During the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, immune-mediated neurological events have been described in patients vaccinated against the virus or who have overcome the disease. Among these events is Idiopathic peripheral facial palsy or Bell’s palsy.

ObjectivesTo study the incidence of Bell's Palsy in the ENT emergency department of a tertiary hospital in Catalonia during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic.

MethodsRetrospective historical cohort comparison study of patients diagnosed with Bell's palsy between January 2018 and December 2021. Crude incidence rates were calculated as the total number of events divided by person time at risk per 100.000 person-years. Observed (2020, 2021) and historical (2018, 2019) rates were compared using standardized incidence rates with corresponding 95% confidence intervals.

ResultsOf the total number of ENT emergency department visits from 2018 to 2021 (22.658), there were 247 cases of Bell's palsy. The incidence rate of Bell's palsy in the pre-pandemic group was 12,2 and 10,9 per 100.000 person-years for 2018 and 2019, respectively. The 2020 standardized incidence rate of Bell's palsy was 0,70 [95% CI 0,49–1,01] and 1,25 [95% CI 0,93–1,67] for 2021. No significant differences were evident between the two groups.

ConclusionIn our cohort, no association was found between vaccination or COVID-19 infection and the development of Bell's Palsy.

Durante la pandemia por SARS-CoV-2 se han descrito eventos neurológicos inmunomediados en pacientes vacunados contra el virus o que han superado la enfermedad. Dentro de estos eventos se encuentra la parálisis facial periférica Idiopática o Parálisis de Bell.

ObjetivosEstudiar la incidencia de Parálisis de Bell en el servicio de urgencias de Otorrinolaringología de un hospital terciario de Cataluña durante la pandemia por SARS-CoV-2.

MétodosEstudio retrospectivo de comparación de cohortes históricas de pacientes diagnosticados de Parálisis de Bell entre enero de 2018 y diciembre de 2021. Se calcularon las tasas de incidencia brutas como el número total de eventos dividido por el tiempo de la persona en riesgo por 100.000 personas-año. Las tasas observadas (2020, 2021) e históricas (2018, 2019) se compararon utilizando índices de incidencia estandarizados con sus correspondientes intervalos de confianza del 95%.

ResultadosDel total de consultas al servicio de urgencias de ORL de 2018 a 2021 (22.658), se presentaron 247 casos de Parálisis de Bell. La tasa de incidencia de parálisis de Bell en el grupo pre-pandemia fue de 12,2 y 10,9 por 100.000 personas-año para los años 2018 y 2019, respectivamente. La tasa de incidencia estandarizada de parálisis de Bell del 2020 fue de 0,70 [IC 95% 0,49 –1,01] y de 1,25 (IC 95%: 0,93–1,67) para el 2021. No se evidenciaron diferencias significativas entre los 2 grupos.

ConclusiónEn nuestra cohorte, no se ha encontrado una asociación entre la vacunación o la infección por COVID-19 y el desarrollo de Parálisis de Bell.

Idiopathic peripheral facial palsy (IPFP) or Bell's palsy is an acute unilateral or bilateral paralysis of the seventh cranial nerve, with no clear identifiable cause and which does not affect other cranial nerves.1 It is generally transient with complete recovery rates of up to 70% at 6 months.2 It represents approximately half of the cases of peripheral facial paralysis from all causes and its annual incidence ranges between 14 and 34 cases per 100,000 inhabitants.1

Its pathogenesis is uncertain, with the most accepted theory being that it is due to inflammation and oedema of the perineurium that affects its correct functioning, observing an increase in inflammatory cells in its histology. This inflammation can be caused by different factors, the most frequent being the herpes simplex virus followed by other viruses such as: herpes zoster, cytomegalovirus, Epstein Barr, paramyxovirus, adenovirus3 and more recently SARS- CoV-2.4 Additionally, non-immune, immune-mediated, gestational and genetic inflammatory mechanisms have also been attributed as a cause of IPFP.5,6

Following the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic in 2020 and the subsequent development of vaccines in late 2020 and early 2021, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in the United States and the European Medicines Agency (EMA) in Europe identified an increase in the incidence of immune-mediated neurological events such as Bell's palsy, Guillain-Barré syndrome, venous sinus thrombosis, among others, possibly related to the primary infection or as neurological adverse events after the administration of the approved vaccines. Close pharmacovigilance was carried out during the immunisation campaigns. From that time onwards, the recommendation to continue monitoring these events gave way to the publication of multiple observational studies around the world to evaluate the association between COVID-19, anti-SARS-CoV-2 vaccination, and the development of immune-mediated neurological events.

