and needs of older workers can be seen as a sign to those whose contributions are valued by the organizations and therefore encourage them to remain in the organization (Armstrong-Stassen, 2008).

For all these reasons it seems important to study if and how Portuguese organizations establish a human resource management policy that considers the age factor. In this regard, and considering the demographic, social and economic changes that have occurred, we believe that the study of the perception and importance attached to HRM practices by workers is undoubtedly crucial for managers to undertake appropriate management of the age pyramid in their organizations.

4Objectives of the studyBased on the assumption that HRM practices based on age have, in general, an influence on the way people of different ages behave in organizations, this study aims to evaluate the perception that workers from different ages have about what the effective HRMPs are in their organizations and, also discover the importance that workers attach to each of these practices.

For this purpose, an exploratory study, whose main goal was to assess which practices the workers are most aware of, and which they value the most, was conducted.

5Methodology5.1ParticipantsMost of the participants are: female (60.9%), aged between 25 and 34 years (37.2%), attended higher education (52.7%), full-time workers (94.0%), in the industrial sector (47.9%), have responsibilities as an employee or staff member (38.8%) or technicians and intermediate level professionals (33.3), worked for between 6 and 10 years (18.3%), and they have been in the organization for between 2 and 5 years (25.3%) and, with a tenure of between 2 and 5 years (33.0%).

5.2ProcedureThe study took place at an individual level and the approach was quantitative, through the use of a survey. After contacting the companies that participated in a previous study, the Human Resource Managers were sent an email where the purpose of the study was explained, the confidentiality of the information requested assured and the link through which they could access the questionnaire provided. Subsequently, the Human Resource Managers requested the company's employees to fill out the questionnaire. Data collection was made through the application of the survey developed on Qualtrics software and 528 responses were validated. The statistical analysis of the data was performed with SPSS version 21.0 software.

5.3QuestionnaireBesides the usual socio-demographic information, the questionnaire comprises 48 items related to HRM practices: “Recruitment and Job Security”, “Training and Progression”, “Job Design”, “Performance Evaluation”, “Rewards, Recognition and Participation”, and finally, “Flexible Work Practices”. The development of the items was based on the scales proposed by Sun, Aryee, and Law (2007) and Armstrong-Stassen (2008) regarding HRM practices. The participants are first asked to identify the level of agreement concerning what they think happens in their organization (“What happens in the organization where I work …”) for all the items and, secondly, to identify the degree of importance they attached to this practice (“To what extent it is important to me …”). For each item, participants should answer on a five-point scale, ranging from “very poor” to “very good”.

6Analysis and discussion of results6.1Descriptive analysisAs a first step, a descriptive analysis of the items comprising the questionnaire concerning “What happens in the organization where I work” and “To what extent it is important to me” was conducted.

Regarding “What happens in the organization where I work”, the variables that respondents identify as the most effective HRMP in their organizations are those related to Training and Progression, including the items “There are training programs for newly hired employees, in order to provide them with the skills they need to perform their function” (3.77) and “All employees have access to training programs regardless of their age” (3.77). These results may result from the fact that training constitutes one of the key obligations to be fulfilled by employers and is enshrined in the Labor Code in Portugal. Another aspect that most respondents are aware of in their organizations is the Evaluation of Performance and, in particular, the item “Performance is evaluated” (3.96). Performance evaluation is a tool for assessing and measuring the employee's performance and verifying whether it corresponds to the objectives set by the organization. Through performance evaluation the strengths and weaknesses of organizations may be analyzed and ways to improve performance and contribute to the employees’ profitability is defined, as well as reaching a better understanding of organizational processes and structure. Therefore, this is one of the most effective practices in organizations, both formally and informally. Moreover, according to the average of the respondents’ answers (3.27 on a scale of zero to five points), this is a practice that has consequences and workers are clearly aware of it.

Items that have lower values are mainly related to the variable of Flexible Working Practices and among these we highlight the item “Options are provided for employees to work from home”, with a mean of 2.25 on a five-point scale. According to Ferreira (1999), the practices of flexibility vary between different organizations and there are companies that do not have a policy or institutionalized practice but still exercise it informally with specific groups of workers and depending on situational needs. These practices are related to the technology, science, and telecommunication areas, since they are the sectors where these practices are more widespread and at different hierarchical levels of the organization in addition, they are considered as essential to the development of the business. In contrast, organizations that do not adopt flexible working practices are those that are focused on reducing costs, due to the nature of the business and the needs of the market. In our sample, approximately half of the respondents (47.9%) work in the industrial sector and most of them are staff members (38.8%) or intermediate level technicians and professionals (33.3%), i.e., one of the sectors and functions that are mentioned in the literature as being where less flexible working practices are applied. Another item that also shows a low score is “Promotion is based on seniority”, with a mean value of 2.30. In part, it seems that these results are due to the fact that the majority of respondents have been in the workforce for between 6 and 10 years (18.3%), have been in the organization (25.3%) and function (33.0%) between 2 and 5 years. This means that many workers may not have had the opportunity to progress within the organization yet.

