Antibiotic prophylaxis is the most suitable tool for preventing surgical site infection. This study assessed compliance with antibiotic prophylaxis in surgery for acute appendicitis, and the effect of this compliance on surgical site infection.

Material and methodsProspective cohort study to evaluate compliance with antibiotic prophylaxis protocol in appendectomies. An assessment was made of the level of compliance with prophylaxis, as well as the causes of non-compliance. The incidence of surgical site infection was studied after a maximum incubation period of 30 days. The relative risk adjusted with a logistic regression model was used to assess the effect of non-compliance of prophylaxis on surgical site infection.

ResultsThe study included a total of 930 patients. Antibiotic prophylaxis was indicated in all patients, and administered in 71.3% of cases, with an overall protocol compliance of 86.1%. The principal cause of non-compliance was time of initiation. Cumulative incidence of surgical site infection was 4.6%. No relationship was found between inadequate prophylaxis compliance and infection (relative risk=0.5; 95% CI: 0.1–1.9) (P>0.05).

ConclusionsCompliance of antibiotic prophylaxis was high, but could be improved. No relationship was found between prophylaxis compliance and surgical site infection rate.

La profilaxis antibiótica es la herramienta más adecuada para prevenir la infección de la herida quirúrgica. En este estudio se evaluó el cumplimiento de la profilaxis antibiótica en la cirugía de apendicitis aguda, y el efecto del mismo en la infección de sitio quirúrgico.

Material y métodosSe ha realizado un estudio de cohorte prospectivo, para evaluar el cumplimiento del protocolo de la profilaxis antibiótica, en apendicectomías. Se evaluó el grado de cumplimiento de la profilaxis, así como las causas de incumplimiento. Se estudió la incidencia de infección de sitio quirúrgico, después de un periodo máximo de incubación de 30 días. Para evaluar el efecto del incumplimiento de la profilaxis de la infección del sitio quirúrgico, se utilizó el riesgo relativo ajustado con un modelo de regresión logística.

ResultadosEl estudio incluyó a un total de 930 pacientes. La profilaxis antibiótica estaba indicada en todos los pacientes, y se administró en el 71.3% de los casos, con un cumplimiento general del protocolo de un 86.1%. La causa principal del incumplimiento fue la hora de inicio. La incidencia acumulada de infección del sitio quirúrgico fue del 4.6%. No se encontró relación entre la adecuación de la profilaxis y la infección del sitio quirúrgico (riesgo relativo=0.5; IC 95%: 0.1–1.9) (p>0.05).

ConclusionesEl cumplimiento de la profilaxis antibiótica fue alto, pero puede mejorarse. No se encontró relación entre el cumplimiento de la profilaxis y la incidencia de infección del sitio quirúrgico.

Surgical site infection is the second cause of nosocomial infection and the most common cause of infection in surgical patients.1–3 Its incidence depends on the extent of contamination of the surgical procedure, and certain factors intrinsic and extrinsic to the patient4 and can vary from 1% in clean surgery to 20% or more in certain types of dirty surgery.5 Surgical site infection increases patient risk and severity and is significantly less in clean surgical procedures that have less bacterial contamination, less surgical trauma and less blood loss.6

A strategy of proven effectiveness for prevention and control of surgical site infection is the use of antibiotic prophylaxis2,7–9 to prevent the growth of micro-organisms in the surgical wound that can be produced due to contamination during the surgical act, from the interstitial space, fibrinous clots or haematomas.

