The COVID-19 outbreak has substantially altered residents’ training activities.

While several new virtual learning programs have been recently implemented, the perspective of urology trainees regarding their usefulness still needs to be investigated.

MethodsA cross-sectional, 30-item, web-based Survey was conducted through Twitter from April 4th, 2020 to April 18th, 2020, aiming to evaluate the urology residents’ perspective on smart learning (SL) modalities (pre-recorded videos, webinars, podcasts, and social media [SoMe]), and contents (frontal lessons, clinical case discussions, updates on Guidelines and on clinical trials, surgical videos, Journal Clubs, and seminars on leadership and non-technical skills).

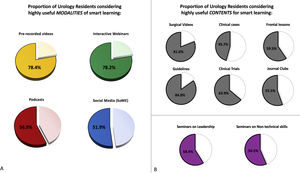

ResultsOverall, 501 urology residents from 58 countries completed the survey. Of these, 78.4, 78.2, 56.9 and 51.9% of them considered pre-recorded videos, interactive webinars, podcasts and SoMe highly useful modalities of smart learning, respectively. The contents considered as highly useful by the greatest proportion of residents were updates on guidelines (84.8%) and surgical videos (81.0%). In addition, 58.9 and 56.5% of responders deemed seminars on leadership and on non-technical skills highly useful smart learning contents.

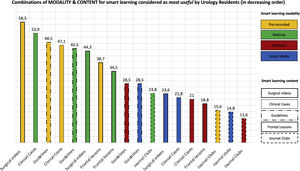

The three preferred combinations of smart learning modality and content were: pre-recorded surgical videos, interactive webinars on clinical cases, and pre-recorded videos on guidelines.

ConclusionOur study provides the first global “big picture” of the smart learning modalities and contents that should be prioritized to optimize virtual Urology education. While this survey was conducted during the COVID-19 outbreak, our findings might have even more impact in the future.

La pandemia de la COVID-19 ha alterado sustancialmente las actividades de formación de los residentes.

Si bien recientemente se han implementado nuevos programas de aprendizaje virtual, aún debe investigarse su utilidad desde la perspectiva de los aprendices de urología.

MétodosEncuesta online transversal de 30 ítems, distribuida a través de Twitter, entre el 4 y el 18 de abril de 2020, con el objetivo de evaluar la perspectiva de los residentes de urología sobre las modalidades (videos pregrabados, seminarios web, podcasts y redes sociales [RRSS]) y contenidos (lecciones frontales, discusiones de casos clínicos, actualizaciones sobre guías y ensayos clínicos, videos quirúrgicos, clubes de revistas y seminarios sobre liderazgo y habilidades no técnicas) del aprendizaje inteligente (Smart learning).

ResultadosEn total, 501 residentes de urología de 58 países completaron la encuesta. De estos, 78,4, 78,2, 56,9 y 51,9% consideraron los videos pregrabados, seminarios web interactivos, podcasts y RRSS, respectivamente, como modalidades de aprendizaje inteligente muy útiles. Los contenidos considerados como muy útiles por la mayor proporción de residentes fueron las actualizaciones de guías clínicas (84,8%) y videos quirúrgicos (81,0%). Además, más de la mitad de los residentes consideraron los seminarios de liderazgo y los de habilidades no técnicas (58,9 y 56,5%, respectivamente) como contenidos útiles para el aprendizaje inteligente.

Las tres combinaciones preferidas de modalidad y contenido de aprendizaje inteligente fueron: videos quirúrgicos pregrabados, seminarios web interactivos sobre casos clínicos y videos pregrabados sobre guías.

ConclusiónNuestro estudio proporciona la primera «visión global» de las modalidades y contenidos de aprendizaje inteligente que deben priorizarse con el objetivo de optimizar la educación virtual en urología. Aunque este estudio se llevó a cabo durante la pandemia de la COVID-19, nuestros hallazgos podrían tener un impacto aún mayor en el futuro.

The COVID-19 outbreak has caused major changes in Urological practice1–3 and has substantially compromised the exposure of urology residents to both clinical and surgical activities,4 leading to a slowdown of their learning and training experience.5,6 As such, to facilitate continuity of Urology education during such an emergency, it became necessary to implement alternative teaching methods using smart technologies.5

Notably, this unprecedented scenario has offered the opportunity to explore the preferences and perspectives of residents on both the modalities and contents of such smart learning tools, with the aim to optimize transmission of knowledge in the future, beyond the current pandemic.

While several pioneering virtual learning programs have been recently developed in response to the COVID-19 pandemic (such as the Urology 60 Minutes by the University of Southern California,7 the Urology COViD lecture series by the University of California San Francisco,8 and the Educational Multi-institutional Program for Instructing REsidents (EMPIRE) Urology lecture series by the New York AUA9) to meet the need of education overcoming the barriers of social-distancing, the perspective of urology residents (the target audience for such programs) regarding their usefulness still needs to be investigated.

In this study we aimed at providing a global overview from Urology residents worldwide on such technologies for education purposes.

MethodsSurvey's design and dissemination channelsA cross-sectional, 30-item, web-based Survey was developed using Google Forms (in both the English and Chinese languages) according to the Checklist for Reporting Results of Internet E-Surveys (CHERRIES) (Appendix A).10

Following an initial pilot assessment and obtained IRB approval, residents were invited to participate in the anonymous survey through Twitter from April 4th, 2020 to April 18th, 2020. The ESRU's official mailing list including each European Country's National Communication Officer was also used to spread the survey across European residents.

Organizations engaged in the field of urology including the Italian Society of Urology (SIU), the European Association of Urology (EAU), the European Society of Residents in Urology (ESRU), the EAU Young Academics Urologists (EAU-YAU), the EAU Section of Urotechnology (ESUT), the Asian Urological Training and Education Group (AUSTEG), the AFUF (Association Francaise des Urologues en Formation), the Spanish Urology Residents Working Group (RAEU), the German Society of Residents in Urology (GeSRU), the Young Urologic Oncologist Section of the Society of Urologic Oncology (SUO), the University of California San Francisco (UCSF), UroSoMe and UroToday, helped disseminating the survey through their Twitter accounts. In addition, the survey was advertised through the Urology COViD lecture series website of the UCSF (https://urologycovid.ucsf.edu).