The items about which individuals have a more consensual opinion are the items “Considerable importance is attributed to the selection process” (.929) and “The job description is updated” (.930), which may mean that companies are trying to hire workers with the right profile. In turn, the item that registers a higher standard deviation is “Employees receive bonuses based on the results of the organization.” This heterogeneity of response may be due to the fact that the respondents come from a diverse set of companies, particularly regarding the sector of activity, size of the organization and also the type of function that the workers themselves play. Findings suggest that medium and large organizations tend to reward employees in accordance with the results achieved, mainly at the medium and higher hierarchical levels.

Concerning “To what extent it is important to me”, the variables identified as most important to respondents are those related to “Rewards, Recognition and Participation”, in particular the item “All employees are treated with respect by others in the organization” (4.19), and the variable “Recruitment and Job Security”, in particular, the item “Employees’ potential is valued in the long term” (4.16). This finding can be confirmed in the literature about Perceived Organizational Support. According to this theory, the perceived organizational support is related to the degree in which employees believe that their organization values their contributions and cares about their well-being and socio-emotional needs (Rohades & Eisenberg, 2002). Rhoades and Eisenberger add that “Being valued by the organization can yield such benefits as approval and respect, pay and promotion, and access to information and other forms of aid needed to better carry out one's job. The norm of reciprocity allows employees and employers to reconcile these distinctive orientations” (Rhoades & Eisenberger, 2002:698).

The variable “Flexible Work Practices” seems to be the least important to the respondents (2.97), as well as the one they are less aware of. The item “Appreciation is shown for a job well done” (.757), included in the “Rewards, Recognition and Participation” variable, is the one that shows the greatest consensus. The item that records the lowest consensus is “Promotion is based on seniority,” (1.141) for the variable “Training and Progression”, probably for the same reasons outlined previously.

Finally, results suggest that the average values related to “To what extent it is important to me” are always higher than those for “What happens in the organization where I work.” In other words, we can say that the score for all items “To what extent it is important to me” is superior to what the employees perceive as existing in their organizations.

