The treatment of cutaneous melanoma has historically been essentially surgical. Much progress has been made in this area, and the resection margins have been established based on tumour depth. Candidates are also identified for lymphadenectomy, avoiding the morbidity of the procedure in patients who do not require it. But little progress has been made in systemic treatment, since the 70's when the use of dacarbazine was introduced for the treatment of patients with tumour progression or distant metastasis, with disappointing results. Despite this, dacarbazine has been the most used drug to the present.

Three years ago, two new drugs were introduced, one of them based on the target therapy and other one in the immunotherapy, offering, with the obtained results, an alternative in the treatment of cutaneous melanoma.

The objectives of this article are to show the pathways of these drugs, to describe the current role of surgery in cutaneous melanoma, with the arrival of these drugs, as well as to know the therapeutic alternatives that are emerging for the cutaneous melanoma based on scientific evidence.

El tratamiento del melanoma cutáneo ha sido, históricamente, esencialmente quirúrgico. Muchos progresos se han hecho en esta área: se han establecido los márgenes de resección con base en la profundidad del tumor y, se han identificado pacientes candidatos a linfadenectomía, evitando así la morbilidad del procedimiento en pacientes que no la requieren. Pero en el tratamiento sistémico se han hecho escasos progresos: desde los años setenta se introdujo el uso de la dacarbazina para el tratamiento de los pacientes con progresión tumoral o metástasis sistémicas, pero los resultados han sido decepcionantes; a pesar de ello, la dacarbazina ha sido la droga más utilizada hasta la actualidad.

Hace 3 años, 2 nuevas drogas fueron introducidas, una de ellas basada en la terapia blanco y la otra en la inmunoterapia, ofreciendo una alternativa en el tratamiento del melanoma cutáneo.

Los objetivos de este manuscrito son: mostrar las vías de acción de estos medicamentos. Describir cuál es el papel actual que tiene la cirugía en el tratamiento del melanoma cutáneo con la llegada de estas drogas, y conocer qué alternativas terapéuticas están surgiendo para el tratamiento sistémico del melanoma cutáneo con base en la evidencia científica.

Since 1971, dacarbazine has been the standard treatment for patients with systemic inoperable metastases of malignant melanoma.1 It produces global responses in approximately 15% of patients, but in only 4% the disease disappears, and in those with full response the interval free of disease is very short; the mean recurrence is 3–6 months.

Recently, a great variety of effective drugs for the treatment of bronchogenic cancer, breast cancer, colorectal cancer and other tumours have appeared, turning the treatment of these neoplasms into a multidisciplinary exercise; while for cutaneous melanoma the treatment is still within the field of only one discipline: surgery.

The progress in the treatment of other neoplasms has far overtaken that of melanoma. Cutaneous melanoma has proven to be, more than other neoplasms, insensitive to the various systemic therapies and radiotherapy. This may be due to the fact that the cells from which melanoma originates are designed to protect it against the damages of DNA caused by the sun, and are located in the skin, where they are exposed to the damage caused by UV rays on the DNA. These cells seem to have the ability to defend themselves when exposed to cytotoxic drugs, similarly to how they do in the hostile environment where they normally develop.

This does not mean that there have been no developments in the therapy of cutaneous melanoma; substantial developments have been made in the understanding of the behaviour of this neoplasm and its surgical treatment. Resection margins were substantially reduced based on solid scientific evidence; it was proved that prophylactic lymph node dissection and regional perfusion were not useful and these were abandoned; lymphatic mapping with biopsy of sentinel lymph node was introduced, and it was proved that it improved staging, which offered valuable information for the prognosis, which in selected patients avoided unnecessary morbidity caused by lymph node dissection, and that it improved the survival of patients with a positive sentinel lymph node.2

In the staging and diagnosis, it was proved that positron emission tomography improved the staging of patients with advanced disease. As a result of these developments, the treatment of malignant melanoma became more individualised and survival rates improved; however, melanoma experts are still waiting for a really effective drug for the systemic treatment of patients with systemic disease.

