Herpes zoster (HZ) is a relatively common disease whose incidence increases with age and in immunocompromised situations. Mortality caused by HZ is low, but its complications impact on physical, psychological, functional, and social aspects of patients, significantly reducing health-related quality of life. Post-herpetic neuralgia is the most common complication, and is characterised by symptoms of neuropathic pain including allodynia and hyperalgesia with electrical, burning, and/or stabbing sensations that persist more than 90 days. Its management is complex and has limitations, which increases the demand for health resources and also increases direct and indirect costs. This article reviews the epidemiological and clinical features of HZ, the available treatments and vaccines against HZ, as well as national and international vaccination recommendations. In addition, the role of primary care is emphasised as a catalyst for the implementation of adult vaccination.

El herpes zóster (HZ) es una enfermedad relativamente común cuya incidencia aumenta con la edad y en situaciones de inmunocompromiso. El HZ presenta una baja mortalidad, pero sus complicaciones tienen un gran impacto en aspectos físicos, psicológicos, funcionales y sociales de los pacientes, reduciendo significativamente la calidad de vida relacionada con la salud. La neuralgia posherpética es la complicación más frecuente y se caracteriza por síntomas de dolor neuropático que incluyen alodinia e hiperalgesia con sensaciones eléctricas, urentes y/o punzantes que persisten más de 90 días. Su tratamiento es complejo y tiene limitaciones, lo que aumenta la demanda de recursos sanitarios y de gastos directos e indirectos. Este artículo revisa las características epidemiológicas y clínicas del HZ, los tratamientos y vacunas disponibles, así como las recomendaciones nacionales e internacionales de vacunación. Además, se enfatiza el papel de la Atención Primaria como catalizador para la implementación de la vacunación de adultos.

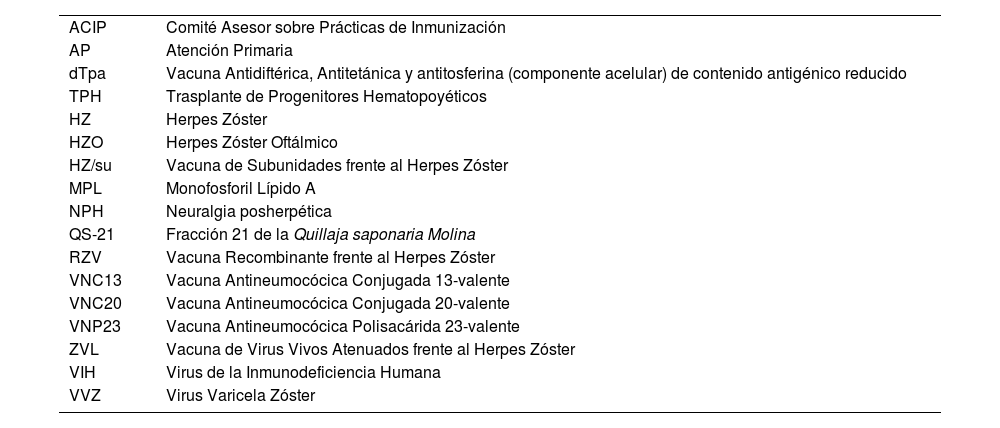

| ACIP | Comité Asesor sobre Prácticas de Inmunización |

| AP | Atención Primaria |

| dTpa | Vacuna Antidiftérica, Antitetánica y antitosferina (componente acelular) de contenido antigénico reducido |

