Neurofibromatosis type 2 (NF2) is an infrequent autosomal dominant disease characterised by the appearance of VIII nerve schwannomas, meningiomas and ocular abnormalities. Incidence of 1:25 000 and prevalence above 1:80 000 are estimated in general. The objectives of our study were to determine current prevalence of NF2 in the Community of Cantabria and the province of Las Palmas, and its head and neck manifestations.

Material and methodsThis was a population-based, retrospective study in 3 tertiary hospitals.

ResultsThe study population showed prevalence of 1:600 000 in the Community of Cantabria and 1:280 000 in the province of Las Palmas. The most frequently diagnosed tumour was acoustic neuroma (n=15), followed by trigeminal neurinoma (n=2) and vagus (n=1).

ConclusionsCases of NF2 are infrequent in Cantabria and Las Palmas, lower than that reported in the literature. The most frequently described head and neck tumour in the literature is acoustic neuroma, followed by schwannoma of cranial nerves V and X. Other tumours such as nasal, laryngeal, chorda tympani or cranial nerve VII schwannomas are also described. The most frequent ENT manifestation is hearing loss, especially unilateral, followed by cervical mass, tinnitus and headache. Early diagnosis and multidisciplinary management in specialised centres could improve life expectancy and quality of life for these patients.

La neurofibromatosis tipo ii (NFII) es una enfermedad infrecuente de herencia autosómica dominante que se caracteriza por la aparición de schwanomas del viii par, alteraciones oculares y meningiomas. Se estima una incidencia de NFII de 1:25.000 y una prevalencia mayor de 1:80.000. Los objetivos de nuestro estudio fueron determinar la prevalencia puntual de NFII en la Comunidad de Cantabria y la provincia de Las Palmas, así como caracterizar sus manifestaciones de cabeza y cuello.

Material y métodosSe trata de un estudio poblacional, retrospectivo, en 3 hospitales de tercer nivel.

ResultadosEl estudio poblacional mostró una prevalencia puntual de 1:600.000 en la Comunidad de Cantabria y 1:280.000 en la provincia de Las Palmas. El tumour más frecuentemente diagnosticado fue el neurinoma del acústico (n=15), seguido del neurinoma del trigémino (n=2) y del vago (n=1).

ConclusionesLa NFII en Cantabria y Las Palmas es infrecuente, menor a la descrita en la literatura. El tumour de cabeza y cuello más frecuentemente descrito en la literatura es el neurinoma del acústico seguido del schwanoma del v y del x par. Están descritos aisladamente otros tumores, como el schwanoma nasal, laríngeo, de chorda timpanae o del vii par. La manifestación ORL más frecuente es la hipoacusia, sobre todo unilateral, seguida de masa cervical, acúfenos y cefalea. Un diagnóstico precoz y el manejo multidisciplinar en centros especializados podrían mejorar la esperanza y calidad de vida en estos pacientes.

Neurofibromatosis (NF) is a hereditary disease of autosomal dominant transmission. NF type I or Von Recklinghausen disease, associated to a defect in chromosome 17, is characterised by the appearance of “coffee with milk” stains, neurofibromas on the skin, hamartomas of the iris and cognitive deficit, with the appearance of vestibular neuromas being rare. NF type II (NF-II), secondary to a defect in chromosome 22, is characterised by the appearance of schwannomas of the 8th cranial nerve, as well as ocular alterations and meningiomas. Although less often that in patients with NF type I, “coffee with milk” stains and neurofibromas on the skin can appear.

The use of diagnostic criteria, specific molecular tests to identify mutations, and the development of nuclear magnetic resonance imaging (NMRI) have brought about an increase in the diagnosis of this disease. Initially, the incidence of NF-II was calculated to be 1:30 000–40 000, with approximate prevalence of 1:200 000, but recent studies estimate an incidence of 1:25 000 and prevalence greater than 1:80 000.1–3 However, there are no recent population studies that analyse the prevalence and incidence of this disease in the Spanish population.

The onset of NF-II is usually in the later years of adolescence or at the beginning of adulthood, although cases of presentation between the first year of life and the seventh decade have been described. The most common symptoms are the appearance of neurological, ocular (posterior subcapsular cataract, epiretinal membranes and retinal hamartomas) and cutaneous (intradermic plaques and subcutaneous and cutaneous tumours lesions).