Changes arrived in 2010, when there were 2 relevant developments in systemic therapy: targeted therapy and immunotherapy.

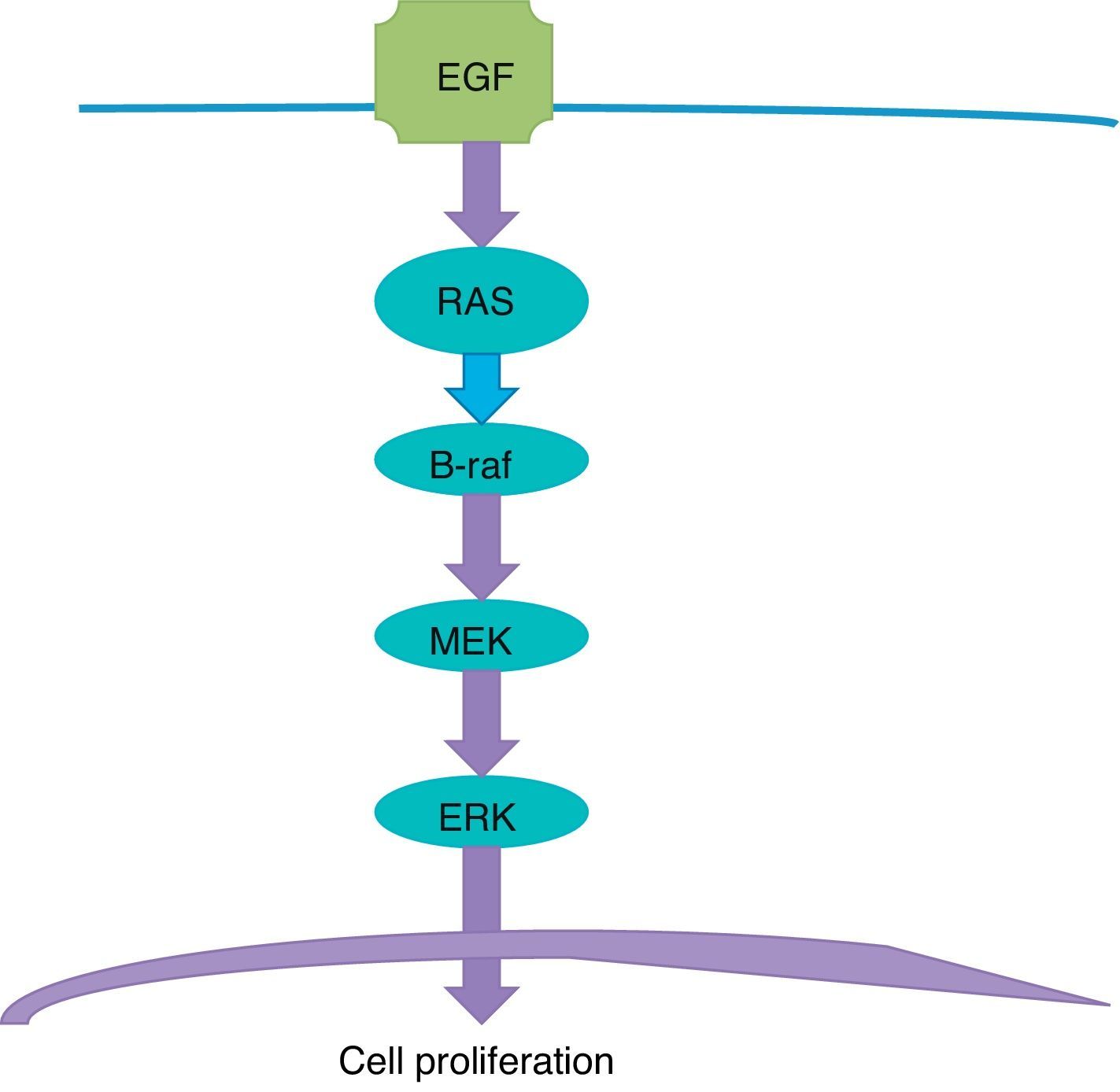

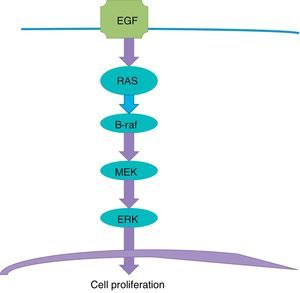

Targeted therapyTargeted therapy is related to the tyrosine-kinase pathway, also known as MAP Kinase pathway or MAPK signalling pathway (Fig. 1). This pathway begins in the cellular membrane and follows several steps until reaching the nucleus. The receptor of the epithelial development factor receives the signal to stimulate the development and activate the RAS protein. The RAS protein activates the B-Raf protein, which in turn activates the MEK protein (also known as MAPK), which makes the ERK stimulate the genes in the nucleus that are responsible for cellular development and proliferation. This is a physiological process responsible for cellular proliferation when necessary, and which stops when it is not necessary.

The problem arises where there is a mutation in the gene that is responsible for producing the B-Raf protein. In the DNA chain, an adenine is replaced with a thiamine; as a consequence, a valine amino acid of the B-Raf protein sequence is replaced with glutamic acid in the 600 codon amino acid; this is the origin of the name of the V600E mutation. The result is a B-Raf aberrant protein which loses the ability to “turn off” or “stop”, and this translates into persistence of stimulation of MEK, and this, in turn, continues to stimulate the ERK, which stimulates the genes that perpetuate cellular proliferation; the end result is a cancerous cell which continues to divide. The mutation of the BRAF gene is present in half of all melanomas.

A small molecule called vemurafenib joins the malicious B-Raf V600E protein and makes it ineffective, the cellular proliferation stops and tumour cells go into apoptosis.