| TPH | Trasplante de Progenitores Hematopoyéticos |

| HZ | Herpes Zóster |

| HZO | Herpes Zóster Oftálmico |

| HZ/su | Vacuna de Subunidades frente al Herpes Zóster |

| MPL | Monofosforil Lípido A |

| NPH | Neuralgia posherpética |

| QS-21 | Fracción 21 de la Quillaja saponaria Molina |

| RZV | Vacuna Recombinante frente al Herpes Zóster |

| VNC13 | Vacuna Antineumocócica Conjugada 13-valente |

| VNC20 | Vacuna Antineumocócica Conjugada 20-valente |

| VNP23 | Vacuna Antineumocócica Polisacárida 23-valente |

| ZVL | Vacuna de Virus Vivos Atenuados frente al Herpes Zóster |

| VIH | Virus de la Inmunodeficiencia Humana |

| VVZ | Virus Varicela Zóster |

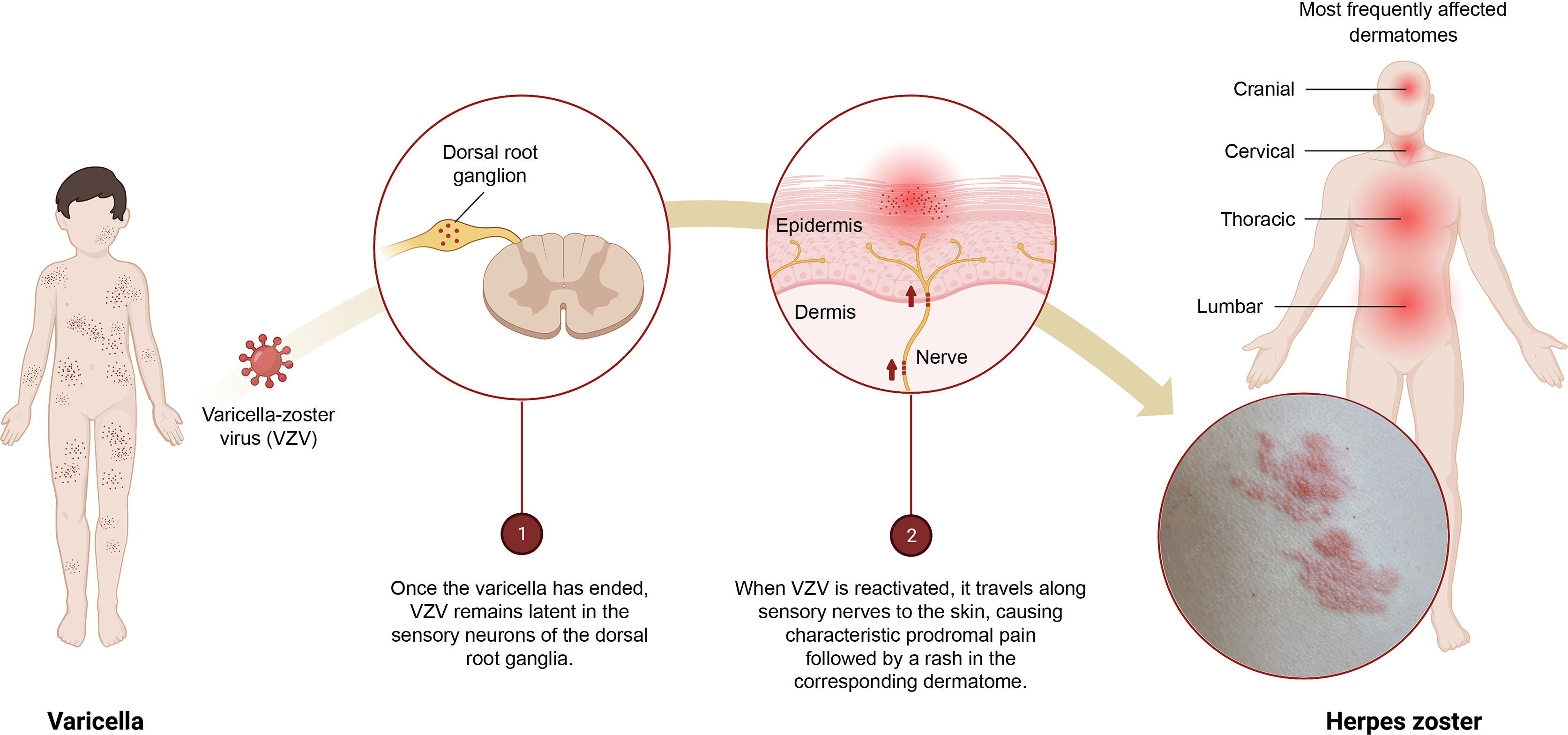

Herpes zoster (HZ) is a common disease (up to 1 in 3 people may experience it during their lifetime) that can significantly affect patients' quality of life.1 It is the neurocutaneous manifestation of an opportunistic reactivation of the varicella-zoster virus (VZV) (Fig. 1). In most countries, including Spain, more than 90% of adults have been infected with VZV and could therefore develop HZ.2

Infographic on the primary infection–latency–reactivation of the varicella-zoster virus (VZV).

1) Once the varicella episode has ended, VZV remains latent in the sensory neurons of the dorsal root ganglia.

2) When VZV is reactivated, it travels along the sensory nerves to the skin causing characteristic prodromal pain followed by a rash in the corresponding dermatome.

The main symptom of HZ is intense pain, which accompanies a pathognomonic dermatomic vesiculobullous erythema that generally resolves within a month after the appearance of the lesions. There are atypical presentations, such as unilateral pain without skin lesions (herpes zoster sine herpete) or bilateral involvement. Recurrences and disseminated disease are more common in immunocompromised people.

Other complications that may appear are: (1) post-herpetic neuralgia (PHN), the most frequent complication (affects 5%–30% of patients), which is defined by the persistence of pain in the affected areas beyond 3 months from the appearance of skin lesions or acute infection; (2) trigeminal involvement that triggers ocular (herpes zoster ophthalmicus [HZO]) or ear (Ramsay-Hunt syndrome) involvement; (3) bacterial superinfection; and (4) neurological involvement, among others.3–5

The development of safe and effective vaccines to prevent HZ also addresses the prevention of its complications, an improvement in patients' quality of life and the efficient use of health resources. Health personnel, especially primary care (PC) professionals, play an important role as they inform patients and promote preventive interventions, such as vaccination, achieving a model of social sustainability based on healthy ageing.

Herpes zoster as a public health problemAlthough HZ-related mortality is low, pain and its associated complications constitute a major public health problem in Spain. The incidence of HZ and PHN increases after the age of 50, with age being the main risk factor. Immunosuppression, as a result of diseases (autoimmune, neoplasia, human immunodeficiency virus [HIV] infection) or certain treatments, also considerably increases the risk of experiencing HZ, together with some infections that affect cellular immunity, such as COVID-19 or highly common chronic diseases, such as diabetes mellitus, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, or asthma.2,6

