Following the outbreak of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, normal surgical activity has been relegated to the new hospital reorganization required to ensure continuity of care, except for those surgical emergencies and oncological surgical procedures whose delay would result in unacceptable risk to the patient. In the present phase, it is necessary to resume the activity that was delayed together with all surgical procedures, oncological or not, that are indicated in the consultation activity.

The objective of this article is to collect the recommendations with the greatest scientific evidence to guarantee patient safety in these procedures, as well as tools that help in the selection of patients taking into account resource optimization criteria, focusing on an area of urology that deals with non-oncological pathology: functional urology.

MethodsA review of the existing literature and the recommendations of the Spanish Association of Surgeons (AEC, for its acronym in Spanish), American College of Surgeons (ACS), American Urological Association (AUA), Royal College of Surgeons (RCS), European Association of Urology (EAU), Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), National Health System (NHS) and the World Health Organization (WHO) has been conducted from March 14, 2020, the date of the declaration of the state of alarm in Spain, to the present. Information regarding the criteria for delaying surgical urological procedures that necessarily occurred during the peak of the pandemic, the existing protocols and current recommendations regarding the perioperative period, from preoperative to discharge, and possible tools that may be helpful in the selection of the most appropriate patients when it comes to resuming surgical activity in functional urological surgery today.

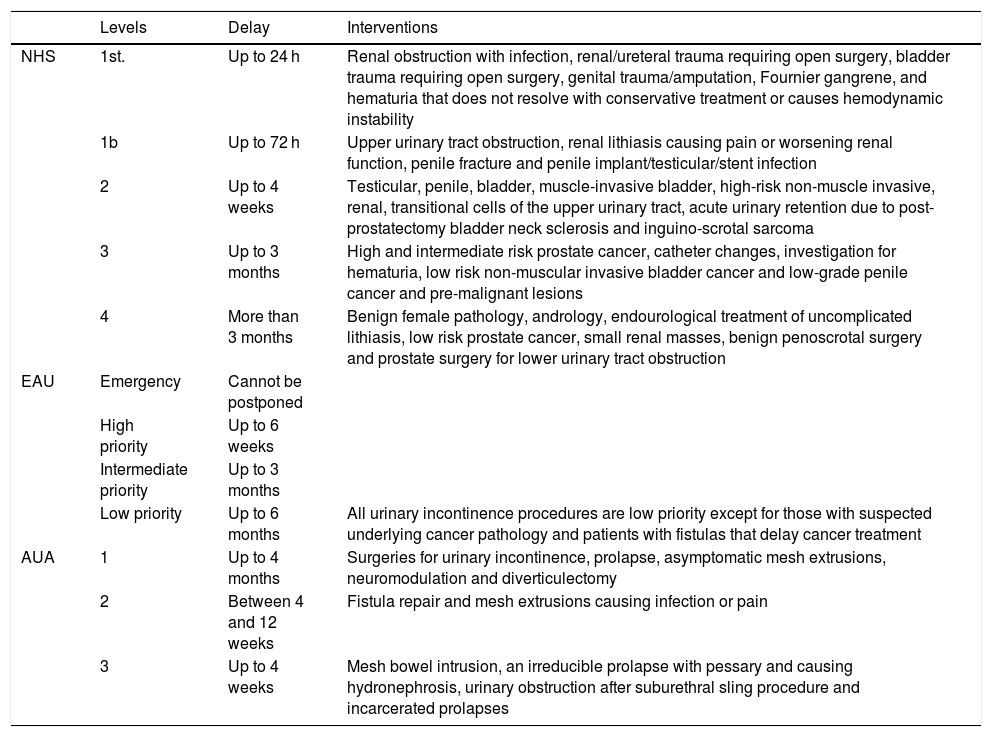

ResultsThe British NHS was the first to publish guides on general surgical prioritization criteria on 11 April 2020.1 The EAU published their recommendations on 14 April 2020. These guides are not only related to surgery, but they include diagnosis and follow-up as well, in a more detailed way.2

On April 28, 2020, a consensus document was published by all American Urogynecological associations and collected by the AUA, which in addition classified these pathologies by levels3 (Table 1).