Several studies proved that this molecule is effective against cutaneous melanoma; a phase III clinical trial which included 675 patients with inoperable stages IIIC and IV melanoma who had B-Raf V600E mutation and vemurafenib was compared with dacarbazine; an intermediate analysis was published after a mean follow-up of 3.8 months of patients in the vemurafenib group.3 The response was impressive in the vemurafenib+dacarbazine group vs. dacarbazine only: 48% vs. 5% (p<0.001).

Responses to vemurafenib are very fast, and some patients feel an improvement a few days after starting treatment. In this study, 2 patients had full response (0.9%), with a survival mean of 9.2 months in the experimental arm and 7.4 months in the control arm; patients obtained an improvement in overall survival of 7 weeks.

Unfortunately, the responses are not lasting; the mean duration of the response is 6 months and, with rare exceptions, all patients eventually relapse or progress.

At The Netherlands Cancer Institute, more than 100 patients received this treatment and only one had an interval free of disease of 1.5 years.

The problem is that melanoma quickly becomes resistant to vemurafenib and develops several pathways to block its effect.

Vemurafenib is associated to important morbidity, such as photosensitivity, arthralgia, rash, fatigue, alopecia and an easier development of dermic neoplasms, mainly keratoacanthoma and epidermoid carcinoma. The extensive side effects of vemurafenib show that it not only affects neoplastic cells and that the connotation “targeted therapy” may be an exaggeration; in Mexico, the results with the treatment of patients with cutaneous melanoma with vemurafenib are still to be reported; in the United States of America the cost of the treatment with this medication is US$9400 a month.

