Performance Management brought new dimensions of public management (thinking in terms of output and outcome, accrual accounting). However, the complex dimensions of politics asked for more complex management systems allowing a better consideration of non-economic dimensions of politics. Multidimensional strategic planning has been developed. Furthermore, internal administration and external (and parliamentarian) communication have different information needs. Information must be tailored to the context and levels of public authorities.

It is now 10 years ago since the fourth biennial Conference of CIGAR in St. Gallen on Performance Management and Public Accounting. Since the early evolution of the “bureaucratic revolution” in New Zealand it was clear that performance specification and accrual accounting are the two sides of the same coin (Pallot, 1994: 219). After Hood's contribution (Hood, 1991) the term “New Public Management” or “NPM” was more and more used as well by intergovernmental organisations like OECD or the World Bank. NPM has never been a homogeneous theory, rather different nations developed similar approaches, often in cooperation with consultants. The one common ground of all approaches was to overcome the shortcomings of classical budgeting (Buschor, 1994: vi):

- •

input oriented pattern;

- •

lack of strategic priorities;

- •

strong centralisation;

- •

pronounced thinking in terms of year;

- •

lack of alternatives;

- •

insufficient budget flexibility and

- •

cash based (not accrual based) accounting.

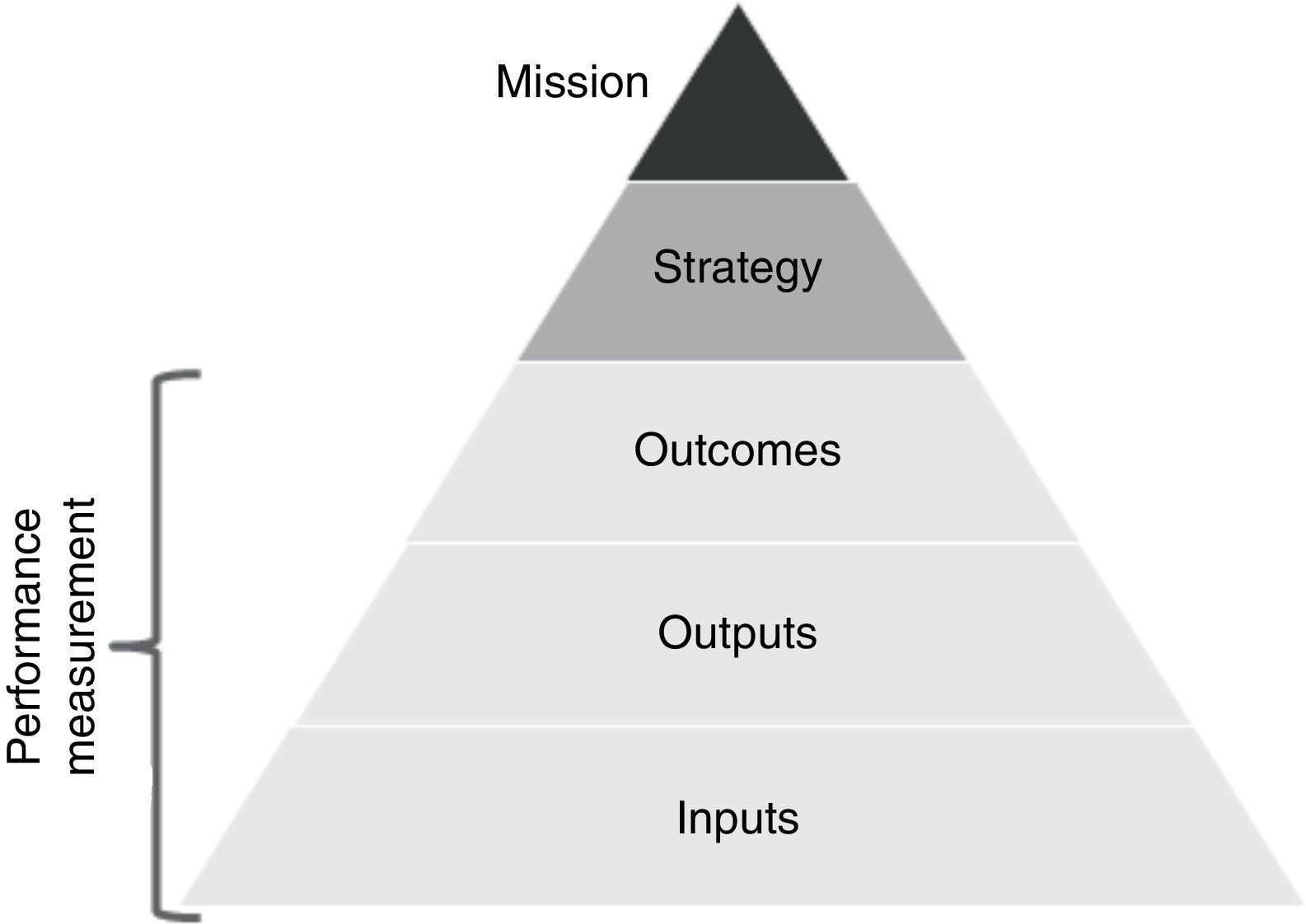

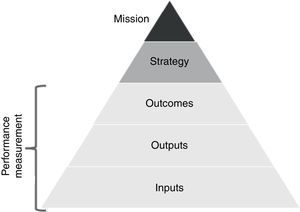

In summary, Performance Management is a central tool for a management style that takes decisions not primarily based on (financial) input, but focuses on outcome and output. Performance Management needs to be based on a strategy and – in most countries – on a legal mission (Fig. 1).

Combining the five above mentioned elements allows as a consequence the delegation of operative management to the administration/bureaucracy; or in other words to the devolution (enabling state model). Given the variety of local and democratic regimes and traditions (federalistic, centralistic), NPM has lead to a wide range of models of delegation, devolution and privatisation.

Overall, OECD noticed that performance budgeting is “widespread across countries” and has the following advantages (OECD, 2007: 11):

- •

sharper focus on results;

- •

better information on government goals and priorities;

- •

provides key actors with details on what is working and what not;

- •

improves transparency;

- •

has the potential to improve programmes and efficiency.