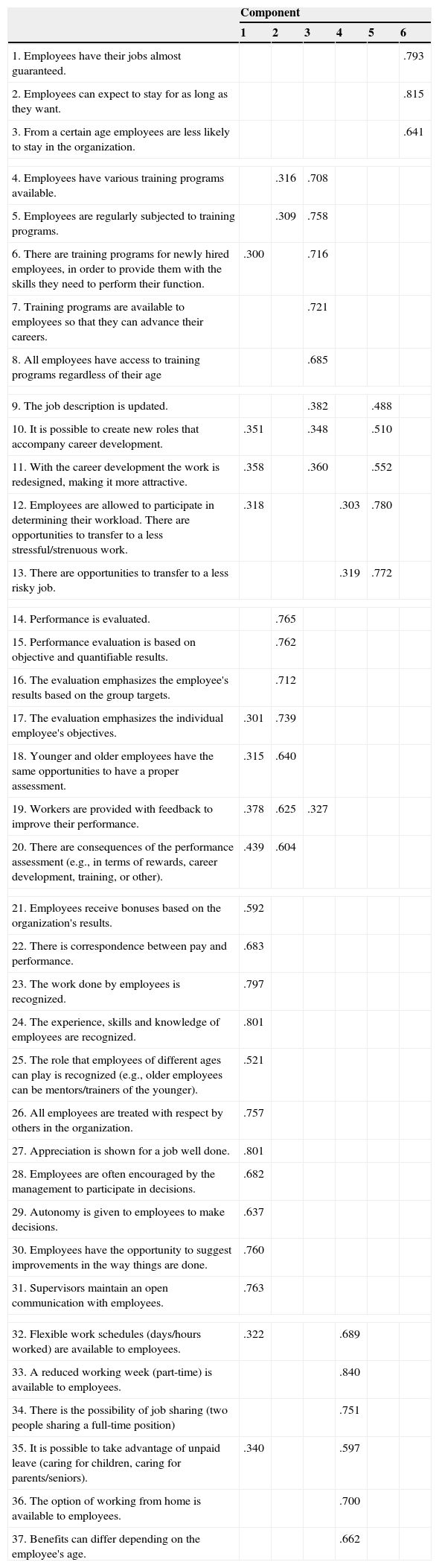

6.2Exploratory factor analysesAn Exploratory Factor Analysis of the items in the study concerning “To what extent it is important to me” was carried out to validate the structure of the questionnaire. The analysis of the internal consistency obtained led to the exclusion of some items, which significantly improved the reliability of the scale. The 38 items retained in the factor analysis yielded a value of 0.947 for the KMO and a p<0.001 associated with the Bartlett test. A Principal Components Analysis was performed for the extraction of the axes and the Cattell scree plot was used to determine the number of axes to retain. The six components retained explain 65.7% of the total variance. After a Varimax rotation, the factor structure obtained shows that Factor 1 summarizes the items on the “Rewards, Recognition and Participation”, Factor 2 is related to “Performance Evaluation”, Factor 3 concentrates information on “Training”, Factor 4 focuses on “Flexible Working Practices”, Factor 5 relates to “Job Design” and Factor 6 with “Job Security”, as can be seen in Table 1.

Factorial matrix obtained after Varimax rotation of the items selected after exploratory factor analysis.a

| Component | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

| 1. Employees have their jobs almost guaranteed. | .793 | |||||

| 2. Employees can expect to stay for as long as they want. | .815 | |||||

| 3. From a certain age employees are less likely to stay in the organization. | .641 | |||||

| 4. Employees have various training programs available. | .316 | .708 | ||||

| 5. Employees are regularly subjected to training programs. | .309 | .758 | ||||

| 6. There are training programs for newly hired employees, in order to provide them with the skills they need to perform their function. | .300 | .716 | ||||

| 7. Training programs are available to employees so that they can advance their careers. | .721 | |||||

| 8. All employees have access to training programs regardless of their age | .685 | |||||

| 9. The job description is updated. | .382 | .488 | ||||

| 10. It is possible to create new roles that accompany career development. | .351 | .348 | .510 | |||

| 11. With the career development the work is redesigned, making it more attractive. | .358 | .360 | .552 | |||

| 12. Employees are allowed to participate in determining their workload. There are opportunities to transfer to a less stressful/strenuous work. | .318 | .303 | .780 | |||

| 13. There are opportunities to transfer to a less risky job. | .319 | .772 | ||||

| 14. Performance is evaluated. | .765 | |||||

| 15. Performance evaluation is based on objective and quantifiable results. | .762 | |||||

| 16. The evaluation emphasizes the employee's results based on the group targets. | .712 | |||||

| 17. The evaluation emphasizes the individual employee's objectives. | .301 | .739 | ||||

| 18. Younger and older employees have the same opportunities to have a proper assessment. | .315 | .640 | ||||

| 19. Workers are provided with feedback to improve their performance. | .378 | .625 | .327 | |||

| 20. There are consequences of the performance assessment (e.g., in terms of rewards, career development, training, or other). | .439 | .604 | ||||

| 21. Employees receive bonuses based on the organization's results. | .592 | |||||

| 22. There is correspondence between pay and performance. | .683 | |||||

| 23. The work done by employees is recognized. | .797 | |||||

| 24. The experience, skills and knowledge of employees are recognized. | .801 | |||||

| 25. The role that employees of different ages can play is recognized (e.g., older employees can be mentors/trainers of the younger). | .521 | |||||

| 26. All employees are treated with respect by others in the organization. | .757 | |||||

| 27. Appreciation is shown for a job well done. | .801 | |||||

| 28. Employees are often encouraged by the management to participate in decisions. | .682 | |||||

| 29. Autonomy is given to employees to make decisions. | .637 | |||||

| 30. Employees have the opportunity to suggest improvements in the way things are done. | .760 | |||||

| 31. Supervisors maintain an open communication with employees. | .763 | |||||

| 32. Flexible work schedules (days/hours worked) are available to employees. | .322 | .689 | ||||

| 33. A reduced working week (part-time) is available to employees. | .840 | |||||

| 34. There is the possibility of job sharing (two people sharing a full-time position) | .751 | |||||

| 35. It is possible to take advantage of unpaid leave (caring for children, caring for parents/seniors). | .340 | .597 | ||||

| 36. The option of working from home is available to employees. | .700 | |||||

| 37. Benefits can differ depending on the employee's age. | .662 | |||||

Extraction method: principal component analysis. Rotation method: Varimax with Kaiser normalization.