The antibiotic used for antibiotic prophylaxis should reach optimal levels in the interstitial fluid and appropriate concentrations in serum, while fibrin or haematoma are in the process of forming. The main objective of antibiotic prophylaxis is to achieve high levels of the drug in the tissue during the surgical process and the hours immediately following closure of the incision. If the antibiotic used is sufficiently active against potentially contaminating micro-organisms and high levels of the drug are achieved during the entire surgical process, prophylaxis will generally be effective.10

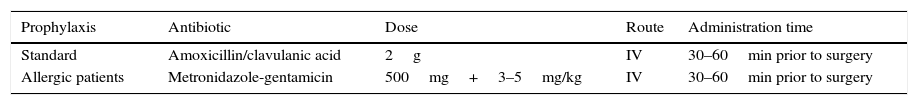

Our hospital has a protocol for administering antibiotic prophylaxis (Table 1) consistent with the directives reviewed in the literature, and the objective of our study was to evaluate compliance with this protocol in appendectomy patients and the effect of their adaptation on surgical site infection rates.

Material and methodsA prospective, cohort study was performed in the University Hospital Fundación Alcorcón of the Community of Madrid. The study included patients who had undergone appendicectomy in the General Surgery and Digestive System Unit, from 1 July 2007 to 30 June 2015.

The sample size was calculated according to a confidence level of 80%, power of 80%, infection rate of 2% in the group with adequate prophylaxis, and 5% in the group with inadequate prophylaxis, a compliance/non-compliance ratio of 3 and losses to follow-up of 5%.11 Based on these premises, a total study sample of 886 patients was considered necessary.

The approval of the Ethics and Clinical Research Committee and the Research Commission was gained in order to undertake the study. The patients were selected using a consecutive inclusion process at the time of the diagnosis of acute appendicitis, and they all signed their informed consent. Exclusion criteria were confirmed or suspected infection at time of surgery or having undergone antibiotic treatment the week prior to surgery. The Center for Disease Control12 diagnostic criteria were used to diagnose surgical wound infection. The micro-organisms causing the infection were identified by MicroScan Walkaway (Siemens®).

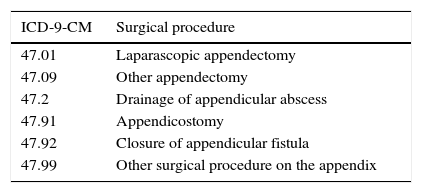

The variables studied were: age, gender, antibiotic, dose, administration route, prophylaxis administration time, duration of administration, start and end time of surgery, surgical procedures grouped under APPY according to the criteria of the Center for Diseases Control (Table 2), comorbidity, existence or absence of infection during follow-up period, type of infection (superficial incisional, deep incisional or organ/space) and the micro-organism causing the infection.

Surgical procedures studied according to the 9th Clinical modification International Classification of Diseases (ICD-9-CM).

| ICD-9-CM | Surgical procedure |

|---|---|

| 47.01 | Laparascopic appendectomy |

| 47.09 | Other appendectomy |

| 47.2 | Drainage of appendicular abscess |

| 47.91 | Appendicostomy |

| 47.92 | Closure of appendicular fistula |

| 47.99 | Other surgical procedure on the appendix |

A descriptive study was made of the sample, describing the qualitative variables with their distribution of frequencies (number and percentage), comparing them with Pearson's χ2 test. The quantitative variables are described with mean and standard deviation (SD). Normality was assessed with the Shapiro–Wilk test and compared with the non-parametric Mann–Whitney test.

The percentage of administration of antibiotic prophylaxis and compliance were assessed and compared with the administration guidelines indicated in the hospital's current protocol (Table 1). Adequate administration of antibiotic prophylaxis was defined as compliance with each of the administration criteria outlined in the protocol. The following reasons for failing to comply with prophylaxis were examined: duration (administration of more than one dose), choice of antibiotic (different to that established in the protocol), start time (administration more than an hour before incision), dose (different to that established in the protocol) and administration route (not intravenous). Given that the maximum infection incubation period for a surgical wound without implants is 30 days according to the Center for Disease Control, the incidence of surgical site infection during the 3 days following surgery was studied, regardless of whether the patients remained in hospital or had been discharged. In the case of the inpatients, surgical site infection was assessed by both a preventive medicine specialist and a surgeon. The patients who had been discharged had their wound infections assessed in the hospital's outpatient department, emergency department, their primary care centre through the Horus® application for accessing clinical histories or by a telephone call, if the patient had not attended any of the aforementioned health centres and if there were no records in their primary care history. The relationship between adhering to the antibiotic prophylaxis protocol and the incidence of surgical site infection was examined with the relative risk adjusted by the various covariates with a logistic regression model.