Two reminders were sent via Twitter three and eleven days after the first invitation, respectively.

Participants were implied to have consented to participate upon registration. We implemented measures on IP restriction, i.e. one IP address can only complete the survey once.

The objective of the survey was to evaluate the residents’ perspective on smart learning modalities (pre-recorded videos, webinars, podcasts, and social media [SoMe]), and smart learning contents (frontal lessons [i.e. didactic lectures on urological topics], clinical case discussions, updates on Guidelines and on clinical trials, surgical videos, and Journal Clubs), both graded using a 5-tiered Likert scale. Modalities and contents scored as 4 or 5 were considered as highly useful.11 Finally, residents were asked to provide insight on the potential educational value of seminars on leadership and non-technical skills.12

The participant responses were accrued through the Google Forms website and were only accessible by the principal investigators.

Collected data on responders included: country, city, centre of training, age, gender, year of residency, previous fellowship abroad, involvement in clinical/basic urological research, use of SoMe for academic purposes, number of hours per day to dedicate to smart learning activities, current availability of smart learning programs provided by the Centre or Residency School, and potential use of other sources for smart learning.

Data analysisDescriptive statistics were reported as the median and IQR for continuous variables, and the frequency and proportion for categorical variables, as appropriate. Potential differences in baseline characteristics of residents considering each smart learning modality and content as not useful vs. highly useful were evaluated by the Pearson chi-square test.

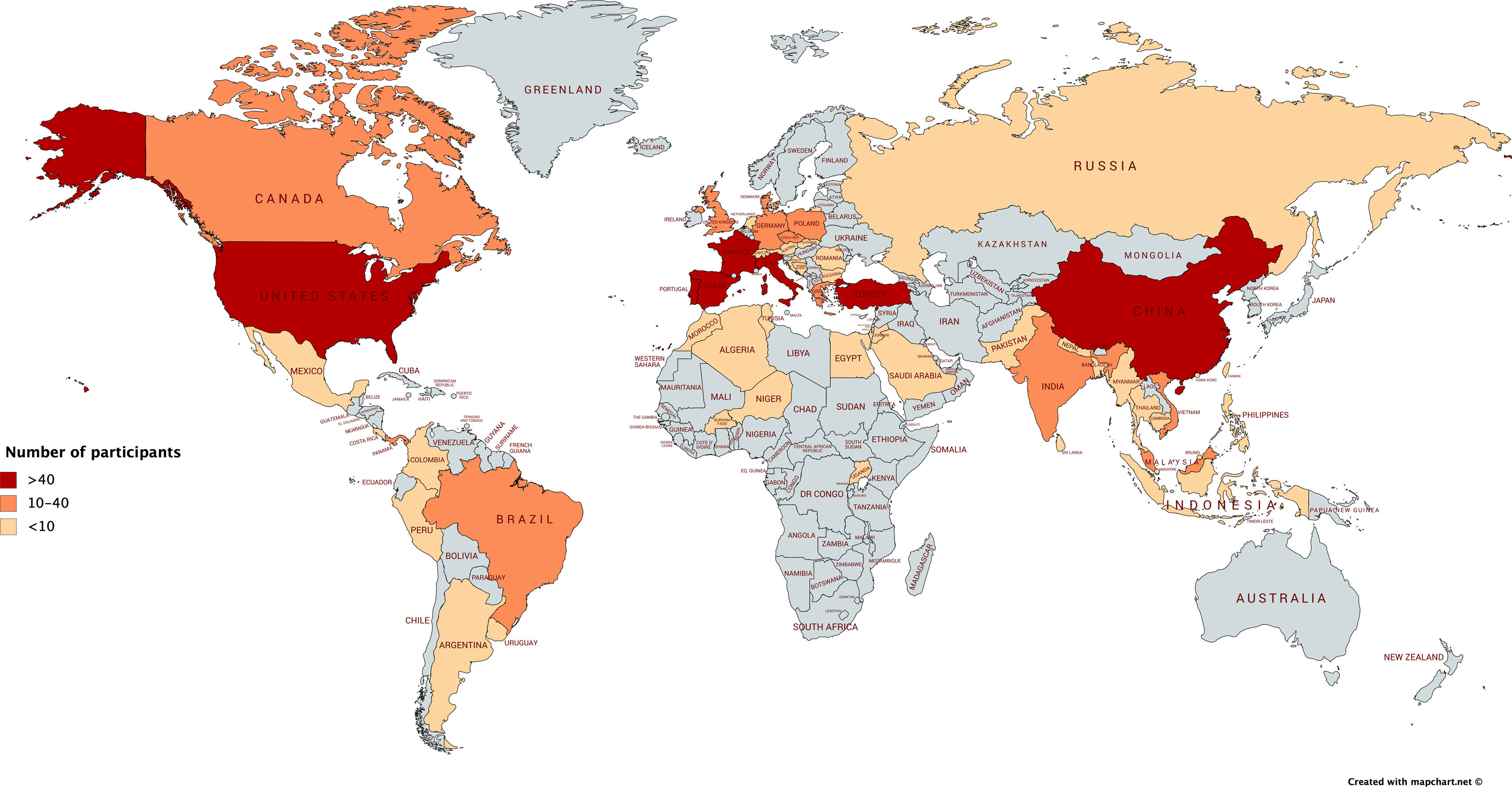

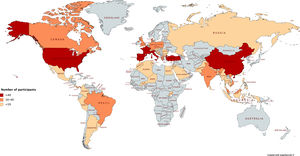

ResultsOverall, 511 urology residents from 58 Countries around the world participated in the survey (Fig. 1). We received 501 (98%) responses, representing the analytic cohort.

