Migraine continues second among the world's causes of disability. Diagnosis is based on the history and clinical examination and imaging is usually not necessary. Migraine can be subdivided depending on whether there is an aura or not and based on the frequency of the headaches. The number of headache days determines whether the patient has episodic migraine or chronic migraine. Treating migraines can be done to treatment the migraine itself and to prevent its appearance. In this review we approach the migraine from a practical point of view with updated information.

La migraña continúa siendo la segunda causa a nivel mundial de discapacidad. El diagnóstico se basa en la historia clínica y el examen clínico y las imágenes no suelen ser necesarias. La migraña se puede subdividir dependiendo de si hay un aura o no y según la frecuencia de la cefalea. El número de días con cefalea determina si el paciente tiene migraña episódica o migraña crónica. El tratamiento de las migrañas se puede realizar para tratar la migraña en sí y para prevenir su aparición. En esta revisión abordamos la migraña desde un punto de vista práctico con las últimas novedades.

Migraine is the most frequent neurological problem in Primary Care. According to the findings of the last Global Burden Disease study, migraine continues second among the world's causes of disability, and first among young women.1 Migraine is a frequent disorder as it affects 18% of women and 6% of men, while chronic migraine affects 2% of the global population, and it is extremely burdening condition for the patients, their families and the society.2

Careful anamnesis and physical examination are the key for the diagnosis. Testing is usually not required. Treatment is based on nonpharmacological and pharmacological interventions. Pharmacological interventions are to treat the headache and to prevent it.

MethodsUpdated information on migraine headaches management is important of Family Physicians. Here, we review the available literature on migraine headaches. Relevant articles were identified by a literature search in PubMed. Further selection of articles was achieved by focusing on the following key points: diagnostic and definition criteria of migraine; features of migraine headaches; acute management of migraine; preventive treatment of migraine; new migraine treatments. In addition, the authors’ clinical experience of migraine have been utilized to propose a schema to assist in the assessment and treatment of migraines in a Primary Care setting.

Migraine definitionMigraine is a familial, episodic and complex sensory processing disturbance3 which associates a constellation of symptoms, being headache the hallmark.

The migraine attack can last 4–72h and it consists of 4 overlapping phases.4

a) Premonitory phase: Non-painful symptoms appearing hours or days before the onset of the headache. These symptoms can include yawning, mood changes, difficulty concentrating, neck stiffness, fatigue, thirst and elevated frequency of micturition.5

b) Aura: About one third of the patients with migraine, especially women, suffer this transient focal neurological symptom before or during some of their headaches which is called aura. Visual aura is the most common type (90%) followed by sensory (30–54%) and language aura (31%).6 Motor, brainstem and retinal aura are atypical and therefore far less often.

c) Headache: This phase is caused by the activation of the trigeminal sensory pathways which generates the throbbing pain of migraine.4 The intensity of the headache increases progressively or is explosive at the onset and disrupts daily activities. Headache typically gets worse with head movement. It is usually associated with nausea and vomiting with an aversion to touch (allodynia), light (photophobia), sound (phonophobia), and smell (osmophobia).

4) Postdrome: The most frequent symptoms in this phase are tiredness, drowsiness, difficulty in concentrating and hypersensitivity to noise.7 The greater the intensity of the pain, the more intense and prolonged these symptoms will be. This phase is colloquially known among patients as the “migraine hangover”.

Migraine can be subdivided depending on whether there is an aura or not and based on the frequency of the headaches.

Migraine with visual aura involves visual effects that usually preceded the headache and last at least 5min. The visual aura is typically an expanding blinding spot or visual scintillations (shimmering objects in the visual field). Blurred vision is not sufficient to diagnose aura. Other aura features include reversible symptoms of speech and language difficulty such as word finding problems and even aphasia (unable to express words or comprehend words), sensory phenomenon such as tingling in the extremities extending to the face, motor effects such as weakness and brainstem problems such as unsteadiness and features of cranial nerve dysfunction. These aura symptoms usually last 5–60min. They can precede or start during the headache and can also occur without a headache.