It is generally recognised that Performance Management “mediates the effect of innovation on performance and have a positive influence of its own” (Walker et al., 2011: 381).

2Limited measurability of outcomesHowever, there have been critical voices since the early phase of Performance Measurement, namely regarding measurability of qualitative effects and the high cost of Performance Measurement. The criticisms of Rowan Jones is representative for this discussion (Jones, 1994: 56): “Since we know that the numbers resulting from this performance measurement cannot reflect the underlying ‘production technologies’, using the numbers to manage, without an equal weighting being given to the unmeasurable will not necessarily mean better performance. Intuitively, accountants know that ‘quantified goals drive out unquantified ones’: the recent imperative for ‘quality insurance’ emerged that this provides is that relates to the numbers that are the cause of the problem not to the quality, which is not. The costs of performance measurement could be very high indeed and the improved accountability and management of public services will have to be commensurately higher to justify the change, particularly in a cash-limited zero-sum game. The basic theses of this paper can also be used to suggest that we will never be able to evaluate this.”

In a similar form OECD mentions as well as a criticism on superfluous data production (OECD, 2003: 3) “The growing popularity of performance measurement around the budget and reporting process … often creates flows of superfluous information that nobody.”

A further criticism is the limited measurability of indicators, especially of outcome indicators, which was a key reason to further develop the internationally well known New Zealand Model. As Pallot points out (Pallot, 1998: 14) “Inevitably, there are some tensions between the outputs-outcomes accountability framework and the framework for strategic management. The former relies on tight specification of “contracts” and measurability. It is less detailed but comprehensive in the sense of covering all activities of government. By contrast, the strategic management framework is more “holistic”, it is oriented to the medium to longer term rather than the current period, makes more extensive use of “soft” information and is oriented towards processes (within a vision that generates commitment) rather than contracts, documents and plans as such. Rather than covering all departmental activities, it aims to focus on a few genuine strategic objectives. … In sum, the shift has been from management in the public sector to management of the public sector; that is from defining management in terms of where it takes place to define it in terms of the nature of the task.”

