Diverticular disease is common in industrialised countries. Computed tomography has been used as the preferred diagnostic method; although different scales haves been described to classify the disease, none of them encompass total disease aspects and behaviour.

ObjectiveTo analyse the patients with acute diverticulitis confirmed by computed tomography at the ABC Medical Centre Campus Observatorio from January 1, 2010 to December 31, 2012, in whom pericolic free air in the form of bubbles was identified by computed tomography and if this finding can be considered as a prognostic factor for the disease.

MethodsA series of 124 patients was analysed who had acute diverticulitis confirmed by computed tomography, in order to identify the presence of pericolic bubbles.

ResultsOf the 124 patients, 29 presented with pericolic bubbles detected by computed tomography; of these, 62.1% had localised peritoneal signs at the time of the initial assessment, (p<0.001); leukocytosis (13.33 vs. 11.16, p<0.001) and band count (0.97 vs. 0.48, p<0.001) was higher in this group. Patients with pericolonic bubbles had a longer hospital stay (5.5 days vs. 4.3 days, p<0.001) and started and tolerated liquids later (4.24 days vs. 3.02 days, p<0.001) than the group of patients without this finding.

ConclusionsThe presence of pericolic bubbles in patients with acute diverticulitis can be related to a more aggressive course of the disease.

La enfermedad diverticular es característica de los países industrializados. La tomografía computada se prefiere como método diagnóstico, y aunque se han descrito diferentes escalas para clasificarla, ninguna de ellas engloba el comportamiento completo de la enfermedad.

ObjetivoAnalizar los pacientes con diagnóstico de diverticulitis aguda comprobada por tomografía computada del Centro Médico ABC Campus Observatorio en el periodo comprendido entre el 1 de enero de 2010 al 31 de diciembre de 2012, en quienes como hallazgo tomográfico se identificaron burbujas de aire libre pericólico, y analizar si este hallazgo puede ser considerado como un factor pronóstico de la enfermedad.

MétodosSe analizó el comportamiento clínico de 124 pacientes con presencia de burbujas de aire libre pericólico en la tomografía computada con diagnóstico de diverticulitis aguda.

ResultadosDe los 124 pacientes, 29 presentaron burbujas de aire libre pericólico en la TC; de estos, el 62.1% tenían datos de irritación peritoneal al momento de la valoración inicial (p<0.001); además, presentaban mayor leucocitosis al momento de la valoración inicial (13.33 vs 11.16, p<0.001) y mayor bandemia (0.97 vs 0.48, p<0.001). Así mismo, se identificó una mayor estancia intrahospitalaria (5.5días vs 4.3días, p<0.001) y un mayor tiempo de inicio y tolerancia a la vía oral (4.24días vs 3.02días, p<0.001) en comparación con los pacientes que carecían de este hallazgo tomográfico.

ConclusionesLa presencia de burbujas de aire libre pericólico en pacientes con diverticulitis aguda puede ser relacionada con un curso más agresivo de la enfermedad.

Diverticular disease has an estimated prevalence of between 20% and 60% of the general population. Its incidence increases with age, it is considered a characteristic disease of industrialised countries,1 and is directly associated with low fibre intake. In western countries, colonic diverticulosis is a rare condition in people aged under 40 and affects approximately between 5% and 10% of people in the fifth decade of life, 30% in the sixth decade, and around 60% of patients aged 80. There is no predominance as to gender.2,3

The great majority of patients with colonic diverticulosis remain asymptomatic throughout their lives. Only 20% of these patients develop the most common complication, known as acute diverticulitis (AD). Only 1% will require surgical treatment in any of its forms. An increased prevalence of 16% of patients requiring medical or surgical treatment has been recorded in the past 20 years, with an increase in associated morbidity.4

Gastrointestinal perforation associated with AD is a complication of diverticular disease which constitutes around 75% of the diverticular emergencies that require surgical treatment. It has an associated morbidity of approximately 40–44% and mortality of 4.4–23.7%.5,6