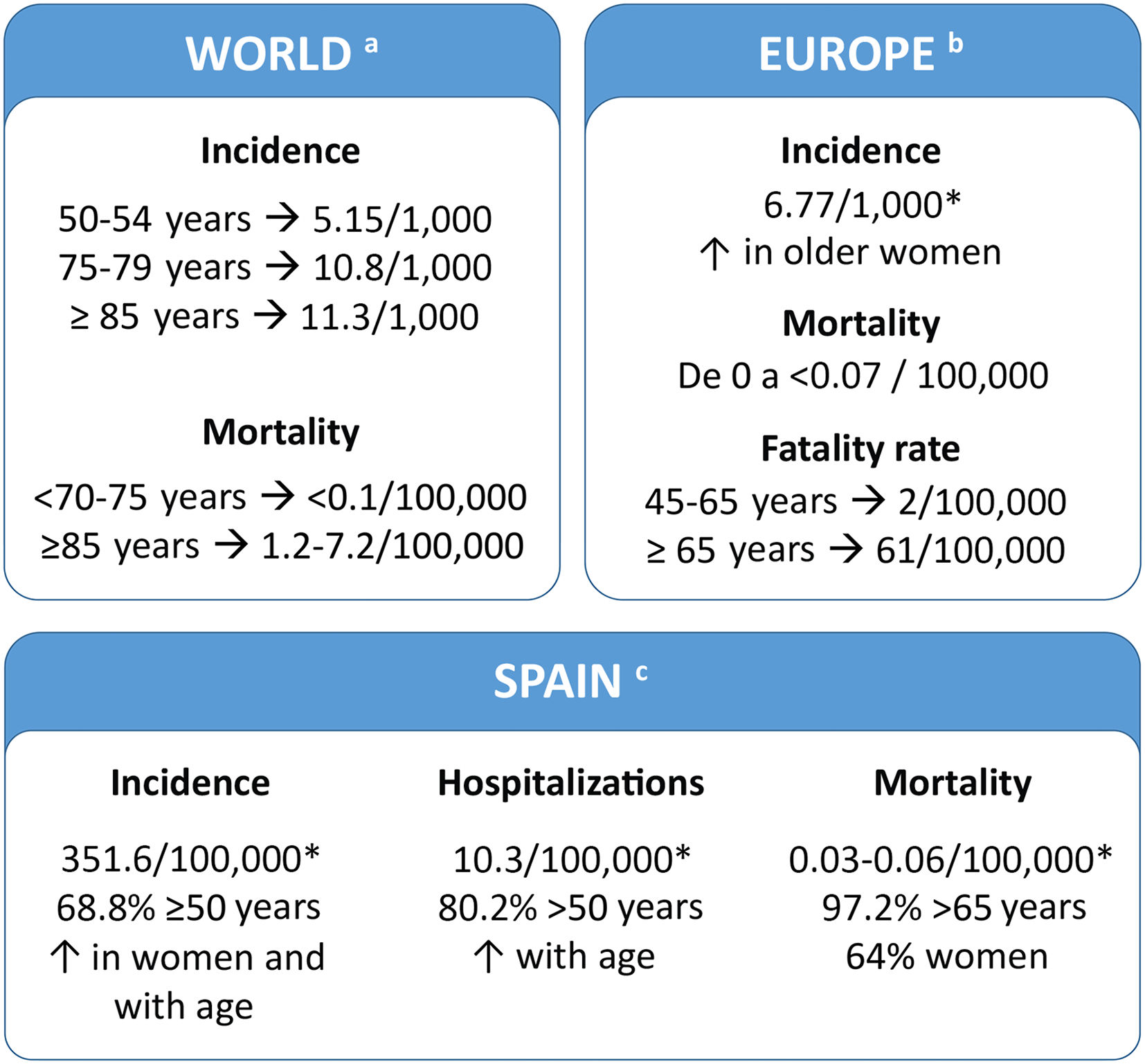

Disease burdenThe HZ burden is similar in all developed countries. In Spain, 68.8% of patients are ≥50 years old (Fig. 2). Several studies have evaluated the use of healthcare resources and the economic burden of HZ in Spain and these studies indicate that they increased in older people. (Supplementary table 1).7–11 A recent study showed that the cost of treating HZ and PHN per patient was €240 and €571, respectively (National Health System perspective). If non-health costs are added (social perspective), the cost increases to €296 and €712, respectively.7

Patients' quality of lifeAlthough the acute phase of HZ is self-limiting, acute pain and HZ-related complications particularly PHN, greatly impact patients' health-related quality of life.4 The pain may be constant or intermittent and unbearable and presents with hyperalgesia and/or allodynia. It is described as electric, burning, stabbing, lacerating, or shooting and its duration is indeterminate. It can disappear in months or years, or remain forever.17,18