The aim of this study is to describe the incidence of Bell's palsy in the emergency department of a tertiary hospital in Catalonia during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic.

Material and methodsStudy design and populationA retrospective study comparing historical cohorts was conducted in patients ≥18 years of age diagnosed with Bell's palsy from January 1, 2018 to December 31, 2021 in the Emergency Department of the Hospital Clínic Barcelona, which serves a population of 540,000 inhabitants.

The diagnosis of Bell's palsy was made by the on-call ENT specialist and recorded in the patient's medical history (Emergency Department discharge report). The diagnosis of Bell's palsy is made by excluding other causes that produce facial paralysis (cholesteatoma, tumor, malignancy, and Ramsay Hunt syndrome, among others).

A search was carried out of all discharge reports issued in ENT emergencies during the study period. All those that presented the diagnosis of Bell's palsy were searched. Keywords, such as: “Facial paralysis”, “Peripheral facial paralysis”, “Bell's palsy”, “Idiopathic facial paralysis”, and “idiopathic peripheral facial paralysis” were also used in the search.

Two researchers reviewed the medical records of all patients to confirm that they actually described IPFP. Once the cohort was obtained, the demographic variables were described: gender and age in decimals (calculated with the date of birth and the date of the patient's visit). The degree of facial paralysis, date of control in ENT outpatient clinics or by their local ENT were recorded, and the degree of recovery of the PFPI was recorded, classifying it as complete, partial or no recovery. The results were established for the pre-pandemic (2018–2019) and pandemic (2020–2021) groups.

The classification of the severity of the paralysis was carried out using the House-Brackmann scale7 (HB): Grade I (normal function in all territories), grade II (mild dysfunction), grade III (moderate dysfunction), grade IV (moderately severe dysfunction), grade V (severe dysfunction) and grade VI (total paralysis). Likewise, facial paralysis recovery was assessed according to this same classification after receiving outpatient steroid treatment. Complete recovery was understood to be that which presents with IPFP grade I; partial recovery as that which decreased the degree of paralysis without reaching grade I, and non-recovery as paralysis that remained at the same degree or worse than at the time of diagnosis. This observational study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Hospital Clínic de Barcelona (HCB/2022/0924).

Statistical analysisMeans and standard deviation were calculated for quantitative variables, normality was assessed with the Shapiro-Wilk test, homogeneity of variance was assessed with the Levene test, and means were compared using the Student t-test. Categorical variables are expressed as total number and percentage and were compared with the Chi-square test.

Crude incidence rates were calculated as the total number of events divided by the person's time at risk per 100,000 person-years. Historical incidence rates were estimated with the mean incidence of the pre-pandemic years (2018 and 2019). The rates observed during the period 2020–2021 (pandemic) and the historical rates (2018–2019) were compared using standardised incidence rates with their corresponding 95% confidence intervals.

All statistical tests were two-tailed and the threshold for statistical significance for all tests was p ≤ .05. Analysis was performed using STATA version 16.1 (StataCorp, TX, USA).