Among the neurological lesions, the most characteristic are bilateral vestibular schwannomas that develop around 30 years of age (90%–95%). Initial symptoms include tinnitus, hearing loss and alterations in balance that begin insidiously; however, hearing loss may occur suddenly.4 Facial paralysis is seldom produced. If not treated, the schwannoma leads to brain compression and hydrocephaly.4

Schwannomas can also appear in other cranial nerves (24%–51%), intracranial meningiomas (45%–77%), intra- and extramedullary spinal tumours, such as astrocytoma or ependymoma (63%–90%), and peripheral mononeuropathy in the form of partially recovered facial paralysis, strabismus, or fallen foot or hand (>66%).4

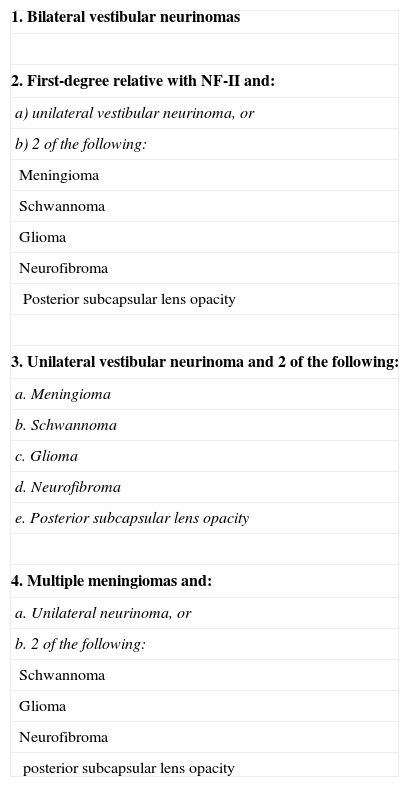

Diagnostic criteria were initially established in the conference of the National Institutes of Health Consensus in 1988.5 They were later substantially modified in the criteria of Manchester, Evans6 and Baser et al.,7 which significantly improved diagnostic sensitivity, without affecting specificity.

At present, molecular diagnosis of NF-II is carried out using the analysis of unusual mutations of the gene NF2, located in the long arm of chromosome 22 and producer of merlin or schwannomin, a membrane protein that acts as a tumour suppressor. This mutation can be found in 90% of the families with NF-II. In individuals carrying de novo mutation produced after ovular fertilisation, the existence of cell mosaicism is possible in 25%–33%, which can delay molecular diagnosis until the tumour tissue is analysed.8

Treatment for the various symptoms of NF-II is similar for sporadic tumours of the same type. However, multidisciplinary management is obligatory to minimise disabilities and to avoid morbidity secondary to treatment of these tumours.

The objectives of our study were to estimate the prevalence of NF-II in our community, as well as to characterise the symptoms of this disease in the head and neck area.

Material and MethodsEnvironment and SubjectsThis was an observational retrospective study on the population of Cantabria and the province of Las Palmas, from which we drew the patients diagnosed and in follow-up for NF-II in their corresponding centres of reference. The study involved 3 level-3 hospitals: Hospital Universitario Marqués de Valdecilla (HUMV), referral hospital in the Community of Cantabria; the Complejo Hospitalario Universitario Insular Materno Infantil (CHUIMI), referral hospital in the south of Gran Canaria island and of Fuerteventura island; and the Hospital Universitario de Gran Canaria Dr. Negrín (HUGCDN), referral hospital for the north of Gran Canaria island and Lanzarote island.

DesignThe design was retrospective observational.

InstrumentationTo perform the population study, information was gathered on the case histories of the patients with NF-II. The recompilation of the cases was carried out with the collaboration of the Coding Service in all the centres and, in the HUMV, with the additional review of the cases gathered in a specific file belonging to the Neurology Service. A total of 166 case histories (46, 34 and 86 in HUGCDN, CHUIMI and HUMV, respectively) were reviewed, with diagnoses coded as “neurofibromatosis type II”, “neurofibromatosis” and “non-specific neurofibromatosis” and the cases of NF-II were pulled. All of the patients fulfilled the diagnostic criteria for NF-II established by Evans6 in 2009 (Table 1).