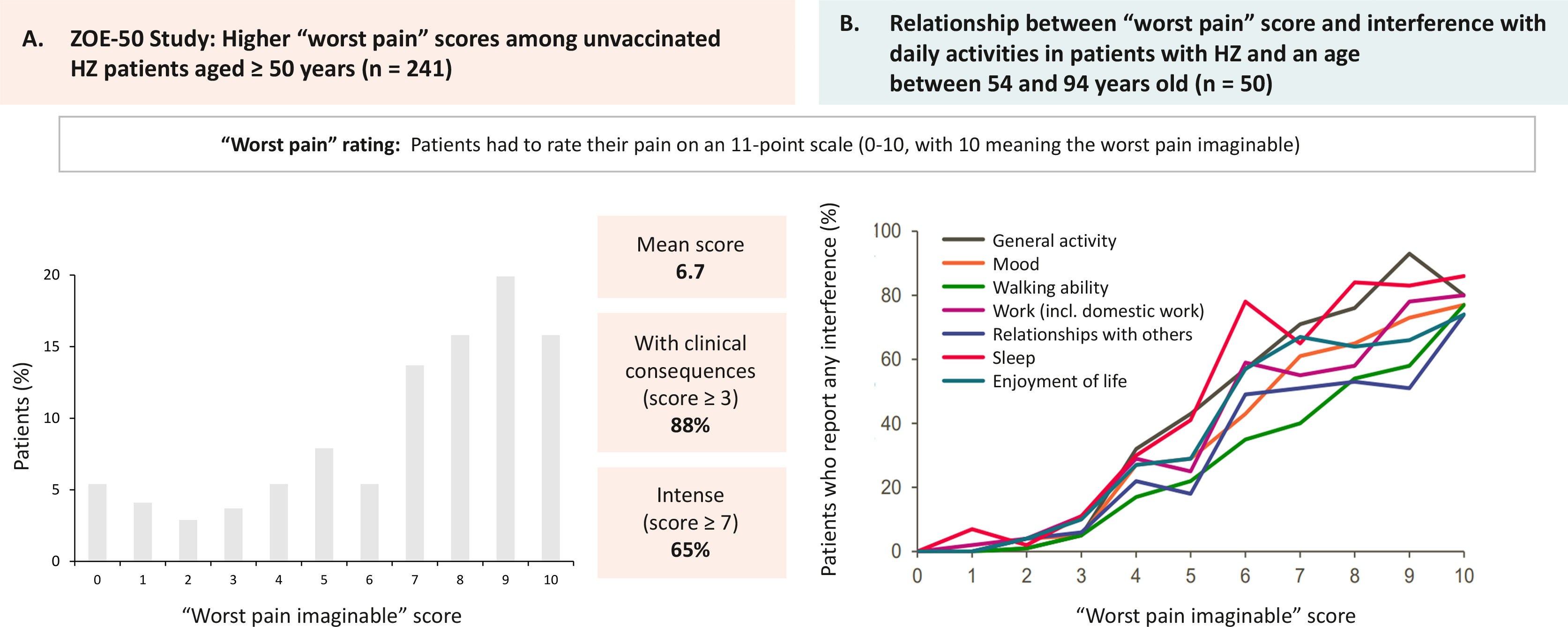

Patients and family members perceive the disease as a very disabling traumatic experience that causes suffering and interferes with their ability to live a full life (Fig. 3A).19 It can produce sleep disturbances, severe depression, and anxiety (Fig. 3B).20 The risk of anxiety and depression in patients with PHN and severe pain is greater than in patients with milder pain. Cases of suicide have even been described in some patients as a direct consequence of PHN.21 In a study conducted in Spain, 80.1% of patients with HZ reported moderate/severe pain and 46.2% reported severe pain, both on day 0, and the pain score was higher in patients who subsequently developed PHN than in those who did not have this complication.7 The risk of having severe PHN requiring hospitalisation increases with age. More than 90% of these cases occur in people over 50 years of age.2

The impact of herpes zoster (HZ) on pain and patients' quality of life.

A) ZOE-50 study. Maximum “worst pain” scores in patients aged 50 years or older with HZ and unvaccinated (n=241). Patients rated pain on a scale of 0 to 10 points (0=no pain; 10=worst pain imaginable). Figure created from results provided by Curran et al19. (B) Assessment of quality of life in patients with HZ. Relationship between the “worst pain” score and interference with daily life in patients aged between 54 and 94 years. Patients rated pain on a scale of 0–10 points (0=no pain; 10=worst pain imaginable). Figure created from results provided by Lydick et al20.

The principal goals of HZ treatment are to shorten the extent and duration of cutaneous symptoms, reduce the intensity and duration of acute pain, and reduce the intensity of PHN-associated pain. In immunocompromised patients and other vulnerable patients, the intention of treatment is to reduce the frequency and severity of complications.22