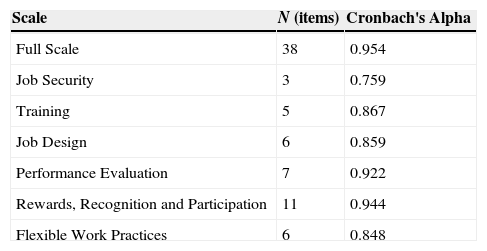

As a measure of internal consistency, Cronbach's alpha was used (Table 2), yielding satisfactory levels ranging from 0.759 (Job Security) and 0.954 (Full Scale).

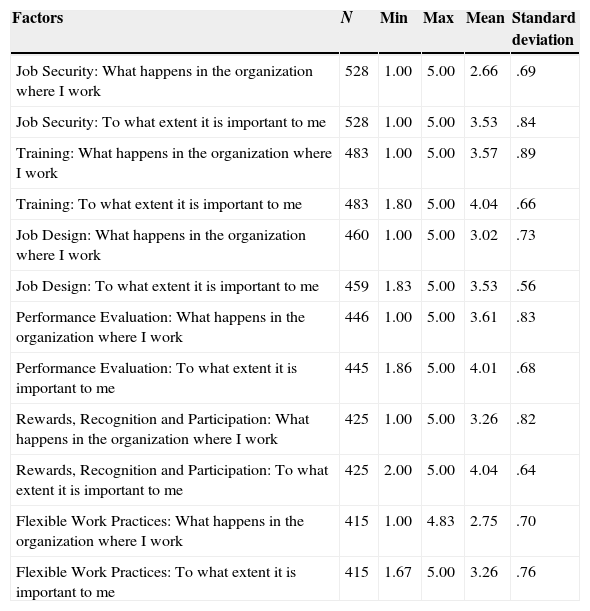

The scores observed for each dimension were calculated. The scores were weighted by the number of items that integrated each dimension to ensure that the results were comparable. Thus, a minimum value of 1 and a maximum value of 5 were assumed. Table 3 shows the basic descriptive statistics for each of the dimensions obtained for the items on the “What happens in the organization where I work” and “To what extent it is important to me”.

Basic descriptive statistics for weighted scores.

| Factors | N | Min | Max | Mean | Standard deviation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Job Security: What happens in the organization where I work | 528 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 2.66 | .69 |

| Job Security: To what extent it is important to me | 528 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 3.53 | .84 |

| Training: What happens in the organization where I work | 483 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 3.57 | .89 |

| Training: To what extent it is important to me | 483 | 1.80 | 5.00 | 4.04 | .66 |

| Job Design: What happens in the organization where I work | 460 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 3.02 | .73 |

| Job Design: To what extent it is important to me | 459 | 1.83 | 5.00 | 3.53 | .56 |

| Performance Evaluation: What happens in the organization where I work | 446 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 3.61 | .83 |

| Performance Evaluation: To what extent it is important to me | 445 | 1.86 | 5.00 | 4.01 | .68 |

| Rewards, Recognition and Participation: What happens in the organization where I work | 425 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 3.26 | .82 |

| Rewards, Recognition and Participation: To what extent it is important to me | 425 | 2.00 | 5.00 | 4.04 | .64 |

| Flexible Work Practices: What happens in the organization where I work | 415 | 1.00 | 4.83 | 2.75 | .70 |

| Flexible Work Practices: To what extent it is important to me | 415 | 1.67 | 5.00 | 3.26 | .76 |

Comparing the scores on items related to the perception that workers have about “What happens in the organization where I work”, with the items “To what extent it is important to me”, which was intended to measure the degree of importance that the practice described has for them, it was found that the scores for all the dimensions of the second scale are always higher. In general, it can be seen that workers have a lower perception of the HRM practices in their organizations while, simultaneously, giving them a greater importance.

