We hypothesized that the recent COVID-19 pandemic may lead to a delay in renal colic patients presenting to the Emergency Department due to the fear of getting infected. This delay may lead to a more severe clinical condition at presentation with possible complications for the patients.

Material and methodsRetrospective review of data collected from three institutions from Spain and Italy. Patients who presented to Emergency Department with unilateral or bilateral renal colic caused by imaging confirmed urolithiasis during the 45 days before and after each national lockdown were included. Data collected included patients’ demographics, biochemical urine and blood tests, radiological tests, signs, symptoms and the therapeutic management. Analysis was performed between two groups, Group A: patients presenting prior to the national lockdown date; and Group B: patients presenting after the national lockdown date.

ResultsA total of 397 patients presented to Emergency Department with radiology confirmed urolithiasis and were included in the study. The number of patients presenting to Emergency Department with renal/ureteric colic was 285 (71.8%) patients in Group A and 112 (28.2%) patients in Group B (p<0.001). The number of patients reporting a delay in presentation was 135 (47.4%) in Group A and 63 (56.3%) in Group B (p=0.11). At presentation, there were no statistical differences between Group A and Group B regarding the serum creatinine level, C reactive protein, white blood cell count, fever, oliguria, flank pain and hydronephrosis. In addition, no significant differences were observed with the length of stay, Urology department admission requirement and type of therapy.

ConclusionData from our study showed a significant reduction in presentations to Emergency Department for renal colic after the lockdown in Spain and Italy. However, we did not find any significant difference with the length of stay, Urology department admission requirement and type of therapy.

Nuestra hipótesis es que la pandemia por COVID-19, y el estado de alarma impuesto por los gobiernos, pueden haber retrasado las visitas a urgencias por cólicos nefríticos, debido al miedo a contagiarse en los centros sanitarios. Este atraso en acudir a los servicios de urgencias puede llevar a un empeoramiento clínico y aumentar las complicaciones relacionadas con la enfermedad o el tratamiento recibido.

Material y métodosRealizamos una revisión retrospectiva de 3 centros hospitalarios en España e Italia. Fueron incluidos pacientes atendidos en el servicio de urgencias por cólico renal (unilateral o bilateral) secundario a litiasis confirmadas en pruebas de imagen durante los 45 días previos y posteriores a la declaración del estado de alarma de cada país. Se recolectaron datos demográficos, síntomas y signos de presentación, análisis de sangre y orina, pruebas de imagen, y manejo terapéutico. El análisis estadístico se realizó entre dos grupos, Grupo A: pacientes que acudieron antes de la declaración del estado de alarma y Grupo B: pacientes que acudieron tras la declaración del estado de alarma.

ResultadosUn total de 397 pacientes que acudieron a urgencias por cólicos nefríticos secundarios a litiasis fueron incluidos en el estudio, 285 (71,8%) en el Grupo A y 112 (28,2%) en el Grupo B (p<0,001). Un total de 135 (47,4%) en el Grupo A y 63 (56,3%) en el Grupo B (p=0,11) admitieron haber pospuesto su búsqueda de atención médica urgente. En el momento de la valoración inicial, no se encontraron diferencias entre ambos grupos en los niveles de creatinina sérica, leucocitosis, fiebre, oliguria, dolor, o hidronefrosis. Además, no se observaron diferencias en relación con la estancia media, ingreso en el servicio de urología, o necesidad de tratamientos invasivos.

ConclusiónNuestros resultados muestran una disminución significativa de atenciones en urgencias por cólicos nefríticos tras la declaración del estado de alarma en España e Italia. A diferencia de otros estudios publicados recientemente, no encontramos diferencias en la estancia media, ingreso al servicio de urología, o necesidad de tratamientos invasivos en pacientes que se presentaron antes y después del estado de alarma.