Recommendations of the NHS, EAU and AUA for urological and urogynecological procedures in the context of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic.

| Levels | Delay | Interventions | |

|---|---|---|---|

| NHS | 1st. | Up to 24 h | Renal obstruction with infection, renal/ureteral trauma requiring open surgery, bladder trauma requiring open surgery, genital trauma/amputation, Fournier gangrene, and hematuria that does not resolve with conservative treatment or causes hemodynamic instability |

| 1b | Up to 72 h | Upper urinary tract obstruction, renal lithiasis causing pain or worsening renal function, penile fracture and penile implant/testicular/stent infection | |

| 2 | Up to 4 weeks | Testicular, penile, bladder, muscle-invasive bladder, high-risk non-muscle invasive, renal, transitional cells of the upper urinary tract, acute urinary retention due to post-prostatectomy bladder neck sclerosis and inguino-scrotal sarcoma | |

| 3 | Up to 3 months | High and intermediate risk prostate cancer, catheter changes, investigation for hematuria, low risk non-muscular invasive bladder cancer and low-grade penile cancer and pre-malignant lesions | |

| 4 | More than 3 months | Benign female pathology, andrology, endourological treatment of uncomplicated lithiasis, low risk prostate cancer, small renal masses, benign penoscrotal surgery and prostate surgery for lower urinary tract obstruction | |

| EAU | Emergency | Cannot be postponed | |

| High priority | Up to 6 weeks | ||

| Intermediate priority | Up to 3 months | ||

| Low priority | Up to 6 months | All urinary incontinence procedures are low priority except for those with suspected underlying cancer pathology and patients with fistulas that delay cancer treatment | |

| AUA | 1 | Up to 4 months | Surgeries for urinary incontinence, prolapse, asymptomatic mesh extrusions, neuromodulation and diverticulectomy |

| 2 | Between 4 and 12 weeks | Fistula repair and mesh extrusions causing infection or pain | |

| 3 | Up to 4 weeks | Mesh bowel intrusion, an irreducible prolapse with pessary and causing hydronephrosis, urinary obstruction after suburethral sling procedure and incarcerated prolapses |

In this scenario, patient safety and safe surgery, aspects on which the WHO has been working for years, gain special importance.4

The AUA and the RCS have published recommendations for the resumption of surgical care.5,6 They highlight the importance of knowing the community’s prevalence and incidence, the capability to perform CRP on both patients and health care workers, the availability of protective equipment, the facility capacity such as ICU beds or ventilators, the prioritization of procedures according to resources and ensuring safe, high-quality care.

In this line, the CDC recommends being prepared to rapidly detect an increase of COVID-19 cases in the community, providing care in the safest way possible by minimizing in-person appointments and gradually expanding to provide elective services.7

The AEC has outlined 5 phases organized according to objective criteria such as the percentage of hospitalization/ICU beds occupied by patients with SARS-CoV-2, the need for emergency triage in patients with respiratory symptoms, the impact on resources and the impact on surgical activity. Depending on the stage we are at, certain types of procedures would be justified.8

DiscussionThe SARS-CoV-2 pandemic has challenged the identity of medical professionals because, as experts in our corresponding fields, we are used to knowing the answers, have some predictive ability, rely on routines, and have a sense of competence in what we do.

This situation has had an unexpected beginning that has forced us to slow down, producing feelings of fear (for patients and for the personnel involved in their care) to which we must respond with courage and acknowledging our vulnerabilities. It creates uncertainty, to which we must respond from the scientific method, and a sense of loss of control, to which we must act from medical knowledge.