HRM practices play an important role in organizational commitment and can strongly impact on maintaining an individual at work until the end of his/her working life, especially for older employees (Schalk, 2007). Besides this, HRMs have an important role in the perception of employability, which makes it critical that organizations formalize their different human resource management practices. In this sense, and according to Bowen and Ostroff (2004), HRMs should communicate, clearly and consistently, what behavior they consider appropriate to their workers. Workers should know and understand the different policies, practices and messages that are sent by the HRMs. This visibility and comprehension can contribute to the implementation of HRM practices. Moreover, their influence on the attributes of workers will lead to the achievement of the desired outcomes at the organizational level, particularly in terms of productivity, financial performance, competitive advantage and innovative behavior (Bowen & Ostroff, 2004). Finally, these findings support our belief that, and according to Combs et al. (2006) and Schalk et al. (2010), HRM practices influence the way in which people of different ages behave in organizations.

Regarding, “What happens in the organization where I work”, “Performance Evaluation” (3.61) is the dimension that the respondents are most aware of. The reason why this is one of the HRM practices workers most identify may be related to the fact that the organizations have specific assessment tools, a defined period of time to carry out the assessment and also because the result of this evaluation frequently has consequences for workers. The dimension “Job Security” shows the lowest average score (2.66). Our results indicated that instead of “Job Security”, as identified in the literature, employees now placed greater emphasis on “Training”, “Rewards, Recognition and Participation”. This result may be a consequence of the high national rate of unemployment, as well as the recent changes to work contracts. On the other hand, “Job Security” is the dimension that shows the most consensus among the respondents (lower standard deviation), while “Training” is the one that registers more heterogeneous responses (higher standard deviation).

Regarding “To what extent it is important to me”, the dimensions “Training”, “Rewards, Recognition and Participation” and “Performance Evaluation” are the most valued by respondents. Concerning “Training”, it seems that workers of all ages have the perception that it is crucial for organizations to offer training opportunities throughout their active working life, as well as to ensure that all workers have career opportunities, regardless of their age. Additionally, Armstrong-Stassen (2008) states that recognition and respect are the HRM practices that older workers most value and the ones to which they attach most importance. In the same sense, McEloy and Blahna (2001) report that the lack of recognition of workers’ skills, and the feeling that they are not respected by the management, are two of the main reasons why older workers leave the organization. These results demonstrate the importance of implementing and promoting practices associated with the recognition of workers, particularly in order to retain them in organizations.

Curiously the dimension of “Flexible Work Practices” is the one that registers the lowest average score. Flexible working practices are associated with greater job satisfaction, lower stress levels, improved productivity, better work-life balance, as well as fewer working hours lost through delays, and lower levels of absenteeism (Sparks, Faragher, & Cooper, 2001). The fact that respondents do not value flexible working practices, despite the enumerated advantages, may be explained by the fact that only a few organizations offer this type of opportunity and many workers are still unaware of its advantages. The dimension, “Job Design” is the one that gathers most consensus among the respondents (lower standard deviation), while “Job Security” is the one that registers more heterogeneous responses (higher standard deviation).