To diagnose migraine, the patient should have had at least 5 attacks that involve migraine features as outlined below. In adults: the untreated attacks usually last 4 or more hours. A migraine requires only two of the following four headache features: a unilateral distribution (one sided), pulsatile quality (throbbing), moderate or severe pain (more than 5 out of 10), and aggravation by physical activity (such as bending over). In addition to diagnose migraine only one of the following is required: nausea or vomiting; or sensitivity to light and noise.

The number of headache days determines whether the patient has episodic migraine (14 or fewer headache days a month) or chronic migraine (more than 15 days of headache a month). The best method of determining the actual number of headache days is to subtract this from the number of completely free headache days in a month, also called crystal clear days. If headache is present on more than half the days in the month, and there are migraine features on at least 8 days a month, the condition is termed chronic migraine.

If headache is present on less than 15 days a month this is referred to as episodic migraine.

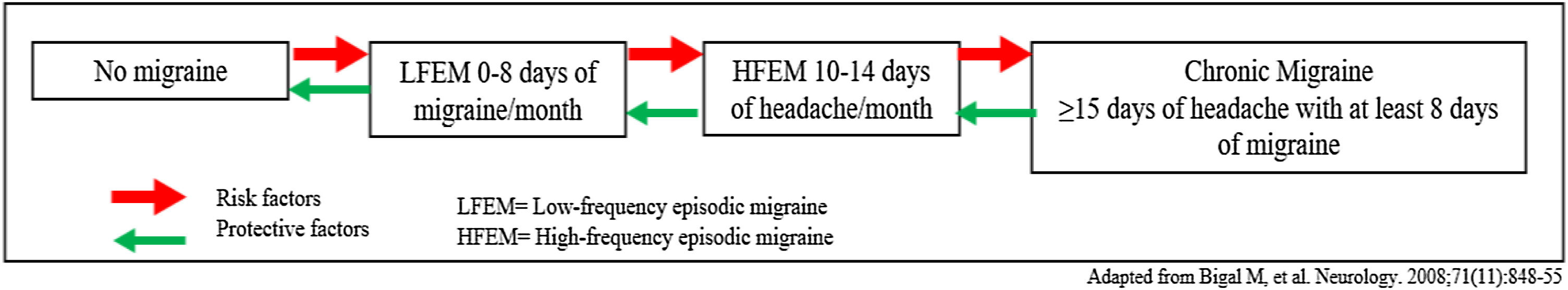

This “migraine chronification” (formerly called transformation) has been conceptualized in terms of a transitional model (Fig. 1) which is often used to talk about migraine as a dynamic disease that can progress in both directions.8 In this regard, it is important to identify risk factors and protective factors.

Patients with episodic migraine may become chronic in their pain and this fact can be explained as a threshold problem: A genetic predisposition in combination with ambient factors (stressful life events, obesity depression…), and frequent headache pain, lower the threshold of migraine attacks, thus enhancing the risk of chronic migraine.9

Neuroimaging in migraineThere is no necessity to do neuroimaging10 in patients with headaches consistent with migraine who have a normal neurologic examination, and there are no atypical features or alarm signs present.

Criteria for ordering an MRINeuroimaging may be performed for presumed migraine for the following reasons: unusual, prolonged, or persistent aura; increasing frequency, severity, or change in clinical features, first or worst migraine, migraine with brainstem aura, migraine with confusion, migraine with motor manifestations (hemiplegic migraine), late-life migraine accompaniments, aura without headache, side-locked headache, and posttraumatic headache.

TreatmentIt should be explained to the patient that migraine is a recurrent and episodic disease that currently has no cure and that in general allows an adequate quality of life when it is known and treated. Inadequate treatment of migraine attack has a huge socio-economic impact and also increases the risk of transformation of migraine into its chronic forms.11

Migraine treatment consist of non-pharmacologic and pharmacologic options.

Non-pharmacologicLifestyle modificationsLifestyle factors of sleep, meal habits, stress and physical exercise routine are known to be related to migraine evolution. An observational study of 350 migraine patients showed that chronic migraine individuals exhibit significantly less regular lifestyle behaviors of sleep, exercise and meal time that episodic migraine patients. Perceived stress scores are higher in chronic migraine patients compared to controls. The relationship between headache and sleep is bidirectional: suboptimal sleep habits can worsen migraine frequency and migraine can decrease the quality of sleep.