Neurofibromatosis Type II Diagnostic Criteria (Including the Criteria of National Institutes of Health and Others).

| 1. Bilateral vestibular neurinomas |

| 2. First-degree relative with NF-II and: |

| a) unilateral vestibular neurinoma, or |

| b) 2 of the following: |

| Meningioma |

| Schwannoma |

| Glioma |

| Neurofibroma |

| Posterior subcapsular lens opacity |

| 3. Unilateral vestibular neurinoma and 2 of the following: |

| a. Meningioma |

| b. Schwannoma |

| c. Glioma |

| d. Neurofibroma |

| e. Posterior subcapsular lens opacity |

| 4. Multiple meningiomas and: |

| a. Unilateral neurinoma, or |

| b. 2 of the following: |

| Schwannoma |

| Glioma |

| Neurofibroma |

| posterior subcapsular lens opacity |

Source: Evans.6

Clinical and demographic variables were recorded: family history of NF-II, personal history, age at diagnosis, otorhinolaryngological (ORL) symptoms shown at any point in the disease and treatment received. The appearance of tumours in any location was documented. Treatment received was gathered distinguished between that of conservative or expectant type, unilateral or bilateral surgery unilateral or bilateral stereotactic therapy. The application of rehabilitative measures was investigated, especially those carried out on audition or facial motility. If a gene study was performed, its results were recorded.

Statistical AnalysisThe data were stored and treated using OpenOffice tools.

ResultsThe population study yielded 3 cases diagnosed and followed-up in the HUMV between January 1970 and April 2013, 2 of whom were deceased at the time of the study: the first showed disseminated NF-II with cerebral meningeal implants, implants in the left cranial nerves V and VIII and multiple intradural implants in the cervical, dorsal and lumbar regions; the patient died 11 months after the diagnosis, from severe intraventricular haemorrhage. The time and the cause of death are not documented for the second case. Considering the cases of NF-II alive at the time of the study in comparison to the reference population, NF-II prevalence in the Community of Cantabria was estimated to be 1:600 000 inhabitants.

In the HUGCDN 5 cases were recorded from 1994 to June 2013, 2 of which were deceased at the time of the study from unknown causes: clinical data could not be compiled on the first case; the second patient died at the age of 44 years, 17 years after diagnosis. In the CHUIMI there was only a single case of NF-II registered from 2005 to June 2013. Considering the NF-II cases alive at the time of our review in comparison to the population of reference, NF-II prevalence was estimated to be 1:280 000 in the province of Las Palmas.