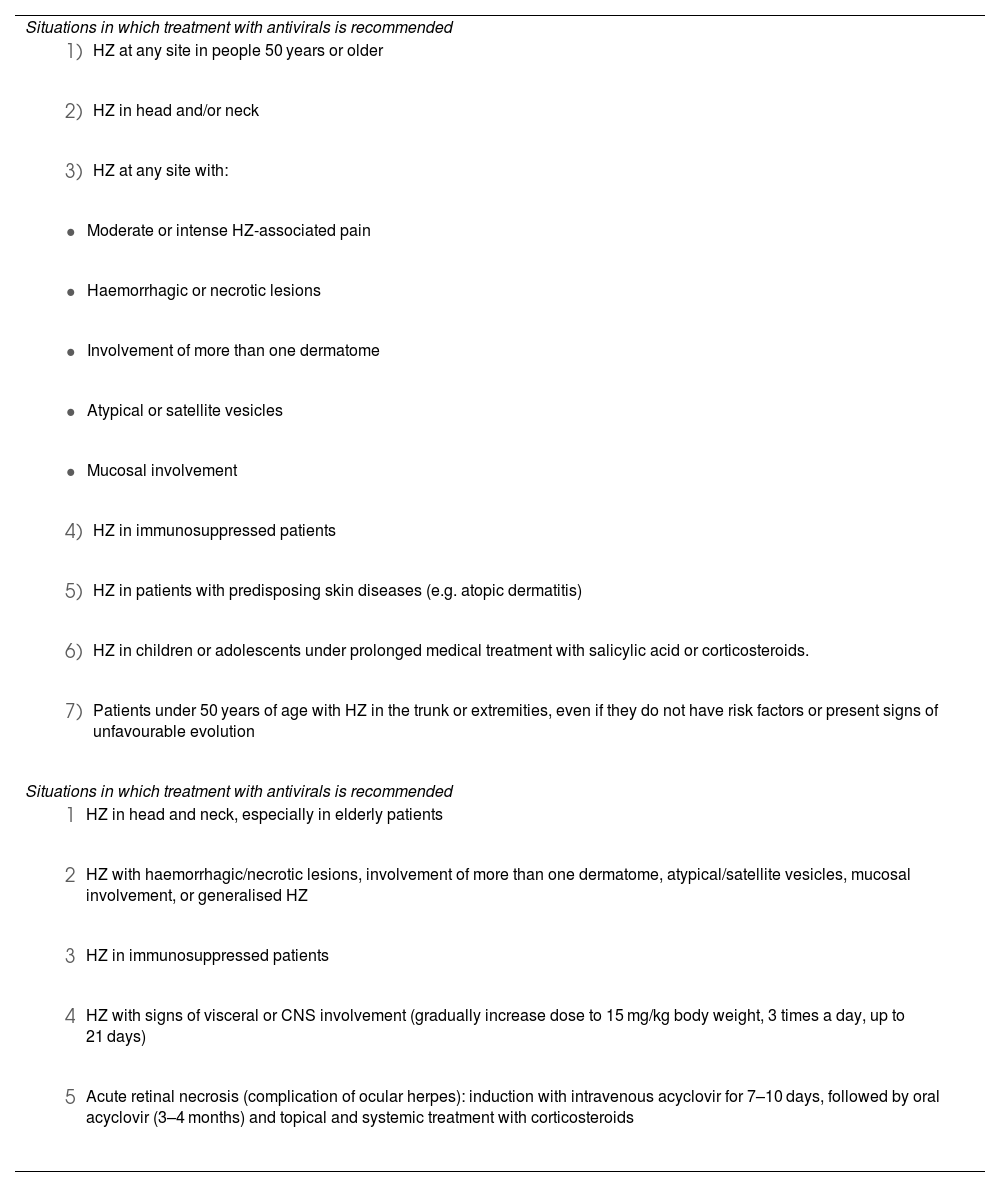

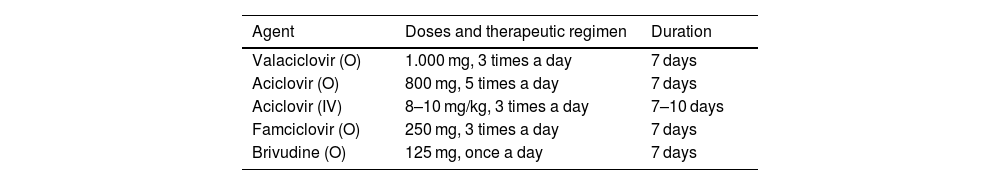

Pharmacological treatment for acute infectionThe 3 components of pharmacotherapy against acute HZ are antiviral drugs, analgesia, and local treatment with constant consideration of each patient's clinical status. Antiviral treatment is recommended when there is a higher risk of complications or sequelae (Table 1).22 There are currently 4 nucleoside analogues that are effective orally against HZ: acyclovir, valacyclovir, famciclovir, and brivudine (Table 2). However, these treatments have not yet been proven to be effective in reducing the incidence of PHN.23

Situations in which treatment with antivirals for herpes zoster is recommended.

| Situations in which treatment with antivirals is recommended |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Situations in which treatment with antivirals is recommended |

|

|

|

|

|

CNS: Central nervous system; HZ: Herpes zoster. Source: Werner et al22.

Conventional antiviral treatment for herpes zostera.

| Agent | Doses and therapeutic regimen | Duration |

|---|---|---|

| Valaciclovir (O) | 1.000 mg, 3 times a day | 7 days |

| Aciclovir (O) | 800 mg, 5 times a day | 7 days |

| Aciclovir (IV) | 8–10 mg/kg, 3 times a day | 7–10 days |

| Famciclovir (O) | 250 mg, 3 times a day | 7 days |

| Brivudine (O) | 125 mg, once a day | 7 days |

HZ: Herpes zoster; IV: Intravenous route; O: Orally.

IV acyclovir may be administered to patients with severe disease and those at high risk of complicated evolution. These drugs have been shown to reduce the duration of skin lesions, as well as have an effect on the duration and intensity of acute HZ-associated pain. No statistically significant differences were found regarding the duration of pain and skin lesions when the drugs were compared. Brivudine has fewer studies and may be more useful in patients with renal failure23.

Acute HZ-associated pain appears in more than 95% of patients over 50 years of age.23 Initially, this pain is nociceptive, but later, a neuropathic component may appear. Painkillers are used for treatment, although applying cold, wet compresses to the blisters can help relieve pain. In the absence of acute pain control, and if a neuropathic component is suspected, analgesics can be combined with anticonvulsants (gabapentin or pregabalin), tricyclic antidepressants, venlafaxine, or duloxetine as second-line treatment.23,24 It is uncommon to resort to interventional treatments for acute pain.

For ophthalmic herpes zoster, it is recommended to complement systemic treatment with topical acyclovir preparations in the affected eye.22,23 OHZ does not have a specific topical treatment.