While uncomplicated cases of AD are best treated conservatively with hydration, intestinal rest, analgesia and antibiotic therapy, complicated AD requires drastic measures and more aggressive management. The optimal treatment strategies are currently based on the severity of the disease according to various staging systems such as those of Minnesota, Hinchey and Hinchey as modified by Wasvary et al.7,8 Antibiotics are the conservative treatment of choice for Hinchey 1 diverticulitis, and drainage of the abscess plus antibiotics for Hinchey 2. When these AD events are associated with gastrointestinal perforation with diffuse purulent or faecal peritonitis (Hinchey stages 3 and 4 respectively) treatment is surgical. Unfortunately, the Hinchey staging system and its modified version are based on surgical findings. However, tomographic correlation with Hinchey staging has proved extremely useful in preoperative assessment.9,10 It is important to stress that none of the abovementioned scales mention the presence of free air inside the cavity in any of their forms, either as a localised or as a distant pneumoperitoneum, even though this is a finding that has long been thought an indicator for surgery. These staging systems only mention inflammatory changes in the pericolic fat and the presence of an abscess or fluid (signs of purulent or faecal peritonitis) as relevant.

Traditionally, sigmoidectomy with terminal colostomy (Hartmann's procedure) or sigmoidectomy with primary anastomosis have been the procedures of choice for Hinchey 3 and 4 diverticulitis. Patients with primary anastomoses have been shown to have lower mortality and a shorter hospital stay (HS).11,12

Some less invasive proposals, such as laparoscopic lavage and drainage followed by sigmoidectomy or laparoscopic colectomy in a second operation had proved valuable tools,13 until recently when the poor outcomes of this type of management were demonstrated.14

Routine CT is a valuable tool for assessing diverticular disease. Despite computed tomography's high specificity for Hinchey 3 and 4 (95% and 91%, respectively), its sensitivity for Hinchey 3 is low (42%), which means that a significant number of patients are classed as stage 1 or 2.15 Together with this, the real significance of extra-intestinal free air in the abdominal cavity of patients with AD has not been determined, and there is still great uncertainty as to its value for decision making.16 This finding used to be considered an indicator for surgery and was taken as a sign of a progressing diffuse peritonitis.17

Several current studies have demonstrated that free air in the abdominal cavity of patients with AD is not a determining factor for surgery. The decision to operate should be based on clinical and biochemical rather than radiological findings. Conservative treatment is a viable option in managing patients with free air in the abdominal cavity, providing they are strictly monitored, and the therapeutic approach will have to be changed if there are any signs of clinical deterioration.18

However, some patients with AD only present bubbles of pericolic air on CT. We know that this does not constitute an indicator as to which therapeutic action to choose, and there remains uncertainty as to whether this tomographic finding bears any relation to the prognosis or outcome of the disease, which might be good or poor requiring more aggressive treatment. A few articles in the medical literature refer to this finding as the presence of a localised pneumoperitoneum, but they do not identify its relationship with the clinical picture, prognosis or the relevance of such a finding.

ObjectiveTo study patients with a diagnosis of AD confirmed by CT in the ABC Medical Centre Campus Observatorio from January 1, 2010 to December 31, 2012, in whom pericolic free air in the form of bubbles was identified by computed tomography and if this finding can be considered a prognostic factor for the disease.

Material and methodsAn observational, analytical, longitudinal and retrospective study.

A cohort was studied of all the patients hospitalised in the ABC Medical Centre Campus Observatorio from 1 January 2010 to 31 December 2012 with a diagnosis of AD confirmed by CAT.

The inclusion criteria were: patients of both genders with a diagnosis of AD confirmed by CT and admitted to the ABC Medical Centre Campus Observatorio from 1 January 2010 to 31 December 2012, with complete clinical records.

Cases of AD within the study period who had not been assessed using CT or who did not have a complete clinical record or the required study variables were excluded.