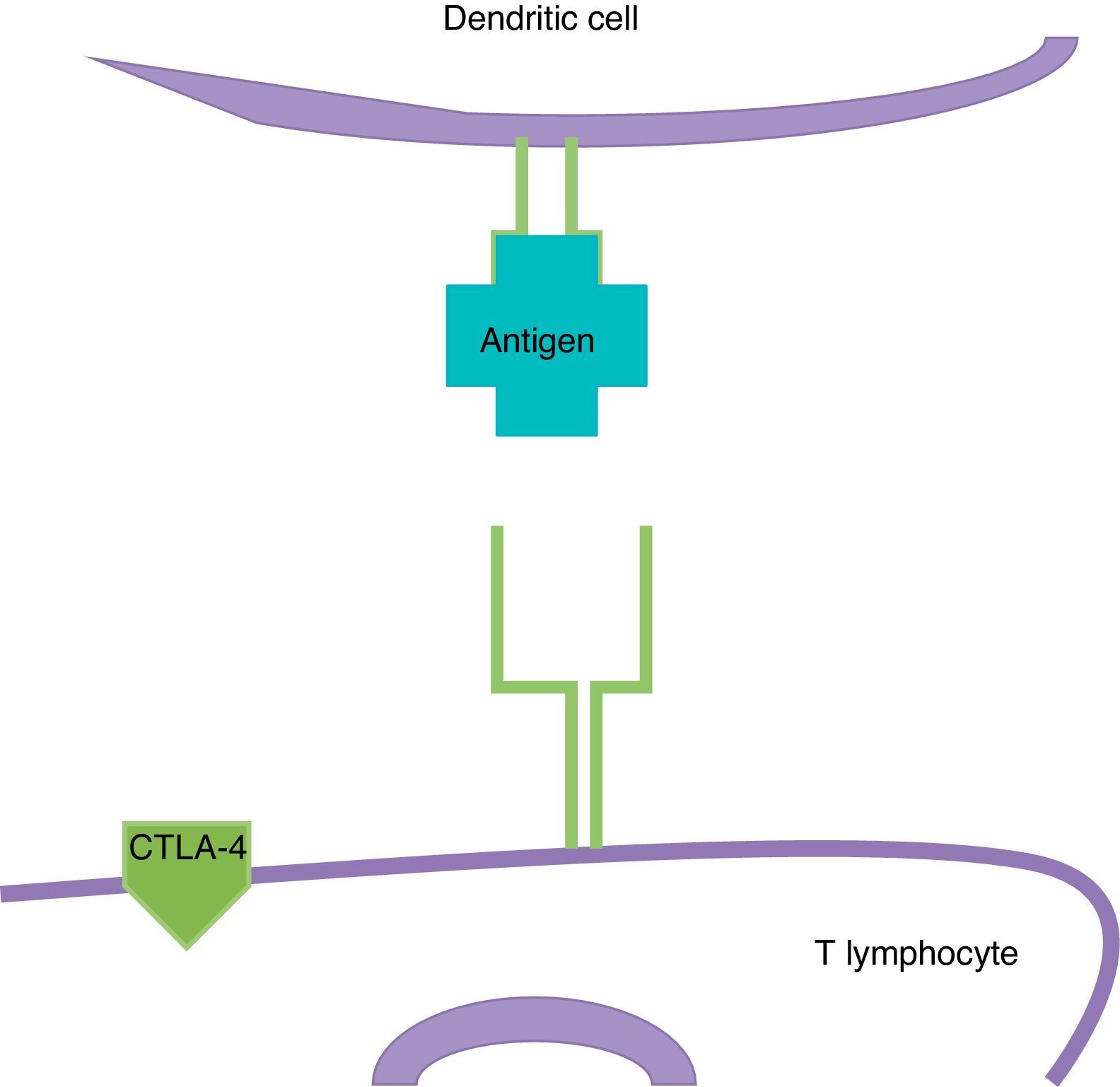

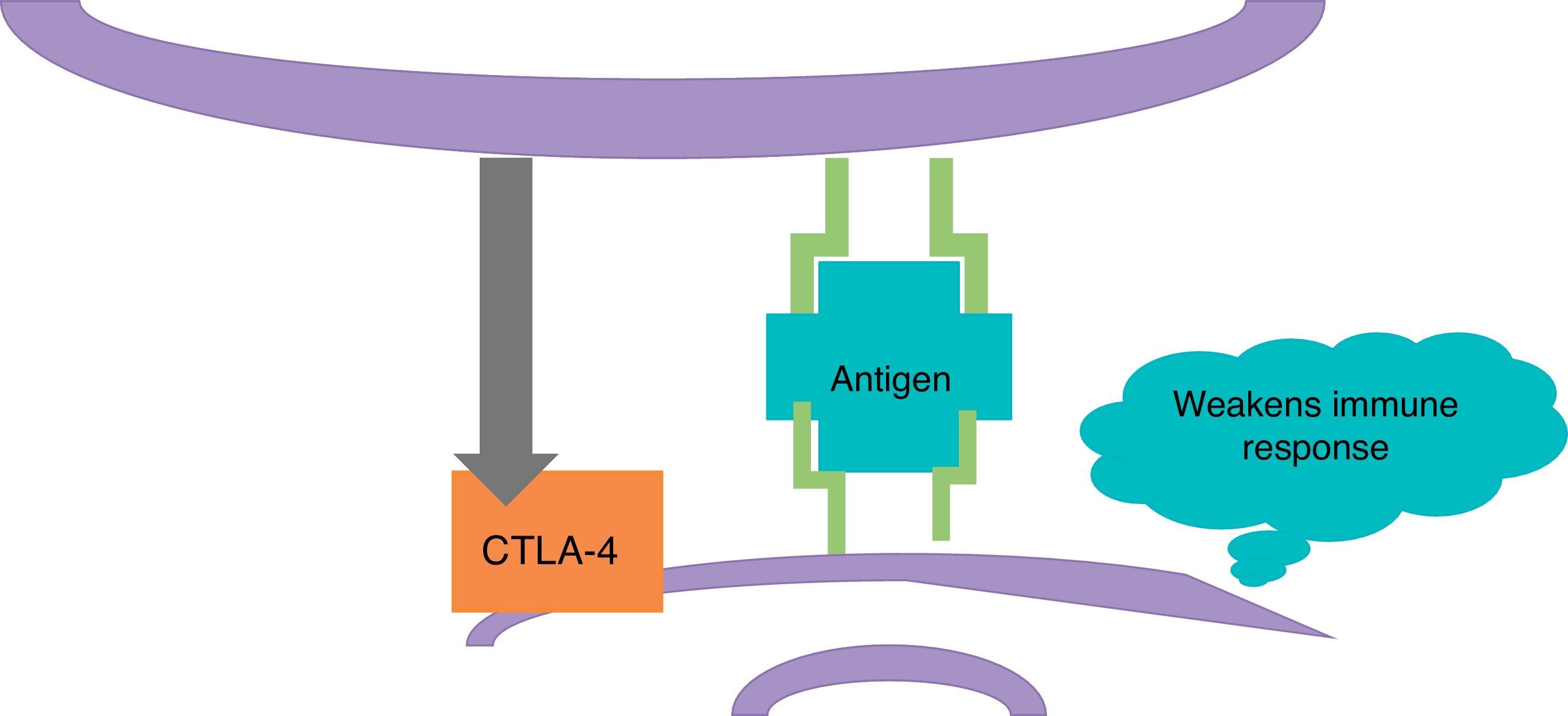

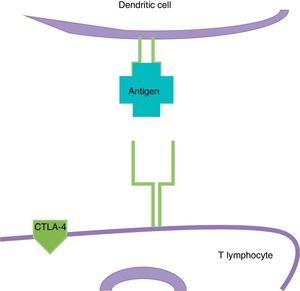

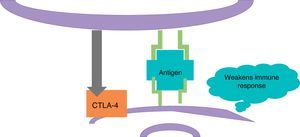

ImmunotherapyDendritic cells present the antigen of melanoma to T lymphocytes (Fig. 2); these reach the tumour and kill neoplastic cells. Once the immune response is activated, dendritic cells activate cytotoxic T lymphocytes associated to the cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA-4); these have the role of regulating the activity of the immune response in the sense that they decrease the activity of T cells and their proliferation (Fig. 3). This is a physiological mechanism which prevents the immune response from over-activating and prevents the immune system from attacking the tissues of the organism; CTLA-4 creates a balance in the activity of the immune response.