The five factors identified as the most common triggers of migraine are: stress, fasting, atmospheric changes, sleep-related factors, and in women hormonal fluctuations.12 Triggers should be addressed in the anamnesis and recommendation of lifestyle changes should be made for all patients.

Performing a headache calendar should be the first step in every patient with migraine, allowing the physician to monitor the interventions in a quantitative way (i.e., changes in the total number of headache days per month). Even though, the global status of the patient should be taken into consideration, as some patient may experience very few headache days and still be incapacitated.

Attending to the evidence provided in the referred studies, the 6 most important aspects in the migraine non-pharmacological treatment are:

- 1.

Set routines and fixed schedules are recommended. A regular and sufficient period of rest at night is recommended, as sleep improvement alone can revert a chronic migraine into the episodic form.

- 2.

Abundant hydration, since dehydration is a frequent cause of migraine attacks.

- 3.

Aerobic exercise: There is much evidence in favor of the preventive role of moderate exercise performed regularly. A trial of 91 migraine patients randomized to an exercise routine (40min 3 times a week), a relaxation program, to topiramate at the highest tolerable dose for a period of 3 months showed a similar benefit of topiramate and physical exercise with no statistical differences.

Avoiding stressful situations.

- 4.

Avoiding fasting.

- 5.

Relaxation therapies, mindfulness and especially yoga. Recently, a clinical trial has proven the benefits of yoga as an add-on therapy for migraine patients, achieving a greater pain control, lesser disability scores and lesser acute medication intake than medical therapy alone.

Other important aspects are:

- •

Excess or abstinence in regular caffeine drinkers can make migraines worse. Migraine patients should be recommended not to exceed 200mg/day and, keep their caffeine drinking as consistent as possible to avoid withdrawal headache.

- •

Evaluate aspartame intake, as it has been described as a strong trigger for migraine and should be avoided.

- •

Temporo-mandibular joint (TMJ) review, if there is any clenching activity with TMJ dysfunction a dental splint might be helpful such as the nociceptive trigeminal inhibition tension suppression system (NTI-TSS) splint. Clenching frequently occurs in migraine patients and can often cause a sensation of ear fullness. TMJ disorders have been associated with migraine chronification.

- •

Several studies have tried to demonstrate the effectiveness of some alternative treatment. Among them it is worth mentioning magnesium (400–600mg/day) and riboflavin (400mg/day).13

- •

Proper head posture. Any activity, which promotes a head forward posture, will worsen symptoms, such as slumping forward at a low workstation.

- •

Physical therapy is an important modality in the management of headache symptoms, such as termed scapular stabilization and neck manipulations.

One of the most important aspects is to teach the patient to identify their migraine attacks because early treatment is essential to get an adequate response to end the attack. A stratified treatment must be carried out from the beginning, choosing the drug according to the severity of the symptoms, route of administration characteristics and comorbidity of the patient.

Migraine acute therapy can be divided into specific, non-specific and adjuvant treatments.

Non-specific acute treatmentThere is good quality evidence supporting the use of acetaminophen, nonsteroidal antinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), such as acetylsalicylic acid (ASA), ibuprofen, diclofenac, and dexketoprofen.14 These therapies can control mild migraine attacks and auras on their own. In the specific case of paracetamol (acetaminophen) is less potent and it may be a useful first choice drug for acute migraine in those with restriction to, or who cannot tolerate, NSAIDs or aspirin.15 It is generally only recommended in gestational migraine, during adolescence-childhood and in attacks without a severe level of disability.

Adjuvant medications are primarily antiemetic/neuroleptics Dopamine D2 receptor antagonists, (domperidone, metoclopramide, Chlorpromazine), that are necessary in patients with nausea or vomiting which also supports the absorption of the rest of the treatment.14 When using these treatments, you should monitor the potential extrapyramidal side effects and concern over potentially permanent tardive dyskinesia, sedation and orthostatic hypotension.