On 31st December 2019, the Wuhan Municipal Health Commission in Wuhan City, Hubei province, China reported a cluster of 27 pneumonia cases of unknown etiology.1 A novel severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-Cov-2) was identified from throat swab samples as the causative microorganism. The virus spread globally and on the 11th March 2020 the World Health Organization declared the Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) a global pandemic. Strict containment measures have been taken by governments worldwide in attempt to control the virus dissemination, ranging from school closures, social distancing to complete lockdown.2

While hospitals were overloaded with COVID-19 patients, there has been a decrease in presentation to the Emergency Department (ED) with non-severely symptomatic, or non-life-threatening conditions, such as acute uncomplicated renal colic.3–6 In the urological field, in some centers a significant reduction in access to some acute urological conditions, in particular for renal colic has been reported.7,8 While it is plausible that the lockdown may greatly decrease some pathologies such as trauma or infections, it is questionable that it can reduce the incidence of renal colic. The severity of renal colic and its associated complications vary, and ED may be presented with low-complexity cases resulting in abuse of hospital resources, that could have otherwise been managed by general practitioners. However, during the worse days of lockdown due to COVID-19 spread, there may be a worrisome delay in presentations due to patients’ fear of getting infected in hospitals.

We aim to evaluate the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the number of patients attending ED with renal colic, possible delays in presentation and the severity of clinical condition in Institutions from two of the most affected European countries, Italy and Spain. We hypothesized that the recent COVID-19 pandemic may lead to a delay in renal colic patients presenting to ED due to the fear of getting infected. This delay may lead to a more severe clinical condition at presentation with possible complications for the patients and adding further burden on the healthcare systems both in terms of costs and hospital bed occupancy. These data could be of fundamental importance for “urological counseling” in view of possible further pandemic peaks in different European countries in the coming months.

Materials and methodsStudy designAfter Institutional Review Board approval (HULP: PI-4188) data were retrospectively collected from three institutions from two European countries (Genova, Italy and Madrid and Bilbao, Spain). The study period included 45 days preceding the official date of the lockdown (9th March 2020, Italy and 13th March 2020, Spain) and 45 days following the lockdown date: Italy, from 24th January to 25th April; Spain, 28th January to 29th April.

Inclusion, exclusion criteria and collected dataPatients who presented to ED with unilateral or bilateral renal colic caused by imaging confirmed urolithiasis during the 45 days before and after each national lockdown were included. Exclusion criteria were patients with flank pain not caused by urolithiasis, patients with Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD)>grade II according to “Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes” (KIDGO) guidelines9 and patients with a solitary kidney.

Data collected included patients’ demographics, biochemical urine and blood tests (creatinine, C-Reactive Protein [CPR], Procalcitonin, white blood cell count [WBC], urinalysis), radiological tests (CT-scan; ultrasonography and abdominal X-ray), signs, symptoms, clinical parameters (temperature, urine output) and the therapeutic management (admission to the ED for less or more than 24h, admission to urology department, admission to the intensive care unit, ureteral stent placement, nephrostomy placement, ureteroscopy).

A presentation after 24h of the onset of symptoms was considered a delay. The duration of delay was estimated from the time of experiencing symptoms to the day of presentation. Where data on delay was missing, patients were phone called and asked to reply to a short interview evaluating possible delays and its causes.

Statistical analysisData were initially entered into a Microsoft Excel (Version 14.0) database and were transferred to SPSS Statistics Version 26 for analysis. The dataset was divided into two different groups: Group A, patients presenting prior to the national lockdown date, and Group B, patients presenting after the national lockdown date. Demographic and clinical characteristics were expressed as the median with interquartile range (IQR) or as a count with percentage. Continuous parametric and non-parametric data were analyzed with Student's t-test and Mann–Whitney U test respectively. Categorical variables were analyzed with Chi-squared test. All statistical tests were two sided with the significance level set at 0.05.

