Fifteen-year-old female patient, previously healthy, referred to our center for presenting abdominal pain, vomiting, diarrhea, malar erythema, palpebral and lower limb edema, arthralgia, morning stiffness and bilateral blurred vision. Laboratory and imaging studies together with the clinic allowed the diagnosis of nephrotic syndrome secondary to systemic lupus erythematosus. Ophthalmology examination revealed a visual acuity of 8/10 in both eyes and bilateral disc edema with partial macular star, findings compatible with bilateral neuroretinitis. Renal biopsy established the diagnosis of membranous lupus nephritis. Immunosuppressive treatment was started, obtaining gradual clinical improvement.

Although systemic lupus erythematosus with membranous lupus nephritis and neuroretinitis is a very infrequent association, when faced with a patient with bilateral neuroretinitis, we must consider systemic lupus erythematosus within the differential diagnoses.

Joven de 15 años, previamente sana, se presentó con dolor abdominal, vómitos, diarrea, eritema malar, edema palpebral y en miembros inferiores, artralgias, rigidez matinal y visión borrosa bilateral. Estudios de laboratorio y por imágenes junto con la clínica permitieron realizar el diagnóstico de síndrome nefrótico secundario a lupus eritematoso sistémico. Al examen oftalmológico se constató 8/10 de visión en ambos ojos y edema de papila bilateral con estrella macular parcial, hallazgos compatibles con una neurorretinitis bilateral. La biopsia renal estableció el diagnóstico de nefritis lúpica membranosa. Se inició tratamiento inmunosupresor, con mejoría clínica gradual.

Si bien el lupus eritematoso sistémico con nefritis lúpica membranosa y neurorretinitis es una asociación muy infrecuente, frente a un paciente con neurorretinitis bilateral debemos considerar al lupus eritematoso sistémico dentro de los diagnósticos diferenciales.

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a chronic multisystem autoimmune disease with a broad range of clinical expressions, predominantly affecting women of childbearing age. The prevalence in children is one per 100,0001. Various genetic, hormonal, environmental and immunological factors are involved in its pathogenesis1.

Renal involvement occurs in 40%–80% of SLE patients, with involvement ranging from microhematuria/proteinuria to renal failure. About 90% of SLE patients have some type of kidney injury, with diffuse proliferative lupus nephritis (LN) (class iii-iv) being the most common. Membranous LN (class v) with massive proteinuria is a rare form2,3.

SLE can affect any part of the eye and its adnexa, through inflammatory or thrombotic processes. Ocular manifestations have been reported in approximately one third of SLE patients, the most frequent being keratoconjunctivitis sicca, followed by scleritis, episcleritis, lupus retinopathy and lupus choroidopathy. Neuroretinitis (NR) is very rare, with very few cases reported in the literature. Ocular involvement may correlate with disease activity and precede other systemic symptoms4.

A case of bilateral NR in a 15-year-old female patient with newly diagnosed SLE and membranous NL is presented.

Clinical caseFemale, 15, previously healthy, referred to our hospital for abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea and weight loss of 4 months’ duration, followed by butterfly wing erythema, erythematous lesions on the arms, eyelid and lower limb eedema, arthralgia, morning stiffness and bilateral blurred vision. No history of fever or headache. On examination she was always normotensive. Suspecting nephrotic syndrome secondary to SLE, blood and urine tests were requested, finding normal hemogram and renal function, hypercholesterolaemia, hypertriglyceridemia, hypoalbuminemia, hypocomplementemia (C3: 31 mg/dl; C4: 10 mg/dl), increased ESR (greater than 120 mm/h), positive ANA (titre 1/1.280), positive anti-DNA antibody (titre 1/160), positive anti-Sm antibody, normal antiphospholipid antibodies, massive proteinuria and microhaematuria. Abdominal ultrasound showed free fluid in the abdomen and bilateral laminar pleural effusion. Echocardiogram was normal. Given these findings, the diagnosis of SLE was confirmed according to the ACR and EULAR criteria of 20195.

Ultrasound-guided renal biopsy was indicated, which established the diagnosis of membranous LN, class v according to the ISN/RPS classification6.

Treatment was started with meprednisone 60 mg/day (Deltisone B, Elea Phoenix, S. A., Los Polvorines, Buenos Aires, Argentina), hydroxychloroquine 400 mg/day (Evoquin, Ivax Argentina, S. A., Villa Adelina, Buenos Aires, Argentina), mycophenolate mofetil 2 g/day (CellCept, Productos Roche, S. A. Química e Industrial, Argentina), enalapril (Lotrial, Roemmers, Olivos, Buenos Aires, Argentina), losartan (Losacor, Roemmers, Olivos, Buenos Aires, Argentina), calcium carbonate (Calcio Base Efervescente, Investi Farma, S. A., Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires, Argentina) and vitamin D (Raquiferol D3, Roemmers, Olivos, Buenos Aires, Argentina).