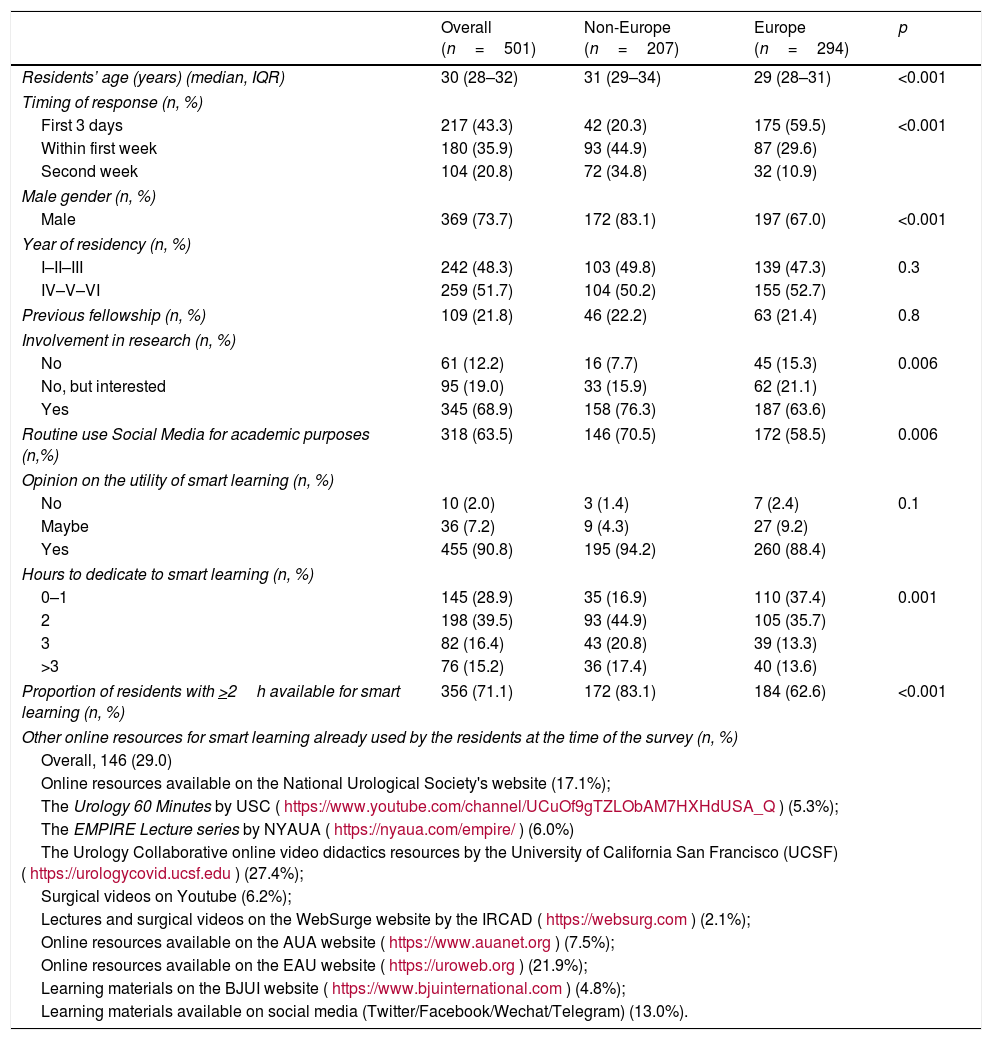

The baseline characteristics of the participants are shown in Table 1; 79.2% of them completed the survey within seven days since its launch, with no evidence of late responder bias. Overall, 58.7% were undergoing training in European countries. Median responder age was 30 years (IQR 28–32). The proportion of residents actively involved in urological research and using SoMe for academic purposes was 68.9% and 63.5%, respectively; 21.8% of responders had also pursued a research fellowship abroad. Lastly, 356 (71.1%) were spending >2h/day dedicated to smart learning activities.

Baseline characteristics of residents participating in the survey, stratified by Continent (Europe vs non-Europe).

| Overall (n=501) | Non-Europe (n=207) | Europe (n=294) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Residents’ age (years) (median, IQR) | 30 (28–32) | 31 (29–34) | 29 (28–31) | <0.001 |

| Timing of response (n, %) | ||||

| First 3 days | 217 (43.3) | 42 (20.3) | 175 (59.5) | <0.001 |

| Within first week | 180 (35.9) | 93 (44.9) | 87 (29.6) | |

| Second week | 104 (20.8) | 72 (34.8) | 32 (10.9) | |

| Male gender (n, %) | ||||

| Male | 369 (73.7) | 172 (83.1) | 197 (67.0) | <0.001 |

| Year of residency (n, %) | ||||

| I–II–III | 242 (48.3) | 103 (49.8) | 139 (47.3) | 0.3 |

| IV–V–VI | 259 (51.7) | 104 (50.2) | 155 (52.7) | |

| Previous fellowship (n, %) | 109 (21.8) | 46 (22.2) | 63 (21.4) | 0.8 |

| Involvement in research (n, %) | ||||

| No | 61 (12.2) | 16 (7.7) | 45 (15.3) | 0.006 |

| No, but interested | 95 (19.0) | 33 (15.9) | 62 (21.1) | |

| Yes | 345 (68.9) | 158 (76.3) | 187 (63.6) | |

| Routine use Social Media for academic purposes (n,%) | 318 (63.5) | 146 (70.5) | 172 (58.5) | 0.006 |

| Opinion on the utility of smart learning (n, %) | ||||

| No | 10 (2.0) | 3 (1.4) | 7 (2.4) | 0.1 |

| Maybe | 36 (7.2) | 9 (4.3) | 27 (9.2) | |

| Yes | 455 (90.8) | 195 (94.2) | 260 (88.4) | |

| Hours to dedicate to smart learning (n, %) | ||||

| 0–1 | 145 (28.9) | 35 (16.9) | 110 (37.4) | 0.001 |

| 2 | 198 (39.5) | 93 (44.9) | 105 (35.7) | |

| 3 | 82 (16.4) | 43 (20.8) | 39 (13.3) | |

| >3 | 76 (15.2) | 36 (17.4) | 40 (13.6) | |

| Proportion of residents with >2h available for smart learning (n, %) | 356 (71.1) | 172 (83.1) | 184 (62.6) | <0.001 |

| Other online resources for smart learning already used by the residents at the time of the survey (n, %) | ||||

