Introducción: Los pacientes pediátricos con hidrocefalia y sistemas de derivación ventriculoperitoneal (válvula de derivación ventriculoperitoneal [VDVP]) no están exentos de padecer enfermedades gastrointestinales. En la actualidad, con los avances tecnológicos, sería controvertido no ofrecerles los beneficios de la cirugía de mínima invasión. A la fecha no hay estudios comparativos entre las diferentes técnicas que permitan evaluar cuál es la mejor forma de evitar la hipertensión endocraneal. Sin embargo, existen cada vez más reportes de cirugía segura en niños con VDVP operados por laparoscopia.

Caso clínico: Se presenta el caso de una colecistectomía laparoscópica en un paciente masculino de 14 años de edad con un sistema de VDVP que presentó datos clínicos de colecistitis. La evolución del paciente fue satisfactoria, y causó alta hospitalaria a las 72 h de la cirugía.

Conclusiones: Actualmente son comunes los casos de niños con hidrocefalia y sistemas de VDVP que requieren de alguna cirugía laparoscópica. Esta cirugía resulta segura para diversos procedimientos, incluyendo patología vesicular y de ovario. Los resultados satisfactorios ayudarán al cirujano a tomar una mejor decisión quirúrgica en este tipo de pacientes pediátricos.

Background: Pediatric patients with hydrocephalus and ventriculoperitoneal (VP) shunt systems are not exempt from suffering from gastrointestinal diseases. Today, with technological advances it would be controversial to not offer the benefits of minimally invasive surgery. To date, no studies have been carried out comparing different techniques to assess the best way to prevent intracranial hypertension. However, there are increasing reports of safe surgery in children with VP shunt operated by laparoscopy.

Case report: We present the case of a 14-year-old male who presented for laparoscopic cholecystectomy with a VP shunt system. The patient had clinical data of cholecystitis; therefore, it was decided to perform laparoscopic cholecystectomy. The patient experienced a satisfactory evolution with hospital discharge at 72 h postoperatively.

Conclusions: Currently, it is common that children with hydrocephalus and VP systems may require some type of laparoscopic surgery. This surgery is safe for various procedures including gallbladder and ovarian pathology. Satisfactory results will help the surgeon make a better surgical decision in this type of pediatric patient.

1. Introduction

Pediatric patients with hydrocephalus and ventriculo– peritoneal (VP) shunt are not exempt from suffering from gastrointestinal diseases that require a laparoscopic procedure for its resolution. There are reports of risk of CO2 diffusion via the VP shunt, with a subsequent increase in intracranial pressure during the surgery. Currently, with the technological advances it would be controversial to not offer patients the benefits of minimally invasive surgery. To date there are no comparison studies between the different techniques that allow evaluating the best way to avoid endocranial hypertension. However, increasingly there are more reports found in the literature about the safety of the procedure in children with VP shunt operated laparoscopically. This paper reports on the case of a laparo scopic cholecystectomy in a patient with VP shunt.

2. Case report

We present the case of a 14-year-old male patient with history of ataxia and hydrocephalus secondary to brain stem tumor between the third and fourth ventricle and who had the neoformation resected and a VP shunt valve placed. The patient progressed satisfactorily during his neurosurgical follow-up with no reports of active tumor process. There was no hydrocephalus and VP shunt system was functional.