It is strongly recommended to avoid morphs and combinations of analgesics with barbiturates, codeine, tramadol and/or caffeine, because it is associated with headache chronification and development of medication overuse headache.16

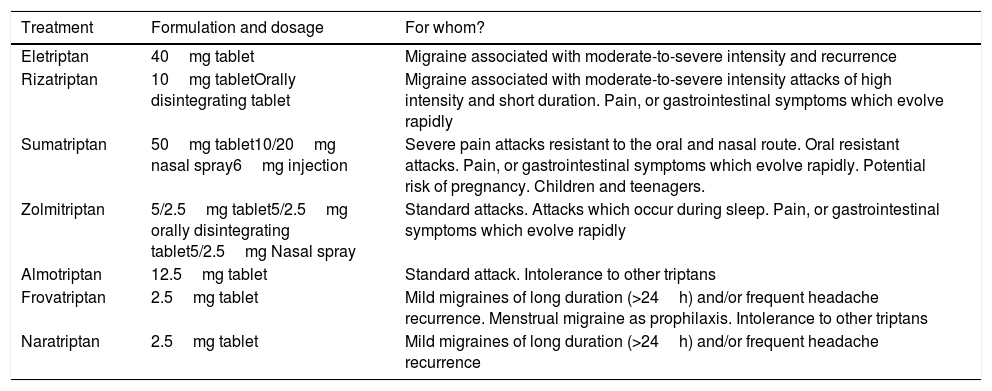

Specific acute treatmentThey are the drug of choice for a moderate-severe attack and every migraine patient should be prescribed a triptan. Triptans are specific migraine drugs with proven efficacy and safety in several clinical trials, however due to its vasoconstriction effect they are contraindicated in patients with uncontrolled hypertension, coronary, cerebrovascular and peripheral vascular disease.17 The most frequent side effects are palpitations, neck or chest tightness, dysgeusia, laryngeal discomfort and should always be warned to the patient when prescribed. Despite these effects, it should be pointed out that they are extraordinarily safe at the vascular level.18

There are 7 triptans currently available (Table 1) and the choice of one or the other must be individualized based on time of migraine onset (night or day), severity onset (rapidly or progressive), presence and timing of nausea or vomiting, levels of disability and frequency and pattern of attacks.19

Currently available triptans.

| Treatment | Formulation and dosage | For whom? |

|---|---|---|

| Eletriptan | 40mg tablet | Migraine associated with moderate-to-severe intensity and recurrence |

| Rizatriptan | 10mg tabletOrally disintegrating tablet | Migraine associated with moderate-to-severe intensity attacks of high intensity and short duration. Pain, or gastrointestinal symptoms which evolve rapidly |

| Sumatriptan | 50mg tablet10/20mg nasal spray6mg injection | Severe pain attacks resistant to the oral and nasal route. Oral resistant attacks. Pain, or gastrointestinal symptoms which evolve rapidly. Potential risk of pregnancy. Children and teenagers. |

| Zolmitriptan | 5/2.5mg tablet5/2.5mg orally disintegrating tablet5/2.5mg Nasal spray | Standard attacks. Attacks which occur during sleep. Pain, or gastrointestinal symptoms which evolve rapidly |

| Almotriptan | 12.5mg tablet | Standard attack. Intolerance to other triptans |

| Frovatriptan | 2.5mg tablet | Mild migraines of long duration (>24h) and/or frequent headache recurrence. Menstrual migraine as prophilaxis. Intolerance to other triptans |

| Naratriptan | 2.5mg tablet | Mild migraines of long duration (>24h) and/or frequent headache recurrence |

It is also possible to combined triptans with a NSAID or acetaminophen, or using alternative modes of administration such as injectables or nasal spray, may be associated with better outcomes than standard dose triptan tablets.20 If the first dose of triptan is not effective a second dose can be done after 1h within the first 24h. When using triptans, blood pressure should be monitored, since it can increase.

Triptans have a much better adverse effects and safety profile than ergotics which are currently disused drugs and should not be prescribed to newly diagnosed migraines.

New specific drugs for acute treatment have been developed in the recent years. Lasmiditan is a 5HT1F receptor agonist (unlike the triptans, which agonize the 5HT1B/1D receptors) available in the United States of America and soon expected to be approved in Europe. Their best advantage in comparison with triptans are that, by not having effect over 5HT1B receptors, they do not provoke vasoconstriction. Their efficacy has been proved in two clinical trials. The most important adverse event is somnolence, so patients should cautioned not to drive within 8h after taking lasmiditan.

Another new pharmacological group for acute therapy are gepants, which act as CGRP receptor antagonists. Such as lasmiditan, gepants do not cause vasoconstriction. Ubrogepant and Rimegepant has been approved by the FDA, their most common adverse event is nausea.