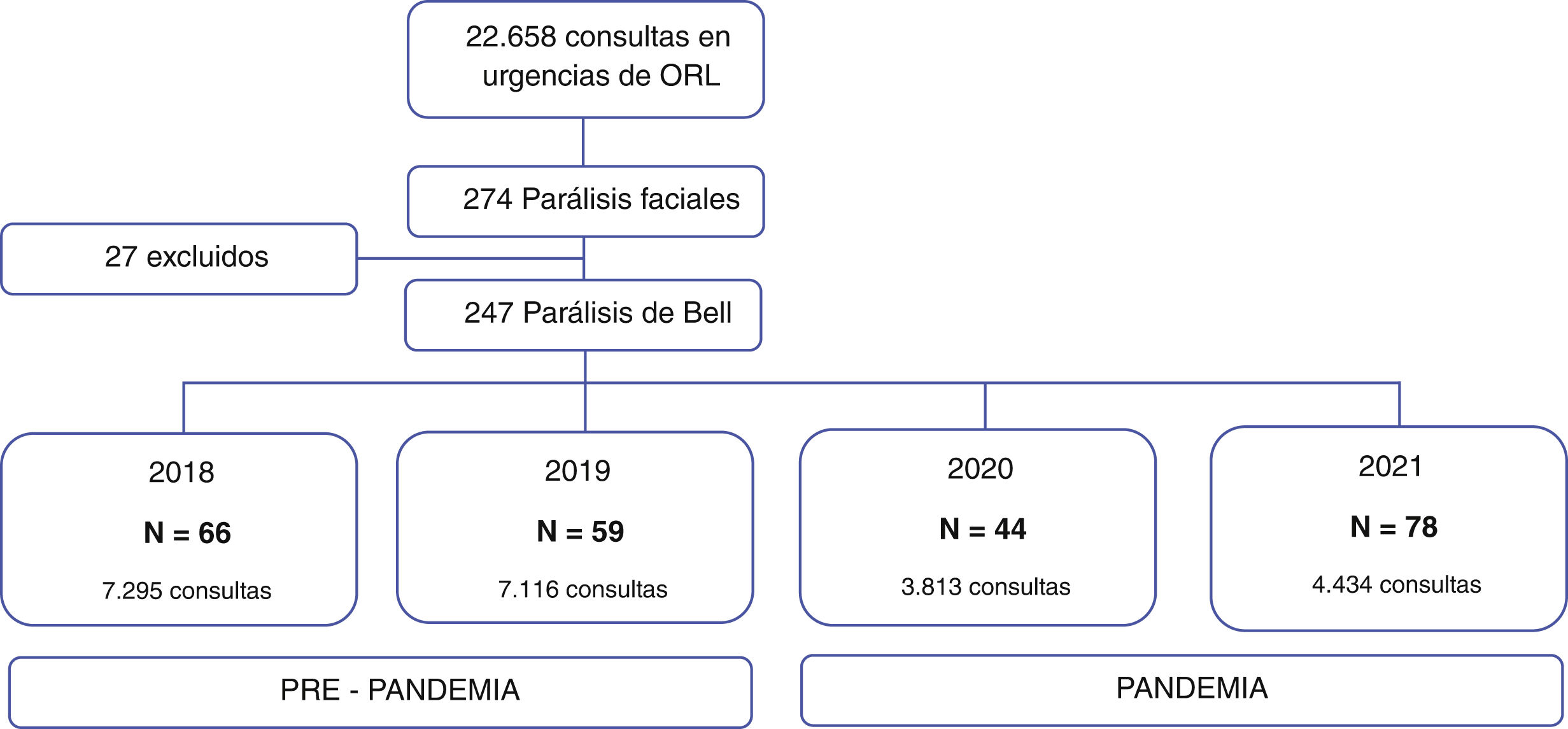

ResultsOf the total number of visits to the emergency department from 2018 to 2021 (22,658), 274 cases were consultations for facial paralysis. Of these, 27 patients with non-idiopathic peripheral facial paralysis such as: Ramsay Hunt syndrome, amyloidosis, cholesteatoma, facial neuroma, among others (Fig. 1) were excluded. The 247 cases included were classified according to the date of consultation in the pre-pandemic group 2018–2019 (n = 125) and pandemic group 2020–2021 (n = 122).

The total number of consultations in the emergency department of our hospital in the years 2018 was 7295 visits and 7116 in 2019, presenting an average of 7205 visits per year (SD = 125.6). In 2020, there was a 47.1% decrease in the number of visits (n = 3813) and in 2021, a 16.3% increase compared to 2020 (n = 4434).