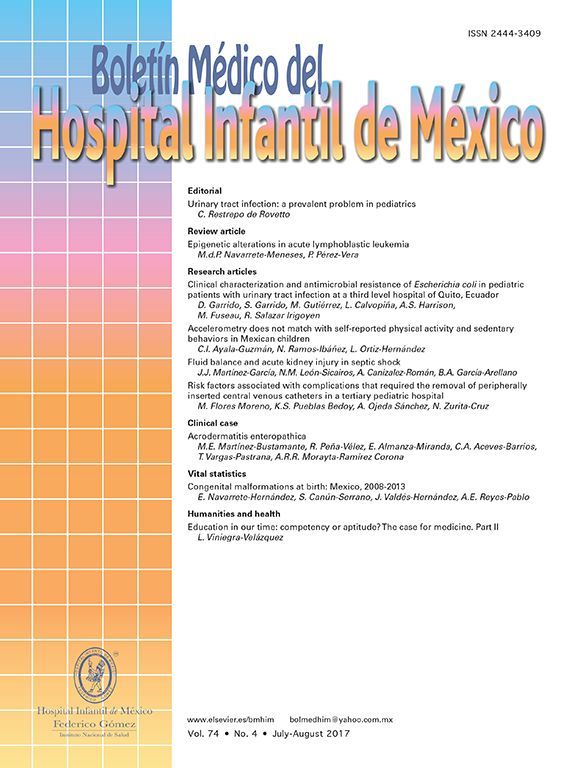

In March 2011 he was diagnosed with acute, nonperforated appendicitis. Open appendectomy was performed without complications. In August 2011 he was admitted to the emergency department with clinical data of cholecystitis. An ultrasound was performed showing gallstones. Intraand extrahepatic bile ducts were normal with thin walls and multiple bile stones and without data of acuity. Liver, pancreas and spleen were without abnormalities (Fig. 1).

Figure 1 Gallbladder ultrasound where gallstones are visualized.

The patient was scheduled for the surgical procedure. Pre-anesthesia examination was requested, and the patient was classified as ASA II due to the clinical picture and the surgical history. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy was decided upon based on literature evidence and on the consensus with the neurosurgery department. Under general balanced anesthesia it was proceeded to perform exteriorization of the VP shunt. Surgical time was 80 min, and insufflation pressures were maintained between 12 and 14 mmHg. Three 5-mm ports were placed and one 10-mm port at the level of the umbilicus using a 30 degree and 5-mm lens. The tip of the catheter of the VP shunt was visualized and exteriorized through an opening performed on the abdominal wall with a 5-mm working port, which was located in the right flank and removed when the tip of the catheter was exteriorized to avoid CO2 leaks or catheter dysfunction during the procedure. (Fig. 2).

Figure 2 Tip of the ventriculoperitoneal bypass system exteriorized via one of the 5-mm ports.

The tip of the catheter was left to drain inside a collection bag during the procedure, all under sterile conditions. It was decided to use the exteriorization technique of the tip of the VP shunt as it is a simple technique that allows drainage of the cerebrospinal fluid during the surgical procedure. By maintaining the tip of the catheter at atmospheric pressure, fluid dynamics are not altered and the risk of rupture of the catheter is decreased, which could occur when clamped.

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy was performed. It should be mentioned that there was an incident during extraction of the gallbladder through the abdominal wall. The gallbladder ruptured with drainage of bile and stones into the abdominal cavity. Washing of the surgical bed was done with physiological solution along with aspiration of the abdominal cavity and stone extraction. Once the cholecystectomy was completed under direct vision the catheter was reintroduced into the abdominal cavity. Under visual control each of the ports was removed without complications.

During the postoperative period the patient was maintained with analgesics for good pain control. For antibiotic coverage, it was decided to initiate with ceftria xone and amikacin. The prophylaxis was started 1 h after surgery and was maintained with IV antibiotics for 72 h due to the latent risk of a catheter infection. The patient progressed without fever. No complications related to the procedure were reported. The patient was discharged at 72 h postoperative in improved condition. Histopathological report showed a chronic cholecystitis and cholelithiasis.

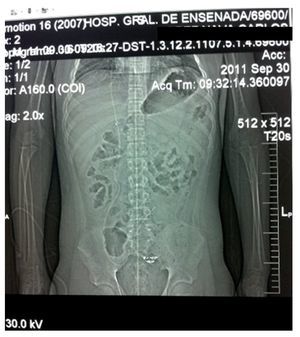

The patient was discharged with paracetamol for analgesia and amoxicillin with clavulonic acid orally for 7 days as an outpatient. The patient was continued to be followed by the Pediatric Surgery Department (Fig. 3) without complications. On the other hand, the Neurosurgery Department reported no tumor growth and hydrocephalus being controlled with the catheter and functional ventriculoperitoneal bypass valve (Fig. 4).

Figure 3 Healed surgical wounds are shown during surgical follow-up.

Figure 4 Plain x-ray of the abdomen where the functional ventriculoperitoneal bypass system is seen in appropriate position.