The data were collected on an ad hoc designed database. The data were recorded on a standardised, normalised and relational database created using Microsoft Access.® SPSS 19 software was used for statistical analysis and differences with p<0.05.were considered statistically significant.

ResultsA total of 930 patients were included in the study, 416 females (44.7%) and 514 males (55.2%). The overall mean age was 32.9 years (SD 21); 35.6 years (SD 12) for the females and 30.9 years (DE 14) for the males (p<0.05). The mean duration of the intervention was 60.3min (SD 38).

The type of procedure performed in the main was open appendicectomy (89%), followed by laparoscopic appendicectomy (10%), and drainage of appendicular abscess (1%).

Antibiotic prophylaxis administration was indicated in all the patients studied. Prophylaxis was given to 664 patients which was 71.3% compliance, it could not be recorded in 266 patients (28.7%). The antibiotics administered were amoxicillin/clavulanic acid (93.5%), metronidazole–gentamicin (1.5%), ceftriaxone (2%) and cefazolin with or without metronidazole (3%).

There was overall adherence to the protocol of 86.1% (572 patients) in patients receiving prophylaxis, taking into account all the adaptation criteria as a whole. Table 3 shows adaptation to the criteria of the hospital's prophylaxis administration protocol. The most common reason for failing to adhere to the protocol was the prophylaxis start time followed by the choice of antibiotic.