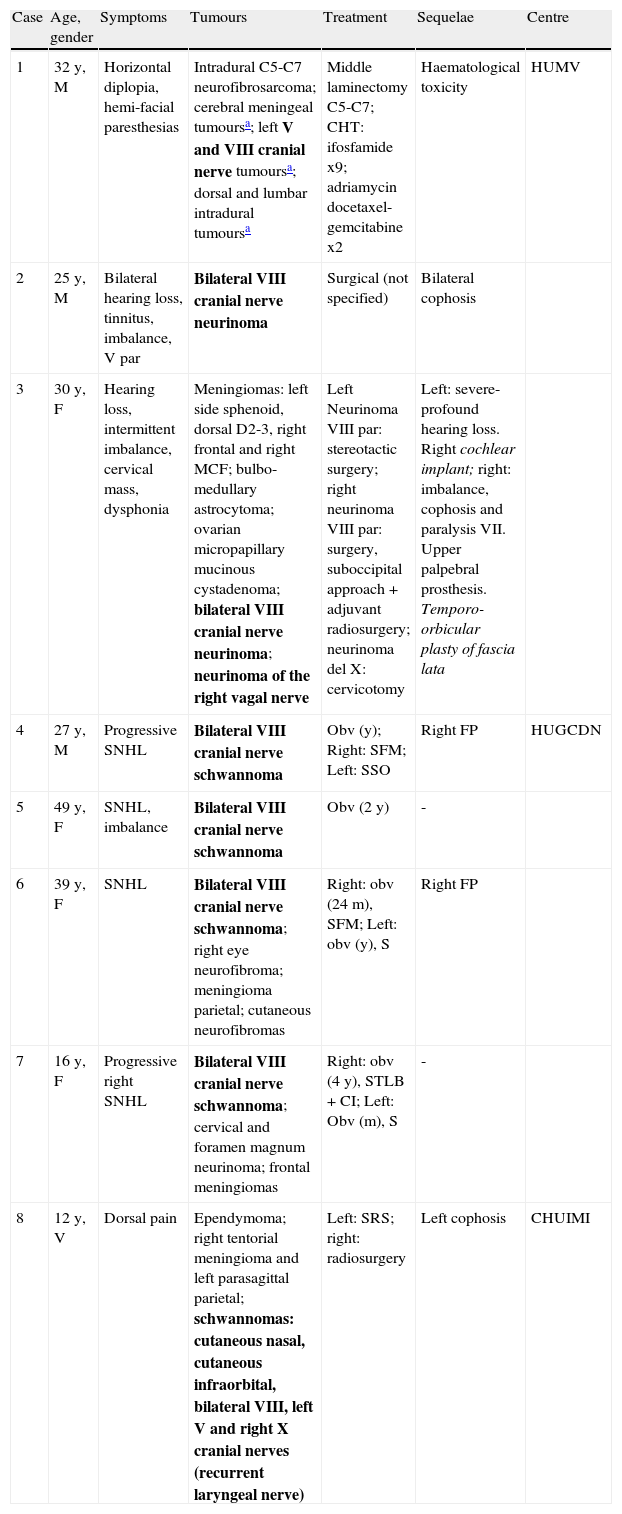

The characteristics of all the cases registered are shown summarised by hospital in Table 2.

Cases Series Presented in the Community of Cantabria and the Province of Las Palmas.

| Case | Age, gender | Symptoms | Tumours | Treatment | Sequelae | Centre |

| 1 | 32 y, M | Horizontal diplopia, hemi-facial paresthesias | Intradural C5-C7 neurofibrosarcoma; cerebral meningeal tumoursa; left V and VIII cranial nerve tumoursa; dorsal and lumbar intradural tumoursa | Middle laminectomy C5-C7; CHT: ifosfamide x9; adriamycin docetaxel-gemcitabine x2 | Haematological toxicity | HUMV |

| 2 | 25 y, M | Bilateral hearing loss, tinnitus, imbalance, V par | Bilateral VIII cranial nerve neurinoma | Surgical (not specified) | Bilateral cophosis | |

| 3 | 30 y, F | Hearing loss, intermittent imbalance, cervical mass, dysphonia | Meningiomas: left side sphenoid, dorsal D2-3, right frontal and right MCF; bulbo-medullary astrocytoma; ovarian micropapillary mucinous cystadenoma; bilateral VIII cranial nerve neurinoma; neurinoma of the right vagal nerve | Left Neurinoma VIII par: stereotactic surgery; right neurinoma VIII par: surgery, suboccipital approach+adjuvant radiosurgery; neurinoma del X: cervicotomy | Left: severe-profound hearing loss. Right cochlear implant; right: imbalance, cophosis and paralysis VII. Upper palpebral prosthesis. Temporo-orbicular plasty of fascia lata | |

| 4 | 27 y, M | Progressive SNHL | Bilateral VIII cranial nerve schwannoma | Obv (y); Right: SFM; Left: SSO | Right FP | HUGCDN |

| 5 | 49 y, F | SNHL, imbalance | Bilateral VIII cranial nerve schwannoma | Obv (2 y) | - | |

| 6 | 39 y, F | SNHL | Bilateral VIII cranial nerve schwannoma; right eye neurofibroma; meningioma parietal; cutaneous neurofibromas | Right: obv (24m), SFM; Left: obv (y), S | Right FP | |

| 7 | 16 y, F | Progressive right SNHL | Bilateral VIII cranial nerve schwannoma; cervical and foramen magnum neurinoma; frontal meningiomas | Right: obv (4y), STLB+CI; Left: Obv (m), S | - | |

| 8 | 12 y, V | Dorsal pain | Ependymoma; right tentorial meningioma and left parasagittal parietal; schwannomas: cutaneous nasal, cutaneous infraorbital, bilateral VIII, left V and right X cranial nerves (recurrent laryngeal nerve) | Left: SRS; right: radiosurgery | Left cophosis | CHUIMI |

CHT: chemotherapy; CHUIMI: Complejo Hospitalario Universitario Insular Materno Infantil; F: female; HUGCDN: Hospital Universitario de Gran Canaria Dr. Negrín; HUMV: Hospital Universitario Marqués de Valdecilla; M: male; m: months; Obv: observation; PF: facial paralysis; S: surgery not specified; SFM: surgical treatment using fossa media approach; SNHL: sensorineural hearing loss; SRS: surgical treatment using retrosigmoid approach; SSO: surgical treatment using sub-occipital approach; STLB+CI: surgical treatment using translabyrinthine approach plus cochlear implant in the same operation; y: years.