3. Discussion

Laparoscopic surgery may increase the intracranial pressure (ICP) by different mechanisms such as cerebral arteriolar vasodilation by hypercapnia or the ingurgitation of the cerebral veins by increase in vena cava pressure. It has also been observed that the Trendelenburg position during some procedures causes elevation in the ICP. Similarly, the risk of dysfunction of the VP shunt increases when the catheter is clamped or when using insufflation pressures>16 mmHg during surgical procedures lasting>3 h. On the other hand, if the catheter valve is incompetent, it may increase the risk of air embolism or CO2 to the brain as well as to elevate the ICP in a retrograde manner. Elevations of ICP in these patients could cause severe neurological complications as a consequence of posterior brain herniation.1-4

In healthy patients these increases in ICP are temporary and normalized after 10 min from the insufflation. However, in patients with VP shunt, an increase in ICP could be more serious and long-lasting as the elevation in intraabdominal pressure. As well, possible obstruction of the tip of the catheter could make CSF drainage difficult. Today we know that if the drainage valve is competent, it can support pressures of up to 300 mmHg, much higher than the usual intraabdominal pressures of 12-14 mmHg for laparoscopy.2

Different techniques have been proposed with the goal of minimizing the risk of CO2 reflux due to the increase in intracranial pressure in this type of patient. Some techniques are to decrease the volumes of insufflation to avoid an abrupt rupture with elevated pressures of pneumoperitoneum. For this, it is suggested to gradually increase the volumes and to maintain pressures of insufflation <16 mmHg. Also, laparoscopic procedures <3 h of duration should be performed. There are a high number of publications that address the functionality of laparoscopic procedures in patients with VP shunt if, and when, normal safety procedures are followed. For example, the length of time that the patient has with the VP shunt must be taken into consideration because the longer the VP shunt has been in place, the greater the possibility that it may not function properly. It has also been proposed to exteriorize the tip of the VP shunt during the laparoscopic procedure, which offers several advantages over maintaining the tip of the catheter IP during the laparoscopic procedure. By exteriorizing the tip of the catheter there is no need to clamp the catheter. There is also no need for lowering the insufflation volumes. There is no risk of the valve being dysfunctional or that it will not function during surgery. It is very important to maintain strict asepsis and antiseptic measures on the patient’s skin to decrease the risk of postoperative catheter infection. Once the procedure is completed, the catheter can be reintroduced in the abdominal cavity.1-7

Manipulation of the VP shunt laparoscopically implies a risk of infection similar to open surgery, for which strict control measures of asepsis and antisepsis are necessary as well as the adequate use of prophylactic antibiotics. On the other hand, the possibility of converting laparoscopic surgery to an open procedure should always be kept in mind when the adhesions do not allow for a safe laparoscopic surgery for the patient.7,8

Laparoscopic surgery has also been used for correcting some complications secondary to VP shunt such as disconnection of the distal segment of the VP shunt at the IP level, cutting the catheter when it is very long and is not functioning. Abscesses or peritonitis may be drained and peritoneal washing can be done laparoscopically as well as debridement and drainage of pseudocysts and inguinal hernias, common in these patients due to the increase in intraabdominal pressure and can be corrected with a laparoscopic inguinal herniorrhaphy.3-5

Today it is common for pediatric surgeons to be faced with cases of children with hydrocephalus with VP shunt and who require some type of laparoscopic surgery: Nissen fundoplication with or without gastrostomy and gallbladder or ovarian disease are procedures that can be carried out safely laparoscopically. For this reason the publication of cases such as this one is important. Together with what has already been published by other authors in the last 10 years helps to make a better surgical decision in pediatric patients who have a VP bypass valve and who are going to be subjected to a laparoscopic procedure.

Ethical disclosures

Protection of human and animal subjects. The authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this investigation.

Confidentiality of Data. The authors declare that no patient data appears in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consent. The authors must have obtained the informed consent of the patients and /or subjects mentioned in the article. The author for correspondence must be in possession of this document.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest of any nature.

Received 4 March 2014;

accepted 17 September 2014

* Corresponding author.

E-mail: wwwilver@hotmail.com (W.E. Herrera García).