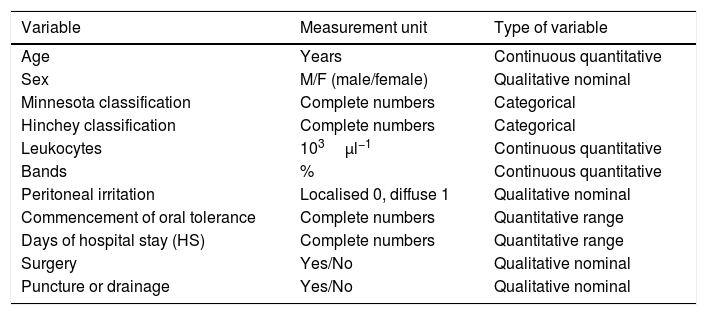

Descriptive statistics were calculated as mean±standard deviation for quantitative variables, frequencies and percentages for qualitative variables. Pearson's correlation coefficient was used to assess the relationship between quantitative variables. Contingency tables were used to record significant differences between categorical variables with the Chi-square test. The ANOVA test was used to detect significant differences between the quantitative variables grouped according to the CT findings. All the probability data were two-tailed tests, and values below 0.05 were considered statistically significant. All the analyses were performed using SPSS for Windows (SPSS, Chicago, IL, U.S.A.). Table 1 shows the variables measured.

Variables.