Tumours in the ORL area are indicated in bold type. The columns coloured grey show the patients deceased at the time of the study.

Family history of NF-II was only confirmed in 2 cases. In Case 8, from the CHUIMI, heterozygosis of the IVS12.2A>G mutation was found in intron 12 of the NF-II gene (22q12). This patient had a history of brain tumours of unknown origin in a grandfather and in 2 paternal great-uncles. Case 2, from the HUMV, had family history of NF-II, but a gene study was not available.

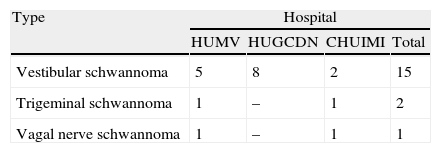

Table 3 shows a summary of the types of tumours in the ORL area presented in our series, by hospital.

Summary of the Tumours Found in our Series, Specifying Hospital of Origin.

| Type | Hospital | |||

| HUMV | HUGCDN | CHUIMI | Total | |

| Vestibular schwannoma | 5 | 8 | 2 | 15 |

| Trigeminal schwannoma | 1 | – | 1 | 2 |

| Vagal nerve schwannoma | 1 | – | 1 | 1 |

CHUIMI: Complejo Hospitalario Universitario Insular Materno Infantil; HUGCDN: Hospital Universitario de Gran Canaria Dr. Negrín; HUMV: Hospital Universitario Marqués de Valdecilla.

NF-II is a rare clinical entity. According to recent studies, incidence of 1:25 000 and prevalence greater than 1:80 000 are estimated.1–3 Prevalence in the Communities of Cantabria and the province of Las Palmas turned out to be significantly less than expected.

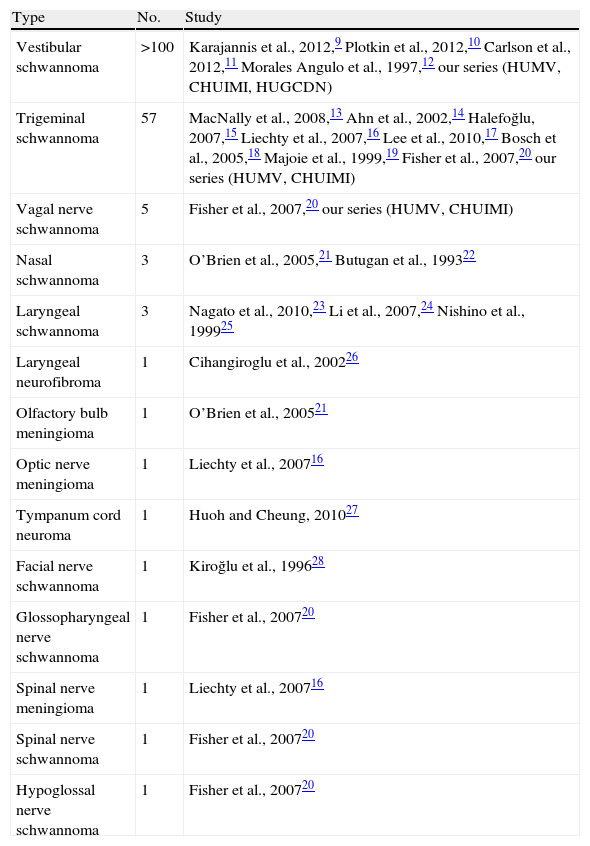

The tumours that appeared in our patients coincided with the most frequently found in the literature: based on our review, the most frequent head and neck tumour in NF-II is the acoustic neurinoma9–12 (n>100), followed by schwannoma of the V cranial nerve (n=56)13–20 and of the X nerve (n=4).20 In our series there were bilateral and unilateral cases of acoustic neurinoma (15), trigeminal nerve (2) and vagal nerve neurinoma (1). Other types of tumours in the ORL area have been described, such as nasal schwannoma21,22 and laryngeal schwannoma23–25 or neurofibroma.26 It is rare to see the appearance of other tumours such as schwannoma of the tympanic cord27 and of the facial nerve itself,28,29 as well as meningiomas of the olfactory bulb21 and of the IX,20 XI20 or XII20,30 cranial nerves. The various ORL tumours described in the literature appear summarised and by order of frequency in Table 4.