| Overall, 146 (29.0) | ||||

| Online resources available on the National Urological Society's website (17.1%); | ||||

| The Urology 60 Minutes by USC (https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCuOf9gTZLObAM7HXHdUSA_Q) (5.3%); | ||||

| The EMPIRE Lecture series by NYAUA (https://nyaua.com/empire/) (6.0%) | ||||

| The Urology Collaborative online video didactics resources by the University of California San Francisco (UCSF) (https://urologycovid.ucsf.edu) (27.4%); | ||||

| Surgical videos on Youtube (6.2%); | ||||

| Lectures and surgical videos on the WebSurge website by the IRCAD (https://websurg.com) (2.1%); | ||||

| Online resources available on the AUA website (https://www.auanet.org) (7.5%); | ||||

| Online resources available on the EAU website (https://uroweb.org) (21.9%); | ||||

| Learning materials on the BJUI website (https://www.bjuinternational.com) (4.8%); | ||||

| Learning materials available on social media (Twitter/Facebook/Wechat/Telegram) (13.0%). | ||||

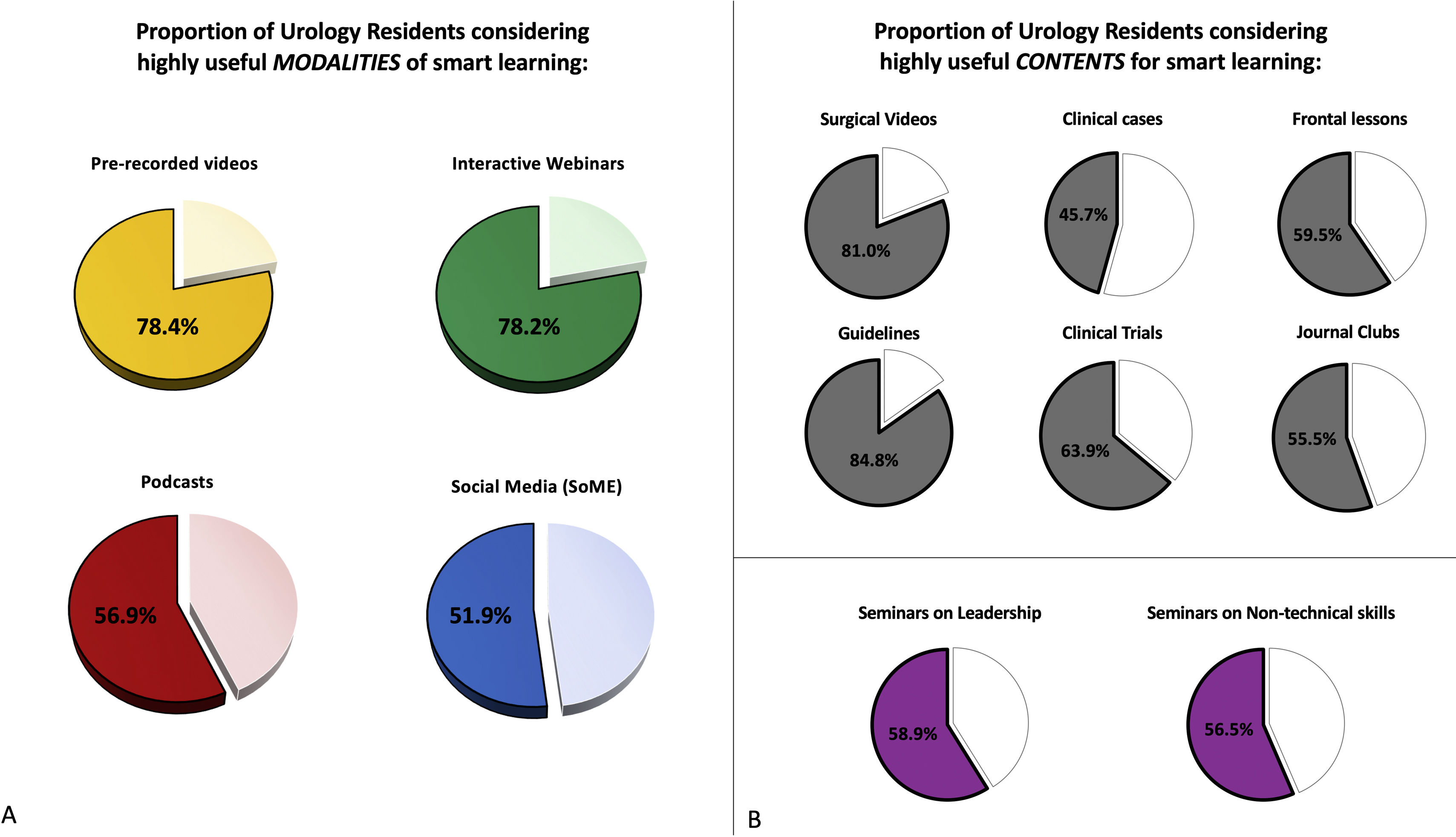

Overall, 78.4%, 78.2%, 56.9% and 51.9% of urology residents considered pre-recorded videos, interactive webinars, podcasts and SoMe, as highly useful modalities of smart learning respectively (Fig. 2A). Regarding the smart learning contents, the greatest proportion of residents considered both updates on guidelines (84.8%) and surgical videos (81.0%) highly useful; this proportion was 63.9% for updates on clinical trials, 59.5% for frontal lessons, 55.5% for journal clubs, and 45.7% for clinical case discussions. Finally, more than half of the residents considered both seminars on leadership and on non-technical skills (58.9% and 56.5%, respectively) as useful contents for smart learning (Fig. 2B).

Overview of the Survey results. (A) Pie-charts showing the proportion of urology residents considering highly useful modalities of smart learning: pre-recorded videos (in yellow), interactive webinars (in green), podcasts (in red) and social media (in blue). (B) Pie-charts showing the proportion of urology residents considering highly useful contents for smart learning (in order from top to bottom, from left to right): surgical videos, clinical case discussions, frontal lessons, updates on guidelines, updates on clinical trials, journal clubs, seminars on leadership, seminars on non-technical skills.