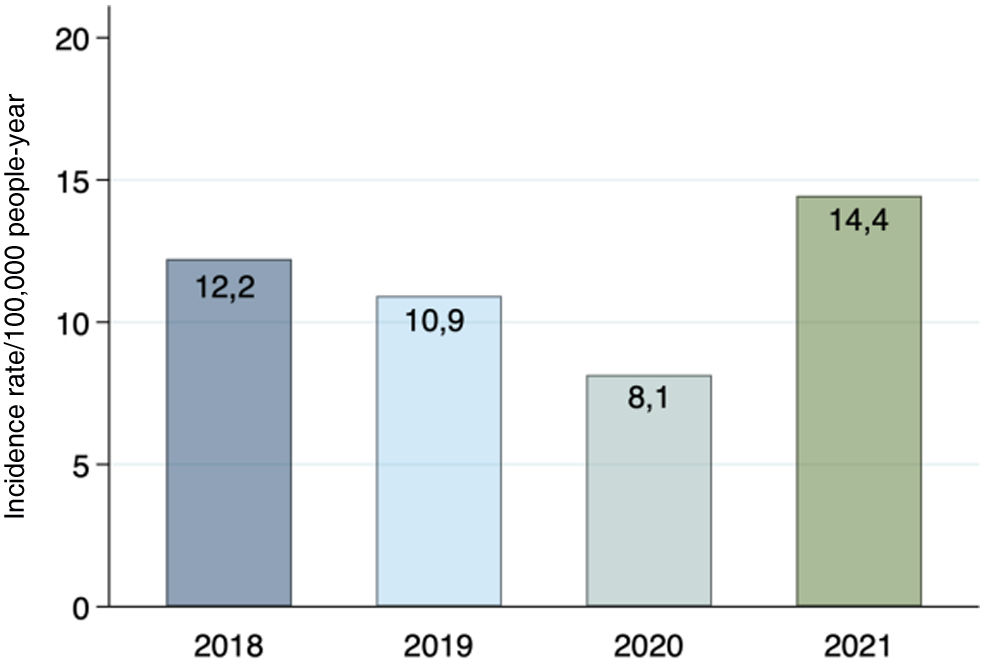

There were 66 cases of Bell's palsy in 2018, 59 in 2019, 44 in 2020, and 78 in 2021. The incidence rate of Bell's palsy in the pre-pandemic group was 12.2 and 10.9 per 100,000 people-years for the years 2018 and 2019, respectively. In the pandemic group, an incidence rate of 8.1 per 100,000 people-years was obtained in 2020 and 14.4 per 100,000 people-years in 2021. (Fig. 2).