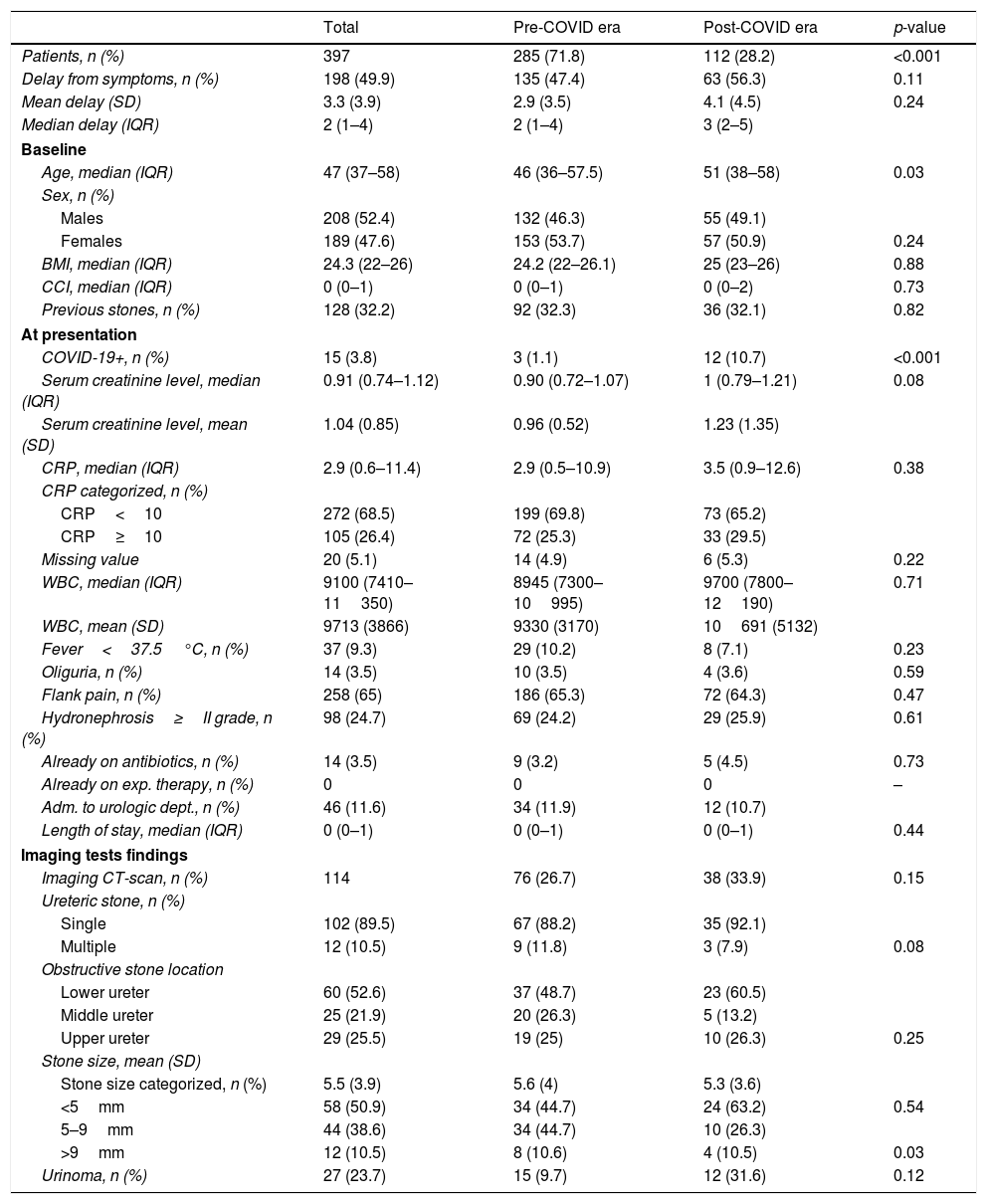

ResultsA total of 397 patients presented to ED with radiology confirmed urolithiasis and were included in the study (Table 1). The number of patients presenting to ED with renal/ureteric colic was 285 (71.8%) patients in Group A and 112 (28.2%) patients in Group B (p<0.001). The number of patients reporting a delay in presentation was 135 (47.4%) in Group A and 63 (56.3%) in Group B (p=0.11). Meanwhile the mean (SD) time of delay was 2.9 (3.5) days in Group A and 4.1 (4.5) days in Group B (p=0.24). The median age (IQR) at presentation was 46 (36.0–57.7) years and 51 (38.0–58.0) years in Group A and Group B respectively (p=0.03). The number of patients with confirmed COVID-19 was 3 (1.1%) in Group A and 12 (10.7%) in Group B (p<0.001).