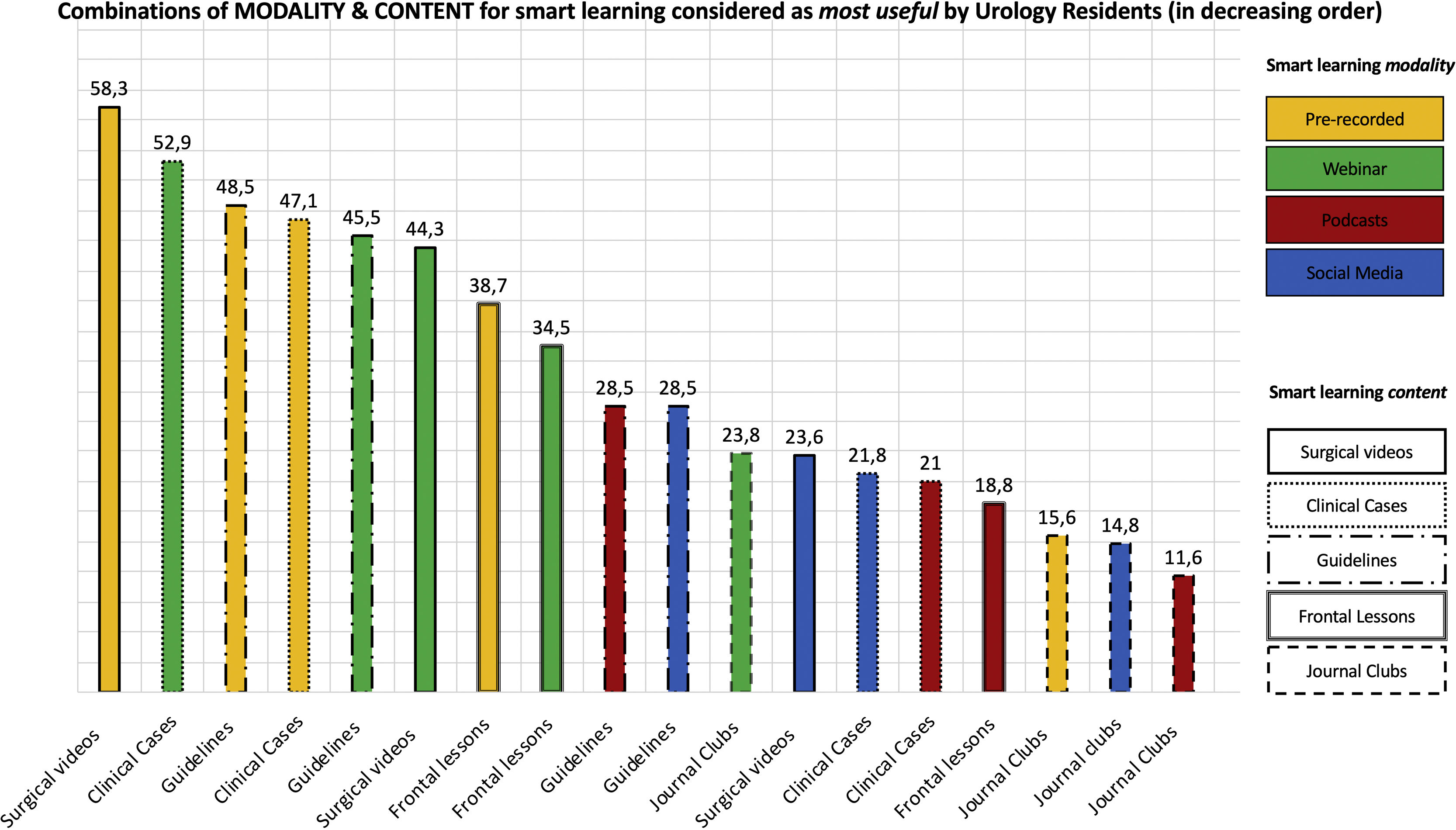

Fig. 3 shows the combinations of smart learning modality and contents considered as most useful by the urology residents completing the survey. The three preferred combinations were: (1) pre-recorded surgical videos (58.3%); (2) interactive webinars focused on clinical case discussions (52.9%); (3) pre-recorded videos providing updates on guidelines (48.5%). Journal clubs were the least preferred contents, regardless of the delivery modality (the only exception being via interactive webinars [23.8%]).

Combinations of modality and content for smart learning considered as most useful by urology residents (in decreasing order). Smart learning modalities are depicted using the yellow, green, red and blue colors for pre-recorded videos, webinars, podcasts and social media, respectively. This figure represents the graphical representation of the survey question no. 30 (“Which of the following combinations do you consider MOST USEFUL for smart learning Urology during the COVID-19 era?”). For this question, multiple answers were allowed for each participant (Appendix A).