| Variable | Measurement unit | Type of variable |

|---|---|---|

| Age | Years | Continuous quantitative |

| Sex | M/F (male/female) | Qualitative nominal |

| Minnesota classification | Complete numbers | Categorical |

| Hinchey classification | Complete numbers | Categorical |

| Leukocytes | 103μl−1 | Continuous quantitative |

| Bands | % | Continuous quantitative |

| Peritoneal irritation | Localised 0, diffuse 1 | Qualitative nominal |

| Commencement of oral tolerance | Complete numbers | Quantitative range |

| Days of hospital stay (HS) | Complete numbers | Quantitative range |

| Surgery | Yes/No | Qualitative nominal |

| Puncture or drainage | Yes/No | Qualitative nominal |

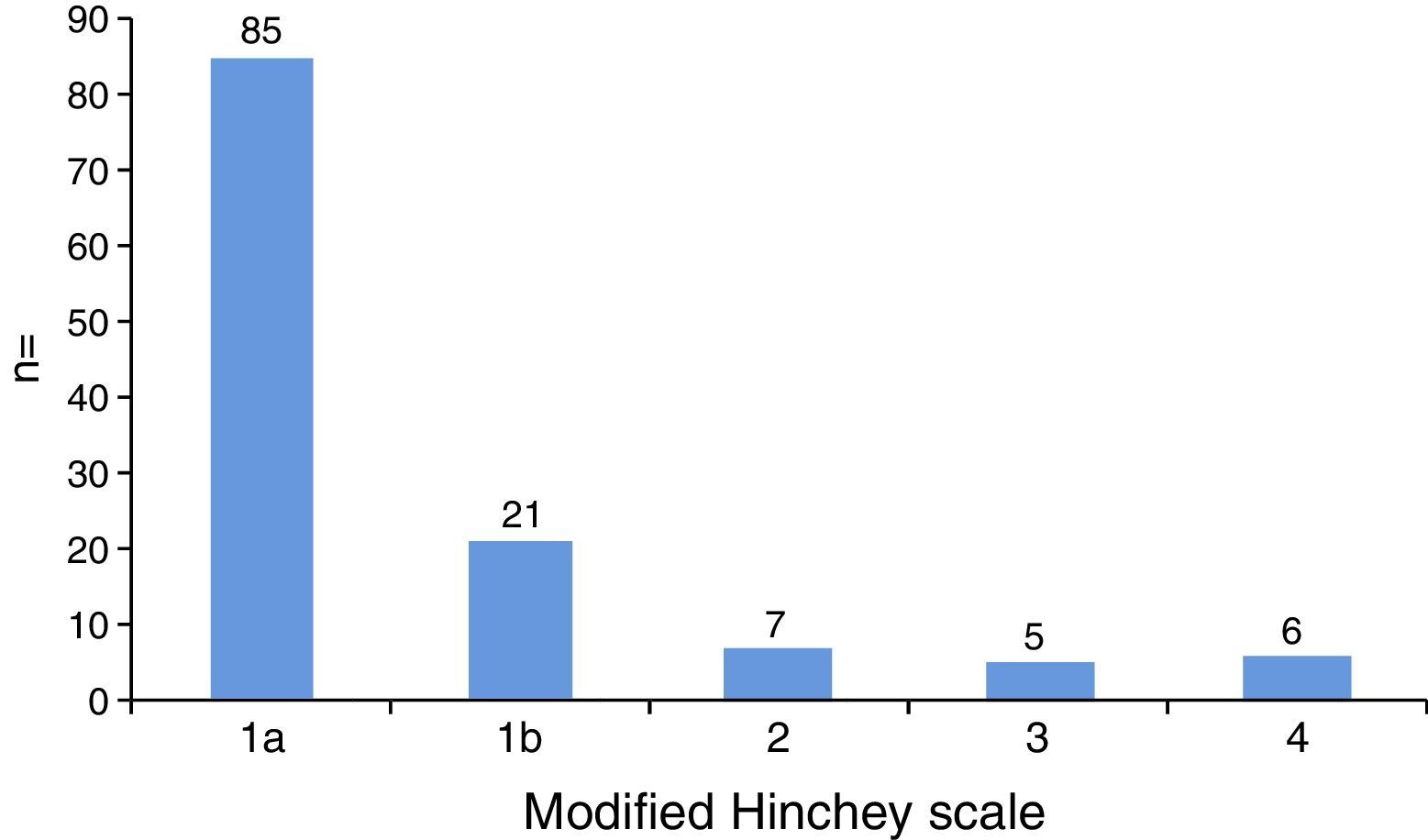