Pharmacological treatment for chronic painPHN requires a therapeutic regimen that combines analgesics with different mechanisms of action. In the absence of control, tricyclic antidepressants are added. Although amitriptyline is the most studied for PHN, nortriptyline and desipramine have fewer anticholinergic side effects. Anticonvulsants (gabapentin and pregabalin) can also be used as first line, showing similar effects with better pharmacological tolerance. As a second-line treatment, in cases of localised pain, topical lidocaine and capsaicin patches or even the use of opioids may be recommended.23 When there is a lack of response to pharmacological treatment, interventional treatments may be used (botulinum toxin injections, epidural/intrathecal and paravertebral nerve blocks with local anaesthetics and/or corticosteroids, or spinal cord stimulation).24,25 Pharmacological treatment of PHN in elderly people who are generally polymedicated also entails a significant risk of drug interactions and adverse events of particular impact (drowsiness, dizziness, gait disorders, falls, weight gain).26

Herpes zoster vaccinesVaricella vaccines and HZ vaccines can modify the natural history of VZV infection. Vaccination against varicella is indicated to prevent primary VZV infection, and vaccination against HZ is indicated to prevent reactivation of the latent virus.2 Until now, vaccination against HZ is the only way to prevent the disease and its complications.

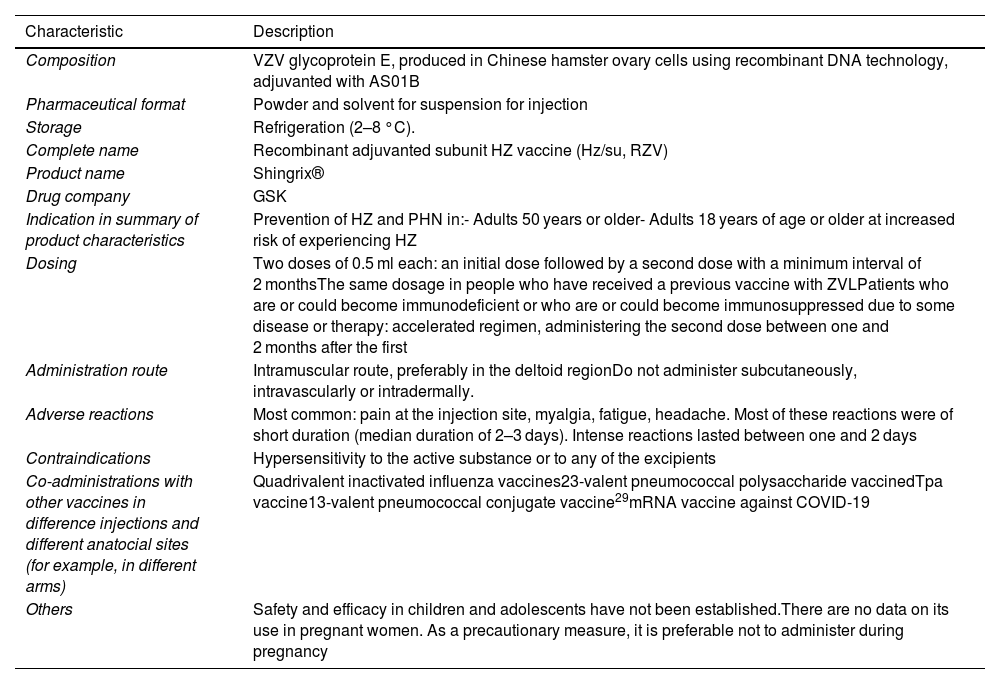

There are currently 2 authorised vaccines to prevent HZ: the live-attenuated virus vaccine for the revention of HZ (ZVL), with an antigenic load approximately 15 times higher than the vaccine against varicella, which has been available in Spain since 2014 but is no longer marketed;27 and the recombinant HZ vaccine (RZV), previously known as the HZ subunit vaccine (HZ/su), composed of VZV glycoprotein E and the AS01B adjuvant system (based on liposomes with 2 immunostimulants, monophosphoryl lipid A [MPL], and fraction 21 of Quillaja saponaria Molina [QS-21], whose synergistic effect induces a powerful and sustained humoral and cellular response), available in Spain since 2021 (Table 3). The design of this vaccine enables the induction of antigen-specific humoral and cellular immune responses in individuals with pre-existing immunity against VZV by combining the VZV-specific antigen (gE) with the AS01B28 adjuvant system.

Characteristics of the recombinant adjuvanted subunit vaccine against herpes zoster.

| Characteristic | Description |

|---|---|

| Composition | VZV glycoprotein E, produced in Chinese hamster ovary cells using recombinant DNA technology, adjuvanted with AS01B |

| Pharmaceutical format | Powder and solvent for suspension for injection |

| Storage | Refrigeration (2–8 °C). |

| Complete name | Recombinant adjuvanted subunit HZ vaccine (Hz/su, RZV) |

| Product name | Shingrix® |

| Drug company | GSK |

| Indication in summary of product characteristics | Prevention of HZ and PHN in:- Adults 50 years or older- Adults 18 years of age or older at increased risk of experiencing HZ |

| Dosing | Two doses of 0.5 ml each: an initial dose followed by a second dose with a minimum interval of 2 monthsThe same dosage in people who have received a previous vaccine with ZVLPatients who are or could become immunodeficient or who are or could become immunosuppressed due to some disease or therapy: accelerated regimen, administering the second dose between one and 2 months after the first |

| Administration route | Intramuscular route, preferably in the deltoid regionDo not administer subcutaneously, intravascularly or intradermally. |