Tumours in the Otorhinolaryngological Area Described in the Literature in Patients With Neurofibromatosis Type II.

| Type | No. | Study |

| Vestibular schwannoma | >100 | Karajannis et al., 2012,9 Plotkin et al., 2012,10 Carlson et al., 2012,11 Morales Angulo et al., 1997,12 our series (HUMV, CHUIMI, HUGCDN) |

| Trigeminal schwannoma | 57 | MacNally et al., 2008,13 Ahn et al., 2002,14 Halefoğlu, 2007,15 Liechty et al., 2007,16 Lee et al., 2010,17 Bosch et al., 2005,18 Majoie et al., 1999,19 Fisher et al., 2007,20 our series (HUMV, CHUIMI) |

| Vagal nerve schwannoma | 5 | Fisher et al., 2007,20 our series (HUMV, CHUIMI) |

| Nasal schwannoma | 3 | O’Brien et al., 2005,21 Butugan et al., 199322 |

| Laryngeal schwannoma | 3 | Nagato et al., 2010,23 Li et al., 2007,24 Nishino et al., 199925 |

| Laryngeal neurofibroma | 1 | Cihangiroglu et al., 200226 |

| Olfactory bulb meningioma | 1 | O’Brien et al., 200521 |

| Optic nerve meningioma | 1 | Liechty et al., 200716 |

| Tympanum cord neuroma | 1 | Huoh and Cheung, 201027 |

| Facial nerve schwannoma | 1 | Kiroğlu et al., 199628 |

| Glossopharyngeal nerve schwannoma | 1 | Fisher et al., 200720 |

| Spinal nerve meningioma | 1 | Liechty et al., 200716 |

| Spinal nerve schwannoma | 1 | Fisher et al., 200720 |

| Hypoglossal nerve schwannoma | 1 | Fisher et al., 200720 |

CHUIMI: Complejo Hospitalario Universitario Insular Materno Infantil; HUGCDN: Hospital Universitario de Gran Canaria Dr. Negrín; HUMV: Hospital Universitario Marqués de Valdecilla.

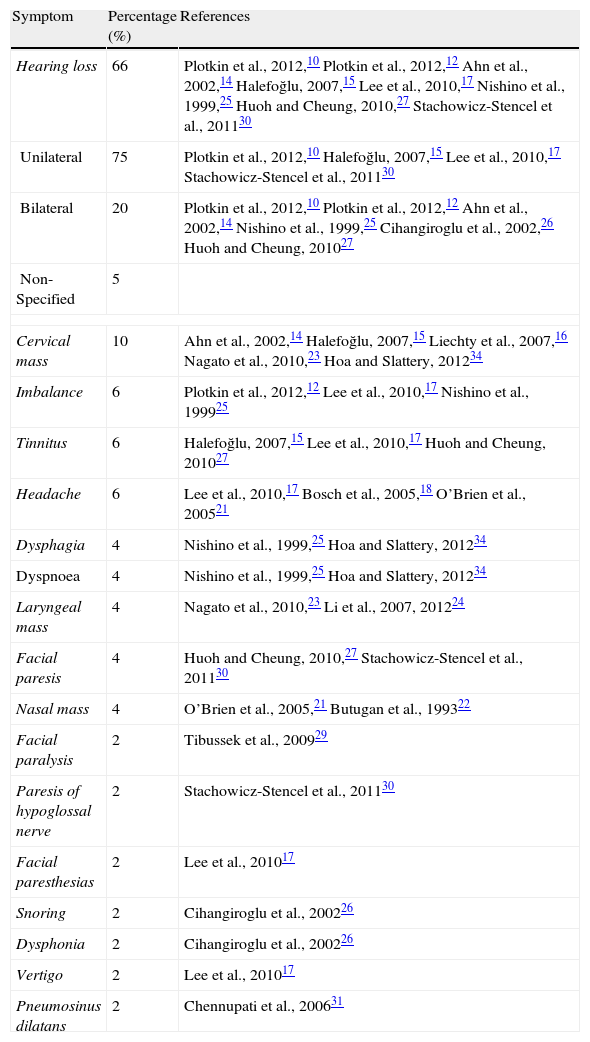

The ORL symptom most frequently reported in the literature on NF-II is hearing loss (66%)–more frequently unilateral, followed by cervical mass31 (10%), imbalance, tinnitus and headache (6%). Other less frequent symptoms are dysphagia, dyspnoea, laryngeal mass, facial paresis, nasal mass (4%) or the appearance of pneumosinus dilatans.32 The various forms of ORL presentation of NF-II described in the literature are shown ordered by frequency in Table 5.