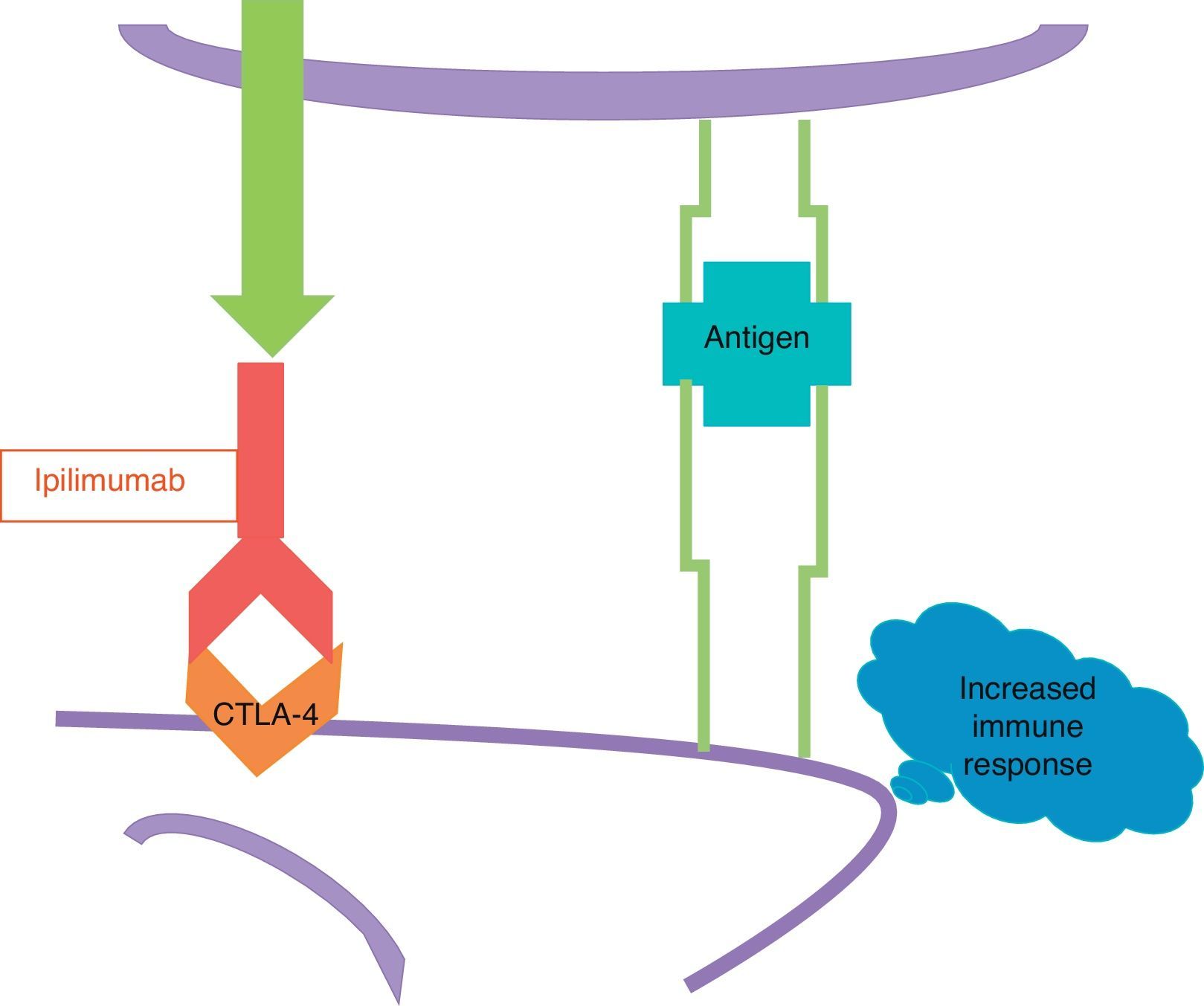

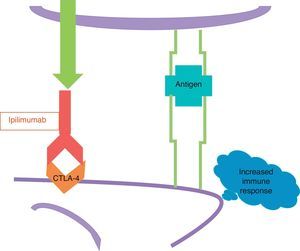

The other new drug is ipilimumab, a human monoclonal antibody which fixes to the CTLA-4. Ipilimumab blocks CTLA-4 and prevents it from activating (Fig. 4); in other words, it removes the brake that an activated CTLA-4 applies to the immune response, and as a result the immune response increases.

Ipilimumab does not attack the cells of the melanoma directly, which is why it is not a targeted therapy as vemurafenib, but rather stimulates the immune response in general, including the existing immune response against melanoma.

In a phase III study,4 502 patients were randomised with stages III and IV metastatic inoperable melanoma in 2 groups; one received ipilimumab plus dacarbazine, and the other dacarbazine plus placebo. The response was 15% in the group of ipilimumab and 10% in the control group; this difference was not significant.

In contrast to vemurafenib, which acts fast, the response to ipilimumab is slow, it takes approximately 3 months to become evident; there may even be a period when the tumour grows, and this happens when T lymphocytes infiltrate the tumour.

In the study mentioned, 4 patients in the ipilimumab group had full response (1.6%) and 2 in the control group (0.8%), global survival was significantly better in the group receiving ipilimumab plus dacarbazine than in the group receiving dacarbazine plus placebo after 3 years: 21% vs 12% (p<0.001); ipilimumab increased the survival by 9 weeks.

This treatment causes serious morbidity, especially in the digestive tract; 56% of patients treated with ipilimumab plus dacarbazine presented grade 3 or 4 toxicity related with the immune response; there were no deaths related to the treatment or gastrointestinal perforations in the experimental group, but a previous study5 had previously reported intestinal perforations and 2.1% mortality associated to the treatment; in the United States of America the price of the drug is $120,000 dollars for 4 doses.