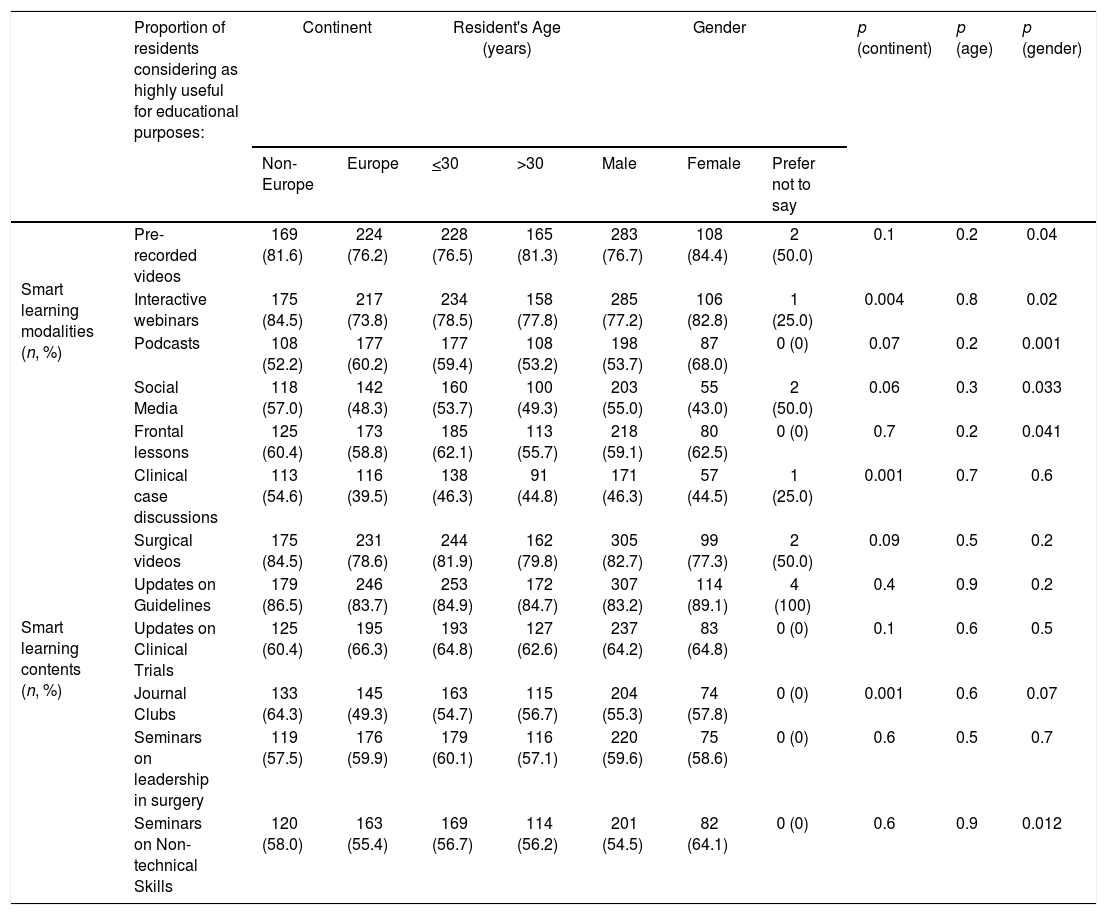

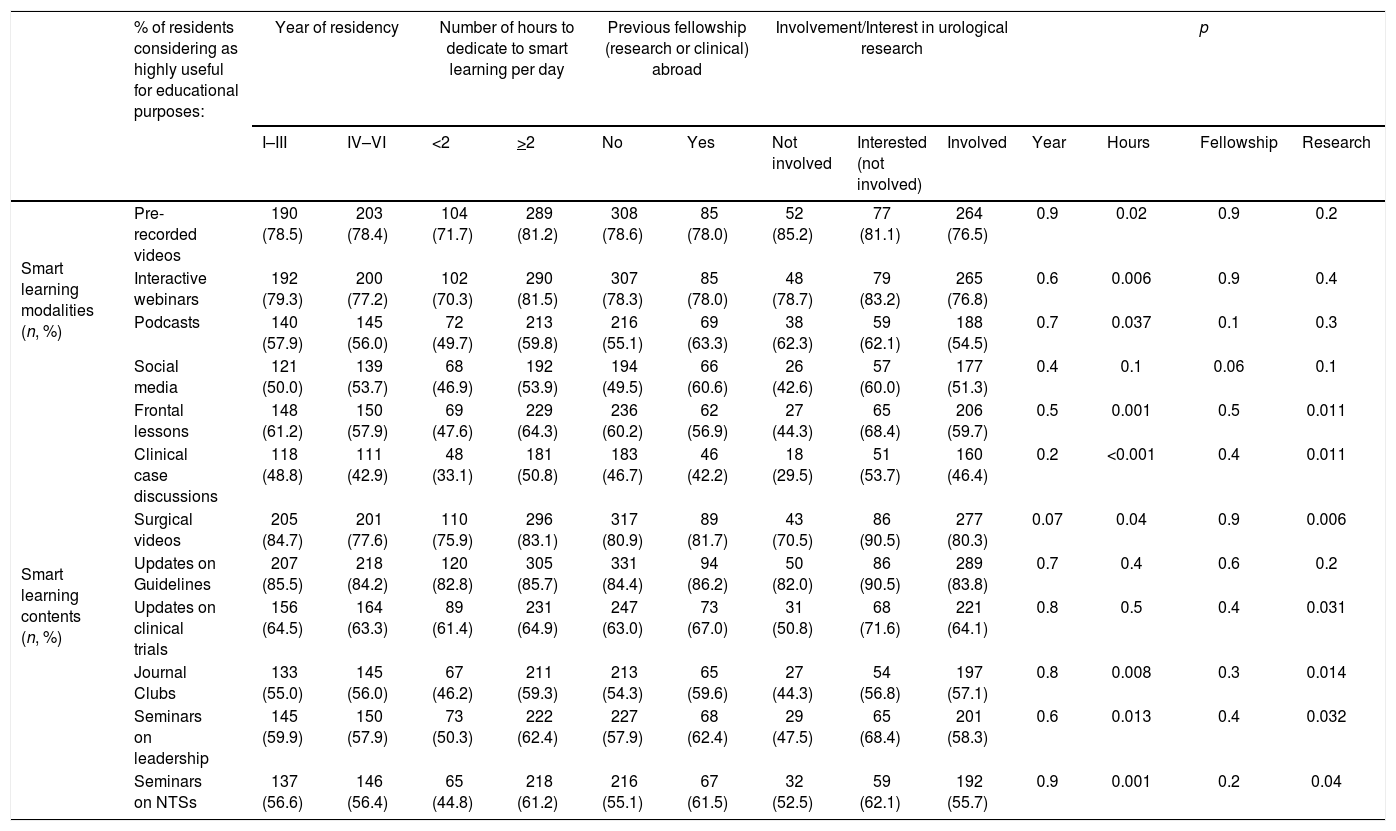

Tables 2 and 3 show the influence of baseline responders’ characteristics on the primary outcomes of the study. Age, year of residency, and previous fellowship experience did not significantly impact on the preference of residents regarding both smart learning modalities and contents, while the degree of interest/involvement in urological research influenced exclusively the opinion about the contents, except for the updates on guidelines (deemed as highly useful by the vast majority of responders). The only factor that was significantly associated with most preferences regarding both modalities and contents was the availability of at least 2h/day to dedicate to smart learning activities.