Prophylactic migraine treatmentPreventive treatment is used to reduce the frequency, duration, or severity of migraine attacks, making them easier to control with acute treatment. Ultimately, the goal is to improve quality of life and reduce the impact of migraine on patient functionality.

Preventive medications form the basis of headache management and should be considered in the following cases16,21:

- 1.

Frequent headaches (four or more attacks per month or eight or more headache days per month)

- 2.

Failure, contraindications, side effects or abuse of acute medications

- 3.

Patient preference

- 4.

Presence of prolonged auras such as hemiplegic migraine, brainstem aura because they do not usually respond to acute treatment

- 5.

Impact on the patient's quality of life and interference in their daily life despite correct treatment with lifestyle modification strategies and acute treatment of migraine

- 6.

Menstrual migraine

Migraine treatment should be individualized based on patients’ comorbidities, preference, lifestyle, age, and gender. The choice of which medication to use is made between the patient and the physician after considering all the side effects and efficacy.

A preventive migraine drug is considered successful if it reduces migraine attack frequency or days by at least 50% within 3 months.22

Basic principles of preventive treatment of migraine16,22,23:

- a)

Start the treatment at a low dose and increase it slowly until therapeutic effects develop, the ceiling dose is reached, or adverse events become intolerable.

- b)

The chosen treatment should be maintained for a minimum of 3 months and generally after 6–12 months try to withdraw the drug slowly.

- c)

It is important to warn patients that treatments often take (up to a month and a half) to start working.

- d)

In women of childbearing age avoid those teratogenic drugs

- e)

Set realistic expectations for improvement and adverse effects from treatment.

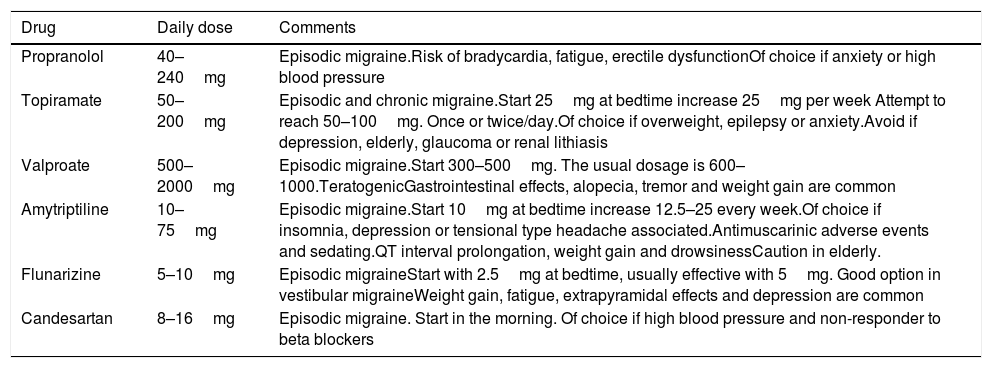

Oral drugs for migraine prophylaxis include the following therapeutic groups: antiepileptics, antidepressants and Blood pressure medications (see Table 2).

Most used prophylactic treatments for migraine.

| Drug | Daily dose | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Propranolol | 40–240mg | Episodic migraine.Risk of bradycardia, fatigue, erectile dysfunctionOf choice if anxiety or high blood pressure |

| Topiramate | 50–200mg | Episodic and chronic migraine.Start 25mg at bedtime increase 25mg per week Attempt to reach 50–100mg. Once or twice/day.Of choice if overweight, epilepsy or anxiety.Avoid if depression, elderly, glaucoma or renal lithiasis |

| Valproate | 500–2000mg | Episodic migraine.Start 300–500mg. The usual dosage is 600–1000.TeratogenicGastrointestinal effects, alopecia, tremor and weight gain are common |

| Amytriptiline | 10–75mg | Episodic migraine.Start 10mg at bedtime increase 12.5–25 every week.Of choice if insomnia, depression or tensional type headache associated.Antimuscarinic adverse events and sedating.QT interval prolongation, weight gain and drowsinessCaution in elderly. |

| Flunarizine | 5–10mg | Episodic migraineStart with 2.5mg at bedtime, usually effective with 5mg. Good option in vestibular migraineWeight gain, fatigue, extrapyramidal effects and depression are common |

| Candesartan | 8–16mg | Episodic migraine. Start in the morning. Of choice if high blood pressure and non-responder to beta blockers |