Otorhinolaryngological Symptoms of Neurofibromatosis Type II Described in the Literature, by Frequency.

| Symptom | Percentage (%) | References |

| Hearing loss | 66 | Plotkin et al., 2012,10 Plotkin et al., 2012,12 Ahn et al., 2002,14 Halefoğlu, 2007,15 Lee et al., 2010,17 Nishino et al., 1999,25 Huoh and Cheung, 2010,27 Stachowicz-Stencel et al., 201130 |

| Unilateral | 75 | Plotkin et al., 2012,10 Halefoğlu, 2007,15 Lee et al., 2010,17 Stachowicz-Stencel et al., 201130 |

| Bilateral | 20 | Plotkin et al., 2012,10 Plotkin et al., 2012,12 Ahn et al., 2002,14 Nishino et al., 1999,25 Cihangiroglu et al., 2002,26 Huoh and Cheung, 201027 |

| Non-Specified | 5 | |

| Cervical mass | 10 | Ahn et al., 2002,14 Halefoğlu, 2007,15 Liechty et al., 2007,16 Nagato et al., 2010,23 Hoa and Slattery, 201234 |

| Imbalance | 6 | Plotkin et al., 2012,12 Lee et al., 2010,17 Nishino et al., 199925 |

| Tinnitus | 6 | Halefoğlu, 2007,15 Lee et al., 2010,17 Huoh and Cheung, 201027 |

| Headache | 6 | Lee et al., 2010,17 Bosch et al., 2005,18 O’Brien et al., 200521 |

| Dysphagia | 4 | Nishino et al., 1999,25 Hoa and Slattery, 201234 |

| Dyspnoea | 4 | Nishino et al., 1999,25 Hoa and Slattery, 201234 |

| Laryngeal mass | 4 | Nagato et al., 2010,23 Li et al., 2007, 201224 |

| Facial paresis | 4 | Huoh and Cheung, 2010,27 Stachowicz-Stencel et al., 201130 |

| Nasal mass | 4 | O’Brien et al., 2005,21 Butugan et al., 199322 |

| Facial paralysis | 2 | Tibussek et al., 200929 |

| Paresis of hypoglossal nerve | 2 | Stachowicz-Stencel et al., 201130 |

| Facial paresthesias | 2 | Lee et al., 201017 |

| Snoring | 2 | Cihangiroglu et al., 200226 |

| Dysphonia | 2 | Cihangiroglu et al., 200226 |

| Vertigo | 2 | Lee et al., 201017 |

| Pneumosinus dilatans | 2 | Chennupati et al., 200631 |

The diagnosis of schwannoma should be suspected in the presence of asymmetrical sensorineural hearing loss confirmed by liminal tone audiometry. Auditory provoked potentials can be used as an extra measure in screening, given that they would show a delay in nerve conduction on the side affected. However, the imaging test of choice is nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR), which detects tumours of up to 1mm in diameter. In this test, neurinomas appear as lesions in the region of the internal auditory canal with variable extension towards the cerebellopontine angle; they are of isointense or slightly hypointense signal in T1, hyperintense in T2 and present intense enhancement following gadolinium administration. When there is strong suspicion, gadolinium-enhanced NMR with millimetric cuts on the auditory canal axis can detect sub-millimetric tumours. In cases of intolerance or impossibility of performing a NMR, high-resolution computed tomography (CT) is an alternative.33 Patients with NF-II should also have cervical, thoracic and lumbar NMR studies to search for other tumours typical of this disease.34

NF-II is an autosomal dominant disease, with a risk of appearance in descendents of 50%. Of the patients diagnosed, 50% show a family history of NF-II and the other half are sporadic cases. The presentation form is similar among affected family members. The likelihood of NF-II in asymptomatic relatives is low; however, screening by gene study or NMR is recommended.35

The gene responsible for NF-II is located in the chromosome 22q12.2. This gene codifies a tumour suppressor protein called merlin or schwannomin, in charge of negative regulation of the production Schwann cells. Mutation of this gene predisposes to the appearance of schwannomas when a second damage is produced to the gene. Various mutations have been identified, including substitution, insertion and deletion of a single pair of bases. The most common mutation is the deletion of the gene promoter of the gene NF-II, exon 1 and intron 1, as well as complete deletions of the gene.36 In one of the cases in our series, we were able to confirm the existence of heterozygosis of the mutation IVS12.2A>G in intron 12 of the NF-II gene (22q12) in a patient with family history.