DiscussionVemurafenib and ipilimumab have logically made all professionals dedicated to melanoma around the world be expectant. Are these 2 original drugs, the great advance we have been waiting for many years?

In our opinion, the response is ambiguous: yes and no; we would be tempted to say no because these 2 drugs are not necessarily the great advance we have been waiting for; neither patients nor their doctors are too thrilled when they are told that the full response ranges from 0.9 to 1.6%, or when they are told that survival may be increased by a few months at the expense of a considerable morbidity.

To make these percentages familiar in a perspective that surgeons are more familiarised with: lymphatic mapping with biopsy of the sentinel lymph node, with subsequent lymph node dissection in the event of positive sentinel lymph node, improves full response in 19% and for at least 10 years, a percentage of a different magnitude than that offered by drugs.

Vemurafenib and ipilimumab must not be viewed with the same suspicion as previous drugs promoted as the great advance in the treatment of melanoma, since these 2 new drugs are revolutionary at the basic science level.

Vemurafenib acts near the genetic mutation, which is the basis of the alteration in the neoplastic cell; unfortunately, the correction of the defect in only one aberrant gene is not enough to stop the proliferation of melanoma for more than a few months. There are more than 30,000 genetic mutations in the melanoma cell. Are there patterns of mutations and genetic aberrations we may block? Researchers are working on new drugs acting at different levels of the tyrosine-kinase pathway, the combination of dabrafenib and trametinib act both on B-Raf as on MEK; this seems to be the most promising approach.

In the past, 35% of patients with stages III and IV melanoma had a survival of one year. This percentage has improved to 76% with the combined regime6; maybe this combination may have the sustained effect that vemurafenib is lacking and may avoid melanoma from becoming resistant so quickly.