Anti-convulsants that might provide benefit for migraine prevention include: topiramate, valproic acid, and gabapentin. There are many others, but the data of efficacy has not been well established in migraine patients for all others. Of this group topiramate is the most frequently used and the most efficacious.24 Topiramate has side effects that include cognitive difficulties, pins and needles sensation in the extremities, kidney stones, mood changes such as depression, visual changes such as acquired myopia, retinal changes and glaucoma as well as decreased appetite with potential weight loss. Valproic acid has many more side effects than any of the other options including weight gain, hair loss and acne.25 Because of the sides effects it should not be used as a first step.

Antidepressants, the most frequently prescribed is amitriptyline which can cause weight gain and drowsiness.22 The dose is gradually increased to a maximum of 1mg/kg/day. I typically use other antidepressants such as venlafaxine. This is started at 37.5mg a day and increased to at least 75mg a day. The BP should be monitored with this treatment, as this can cause increases in BP. Antidepressants can be used to prevent migraine even if there is no underlying depression.

Blood pressure medications: Beta/blockers are one of the most commonly used class of drugs in the preventive treatment of episodic migraine and are about 50% effective in producing a greater than 50% reduction in attack frequency. Of these, propranolol is the most evidence-based and widely used drug although it has the disadvantage of not being taken once daily like the other beta-blockers.26 Although the available evidence is limited, lisinopril and overall candesartan are effective for episodic migraine prevention and may be an option in those migraineurs who associate high blood pressure but have contraindicated the use of beta-blockers.27 According to the available evidence, from this pharmacological group, flunarizine, a non-specific calcium channel blocker, is the only effective treatment in the prophylaxis of episodic migraine.28