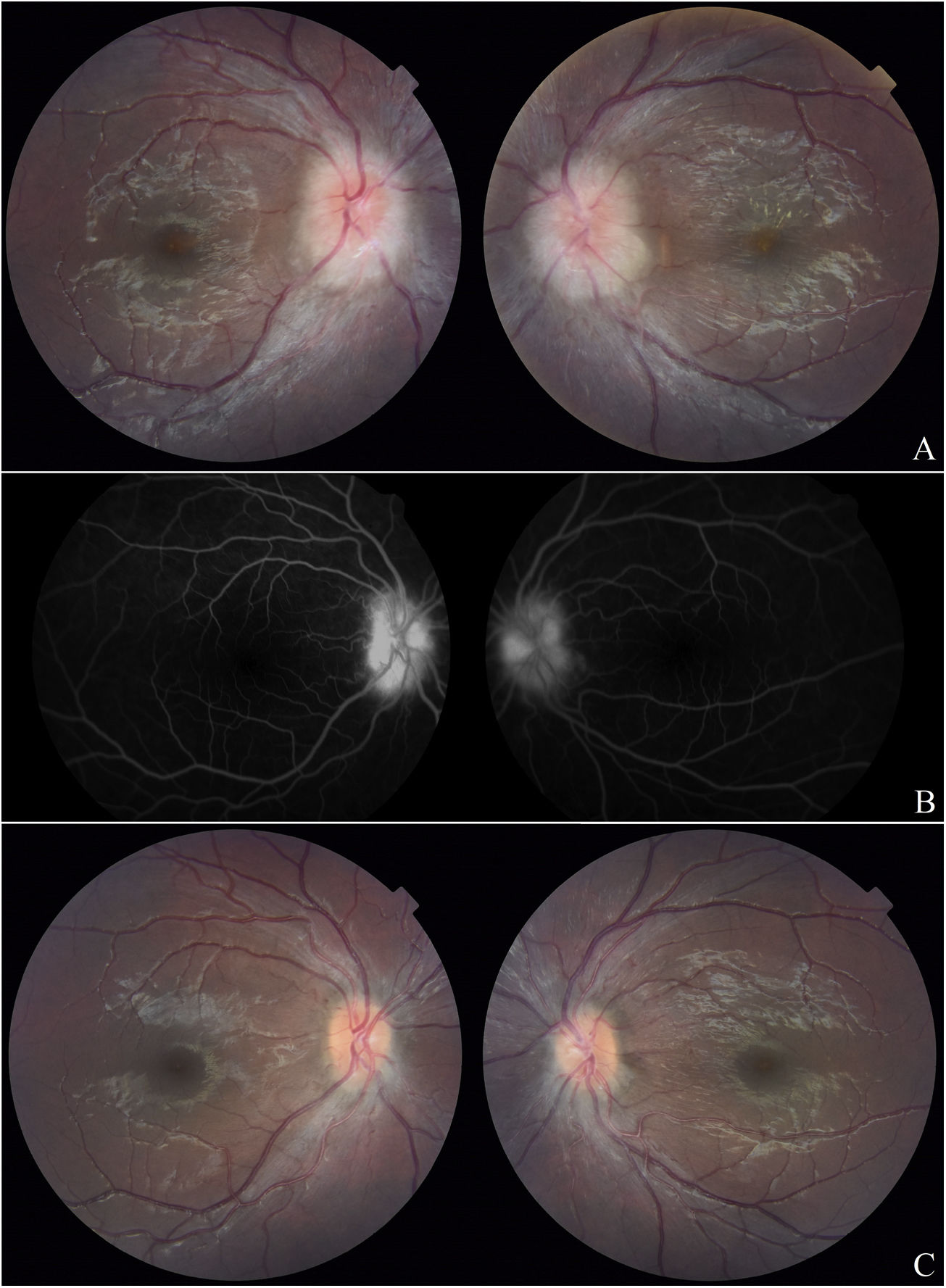

Ophthalmological evaluation was requested, which revealed best corrected visual acuity of 8/10 in BE, isochoric pupils, preserved photomotor and consensual reflexes, preserved extrinsic ocular motility, normal intraocular pressure, absence of cells in the anterior chamber and vitreous cavity, and bilateral papilla edema with partial macular star more evident in the left eye, findings compatible with bilateral NR (Fig. 1A).

A. Fundus photograph one month after the start of immunosuppression: bilateral papillary edema with partial macular star in the left eye and scant macular exudates in the right eye. B. Fluorescein angiography: papillary hyperfluorescence with leakage in the arteriovenous time in BE. C. Fundus photograph 7 months after the start of immunosuppression: clear papilla with no macular exudates.

Studies were ordered and performed 3 months later. Fluorescein angiography showed papillary hyperfluorescence with early arteriovenous time leakage increasing at later angiogram times in BE (Fig. 1B). Macular optical coherence tomography, computerised visual field and brain MRI were normal.

Systemic treatment was continued and complete remission of extrarenal symptoms was achieved 3 months after start of treatment.

Four months after starting treatment, the patient developed severe cellulitis on her right thigh, which required admission and intravenous antibiotic treatment. This infection exacerbated the proteinuria and led to a temporary decrease in immunosuppression. Once the infectious process was overcome, immunosuppressants were resumed at previous doses.