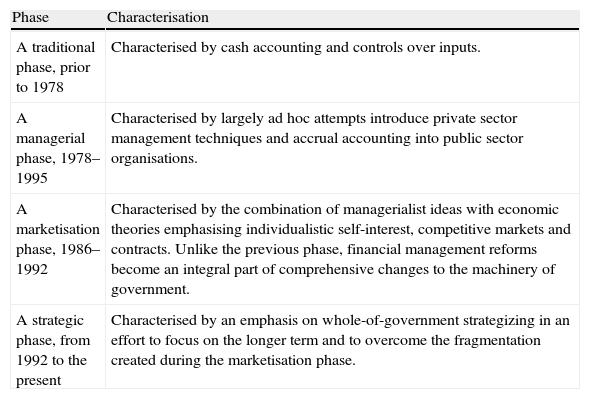

The above mentioned weaknesses lead in New Zealand to an evolution of the Performance Measurement concept, combining Performance Management with strategic. As was referred by Pallot (1998: 14), locking back over the last twenty years it is possible to identify four phases of public management in New Zealand (Table 1).

The evolution of Performance Management in four phases.

| Phase | Characterisation |

| A traditional phase, prior to 1978 | Characterised by cash accounting and controls over inputs. |

| A managerial phase, 1978–1995 | Characterised by largely ad hoc attempts introduce private sector management techniques and accrual accounting into public sector organisations. |

| A marketisation phase, 1986–1992 | Characterised by the combination of managerialist ideas with economic theories emphasising individualistic self-interest, competitive markets and contracts. Unlike the previous phase, financial management reforms become an integral part of comprehensive changes to the machinery of government. |

| A strategic phase, from 1992 to the present | Characterised by an emphasis on whole-of-government strategizing in an effort to focus on the longer term and to overcome the fragmentation created during the marketisation phase. |

Similar developments took place in the United States In 1993, the federal government introduced the Government Performance and Result Act mainly based on Performance Management. In 1997 this act was substantially revised with a combination of Performance Management and five-year strategic planning. Radin commented these changes as follows (Radin, 1998):

- •

improve confidence of people in government;

- •

stimulate reforms;

- •

focus on results, service quality and public satisfaction;

- •

improve service delivery;

- •

improve congressional decision making.

Some agencies within federal establishments may be using the requirement to achieve internal management agendas, but the complexity of the institutions of American Governance works against the accomplishment of the rational goals of the legislation. Schick resumes this dilemma as following (Schick, 2007: 137) “Neither performance budgeting nor accrual budgeting is ready for widespread application as a decision rule. Both have unresolved issues and are costly to implement. In performance budgeting, the key issue is the extent to which resources should be linked to results; in accrual budgeting, the issues are much more complex and involve the valuation of assets, recognition of revenues, treatment of depreciation and capital charges, and other unresolved questions. The four countries that have adopted accrual budgeting have taken different approaches, their experiences should provide a former basis for assessing accruals in the future”.

Although they are distinct accounting and management innovations, Schick (2007) highlights performance budgeting and accrual budgeting because they share a dependence on robust, result-oriented management and full cost attribution. In fact, these qualities are absent in most countries and in consequence the suitability of performance and accrual systems is limited. So, it is not surprising therefore, that countries which have adopted Performance Management also used features of accrual budgeting.