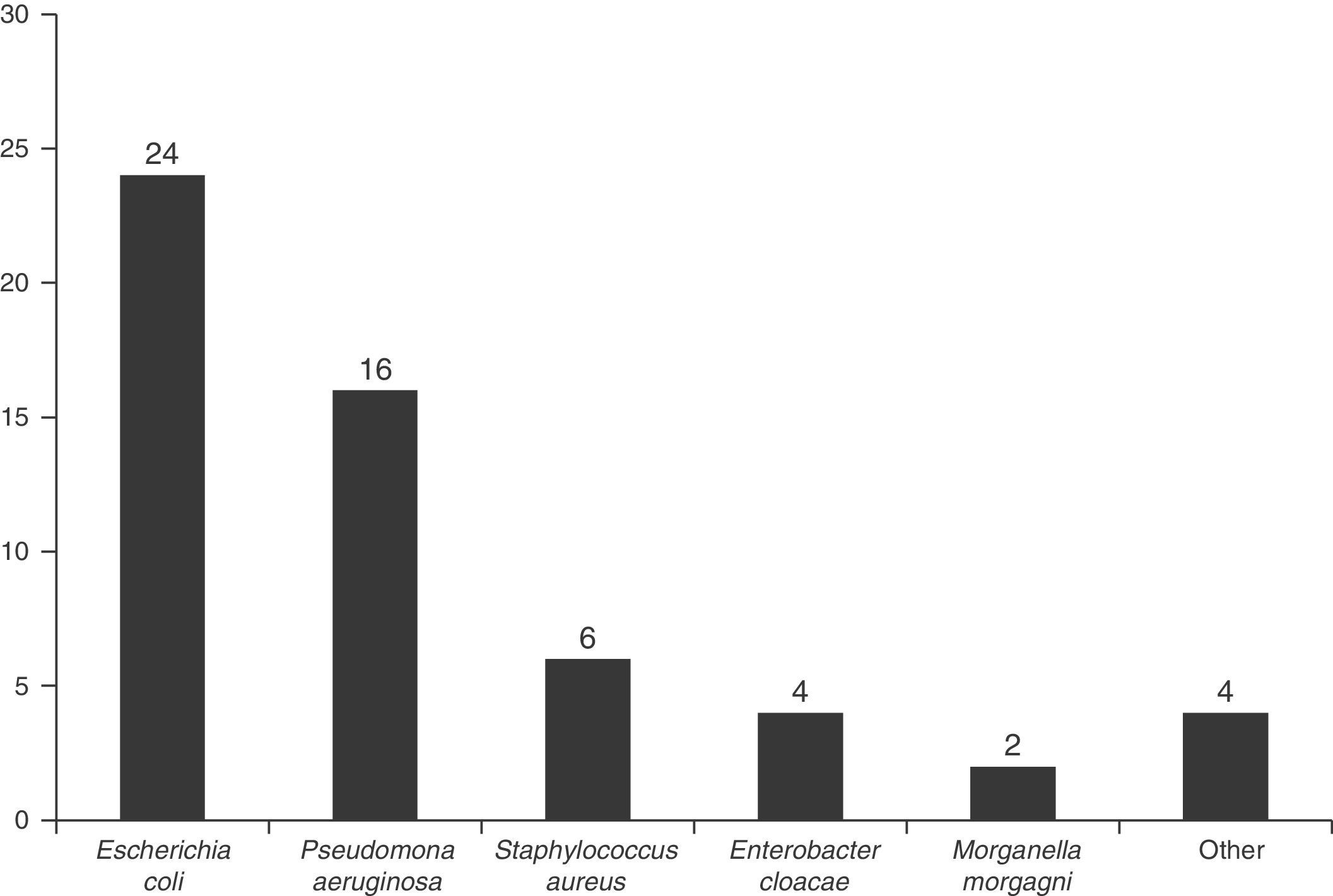

The most common micro-organisms (n: 56) in the surgical wounds were Escherichia coli (43%), and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (29%) (Fig. 1), and 11.6% of the patients with a surgical site infection had polymicrobial infections.

The comorbid risk factors were: diabetes mellitus (2.6%), obesity (2.6%), concomitant neoplasm (1.9%), renal failure (1.5%), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (0.8%) and cirrhosis (0.4%).

The overall incidence of surgical site infection during follow-up was 4.6% (43 infected patients), with an incidence of 4.9% in open surgery, and 2.6% in laparoscopy. The type of overall infection according to depth was 3.5% superficial incisional infection, 0.5% deep incisional infection and 0.5% organ/space infection.

The incidence of surgical site infection in patients who did not receive prophylaxis was 5.2%, and 4.4% in those who did. We found no association between the administration or otherwise of prophylaxis and the onset of surgical site infection (relative risk: 0.66; 95% CI: 0.25–1.57) (p>0.05).

The incidence of surgical site infection in patients with adequate prophylaxis was 4.2% and 5.4% in those for whom it was inadequate. We found no association between the inadequacy of antibiotic prophylaxis and the incidence of surgical site infection (relative risk: 0.50; 95% CI: 0.1–1.9) (p>0.05).

DiscussionThe incidence of surgical site infection is a quality standard in health care.13,14 All types of surgical intervention carry an increased risk of infection, which can manifest locally in the surgical site or remotely. While the former are real surgical site infections, the latter may or may not be directly associated with the intervention, and cannot be termed surgical infections, in the strictest sense.4,15

The prophylactic administration of antibiotics is a means of proven efficacy to prevent and reduce the frequency of surgical site infections,2,7–9 and some studies report a reduced incidence of surgical site infection of up to 56%.16

Our study evaluated the percentage of antibiotic prophylaxis administration in patients who had undergone appendicectomy and the extent of adherence to our hospital's antibiotic prophylaxis protocol. Seventy-one point three percent of the patients received prophylactic treatment. Since appendicectomy is emergency surgery, the degree of compliance was less than that observed in other elective procedures.17,18 However, this percentage was greater than in the literature we consulted on this surgical procedure.19–21 It was not possible to confirm that prophylaxis had been administered to 28.7% of the patients because there was no record in their clinical histories.