Within 6 months of starting immunosuppression, the nephrotic syndrome subsided and proteinuria gradually improved and disappeared by 1 year.

In what concerns the ophthalmological picture, macular exudates disappeared 2 months after the start of immunosuppression, visual acuity reached 10/10 in BE at 3 months and papillary edema slowly decreased until it disappeared completely at 7 months (Fig. 1C).

DiscussionSLE is a rare disease in paediatrics; it should always be suspected in the presence of nephrotic syndrome in adolescents, especially female, as secondary causes are more frequent at this age.

NL occurs in about 50%–82% of children with SLE, and within this, the membranous class accounts for 8%–20% of cases in adults, with an unknown frequency in paediatrics. In membranous NL, half of the patients with hematuria also have proteinuria and often develop nephrotic syndrome, as seen in this case. The response to treatment is usually later than in proliferative forms; however, it has a better prognosis, with a renal survival of 85% at 5 years3,7. Such a situation was observed in this patient, who required one year to achieve complete clinical improvement.

NR is an inflammatory disorder of the optic disc presenting with the triad of decreased vision, optic disc edema and characteristic macular star formation. The condition is usually unilateral, but can be bilateral in both immunocompetent and immunocompromised patients. When bilateral, ocular involvement is usually asymmetric. Pathophysiologically, there is swelling and exudation of the deep capillaries of the optic disc, with subsequent accumulation of fluid in the peripapillary retina and macula. Subsequently, the edema gradually resolves leaving lipoprotein deposits (hard exudates) within the outer plexiform layer, which appear star-shaped due to the radial arrangement of Henle’s fibres within this layer. The macular star may be partial or complete; when partial, it is usually present in the nasal macula8,9.

NR can be classified according to its etiology as infectious, non-infectious or inflammatory, and idiopathic (Table 1)8,10. Cat scratch disease, caused by infection with the bacterium Bartonella henselae, is the most common cause and accounts for two-thirds of cases. Fifty percent of cases have no identifiable cause and are idiopathic Leber’s NR10.

Causes of neuroretinitis.

| Infectious |

| Bacterial: cat-scratch disease, tuberculosis, syphilis, leptospirosis, salmonellosis, typhoid, Lyme disease, actinomycosis |

| Viral: chickenpox, herpes simplex, herpes zoster, Epstein-Barr, influenza A, hepatitis B, mumps, measles, rubella, zika, chikungunya, West Nile virus. |

| Parasitic: toxoplasmosis, toxocariasis, unilateral subacute diffuse neuroretinitis |

| Fungal: histoplasmosis, coccidioidomycosis |

| Inflammatory |

| Sarcoidosis |

| LES |

| Behçet’s disease |

| IRVAN syndrome |

| Polyarteritis nodosa |

| Takayasu’s arteritis |

| Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada Syndrome |

| Inflammatory bowel disease |

| Idiopathic |

| Leber’s idiopathic stellate neuroretinitis |

Typically, optic disc edema precedes the macular star by 1–3 weeks, and both resolve in approximately 8–12 weeks8–10. In our patient, the slow resolution of optic disc edema may be related to the delayed therapeutic response of her underlying disease, given the histological type of her renal disease, as well as the transient decrease in immunosuppression required by its infectious intercurrence.

The differential diagnosis of NR should include malignant hypertension, which can occur in these cases and produce bilateral papillary edema with lipid exudation similar to that described at8. This patient’s blood pressure was always within normal parameters, so this differential diagnosis was ruled out.

Most of the literature does not mention SLE as a cause of NR and vice versa, NR as an ophthalmological manifestation of SLE. Only a few case reports have been published, some of them associated with antiphospholipid syndrome, making SLE with membranous LN and NR a very rare association.

ConclusionUnlike the other microvascular networks, the retinal microvasculature can be directly examined by fundoscopy, and these findings may be comparable with the microangiopathic status in the brain as well as in the rest of the body. As fundoscopy is a simple and accessible test, it should be part of the initial evaluation in every patient with SLE. Perhaps the low prevalence of ophthalmological manifestations has been underestimated due to lack of screening.

In addition to funduscopic examination, other supplementary examinations such as OCT angiography, fluorescein angiography and indocyanine green angiography may reveal vascular changes in the superficial and deep retinal plexuses and in the choroid, which may not be clinically apparent in SLE-associated chorioretinal involvement. Said studies (OCT angiography, fluorescein angiography and indocyanine green angiography) can be performed with DRI OCT-1 Triton plus, 3D Optical Coherence Tomography, Topcon Corporation, Tokyo, Japan (Note: Indocyanine green angiography is not performed in Argentina).

In conclusion, when faced with a patient with bilateral NR, SLE should be considered among the differential diagnoses. It responds to immunosuppressive treatment for SLE and has an excellent long-term prognosis.

FundingThe authors did not receive funding to carry out their research.

Conflict of interestNo conflicts of interest were declared by the authors.