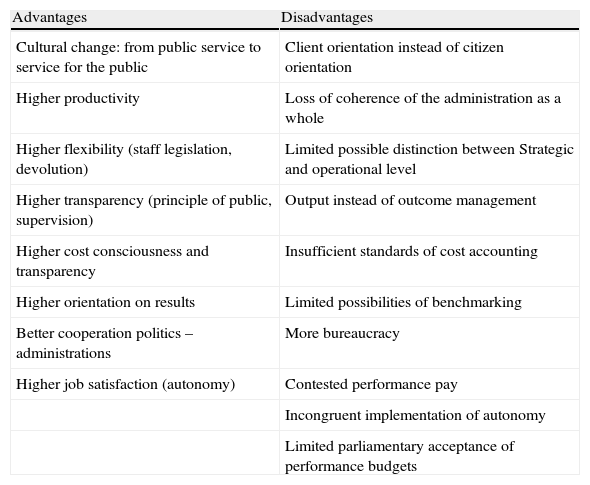

In Switzerland, new models of NPM also display a combination of strategic planning and Performance Management based on accrual accounting. Comprehensive evaluations of Swiss NPM models evidence the following portfolio advantages and disadvantages presented in Table 2.

Advantages and disadvantages of NPM models.

| Advantages | Disadvantages |

| Cultural change: from public service to service for the public | Client orientation instead of citizen orientation |

| Higher productivity | Loss of coherence of the administration as a whole |

| Higher flexibility (staff legislation, devolution) | Limited possible distinction between Strategic and operational level |

| Higher transparency (principle of public, supervision) | Output instead of outcome management |

| Higher cost consciousness and transparency | Insufficient standards of cost accounting |

| Higher orientation on results | Limited possibilities of benchmarking |

| Better cooperation politics – administrations | More bureaucracy |

| Higher job satisfaction (autonomy) | Contested performance pay |

| Incongruent implementation of autonomy | |

| Limited parliamentary acceptance of performance budgets |

Current efforts intend to resolve or reduce problems and to promote advantages. The Swiss Performance Measurement is therefore in an evolutionary phase, similar to what we can observe in other countries. Therefore, NPM has to be understood rather as a movement and less as a coherent or stable model.

NPM stays still in an evolution process. Robert and Francois considered GPRA in its new form as “laudable effort”. “If people are more sensitive to losses than to gains, than loosers will invest more blocking (or undermining) than winners do achieve gains” (Robert & Francois, 2003: 93). However, in the reality much more investments in accounting, information systems and human resources are needed to achieve these improvements (Robert & Francois, 2003).

Recent empirical analyses criticise the enormous amounts of data necessary, often exceeding parliamentarian analytical capacities. Robinson concludes for the Netherlands (Robinson, 2009: 125) that “The attention of members of parliament for the annual report remains rather low. Interest tends to be confined to the parliamentary finance commission.” Bogumil, Ebinger, and Holtcamp (2011) go for the German context much further, concluding the following “Deficits of transparency and possibilities of manipulations of administrations … high transaction cost of accrual accounting … increasing uncovered balance sheets without consequences … controllers without impact reduce the usefulness of the approach so far, that in the heart communes practice muddling through and incremental approaches. … The reduction to input-oriented amounts is a rationale method of complexity reduction” (Bogumil et al., 2011:175).1 A way back to muddling through is a risk, though this is not an effective solution, as Robinson and Brumby (2005) pointed out in a comprehensive literature analysis “Taken as a whole, literature does not provide the grounds to the believe in strong form of budgetary incrementalism. … Effective performance budgeting is not incompatible with some degree of incrementalism in budgeting (Robinson & Brumby, 2005: 25).” On the other hand, Schädler and Proeller (2005) underline the fact that different rationales and patterns dominate political decisions. “Politics and management constitute two worlds with different thought patterns, conceptualisations and sanctioning and rewarding mechanisms (Schädler & Proeller, 2010). This results in rationalities of thought and action which differ from politics and management. What is political rational may strike management as irrational. Whereas management makes decisions based on facts, politics depends on majorities, which, in turn, tend to be the result of complex negotiation processes, where consent and rejection are bartered for things that are often only loosely connected. Politics and management are frequently equally objective-oriented; however, the way towards achieving goals can differ fundamentally. The art of leadership in the politico-administrative system consists of drawing the best out of both worlds by means of skilful combination. Newer concepts of Performance Measurement consider different “rationalities” of performance like this has been still done in earlier phase of evolution theory.