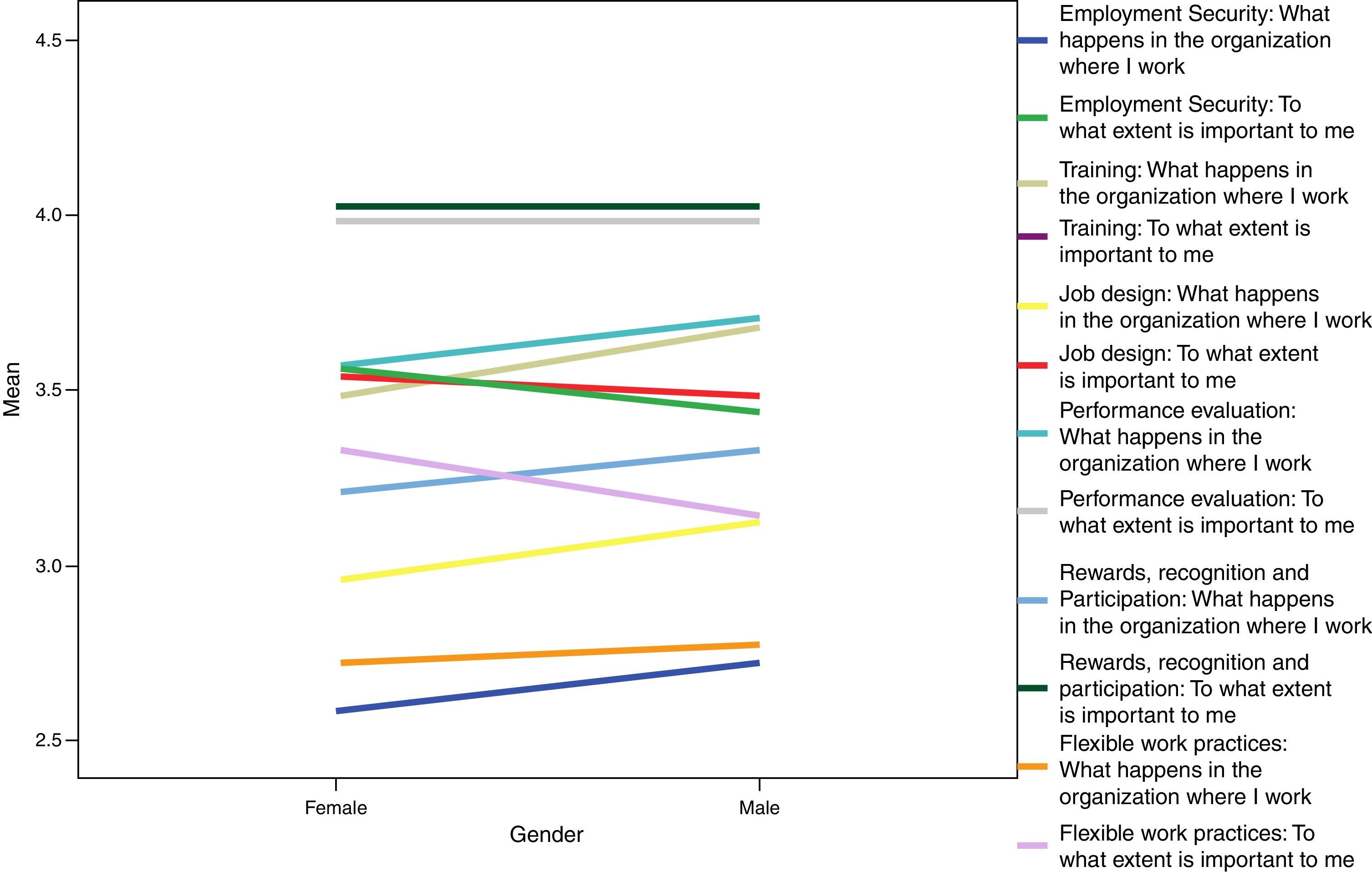

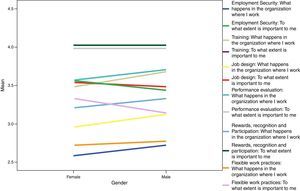

Differences in the scores obtained, in the various dimensions and based on the socio-demographic characteristics considered relevant for the analysis, were then investigated. Statistically significant differences in scores by gender (Fig. 1) were found for the dimensions of “Job Security”: What happens in the organization where I work (p=0.044), and “Job Design”: What happens in the organization where I work (p=0.029) and “Flexible Work Practices”, as well as to what extent it is important to me (p=0.012). Women tend to have lower scores in the first two dimensions and higher in the last. The development of Portuguese society continues to demonstrate changes that should be considered globally as largely positive for the situation of women. One example is the increased participation of women in an active life and moving to a model of more continuous activity, with fewer interruptions for family reasons. This may be due to public policies that have had a direct impact on increasing female employment, such as fixing the minimum wage, unemployment benefits, maternity leave and family care. However, there is still a paradox in Portuguese society, i.e., despite the feminization of education and the job market, women continue to be segregated and discriminated against. Therefore, it appears that the assimilative capacity of these transformations in the Portuguese economy remains limited (Ferreira, 1999). Apart from the fact that women's work is undervalued, it is also known that this is one of the groups with the highest employment instability (Rebelo, 2002). Also, women's role of family caregiver overlaps the need for security and it is mainly women who benefit from new job setups that allow them to balance work and family, and in that sense “Flexible Working Practices” are indicated as a way that contributes to such harmonization (Pinto, 2003).

Findings suggest that both sexes attach the same importance to the practice of “Rewards, Recognition and Participation” and “Performance Evaluation”, as we can see in Fig. 1.