Influence of demographic characteristics of participants on the proportion of residents considering each modality and content for smart learning as highly useful.

| Proportion of residents considering as highly useful for educational purposes: | Continent | Resident's Age (years) | Gender | p (continent) | p (age) | p (gender) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Europe | Europe | <30 | >30 | Male | Female | Prefer not to say | |||||

| Smart learning modalities (n, %) | Pre-recorded videos | 169 (81.6) | 224 (76.2) | 228 (76.5) | 165 (81.3) | 283 (76.7) | 108 (84.4) | 2 (50.0) | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.04 |

| Interactive webinars | 175 (84.5) | 217 (73.8) | 234 (78.5) | 158 (77.8) | 285 (77.2) | 106 (82.8) | 1 (25.0) | 0.004 | 0.8 | 0.02 | |

| Podcasts | 108 (52.2) | 177 (60.2) | 177 (59.4) | 108 (53.2) | 198 (53.7) | 87 (68.0) | 0 (0) | 0.07 | 0.2 | 0.001 | |

| Social Media | 118 (57.0) | 142 (48.3) | 160 (53.7) | 100 (49.3) | 203 (55.0) | 55 (43.0) | 2 (50.0) | 0.06 | 0.3 | 0.033 | |

| Smart learning contents (n, %) | Frontal lessons | 125 (60.4) | 173 (58.8) | 185 (62.1) | 113 (55.7) | 218 (59.1) | 80 (62.5) | 0 (0) | 0.7 | 0.2 | 0.041 |

| Clinical case discussions | 113 (54.6) | 116 (39.5) | 138 (46.3) | 91 (44.8) | 171 (46.3) | 57 (44.5) | 1 (25.0) | 0.001 | 0.7 | 0.6 | |

| Surgical videos | 175 (84.5) | 231 (78.6) | 244 (81.9) | 162 (79.8) | 305 (82.7) | 99 (77.3) | 2 (50.0) | 0.09 | 0.5 | 0.2 | |

| Updates on Guidelines | 179 (86.5) | 246 (83.7) | 253 (84.9) | 172 (84.7) | 307 (83.2) | 114 (89.1) | 4 (100) | 0.4 | 0.9 | 0.2 | |

| Updates on Clinical Trials | 125 (60.4) | 195 (66.3) | 193 (64.8) | 127 (62.6) | 237 (64.2) | 83 (64.8) | 0 (0) | 0.1 | 0.6 | 0.5 | |

| Journal Clubs | 133 (64.3) | 145 (49.3) | 163 (54.7) | 115 (56.7) | 204 (55.3) | 74 (57.8) | 0 (0) | 0.001 | 0.6 | 0.07 | |

| Seminars on leadership in surgery | 119 (57.5) | 176 (59.9) | 179 (60.1) | 116 (57.1) | 220 (59.6) | 75 (58.6) | 0 (0) | 0.6 | 0.5 | 0.7 | |

| Seminars on Non-technical Skills | 120 (58.0) | 163 (55.4) | 169 (56.7) | 114 (56.2) | 201 (54.5) | 82 (64.1) | 0 (0) | 0.6 | 0.9 | 0.012 | |

Influence of training-specific characteristics of participants on the proportion of residents considering each modality and content for smart learning as highly useful.

| % of residents considering as highly useful for educational purposes: | Year of residency | Number of hours to dedicate to smart learning per day | Previous fellowship (research or clinical) abroad | Involvement/Interest in urological research | p | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I–III | IV–VI | <2 | >2 | No | Yes | Not involved | Interested (not involved) | Involved | Year | Hours | Fellowship | Research | ||

| Smart learning modalities (n, %) | Pre-recorded videos | 190 (78.5) | 203 (78.4) | 104 (71.7) | 289 (81.2) | 308 (78.6) | 85 (78.0) | 52 (85.2) | 77 (81.1) | 264 (76.5) | 0.9 | 0.02 | 0.9 | 0.2 |

| Interactive webinars | 192 (79.3) | 200 (77.2) | 102 (70.3) | 290 (81.5) | 307 (78.3) | 85 (78.0) | 48 (78.7) | 79 (83.2) | 265 (76.8) | 0.6 | 0.006 | 0.9 | 0.4 | |

| Podcasts | 140 (57.9) | 145 (56.0) | 72 (49.7) | 213 (59.8) | 216 (55.1) | 69 (63.3) | 38 (62.3) | 59 (62.1) | 188 (54.5) | 0.7 | 0.037 | 0.1 | 0.3 | |

| Social media | 121 (50.0) | 139 (53.7) | 68 (46.9) | 192 (53.9) | 194 (49.5) | 66 (60.6) | 26 (42.6) | 57 (60.0) | 177 (51.3) | 0.4 | 0.1 | 0.06 | 0.1 | |

| Smart learning contents (n, %) | Frontal lessons | 148 (61.2) | 150 (57.9) | 69 (47.6) | 229 (64.3) | 236 (60.2) | 62 (56.9) | 27 (44.3) | 65 (68.4) | 206 (59.7) | 0.5 | 0.001 | 0.5 | 0.011 |

| Clinical case discussions | 118 (48.8) | 111 (42.9) | 48 (33.1) | 181 (50.8) | 183 (46.7) | 46 (42.2) | 18 (29.5) | 51 (53.7) | 160 (46.4) | 0.2 | <0.001 | 0.4 | 0.011 | |

| Surgical videos | 205 (84.7) | 201 (77.6) | 110 (75.9) | 296 (83.1) | 317 (80.9) | 89 (81.7) | 43 (70.5) | 86 (90.5) | 277 (80.3) | 0.07 | 0.04 | 0.9 | 0.006 | |

| Updates on Guidelines | 207 (85.5) | 218 (84.2) | 120 (82.8) | 305 (85.7) | 331 (84.4) | 94 (86.2) | 50 (82.0) | 86 (90.5) | 289 (83.8) | 0.7 | 0.4 | 0.6 | 0.2 | |

| Updates on clinical trials | 156 (64.5) | 164 (63.3) | 89 (61.4) | 231 (64.9) | 247 (63.0) | 73 (67.0) | 31 (50.8) | 68 (71.6) | 221 (64.1) | 0.8 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.031 | |