Amongst the patients who had received antibiotic prophylaxis, the overall percentage of compliance was 86.1%. This percentage is similar or above that of both the Spanish18,24 and the international22,23 published studies we consulted. The individual criteria studied (choice of antibiotic administered, route, administration within an hour prior to incision, dose, and duration of prophylaxis) showed differing extents of compliance with the protocol, the start time of prophylaxis (86.1%) was the criterion with the lowest compliance rate. In other studies that we consulted the duration of prophylaxis recorded the highest percentage of non-compliance.20,25–27

With regard to the choice of antibiotic administered, the compliance rate was 98.2%, which is a very good result with little margin for improvement. Compliance in terms of dose and administration route was around 100%.

Antibiotic prophylaxis was administered by the operating theatre nursing staff, according to the hospital's protocol and supervised by the anaesthetists, the doctors in charge of their administration. Since neither the nurses nor the anaesthetists knew that they were being assessed, it was possible to control the Hawthorne effect in our study.

Our principal objective was to evaluate prophylaxis compliance and its possible association with a greater incidence of surgical site infection. We found no statistically significant relationship between the incidence of infection in patients who did not receive antibiotic prophylaxis or the patients for whom it was inadequate. In the case where prophylaxis was not given, the most likely explanation could be a failure to record it rather than not having administered it. In the case of the patients with inadequate prophylaxis because of the time the antibiotic was administered, it should be borne in mind that appendicectomies are interventions that are decided in emergency departments and there might be a delay in assessing the patient, administering the prophylaxis and performing the surgical procedure.18,26 Even so, the duration of the operation is not long and the half life of the antibiotic would allow a concentration of bactericide in the incision at the time of surgery.

In the case of patients with inadequate prophylaxis due to the choice of antibiotic, the number of cases was too small to draw accurate enough conclusions. However, it is possible that despite not having chosen the antibiotic defined in the protocol, the antibiotic chosen might have been effective against the flora in our hospital and not have affected the incidence of infection.

As in other studies,28 the most frequently isolated micro-organisms in patients with surgical site infections after appendicectomy in our hospital were Escherichia coli (43%) and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (29%).

The information from evaluating prophylaxis and infection rates is used as a preventive measure, which is sent to surgeons as feedback for continuous improvement in the quality of patient care. Actions targeted at preventing infection are always cost-effective and in a context of limited resources should be considered to add value, both from a financial perspective and from one of continuous improvement in patient care and safety.7,29–32

ConclusionsAlthough compliance with antibiotic prophylaxis in appendicectomies was high in our hospital; the number of surgical site infections is a parameter that can still be improved upon. It is important not only to administer antibiotic prophylaxis in line with the defined protocols, but also to assess compliance in order to take the necessary measures to improve this prophylaxis and reduce the incidence of surgical site infection as much as is possible, to which end infection monitoring and control programmes are priorities.

Because appendicectomy is an emergency surgical procedure made it difficult to achieve 100% compliance with the antibiotic prophylaxis protocol, therefore we suggest that mechanisms should be implemented to make it possible for prophylaxis to be made available to all patients, improving compliance with the protocol, in relation to prophylaxis start time essentially.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this study.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work centre on the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

We would like to thank the Instituto de Salud Carlos III for funding this study with project numbers PI11/01272 and PI14/01136.

Projects co-financed with European regional development funds (ERDF).

Please cite this article as: Sánchez-Santana T, del-Moral-Luque JA, Gil-Yonte P, Bañuelos-Andrío L, Durán-Poveda M, Rodríguez-Caravaca G. Efecto de la adecuación a protocolo de la profilaxis antibiótica en la incidencia de infección quirúrgica en apendicectomías. Estudio de cohortes prospectivo. Cir Cir. 2017;85:208–213.