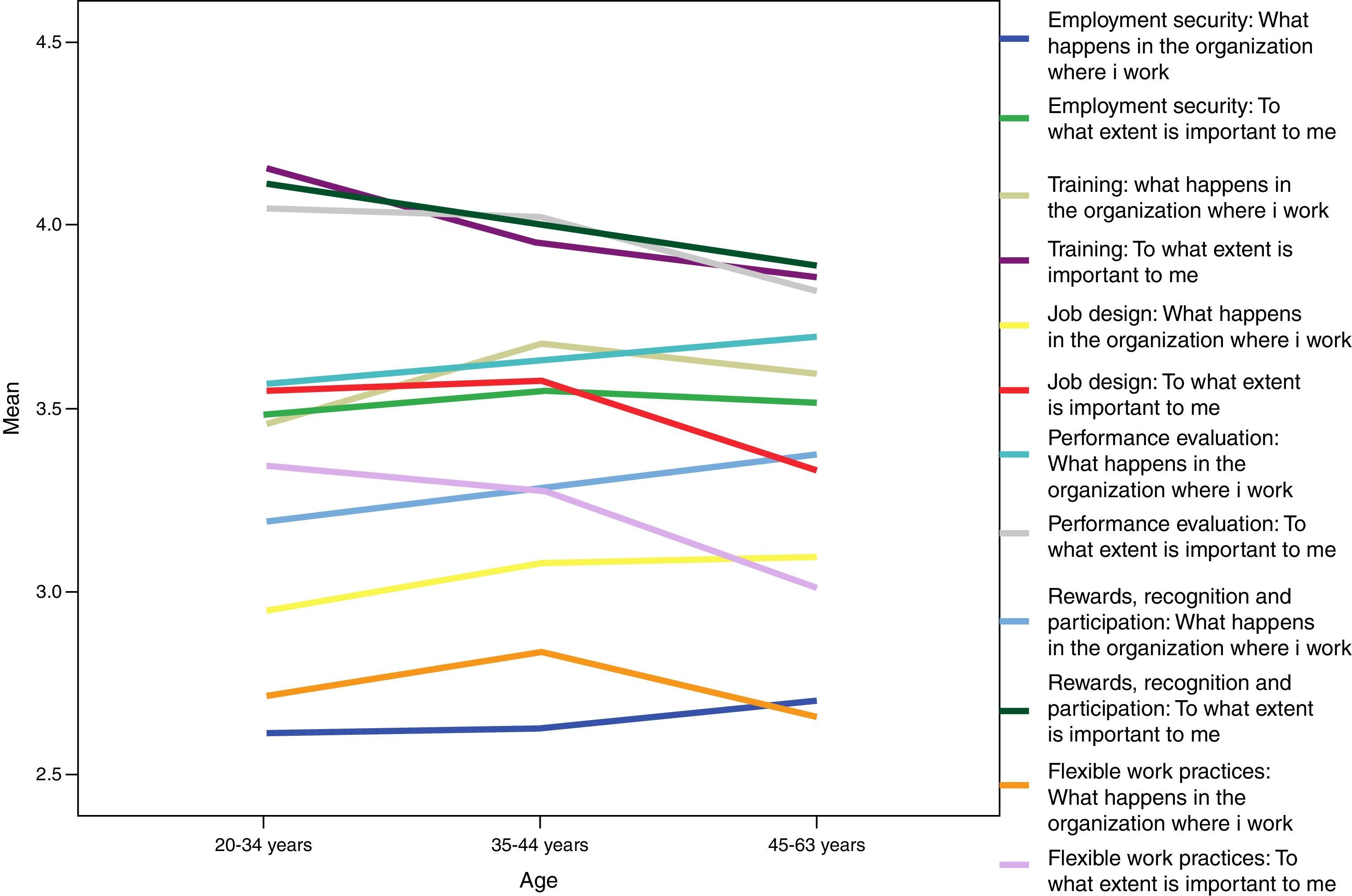

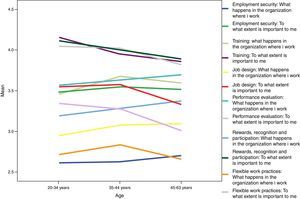

- (1)

The lines “Rewards, Recognition and Participation” and “Training” overlap, making the latter invisible.

Statistically significant differences were found in the scores based on the age of the respondents (Fig. 2) for the dimensions “Training”: What happens in the organization where I work (p=0.026), “Training”: To what extent it is important to me (p=0.001). The employees in the intermediate group, aged between 35 and 44, are the ones that are more aware of the existence of training in the organization. However, younger workers (20–34) are those who attribute the greatest importance to this practice, which means that training is the practice that has most impact on the intention of the workers to remain in the organization (Bowen & Ostroff, 2004). There are also statistically significant differences in the scores based on the age of the respondents for the dimensions: “Job Design”: To what extent it is important to me (p=0.005), “Rewards, Recognition and Participation”: To what extent it is important to me (p=0.046) and “Flexible Work Practices”: To what extent it is important to me (p=0.007). These three dimensions obtained lower scores from the respondents with higher ages (43–63), findings which suggest that, as workers get older, they recalibrate their scale of values and attach less importance to HRM practices.