| Adverse reactions | Most common: pain at the injection site, myalgia, fatigue, headache. Most of these reactions were of short duration (median duration of 2–3 days). Intense reactions lasted between one and 2 days |

| Contraindications | Hypersensitivity to the active substance or to any of the excipients |

| Co-administrations with other vaccines in difference injections and different anatocial sites (for example, in different arms) | Quadrivalent inactivated influenza vaccines23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccinedTpa vaccine13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine29mRNA vaccine against COVID-19 |

| Others | Safety and efficacy in children and adolescents have not been established.There are no data on its use in pregnant women. As a precautionary measure, it is preferable not to administer during pregnancy |

dTpa: diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis vaccine (acellular component) with reduced antigenic content; HZ: herpes zoster; PHN: post-herpetic neuralgia; RZV: recombinant adjuvanted subunit herpes zoster vaccine; VZV: varicella zoster virus.

Given that only RZV is marketed in Spain, only this vaccine will be described below. The RZV vaccine is indicated for the prevention of HZ and PHN in adults aged 50 years and older and also in adults aged 18 years and older at increased risk of HZ, including immunocompromised persons where the ZVL vaccine was contraindicated.28

Efficacy and effectiveness of the recombinant adjuvanted subunit herpes zoster vaccineThe 2 main randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trials that have demonstrated the efficacy of RZV are the ZOE-50 study (n=16 160; ≥50 years)30 and the ZOE-70 study (n=14 816; ≥70 years).31

The efficacy of the vaccine in healthy adults aged 50 years or older was 97.2%.30 In the pooled analysis of both studies, an efficacy against HZ of 91.3% was observed in those aged ≥70 years and an efficacy against NPH of 91.2 and 88.8% in those aged ≥50 years and ≥70 years, respectively.31 The efficacy of HZ vaccine has not been reported to be affected by the presence of comorbidities and remains in line with the data obtained in the ZOE-50 and ZOE-70 studies, varying between 84.5% and 97% depending on the underlying disease32. In clinical practice, high effectiveness has been observed in the prevention of HZ (64.1%–85.5%) and NPH (76%) in people ≥50 years of age, including very elderly people, people with autoimmune diseases or immunocompromised patients.33,34

Placebo-controlled clinical trials have also been carried out in recipients over 18 years of age of autogenous haematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) (Zoster-002; n=1846) and with malignant blood diseases (Zoster-039; n=562).28 The efficacy of RZV against HZ was 68.2% (Zoster-002) and 87.2% (Zoster-039, post hoc analysis) and against NPH it was 89.3% (Zoster-002). The efficacy against other complications was 77.8% and against hHZ-associated hospitalisations it was 84.7%.28 Likewise, immunogenicity/safety studies have been carried out in other immunocompromised groups, such as patients who received a kidney transplant (Zoster-041; n=264), with solid tumours (Zoster-028; n=237) and with HIV (Zoster-015; n=123). In all of these studies, the vaccine was shown to be immunogenic and safe for these populations.35

Long-term data (10 years) from the extension study of ZOE-50 and ZOE-70 (Zoster-049), where the immunogenicity and efficacy of RZV against HZ were evaluated after receiving 2 doses separated by 2 months, show that the sustained efficacy reached 81.6% in the 4-year period of the follow-up study, i.e. between 5.6 and 9.6 years after the start of vaccination, and 89% in the period from 1 month after the second dose up to 9.6 years of follow-up.36 Other immunogenicity studies with follow-up of up to 10 years and mathematical models indicate that the immune response could be maintained for 20 years or more.

There are limited data on the use of RZV in patients with a history of HZ, although its safety and immunogenicity in them are not questioned and, consequently, several health authorities recommend its use. However, there are variations regarding what intervals to respect for administering the vaccine.37 At the national level, the Interterritorial Council of the National Health System states that vaccination with RZV is safe at any time after having suffered HZ and recovering from the injuries (disappearance of the vesicles). Although the evidence is limited, it is recommended to delay vaccination between 6 months and a year after HZ in immunocompetent people, with the potential goal of obtaining a greater response in the medium term. However, in immunosuppressed people, and given the high risk of recurrence, vaccination can be done immediately after recovery from HZ.

At international level, the Advisory Committee on Immunisation Practices recommends vaccination with RZV when the acute phase of the HZ episode has passed and symptoms have decreased, without distinguishing between immunocompetent and immunosuppressed subjects.2,38

Furthermore, in a multicentre open clinical trial (Zoster-048) in people who were already vaccinated with ZVL and who were vaccinated with RZV, the immune response to RZV was not affected.28

Coadministration of adjuvanted recombinant subunit herpes zoster vaccine and other vaccinesBased on studies conducted and recommendations from Public Health authorities, it is considered that RZV can be administered with the non-adjuvanted inactivated seasonal influenza vaccine, the 23-valent polysaccharide pneumococcal vaccine (VNP23), the 13-valent conjugate pneumococcal vaccine (VNC13), and vaccines against diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis (dTpa).2,28 In addition, there are ongoing studies evaluating the co-administration of RZV with adjuvanted and high-load seasonal influenza vaccines and COVID-19 vaccines, and some health authorities even currently consider co-administration. Similarly, at the regional level, the health authorities of Andalusia and Catalonia include co-administration with the 20-valent pneumococcal vaccine (VNC20).39,40 Vaccines must be administered in different anatomical sites.2