As outlined above, Performance Measurement allows only a limited transparency on (often diffuse) “rationalities”. One way to circumvent this, would be to increase complexity of Performance Measurement, allowing more differentiated analyses. The drawback of more complexity is that especially users outside administrations cannot (or are not willing to learn) to interpret multi-dimensional charts that are conceived as more informative balanced scorecards by experts.

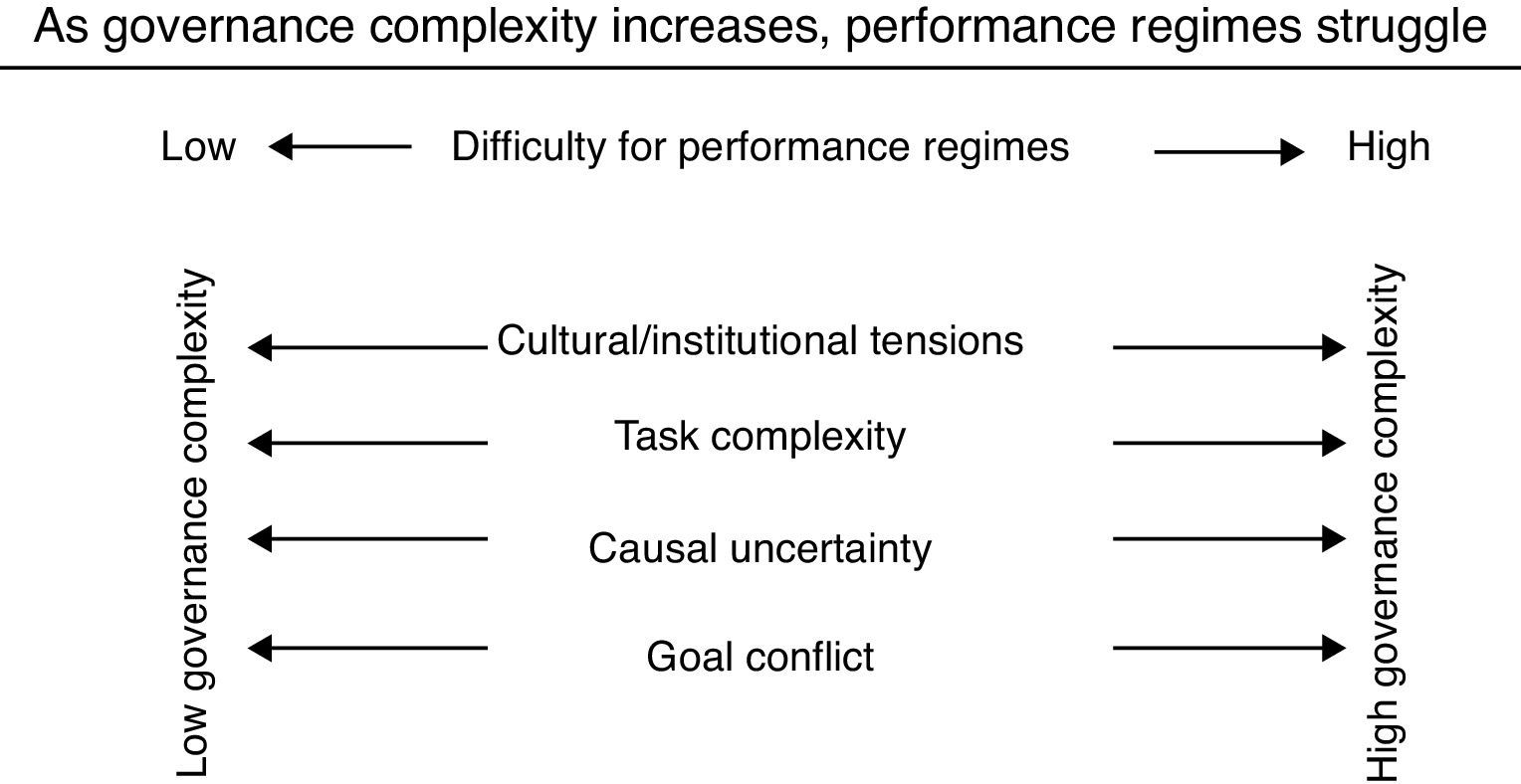

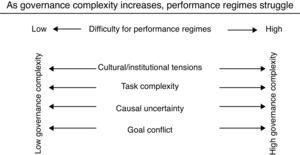

Experience of direct democracy in Switzerland shows that political discussions tend to concentrate on a very few or even one a main argument. Public discussions should therefore be based on few arguments or indicators, even if such simplistic decision making can be problematic. The recent Swiss popular vote of June 2012 on the introduction of a “gatekeeper model” in health illustrates this problem. Initially, the main reasons to support the vote were cost savings in the health care sector. However, a few weeks prior to the vote, the debate turned almost exclusively to the fact the proposal restricted the free choice of doctors. The advantage of lower cost was blended out almost entirely and the law proposal has been rejected by a large majority of voters. The following model of Moynihan and Fernandes shows the complexity of performance presentation (Fig. 2).