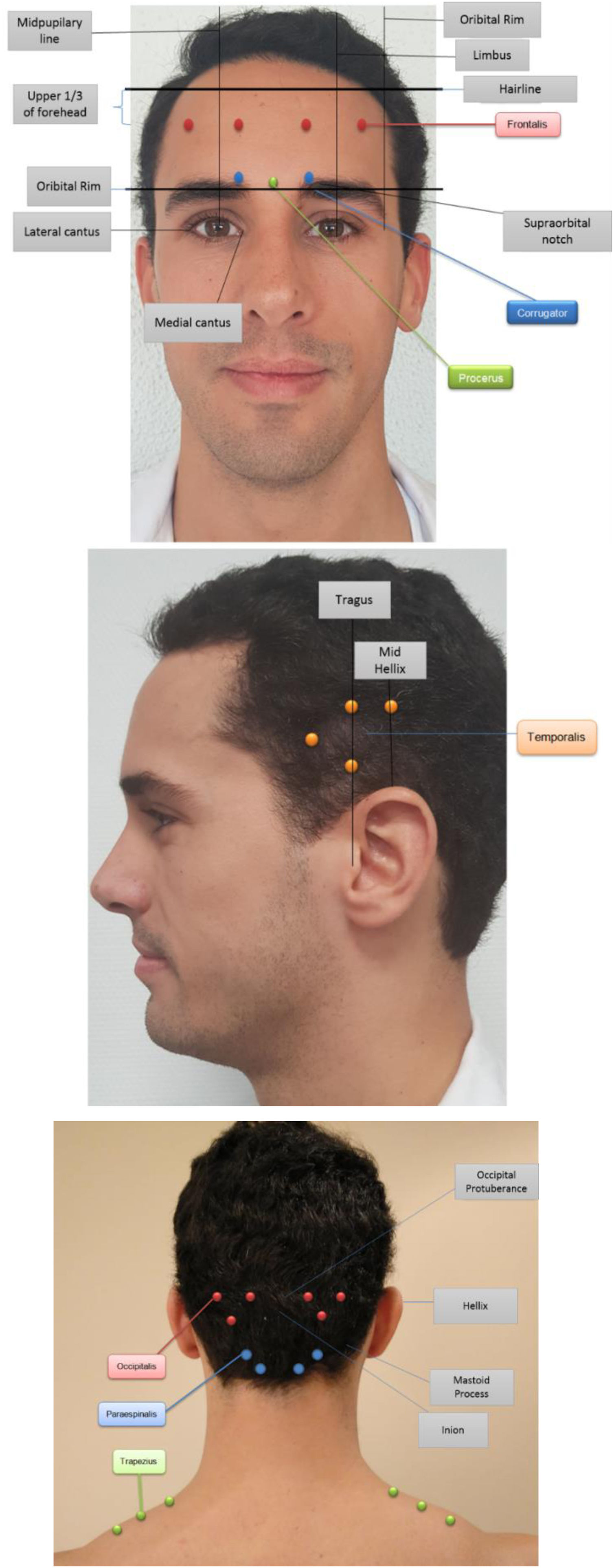

Treatment options managed by neurologistOnabotulinumtoxinA (Botox®) can only be considered in patients with more than 15 headache days a month. The method of botox injections for chronic migraine is based on PREEMPT trials and it is very specific, there are 31 standard sites (155 units) and additional follow the pain sites (up to an additional 40 units)29 (Fig. 2).

The total dose of Botox would be 195 units (5 units at each site with a 2-cc dilution per 100 units). These injections need to be done by a neurologist who is an expert in the administration of botox for chronic migraine. Incorrect injection technique will result in increased adverse events including droopy eyelids (ptosis), worsening headache and increased neck pain with possible neck weakness. These injections need to be done every 12 weeks to maximize the effect. There should be a minimum of three treatments to assess for effect and if helpful these treatments should then be continued every 12 weeks until the headaches have gone.

Erenumab (Aimovig®), Fremanezumab (Ajovy®), Galcanezumab (Emgality®) and Eptinezumab (Vyepti®) were released in the US in the last years after the positive results obtained in the clinical trials.30 These are monoclonal antibody (mAb) directed against Calcitonin Gene Related Peptide (CGRP) or its receptor which have a low side effect profile and are efficacious in migraine prevention. CGRP is the main chemical secreted from nerve endings in the brain during a migraine attack and is responsible for many of the migraine symptoms. These are self-administered subcutaneous injections once a month and for Fremanezumab once every 3 months or monthly too. Eptinezumab (Vyepti®) which also binds to CGRP ligand is the only that is given intravenously every 12 weeks. During the clinical trials a very low incidence of adverse events were reported and most common reported were injection site erythema, injection site induration, diarrhea or constipation, nasopharyngitis, upper respiratory tract infection. Cardiovascular risks are the main concern, but a recent study focusing on erenumab use in patients with known coronary artery disease failed to show an increase in myocardial infarction or angina. Real-world-evidence series confirm the good profile of effectiveness and safety observed in clinical trials.

It takes 3–6 months of continuous treatment to assess for response and like other preventive drugs it should be administered for 6–12 months depending on the evolution of the patient.

Peripheral nerve blocks31: Based on the limited evidence available, serial great occipital nerve peripheral block may be a preventive treatment for chronic migraine (CM). They have also been shown to have an immediate symptomatic effect on aura and pain. It is necessary to emphasize that, in the light of the available results, the addition of corticoid to the anesthetic has not demonstrated to be more effective reason why only BA should be considered. Other nerves like supraorbitary, occipital, auriculotemporal and maxillary could also be blocked.

Regarding an entity, such as gestational migraine, it should be highlighted that there are studies that support its use and it is a practice that is increasingly extended both at a symptomatic and preventive level. It should be highlighted that only lidocaine (category B of the FDA) should be used with respect to other anesthetics.

The medications that have the best evidence for efficacy in Chronic Migraine are: topiramate, onabotulinumtoxin type A and monoclonal antibodies directed against CGRP (Erenumab, Fremanezumab, Galcanezumab and Eptinezumab).

Referral neurologist criteria32- •

Diagnosis doubts

- •

Treatment failure

- •

Headache due to abuse of analgesics (provided that the primary care levelis not able to solve it).

- •

Migraine that does not improve despite at least one attempt preventive therapy (migraine with severe attacks, etc.).

- •

Patient with obvious distrust of the primary care level.

- •

Migraine with atypical or prolonged auras.

- •

Chronic migraine.

No external funding.

Conflict of interestNone declared.