The appearance of NF-II is not limited to genetic inheritance: genetic mosaicism frequently occurs35 (in an estimated 20%–30% of patients without family history),37 in which the mutation takes place after conception, resulting in 2 genetically-different cell lines. Most of the people show a low percentage of cells affected by the mutation; consequently, its detection is impossible using a blood test and a study of the tumour tissue is needed to study the mutation responsible.35 All of the cases described in our series, except for 2, are of new appearance, without family history of NF-II.

Within the clinical picture of NF-II, vestibular schwannomas are usually those with the greatest repercussion on a patient's quality of life. Given that patients can show non-specific symptoms for a long time, the diagnosis of the disease can be delayed for several years. Mean age at diagnosis of NF-II is 25 years. These cases are generally more difficult to treat than those of sporadic appearance. This is because they are usually bilateral, histologically less vascularised and more and lobular, and are sometimes accompanied by other tumours (that can be multiple), whose treatment can cause a long-term morbidity that seriously influences patient functionality. When the vestibular tumours are small (<1.5cm), they can be completely resected, preserving hearing and function of the facial nerve; if they are large, it is often only possible to debulk the lesion, without damaging hearing or the facial nerve. However, the current trend is total extirpation together with cochlear or brain trunk implantation in the same operation. In tumours smaller than 3cm, in advanced ages, and in cases of contraindication or rejection of the surgery, a therapeutic alternative is stereotactic radiosurgery with gamma knife. The role of external radiotherapy is controversial because these patients have a greater genetic susceptibility to develop secondary malignant tumours (glioblastoma, rhabdomyosarcoma and malignant meningiomas).37 Due to the involvement of the bilateral VIII cranial nerves, the majority of the patients that undergo treatment suffer bilateral hearing loss as a sequela. In addition, alteration of balance and decrease in mobility are frequent due to the involvement of the VIII cranial nerve, vision and muscle weakness. In our series hearing was rehabilitated in 2 patients: in 1 case from the HUGCDN, with excellent audiological results, and in 1 case from the HUMV, that, in contrast, obtained scant auditory performance.

Survival of 15 years following the diagnosis has been established, at the mean age of 36 years.38–40 The 2 patients that died and are documented in our series showed a survival of 17 years and 11 months respectively.

The main prognostic factors are mean age at diagnosis, presence of intracranial meningiomas and treatment in specialised centres.8 Early diagnosis, multidisciplinary management in specialised units and improvements in treatment could increase hope and quality of life for these patients.

ConclusionNF-II is a rare clinical entity in the Community of Cantabria and la province de Las Palmas. The ORL symptom most frequently reported in the literature is unilateral hearing loss, followed by the appearance of a cervical mass and imbalance. The most frequent tumour in this disease is acoustic neurinoma; vagal nerve and trigeminal neurinomas are much rarer. Early diagnosis, multidisciplinary management in specialised units and improvements in treatment could increase hope and quality of life for these patients.

Conflict of InterestsThe authors have no conflicts of interests to declare.

We wish to thank J.A. Berciano Blanco, of the NRL service at the Hospital Universitario Marqués de Valdecilla (Santander).

Thanks also go to J.T. Quintana Perera and T. Mendoza Rodríguez, of the ORL service at the Complejo Hospitalario Universitario Insular Materno Infantil (Las Palmas de Gran Canaria).

We are also grateful to Antonio Falcón Rodríguez, of the records service at the Complejo Hospitalario Universitario Insular Materno Infantil (Las Palmas de Gran Canaria), and to A. Ramos Pérez (Las Palmas de Gran Canaria).

Please cite this article as: Guerra-Jiménez G, Camargo Camacho P, Ramos-Macías Á, Morales Angulo C. Neurofibromatosis tipo II y sus manifestaciones en cabeza y cuello: revisión bibliográfica y estudio poblacional en la Comunidad de Cantabria y la provincia de Las Palmas. Acta Otorrinolaringol Esp. 2014;65(3):148–156.