The pandemic has led to under-utilization of medical services in patients with urgent and emerging problems, creating a situation that creates a "second wave" of patients needing health care for problems not related to SARS-CoV-2.9–11

In the most acute phase of the pandemic, it has been essential to reorganize all hospital resources, both human and material, to provide healthcare services for patients with SARS-CoV-2, focusing all responses on knowing how long the various surgical procedures could be delayed–3.

However, at the present time, the infection rate has dropped significantly, as we can see in the last update of the Ministry of Health and Consumer Affairs consulted for this publication. In this update, the Community of Madrid has registered 59 cases requiring hospitalization and 7 cases requiring ICU admission, with an increase in confirmed cases of 0.1%.12

In this scenario, it is no longer sufficient to continue delaying procedures if the hospital situation allows it, based on objective criteria such as those established by the AEC.8 Although obviously the risks assumed with a patient undergoing surgery during the incubation period are high,13 there are already delayed pathologies, and others that cause quality of life deterioration which makes the patient want to undergo surgery, especially when we do not know how long the pandemic will last, or if there will be a second wave in the fall requiring a new redistribution of resources with the necessary delay of non-urgent procedures.

There is little information regarding selection criteria for surgical indication, except for the previously mentioned delaying criteria, and we found interesting the classification proposed by Prachand et al.14 adopted by the ACS. Since the term "elective surgery" may seem to refer to "optional" surgery, they propose the MeNTS scale: Medically Necessary, Time-Sensitive. It refers to a case prioritization process based on medical necessity and time sensitivity. It is a scale based on 21 factors structured in 3 domains: underlying disease, respiratory pathology/SARS-CoV-2 and surgical procedure, in which a score ranging from 21 to 105 points is obtained, not being recommended to intervene a patient above a score of 57, because of its association with poorer outcomes, increased risk for healthcare team and excessive hospital resource use.

We find the review of this methodology interesting for functional urology, since it is not only limited to delay, but it takes into account non-oncological pathologies and can serve as an additional objective criterion in this phase of the pandemic in which we are at.

Regardless of the selection criteria, it is essential, in order to resume surgical activity, to follow all the safe surgery recommendations of the WHO4 together with those of the different medical societies, such as the ACS, which emphasize "ensuring safe, high-quality, high-value care of the surgical patient across the Five Phases of Care continuum."5 These phases are:

- -

Preoperative period:

- •

consider repeating ancillary tests

- •

identify new comorbidities

- •

screen for symptoms or contact with SARS-CoV-2 infection patients

- •

perform PCR testing.

- -

Immediate Preoperative Period:

- •

review surgery, anesthesia and nursing checklists for potential need to be revised and adapted to the new situation.

- -

Intraoperative Period:

- •

follow the recommendations regarding intubation

- •

waiting times

- •

use of protective equipment

- •

specimen pick-up protocol.

- -

Postoperative period:

- •

adhere to established protocols to optimize hospital stay and efficiency, decreasing complication rates.

- -

Discharge Period:

- •

provide home care to minimize situations that require re-entry.

The main limitations we find are the lack of information regarding functional urology, the precariousness of publications at this stage and the uncertainty generated in the near future by possible outbreaks of the pandemic.

In conclusion, once the continuity of health care services is guaranteed at the time of the pandemic, it is required, with strict scientific criteria and according to the various medical societies, to make the adaptation to the new reality, maximizing the safety of patients and personnel. In this regard, as the number of SARS-CoV-2 positive patients continues to decline, delayed procedures will be less justified. Likewise, tools are needed to help in the correct selection of "operable" patients such as those in functional urology, which although they present benign pathologies, affect the patients' quality of life.

Please cite this article as: Garde-García H, González-López R, González-Enguita C. Cirugía urológica funcional y SARS-CoV-2: cómo y por qué hay que retomar ya la actividad quirúrgica adaptados a la nueva realidad. Actas Urol Esp. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acuro.2020.06.001