| Journal Clubs | 133 (55.0) | 145 (56.0) | 67 (46.2) | 211 (59.3) | 213 (54.3) | 65 (59.6) | 27 (44.3) | 54 (56.8) | 197 (57.1) | 0.8 | 0.008 | 0.3 | 0.014 | |

| Seminars on leadership | 145 (59.9) | 150 (57.9) | 73 (50.3) | 222 (62.4) | 227 (57.9) | 68 (62.4) | 29 (47.5) | 65 (68.4) | 201 (58.3) | 0.6 | 0.013 | 0.4 | 0.032 | |

| Seminars on NTSs | 137 (56.6) | 146 (56.4) | 65 (44.8) | 218 (61.2) | 216 (55.1) | 67 (61.5) | 32 (52.5) | 59 (62.1) | 192 (55.7) | 0.9 | 0.001 | 0.2 | 0.04 | |

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first global web-based survey exploring residents’ perspective on smart learning modalities and contents for educational purposes. Of note, the survey was conducted during the COVID-19 outbreak; however, given the explosion in new technologies our findings have important implications beyond the pandemic in both the way to teach urology and the framework of virtual scientific meetings.13,14

Focusing on smart learning modalities, in line with a recent nationwide survey,11 both pre-recorded videos and interactive webinars warrant implementation within virtual learning programs. Despite lacking interaction, pre-recorded videos were preferred over interactive webinars, perhaps because it can offer the ability of trainees to independently manage their time and learning contents. Furthermore, our data highlight that podcasts and SoMe represent emerging options to broaden educational opportunities for trainees; SoMe may even allow to readily share pre-recorded videos and webinars with a broader audience.

Focusing on the smart learning contents, in our study cohort (mainly represented by residents involved in urological research) the most preferred were updates on guidelines, surgical videos and, to a lesser extent, adjournments on clinical trials, confirming previous findings.11 This highlights a compelling need for knowledge across the whole spectrum of learning fields, from the technical aspects of surgery to the latest news in research, with the “everlasting” role of guidelines as the backbone of evidence-based practice. Finally, more than 50% of residents demonstrated interest for two complimentary sets of skills (leadership and non-technical skills), underlying the will to expand their training beyond conventional learning contents.

Our findings should be interpreted in light of the study limitations. First, being disseminated primarily via Twitter and the COViD lecture series, our survey was not able to catch all the eligible residents worldwide. Correspondingly, our study population includes the residents who are likely to be more interested (and potentially more engaged) in smart learning activities, which may limit generalizability. Another limitation is the lack of data on downstream outcomes, such as knowledge of urology guidelines and technical skills. Finally, in light of its design as well as the channels used for its dissemination, it was not possible to formally calculate the survey's response rate.

Acknowledging these limitations, our findings provide a global “big picture” of the smart learning modalities and contents that could be prioritized in light of the residents’ perspective as a first step to optimize virtual Urology education during the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond.

ConclusionOur study offers a global overview of the residents’ perspective on smart learning modalities and contents for virtual urology education during the COVID-19 pandemic, providing a foundation to tailor future learning programs according to trainees’ needs and preferences.

Future studies are warranted to examine the long-term contribution of smart learning to urology resident training.

FundingStacy Loeb is supported by the Edward Blank and Sharon Cosloy-Blank Family Foundation.

Conflicts of interestStacy Loeb reports reimbursed travel from Sanofi and equity in Gilead.

The other Authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Joao Lemos Almeida (European Society of Residents in Urology (ESRU), Arnhem, The Netherlands, Department of Urology, Santa Maria University Hospital, Lisbon Medical Academic Center, Lisbon, Portugal). Cristian Fiori (Division of Urology, Department of Oncology, School of Medicine, San Luigi Hospital, University of Turin, Orbassano, Turin, Italy). Lindsay A. Hampson (Department of Urology, University of California San Francisco School of Medicine, San Francisco, CA, USA). Guglielmo Mantica (European Society of Residents in Urology (ESRU), Arnhem, The Netherlands, Department of Urology-Policlinico San Martino Hospital, University of Genova, Genova, Italy). Andrea Minervini (Department of Urology, Careggi Hospital, University of Florence, Florence, Italy, Department of Experimental and Clinical Medicine, University of Florence, Florence, Italy). Alberto Olivero (Department of Urology-Policlinico San Martino Hospital, University of Genova, Genova, Italy). Luis Enrique Ortega Polledo(European Society of Residents in Urology (ESRU), Arnhem, The Netherlands, Principe de Asturias University Hospital, Department of Urology, Madrid, Spain). Karl H. Pang (European Society of Residents in Urology (ESRU), Arnhem, The Netherlands, Department of Oncology and Metabolism and Academic Urology Unit, University of Sheffield, United Kingdom). Rocco Papalia (Department of Urology, Campus Biomedico, University of Rome, Rome, Italy). Benjamin Pradere (Department of Urology, CHRU Tours, Francois Rabelais University, Tours, France, Department of Urology, Comprehensive Cancer Center, Medical University of Vienna, Vienna, Austria). Fatih Sandikci (European Society of Residents in Urology (ESRU), Arnhem, The Netherlands, Department of Urology, University of Health Sciences, Dışkapı Yıldırım Beyazıt Training and Research Hospital, Ankara, Turkey). Jose Daniel Subiela (Oncology Urology Unit, Department of Urology, Fundació Puigvert, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain). Maxime Vallée (European Society of Residents in Urology (ESRU), Arnhem, The Netherlands, Department of Urology, Poitiers University Hospital, Poitiers, France). Junlong Zhuang (Department of Urology, Drum Tower Hospital, Medical School of Nanjing University, Institute of Urology, Nanjing University, Nanjing, Jiangsu, China).

Please cite this article as: Campi R, Amparore D, Checcucci E, Claps F, Teoh JY-C, Serni S, et al. Explorando la perspectiva de los residentes sobre las modalidades y contenidos de aprendizaje inteligente para la educación virtual de urología: lección aprendida durante la pandemia de la COVID-19. Actas Urol Esp. 2021;45:39–48.