The emphasis on “Training”, “Rewards, Recognition and Participation” and “Performance Evaluation” is consistent in the three age groups, and it was found that regardless of age, all workers consider these practices as very important. These results corroborate previous studies, since both younger and older workers consider that the development of human resources means new learning (Tamminen & Moilanen, 2004). Stork (2008) also stresses the importance of accessing new learning, such as taking pride in your performance and feeling respected by the supervisor. In fact, employees relate recognition of a good performance with expecting something in return for their work (Babcock, 2005).

In short, and as Kinnie et al. (2005) state, each individual experiences HRM practices differently and different groups of workers do not respond in the same way to these practices.

7ConclusionEmployers in an aging society will inevitably be confronted with the economic challenges tied to an aging workforce. The design of HRM practices to increase the employability and the intention of employees to continue working two of the important challenges that human resource managers face in the future. As older workers become a significantly larger portion of the workforce, organizations must retain the special talents, extensive knowledge, and relevant experience of older workers in order to stay competitive.

Regarding the findings of this study, it can be concluded that “Training” and “Rewards, Recognition and Participation” are the HRM practices most valued by workers of all ages, while our participants perceived the “Performance Evaluation” as the most effective HRM practice.

As regards training and in agreement with the claim defended in the lifespan theory (Baltes, Staudinger, & Lindenberger, 1999), although the need to progress seems to decrease with age, the effect of training and development practices do not decline with age. In the opinion of Kooij et al. (2010), although older workers do not necessarily want to progress in their work anymore, they still want to invest in training and development activities to prevent obsolescence and constriction. According to Huselid (1995), providing formal and informal training experiences, such as basic skills training, on the-job experience, coaching, mentoring can further influence employees’ development. Our results show that the human resource training and development practices are just as important for older workers as for the younger ones. Some authors have even argued that human resource training and development practices are particularly important for older workers (Armstrong-Stassen & Ursel, 2009). Further, workers of all ages attach great importance to performance evaluation because it is through this that performance is recognized and rewarded. It is recommended that this practice could be taken into consideration during the strategic planning of the workforce in an “age conscious” organization. Considering the tight link between performance evaluation and incentive compensation systems, the use of internal promotion systems that focus on employee merit and other forms of incentives to align the interests of the employees with those of the shareholders is crucial. Furthermore “HRM practices can affect employee motivation by encouraging them to work harder and smarter” (Huselid, 1995:637).

Different studies about HRM practices, namely training, compensation and rewards, have revealed that these can lead to: reducing turnover and absenteeism, increasing productivity, a better quality work, and better financial performance (Arthur, 1994; Huselid, 1995; Meyer & Allen, 1991). Another important contribution of this study was to realize that there is a dissonance between the HRM practices that employees most valued and those they perceive as existing in their organization. According to Schalk (2007), it is central to understand how the motivations, personal preferences and attitudes change and develop over time and know what impact these changes have on the job. This requires listening to, and promoting the participation of, workers in the design and implementation of these HRM practices, because only in this way will it be possible to attract and retain workers in organizations.

The commitment of employees to an organization is an outcome of the support perceived from the organization (Eisenberger, Huntington, Hutchinson, & Sowa, 1986; Stettoon, Bennett, & Liden, 1996). According to Kooij et al. (2010), workers see the HRM practices as an investment in them and as a recognition of their contributions to the organization, so employees feel they should give something back to the organization through positive attitudes. Although most current organizations opt for policy formulation strategies that reflect their own cultures and priorities, the critical issue is whether the employees have been consulted, and whether the resultant policy reflects a compromise between management and employee interests. The non-alignment between the organization's effective practices and the practices workers deem important, seems to make evident that there is still much work to be done in this area, emphasizing the importance of developing practices tailored to the workers’ needs and desires. Like Armstrong-Stassen (2008), we believe that considering the needs of older workers will encourage the most engaged employees to stay, which may have positive consequences in responding to the scarcity of the workforce and talent, as well as to the loss of skills and institutional memory in the near future.

In this sense, we consider that our study may be a starting point for further research on the possible support factors involved in the age issue, since there is a relationship between the perception of HRM practices, employability and the intention to remain active.