Demographics, baseline biochemical and radiological findings at presentation of 397 patients attending the emergency department for renal colic.

| Total | Pre-COVID era | Post-COVID era | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients, n (%) | 397 | 285 (71.8) | 112 (28.2) | <0.001 |

| Delay from symptoms, n (%) | 198 (49.9) | 135 (47.4) | 63 (56.3) | 0.11 |

| Mean delay (SD) | 3.3 (3.9) | 2.9 (3.5) | 4.1 (4.5) | 0.24 |

| Median delay (IQR) | 2 (1–4) | 2 (1–4) | 3 (2–5) | |

| Baseline | ||||

| Age, median (IQR) | 47 (37–58) | 46 (36–57.5) | 51 (38–58) | 0.03 |

| Sex, n (%) | ||||

| Males | 208 (52.4) | 132 (46.3) | 55 (49.1) | |

| Females | 189 (47.6) | 153 (53.7) | 57 (50.9) | 0.24 |

| BMI, median (IQR) | 24.3 (22–26) | 24.2 (22–26.1) | 25 (23–26) | 0.88 |

| CCI, median (IQR) | 0 (0–1) | 0 (0–1) | 0 (0–2) | 0.73 |

| Previous stones, n (%) | 128 (32.2) | 92 (32.3) | 36 (32.1) | 0.82 |

| At presentation | ||||

| COVID-19+, n (%) | 15 (3.8) | 3 (1.1) | 12 (10.7) | <0.001 |

| Serum creatinine level, median (IQR) | 0.91 (0.74–1.12) | 0.90 (0.72–1.07) | 1 (0.79–1.21) | 0.08 |

| Serum creatinine level, mean (SD) | 1.04 (0.85) | 0.96 (0.52) | 1.23 (1.35) | |

| CRP, median (IQR) | 2.9 (0.6–11.4) | 2.9 (0.5–10.9) | 3.5 (0.9–12.6) | 0.38 |

| CRP categorized, n (%) | ||||

| CRP<10 | 272 (68.5) | 199 (69.8) | 73 (65.2) | |

| CRP≥10 | 105 (26.4) | 72 (25.3) | 33 (29.5) | |

| Missing value | 20 (5.1) | 14 (4.9) | 6 (5.3) | 0.22 |

| WBC, median (IQR) | 9100 (7410–11350) | 8945 (7300–10995) | 9700 (7800–12190) | 0.71 |

| WBC, mean (SD) | 9713 (3866) | 9330 (3170) | 10691 (5132) | |

| Fever<37.5°C, n (%) | 37 (9.3) | 29 (10.2) | 8 (7.1) | 0.23 |

| Oliguria, n (%) | 14 (3.5) | 10 (3.5) | 4 (3.6) | 0.59 |

| Flank pain, n (%) | 258 (65) | 186 (65.3) | 72 (64.3) | 0.47 |

| Hydronephrosis≥II grade, n (%) | 98 (24.7) | 69 (24.2) | 29 (25.9) | 0.61 |

| Already on antibiotics, n (%) | 14 (3.5) | 9 (3.2) | 5 (4.5) | 0.73 |

| Already on exp. therapy, n (%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | – |

| Adm. to urologic dept., n (%) | 46 (11.6) | 34 (11.9) | 12 (10.7) | |

| Length of stay, median (IQR) | 0 (0–1) | 0 (0–1) | 0 (0–1) | 0.44 |

| Imaging tests findings | ||||

| Imaging CT-scan, n (%) | 114 | 76 (26.7) | 38 (33.9) | 0.15 |

| Ureteric stone, n (%) | ||||

| Single | 102 (89.5) | 67 (88.2) | 35 (92.1) | |

| Multiple | 12 (10.5) | 9 (11.8) | 3 (7.9) | 0.08 |

| Obstructive stone location | ||||

| Lower ureter | 60 (52.6) | 37 (48.7) | 23 (60.5) | |

| Middle ureter | 25 (21.9) | 20 (26.3) | 5 (13.2) | |

| Upper ureter | 29 (25.5) | 19 (25) | 10 (26.3) | 0.25 |

| Stone size, mean (SD) | ||||

| Stone size categorized, n (%) | 5.5 (3.9) | 5.6 (4) | 5.3 (3.6) | |

| <5mm | 58 (50.9) | 34 (44.7) | 24 (63.2) | 0.54 |

| 5–9mm | 44 (38.6) | 34 (44.7) | 10 (26.3) | |

| >9mm | 12 (10.5) | 8 (10.6) | 4 (10.5) | 0.03 |

| Urinoma, n (%) | 27 (23.7) | 15 (9.7) | 12 (31.6) | 0.12 |

Legend: BMI: body mass index; CCI: Charlson comorbidity index; CRP: C reactive protein; WBC: white blood cells; IQR: interquartile range; SD: standard deviation.

No differences were found regarding the localization of the stone in the ureter and the mean stone size. The number of patients presenting with stones <5mm was 34 (44.7%) and 24 (63.2%) in Group A and Group B respectively (p<0.03).

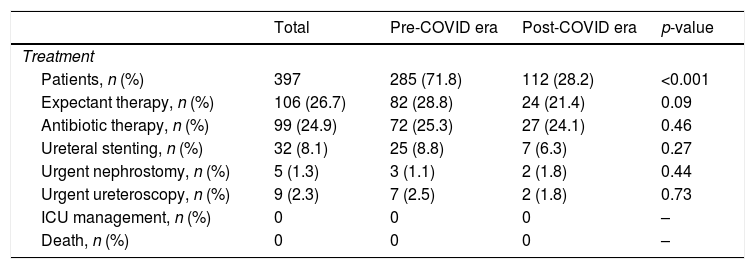

At presentation, there were no statistical differences between Group A and Group B regarding the serum creatinine level, CRP, WBC, fever, oliguria, flank pain and hydronephrosis. None of the patients were on medical expulsive therapy (MET) prior to presentation. In addition, no significant differences were observed with regards to the length of stay, Urology department admission requirement and type of therapy (ureteric stenting vs nephrostomy insertion vs MET) (Table 2).

Treatment and management of 397 patients attending the emergency department for renal colic.

| Total | Pre-COVID era | Post-COVID era | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment | ||||

| Patients, n (%) | 397 | 285 (71.8) | 112 (28.2) | <0.001 |

| Expectant therapy, n (%) | 106 (26.7) | 82 (28.8) | 24 (21.4) | 0.09 |

| Antibiotic therapy, n (%) | 99 (24.9) | 72 (25.3) | 27 (24.1) | 0.46 |

| Ureteral stenting, n (%) | 32 (8.1) | 25 (8.8) | 7 (6.3) | 0.27 |

| Urgent nephrostomy, n (%) | 5 (1.3) | 3 (1.1) | 2 (1.8) | 0.44 |

| Urgent ureteroscopy, n (%) | 9 (2.3) | 7 (2.5) | 2 (1.8) | 0.73 |

| ICU management, n (%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | – |

| Death, n (%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | – |

Legend: ICU: intensive care unit.