Relation of the metastatic surgery and vemurafenibThis drug is of great relevance and importance for surgeons. The response it causes offers an interesting chance for patients with large growth of non-resectable metastatic tumours with mutation of V600 BRAF: half of patients respond, and although most do not have a full response and the response does not last, the speed of the response may offer an advantage in the time to operate and resect an initially inoperable tumour which, due to the response to the treatment, can be removed before it becomes resistant and begins to grow again; this phenomenon of downstaging seems to be an attractive option for patients with inoperable tumours at the beginning of the treatment, and may be an alternative to improve survival in patients with metastatic melanoma, mainly in M1A and M1B stages.

The weakness of ipilimumab is that it is not specific for melanoma and stimulates the immune response in general. The true importance of ipilimumab is the long term benefit for patients showing response or stability of the disease. The follow-up of cohorts of patients has proven that the full response may continue in some patients beyond 6 years. The impression is that survival to 5 years may be 20%. Many patients may have stable metastases and coexist for some time with their metastatic disease; this is, having a “chronic” oncologic disease.

ConclusionCutaneous melanoma has always been a surgical and largely monodisciplinary disease. It is when the patient presents distant metastases that he or she was sent to systemic treatment, dacarbazine was administrated, and the initially treating physician never saw the patient again. This has changed, currently there is targeted therapy, immunotherapy, adjuvant treatments and rescue surgery after almost successful systemic treatments; there is currently a direct interaction between the medical oncologist and surgical oncologist. The treatment of melanoma has therefore become multidisciplinary.

Will the new treatments change our surgical strategy in cutaneous melanoma? First we have to wait for long term results to know the real value of these drugs; we still remember studies of new drugs which showed improvements in the beginning, only to see that benefit disappear after long term follow-up.7–9 We also have to wait to know the potential side effects which may be seen after a longer follow-up period.

What would happen if these successful new drugs were tested in early stages of melanoma? In an adjuvant manner after dissection of lymph nodes for palpable disease for instance, but also—and why not?—in the cases of patients with metastatic sentinel lymph nodes, and even in patients with localised disease but known to have a bad prognosis, such as thick and ulcerated melanomas, which are those more frequently diagnosed in Mexico; studies which require, without a doubt, surgical support.

Many surgeons wonder if patients with cutaneous melanoma will be treated in the near future with systemic therapy instead of surgery. We think this is unlikely, and will continue to operate patients with stages iii and iv melanoma with resectable lesions; after all, no melanoma is resistant to formaldehyde.

The surgical treatment of patients with stages iiiand iv operable melanomas offers a survival of up to 10 years for 35%, substantially better than any optimistic survival we may achieve with any drug. The new drugs may even generate patients as candidates for surgery who were not so upon diagnosis, such as patients with initially inoperable metastatic melanomas, which become resectable after neoadjuvant systemic therapy, and stage IV patients who require clean up surgeries after successful systemic treatment; that multidisciplinary treatment may cause a growth in the number of patients with melanoma requiring surgery.

These are interesting times for professionals interested in cutaneous melanoma. The arrival of targeted therapy and immunotherapy improved the survival of patients with advanced disease. Although full responses are rare, these patients have to be evaluated in a multidisciplinary manner. Also, the basis of the new drugs does not seem to be very impressive; however, a better understanding of the molecular biology of the tumour and the immune system allow for the development of even more innovative drugs aimed specifically at the tumour or stimulating the immune system against the neoplasm.

The future had never been so bright in the therapeutic scenario of cutaneous melanoma, and we must be prepared to see the succession of amazing and wonderful events in years to come.

Surgeons can and will play an important role in the future treatment of melanoma and in research. Surgeons around the world must be encouraged to participate in studies to advance the field of treatment of melanoma and make the most of the advances made so far.

Conflict of interestWe declare there are no conflicts of interest, external financial support or commercial interest.

Please cite this article as: Nieweg OE, Gallegos-Hernández JF. La cirugía en melanoma cutáneo maligno y las nuevas drogas. Cir Cir. 2015; 83: 175–180.