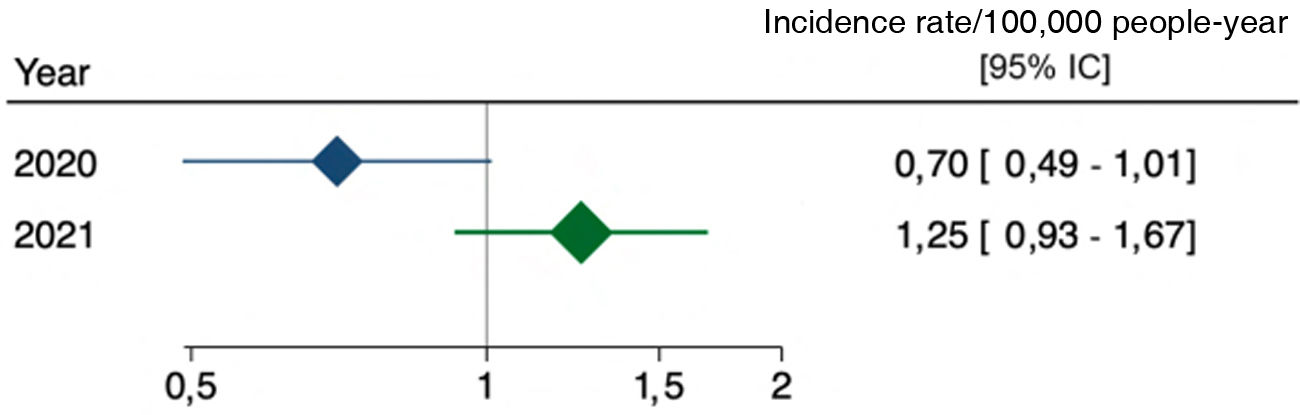

When comparing 2020 and 2021 with the incidence of previous years, the standardised incidence rate was obtained, which was .7 in 2020 [95% CI .49–1.01] and 1.25 in 2021 [95% CI .93–1.67]. The comparison with the pre-pandemic years was not statistically significant (Fig. 3).

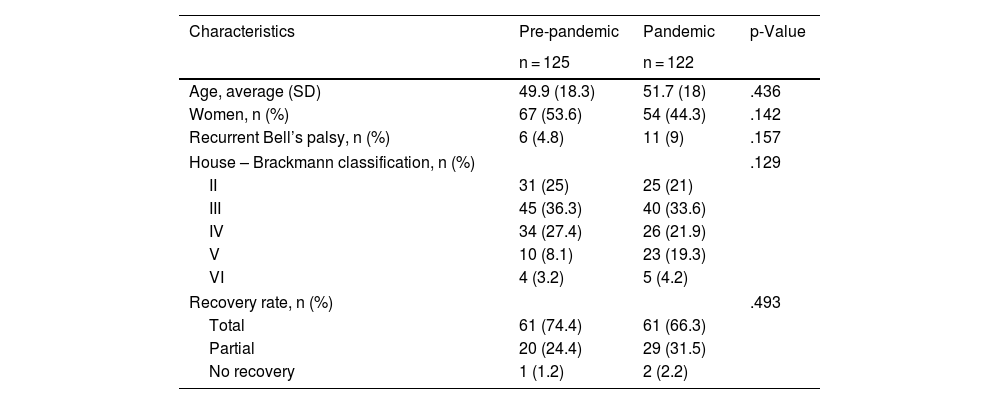

No statistically significant differences were observed between both groups for the demographic characteristics of age, gender and recurrence of facial paralysis. Most patients presented to the emergency department with grade III facial paralysis (pre-pandemic 25% and pandemic 33.6%), followed by grade IV (pre-pandemic 27% and pandemic 21.9%). The recovery rate was complete in 74.4% in the pre-pandemic group and 66.3% in the pandemic group (Table 1).

Demographic characteristics of the pre-pandemic and pandemic groups.

| Characteristics | Pre-pandemic | Pandemic | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| n = 125 | n = 122 | ||

| Age, average (SD) | 49.9 (18.3) | 51.7 (18) | .436 |

| Women, n (%) | 67 (53.6) | 54 (44.3) | .142 |

| Recurrent Bell’s palsy, n (%) | 6 (4.8) | 11 (9) | .157 |

| House – Brackmann classification, n (%) | .129 | ||

| II | 31 (25) | 25 (21) | |

| III | 45 (36.3) | 40 (33.6) | |

| IV | 34 (27.4) | 26 (21.9) | |

| V | 10 (8.1) | 23 (19.3) | |

| VI | 4 (3.2) | 5 (4.2) | |

| Recovery rate, n (%) | .493 | ||

| Total | 61 (74.4) | 61 (66.3) | |

| Partial | 20 (24.4) | 29 (31.5) | |

| No recovery | 1 (1.2) | 2 (2.2) | |

In our study, we were unable to demonstrate an association between COVID-19 infection, vaccination, and the development of PFPI. We did see a decrease in consultations for Bell's palsy in 2020 and a subsequent partial increase in 2021. These variations can be attributed to the mandatory and massive confinement that took place in Spain from March 2020 to June of the same year and to the subsequent outbreaks, which forced many people not to consult health centres in person. Furthermore, the increase in virtual care with the family doctor reduced the need for hospital care in patients with mild symptoms derived from the virus.