Here we report the incidence of urolithiasis and its associated clinical parameters at presentation and treatment outcomes 45 days before and after the date of lockdown in three major referral centers from two European countries that were severely affected by COVID-19. We hypothesized that the lockdown and COVID-19 outbreak would result in a delay presentation of renal colic possibly secondary to fear of getting infected, leading to a more severe condition and potential complications. However, in our current analysis we did not identify any significant delays in presentation and the clinical outcome did not differ between the 45-day period before and after the lockdown date. We observed a decrease in number of ED presentations following lockdown, 112 (28.2%) versus 285 (71.8%) prior to lockdown. The reduction in urolithiasis in the COVID-19 period was also observed in Antonucci et al.’s study8 which compared the number of ED admission in Rome between March and April 2020 with the same period in 2019 and identified a 48.8% reduction. Fear of acquiring COVID-19 is considered one of the key factors for avoiding or delaying ED visits.6,10 Another explanation could be that patients contacted emergency medical services via telephone, and due to the overloaded ambulance and ED services, patients were advised to stay home with over the counter analgesics and only attending ED if they presented with fever or uncontrolled pain.11–14

More patients delayed their presentation during the COVID-19 era (Group B), 56.3% versus 47.4% (Group A), but this did not reach statistical significance. A reason why a delay in presentation was not observed in this cohort of patients is possibly due to the nature of renal colic. Renal colic can cause immense pain, described as worse than childbirth15 and may be difficult to tolerate.

The presenting age was significantly higher in the post lockdown group which could be explained with fear of having a more serious condition and a lower pain threshold in older patients. There were no statistical differences in presenting clinical parameters including signs and symptoms, vitals, WBC, CRP, serum creatinine levels, stone location, hydronephrosis. In addition, the surgical intervention and type of intervention such as ureteric stenting, nephrostomy insertion or primary ureteroscopy did not differ amongst the two groups. Our finding is different to Antonucci et al.,8 who showed that the patients admitted to ED between March and April 2020 had more complications, more frequently needing hospitalization and early stone removal was preferred over urinary drainage compared with the same period in 2019. This could be explained by the different time periods studied. We compared 45 days before and after the lockdown date during the COVID-19 outbreak, whilst Antonucci et al.8 compared a non-pandemic period in 2019 with the peak time of the outbreak in Italy. Our results are more consistent with Flammia et al.16 who reported their experience with diagnostic and therapeutic procedures for urinary stones during the outbreak in March-April 2020 and the same period in 2019. They showed no significant differences detected in terms of complication rates, urinary stone size, grade of hydronephrosis and intervention rate and type of intervention (nephrostomy or ureteric stenting).16

We identified more COVID-19 positive patients in the post-lockdown group and this might be due to the increase in swab tests performed. In particular, swab testing in ED was mandatory in Italy and Spain shortly after lockdown.

Whilst most if not all European countries have got COVID-19 under control and have derived triaging, personal protective equipment and redeployment protocols to manage the disease,17 we are in a better more experienced position to tackle a second outbreak if this were to occur. However, to prevent unnecessary admission utilizing hospital resources and exposing patients to the risk of COVID-19, treatment can be delayed for asymptomatic and non-obstructing stones, and emergency interventions reserved for septic patients, solitary kidneys and obstructing stones.18

The potential limitation of our study is the relatively low number of patients. This could be expected because the three centers involved in this study were greatly impacted by the high number of COVID-19 patients that reduced the overall number of ED admissions.

ConclusionsData from our study showed a significant reduction of presentations to ED for renal colic after the lockdown in Spain and Italy. Patients’ fear to get infected, telematic triage and further public health plans may be responsible for this trend. However, we did not identify any significant difference with the length of stay, Urology department admission requirement and type of therapy.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Please cite this article as: Carrion DM, Mantica G, Antón-Juanilla M M, Pang KH, Tappero S, Rodriguez-Serrano A, et al. Evaluación de las tendencias y presentación clínica de pacientes con cólico nefrítico que acuden al servicio de urgencias durante la era pandémica del COVID-19. Actas Urol Esp. 2020;44:653–658.