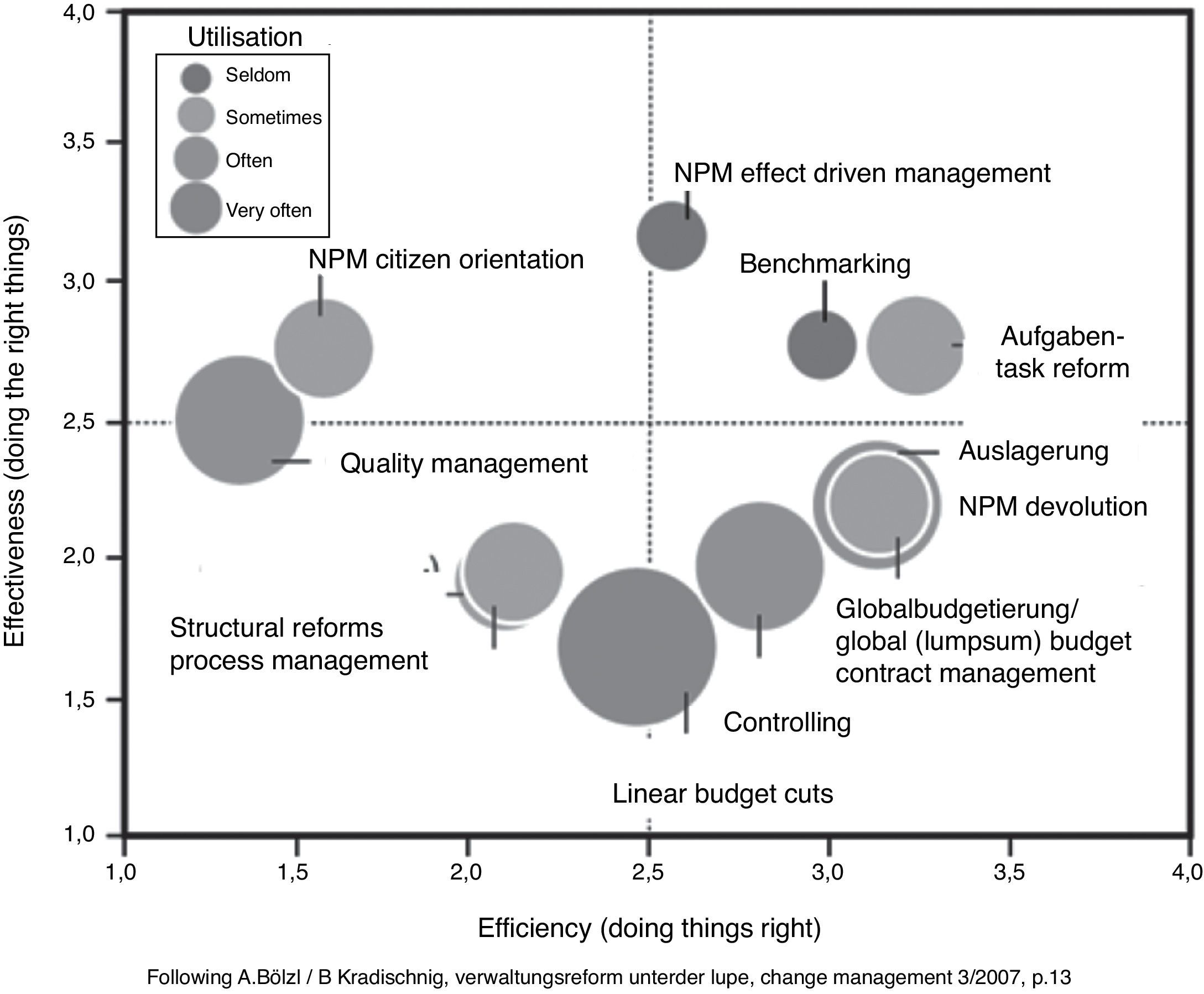

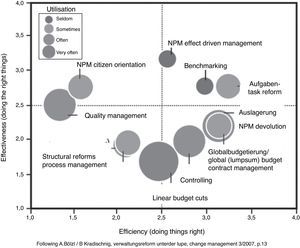

Theory and practice in the German speaking countries underline the use as well as the necessity for a multi-instrumental approach. The following chart provides an overview of major management instruments, including schematic efficiency and effectiveness of some instruments as well as their utilisation. Linear budget cuts are still mostly used. However, the scale of instruments is broad. These multiple approaches are presented by Pölzl and Kradischnig (2007) (Fig. 3).