SARS-CoV2 infection and Bell’s paralysisLi et al.4 conducted a retrospective study comparing historical cohorts with cohorts from the UK and Spain. They collected data from CPRD (The Clinical Practice Research Datalink, UK) and SIDIAP (Information System for Research in Primary Care) and found no association between SARS-CoV-2 vaccination and the development of immune-mediated neurological events with any of the vaccines available at the time. However, the study did document a significant increase in the risk of developing PFPI, encephalomyelitis, and Guillain-Barré syndrome after SARS-CoV-2 infection, with a standardised incidence of 1.33 (1.02–1.74) in CPRD and 1.70 (1.39–2.08) in SIDIAP.

Patone et al.8 also studied a series of self-controlled cases to evaluate the association between vaccines (ChAdOx1nCoV-19 or BNT162b2) and SARS-CoV2 infection with the development of neurological complications during the vaccination administration period in England. The authors described an increased risk of developing Bell's palsy after a positive test for SARS-CoV-2.

mRNA vaccines and Bell's palsyIn May 2021, Sato at al.9 performed a disproportionality analysis of self-reported data in the US, where they identified a significant association between the administration of mRNA vaccines and the increased incidence of Bell's palsy, compared to influenza vaccination in the pre-pandemic era.

In the same year, Cirillo and Doan10 documented a 1.5–3-fold increase in the incidence of IPFP in the group of patients vaccinated with mRNA vaccines compared to the population that received traditional vaccines. Klein et al.12 conducted an interim analysis using safety and surveillance data (“Vaccine Safety Datalink”) and compared the incidence of different immune-mediated events during days 1–21 post-vaccination with mRNA vaccines with the incidence of these same events on days 22–42 post-vaccination. They found no significant differences for Bell’s palsy. The case-control study carried out in Israel by Shemer et al.13 also found no increased risk of developing IPFP post-vaccination with the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine and no significant differences in the number of consultations for Bell’s palsy compared to years prior to the pandemic. Similarly, Patone et al.8 also did not show an association between the development of facial paralysis with the mRNA vaccine BNT162b2.

Non-mRNA vaccinesPatone et al.8described an increased risk of hospital consultation on days 15–21 after the first dose with ChAdOx1nCoV-19 (AstraZeneca), without establishing a clear association with the development of IPFP. In another case series developed in Hong Kong, the risk of developing IPFP in the 42 days following vaccination with Corona-Vac was evaluated. Their findings were suggestive of an increased risk of IPFP. None of these studies were able to confirm the causal association between vaccination and the development of IPFP, and further studies on this subject are recommended.

In contrast, different publications have been consistent in stating that the number of cases of Bell's palsy post-vaccination for COVID-19 is equivalent to the number of cases after vaccination with influenza or other viral vaccines.10,11 Albakri et al.14 recently published a systematic review and meta-analysis on the development of Bell's palsy related to the administration of m-RNA and non-m-RNA vaccines. They included 52 studies and established that the rate of development of Bell's palsy was 25.3 per 1,000,000 vaccinated patients, the majority being men. This adverse effect occurred mainly after the first dose and with the administration of the Oxford/AstraZeneca vaccine.

The main limitation of our study stems from the origin of its data, which were collected in the emergency department of a tertiary-level hospital during a time period in which medical consultations were limited due to strict and massive confinement, the increase in virtual care in cases of mild illness, and the general fear of the population of going to high-risk sites of contagion. Therefore, the reduction of cases at the hospital level should not necessarily translate into a reduction in the disease, since patients who consulted in primary care in person or virtually with mild illnesses that did not require hospital intervention were not taken into account.

ConclusionsThis study does not show an association between COVID-19 infection, vaccination against SARS-CoV-2, and the development of IPFP at the hospital level in our setting. More studies are required to analyse the risk of developing IPFP based on the different strains of the virus, as well as to identify whether vaccination prevents the risk of developing neuro-immune complications in those people who have had SARS-CoV2 infection.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

FundingThis research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethical approvalApproved by the Ethics Committee of the Hospital Clínic in Barcelona (HCB/2022/0924).