Vaccine safety of adjuvanted recombinant subunit herpes zoster vaccineThe RZV vaccine is well tolerated. The main adverse events of this vaccine are local reactions at the injection site, myalgia, fatigue, and headache.28 In the first 30 days after vaccination, serious adverse events were reported in 1.1% of RZV recipients and 1.3% of placebo recipients in the total vaccinated cohort.30

Worldwide vaccination strategiesThe ZVL27 and RZV28 vaccines to prevent HZ and NPH are approved in many countries with their own vaccination strategies and recommendations (Supplementary table 2).2

In Spain, the HZ vaccination recommendations approved by the Public Health Commission indicate using the RZV vaccine in adults over 18 years of age belonging to the following risk groups: people with HSCT, solid organ transplant recipients, under treatment with anti-JAK drugs, with HIV infection, malignant haemopathies,with solid tumourss under treatment with chemotherapy, and people with a history of 2 or more episodes of HZ. Likewise, vaccination is recommended in subjects over 50 years of age undergoing treatment with other immunomodulatory or immunosuppressive drugs and systematic vaccination in the general population cohorts of 65 years of age, with the possibility of progressively capturing age cohorts between 65 and 80 years of age, starting with those aged 80.

As a result of these recommendations, the different autonomous communities establish their own vaccination strategies based on different criteria. Currently, all regions are vaccinating the 6 risk groups initially included in the 2021 HZ vaccination recommendations (people with HSCT, solid organ transplant recipients, under treatment with anti-JAK drugs, with HIV, malignant haemopathies, and solid tumours being treated with chemotherapy) and some autonomous communities such as Asturias, Cantabria, Catalonia, Valencia, and the Canary Islands include people with a history of HZ. Regarding systematic vaccination in the general population, there are differences in terms of the cohorts financed in the different autonomous communities (we recommend consulting the updated information of the different health ministries).41–58

Besides the funded age cohorts, the vaccine is available on prescription from pharmacies for the entire population for which it is indicated, in keeping with the summary of product characteristics.2 National recommendations also indicate that those who have previously received ZVL can be vaccinated with RZV provided the first dose is administered at least 5 years after ZVL, although a shorter interval (minimum of 8 weeks) may be considered in people from the age 70, or if delaying the regimen with RZV means that it is administered in periods of high immunosuppression.2

The role of primary care in herpes zoster vaccinationDespite the progress that has been made, vaccination in adults is a much less widespread practice than in the paediatric population. Although childhood vaccination is carried out systematically, adult vaccination is frequently reduced to annual flu vaccination campaigns and the administration of certain vaccines in highly specific situations. However, to this day, vaccination remains one of the most cost-effective health measures. Moreover, in adults, disease prevention through vaccines serves a dual function by reducing the disease burden and preserving patients' quality of life for longer. It is therefore important that efforts be made for its application not to be limited by age, but rather that permanent action be conceived as part of a comprehensive model, together with other health interventions, to prevent diseases and promote healthy ageing.

Although many agents are involved in adult vaccination, the role of PC professionals is essential in educating the population about the importance of preventing certain vaccine-preventable diseases, such as HZ, that can significantly impact their quality of life. Scarce knowledge or inadequate information about vaccines on the part of patients; uncertainty regarding current immunisation guidelines; frequent modifications of vaccination schedules; lack of consultation time; lack of centralised registration systems, and the pressure to achieve vaccination goals, among other aspects, are factors that hinder vaccination and are recognised by health professionals.

These factors have a more direct impact on PC professionals, who are mainly responsible for vaccinating the population. Most interventions to promote vaccination should focus on raising awareness among the population through information, education, training, and awareness. Professionals, in addition to adequate training on vaccines and training in communication skills to resolve doubts about patient immunisation, also require sufficient resources. These include consultation time; adequate information on vaccine modifications and guidelines; a helpline system through automated vaccination alerts linked to medical history, and access to a centralised national vaccination registry.

ConclusionsAlthough HZ-associated mortality and hospitalisations are generally low, the use of healthcare and economic resources is extremely high due to the high incidence of HZ and its associated complications. Age and immunocompromised situations are the main risk factors. Antivirals improve the clinical course of the acute phase but have not yet been proven to be effective in preventing complications such as PHN. At the moment, vaccination is the only way to prevent HZ and its complications, especially PHN.

In Spain, there are 2 authorised vaccines, although there is only one vaccine currently available: RZV. Published data confirm the high efficacy of RZV in the prevention of HZ and PHN, and it can be used safely in immunosuppressed patients. It is essential that PC health professionals acquire leadership in vaccination and compliance with the vaccination schedule throughout life.

FundingGlaxoSmithKline Biologicals SA funded this study/research (GSK study identifier: 214093) and was involved in all stages of conducting the study, including data analysis. GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals SA also covered all costs associated with the development and publication of this manuscript.

The authors wish to thank Ana Moreno Cerro and Fernando Sánchez Barbero PhD, on behalf of Springer Healthcare Ibérica S.L., for their help in writing this manuscript. The authors would like to thank María del Rosario Cambronero PhD (GSK) for her scientific and editorial contributions during the preparation of the manuscript. The authors also thank the Business & Decision Life Sciences platform for editorial assistance and coordination of the manuscript, on behalf of GSK.

Please cite this article as: Molero JM, Ortega J, Montoro I, McCormick N. State of the art in herpes zoster and new perspectives in its prevention. Vacunas. 2024. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vacune.2024.05.001.