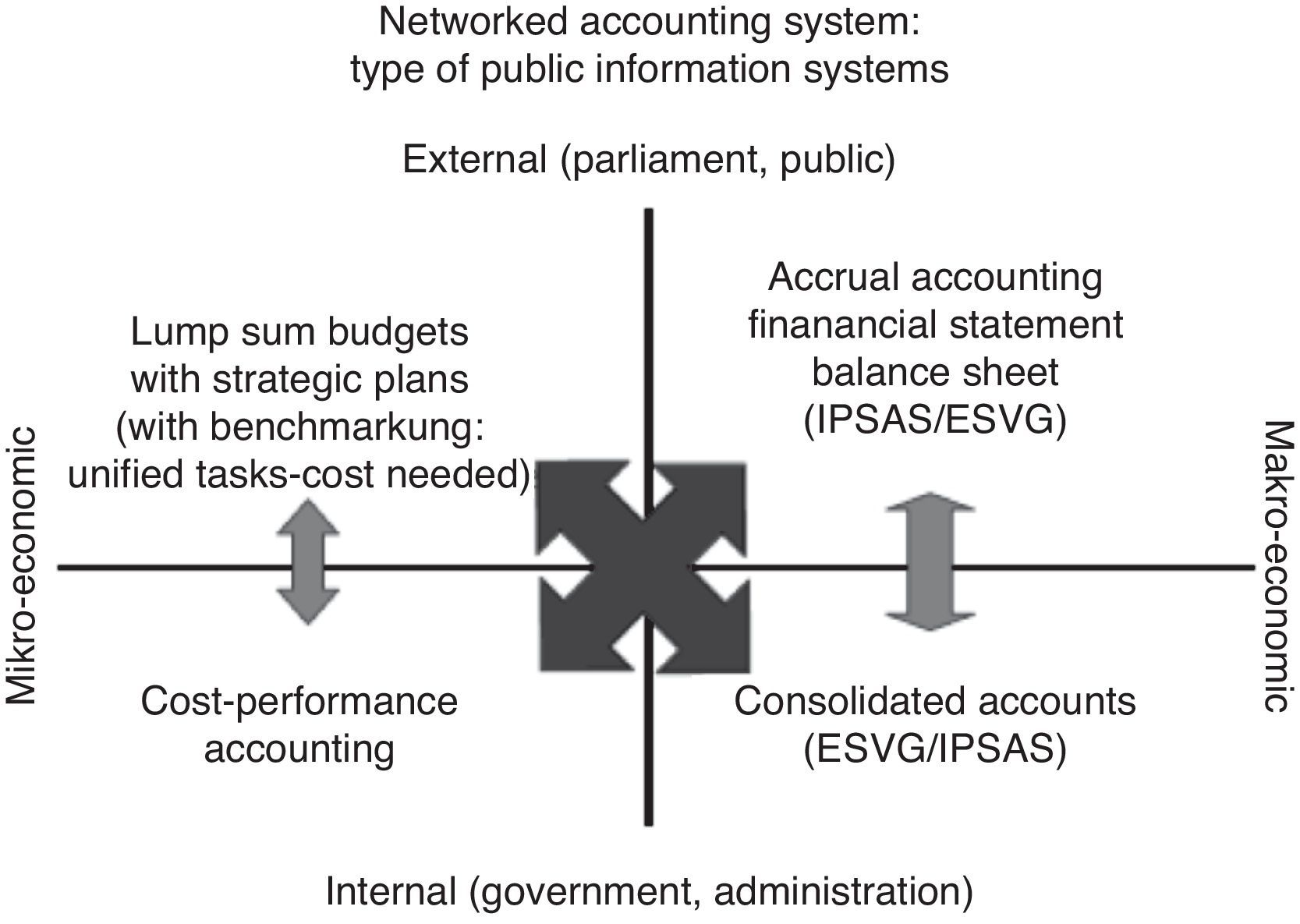

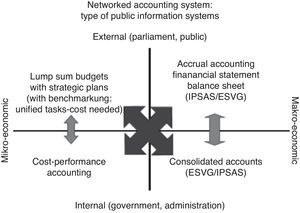

The variety of approaches raises the question of who uses what instrument and which information is distributed to whom (acting bodies within and outside of administration). Internally, the full range of instruments should be available for internal management only. Regarding information distribution: external information must be concentrated and limited, but internal information should be available for relevant parliamentarian commissions as well as the public (internet). At least the following four instruments should be used.

- -

strategic planning with coordinated lump sum budgets should be the main base for parliamentarian mean allocation;

- -

detailed operational performance data should serve to run devoluted administrations in combination with incentives for service units and staff;

- -

accrual accounting should ensure that each generation covers its consumption;

- -

consolidated accounts give an overview of externalised units and prove total cost (generation) coverage.

Switzerland was an innovator of introducing financial performance indicators. They have ensured, especially if combined with institutional “debt brakes” (i.e. in the Canton of St. Gallen since 1927) an actual excellent performance of all government levels in Switzerland.

3ConclusionsIn sum, this paper reflects on some perspectives on performance measurement eighteen years after his co-edited book, addressing a multidimensional perspective. While acknowledging that Performance Management brought new dimensions to public management (output and outcome orientation, accrual accounting, etc.), the author underlines that the complex dimensions of politics ask for more complex management systems allowing a better consideration of non-economic dimensions of politics.

The paper calls attention for Performance Management limits, particularly discussing those relating to the limited measurability of outcomes as well as to the low interest of parliamentarians in complex issues and different thought patterns between politics and management.

It is highlighted that performance information (including programme budgeting) must be tailored to the context and levels of public authorities, considering that internal administration and external (and parliamentarian) communication have different information needs. Complexities inherent to Performance Management implementation must also be taken into account.