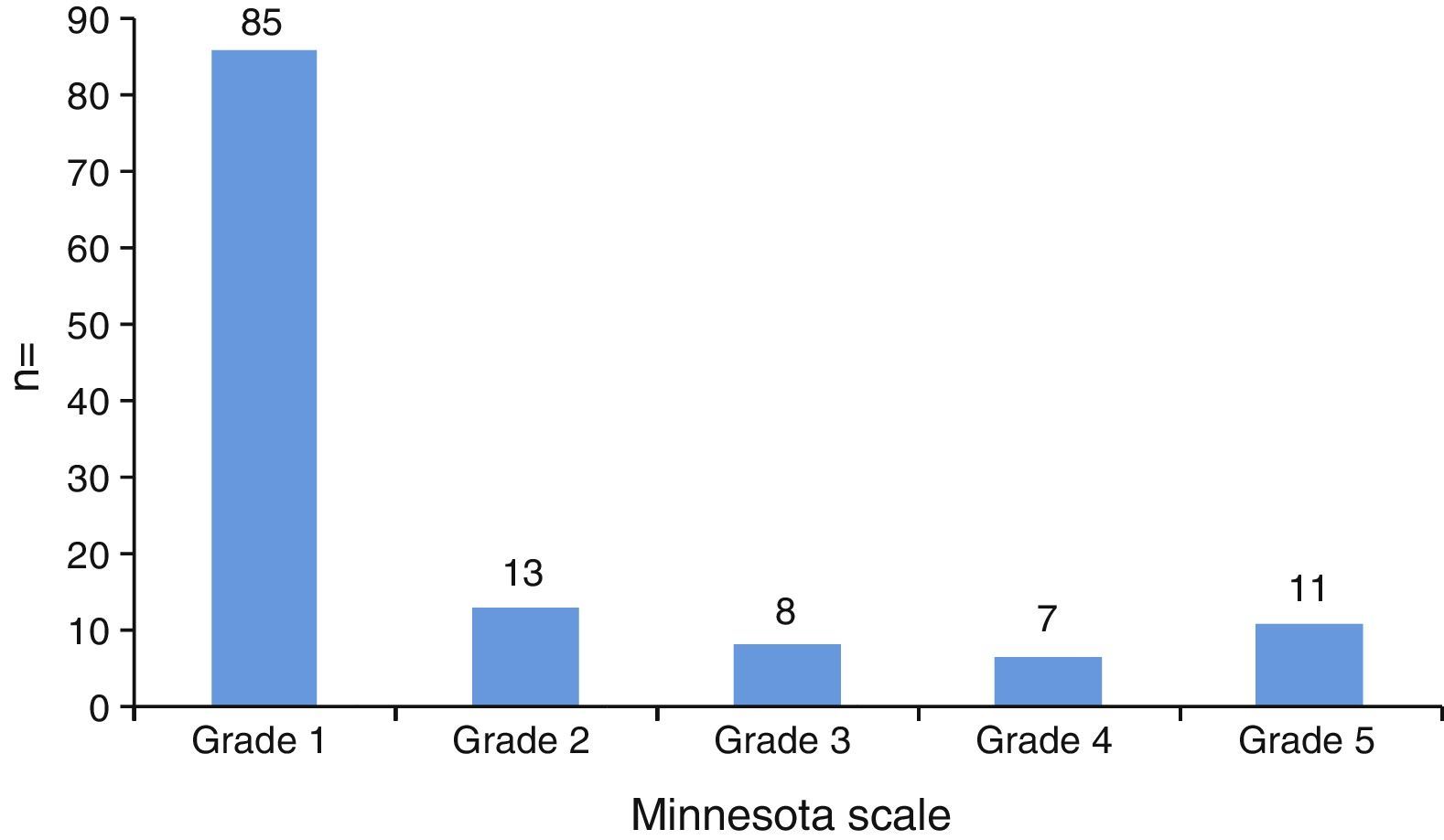

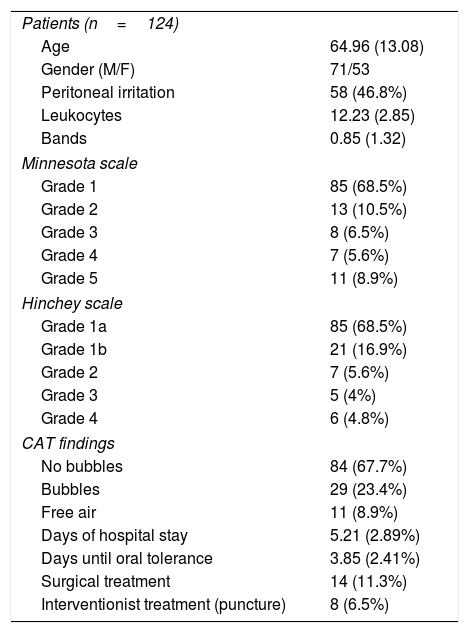

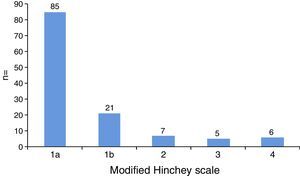

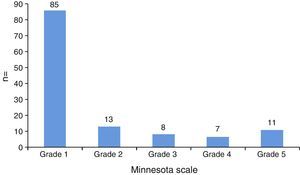

One hundred and twenty-four patients were studied — 71 males (57.2%) and 53 females (42.8%) — with a mean age of 64.9 years (SD: 13.08). The CT findings and the modified Hinchey and Minnesota scales were used to categorise the severity of the disease. It was found that according to both classifications 86 (68.5%) of the patients studied were staged as uncomplicated AD (Minnesota 1, modified Hinchey 1a) (Figs. 1 and 2) (in Fig. 1 the findings of the surgical procedure reported in the clinical history record were used to establish scales 3 and 4).

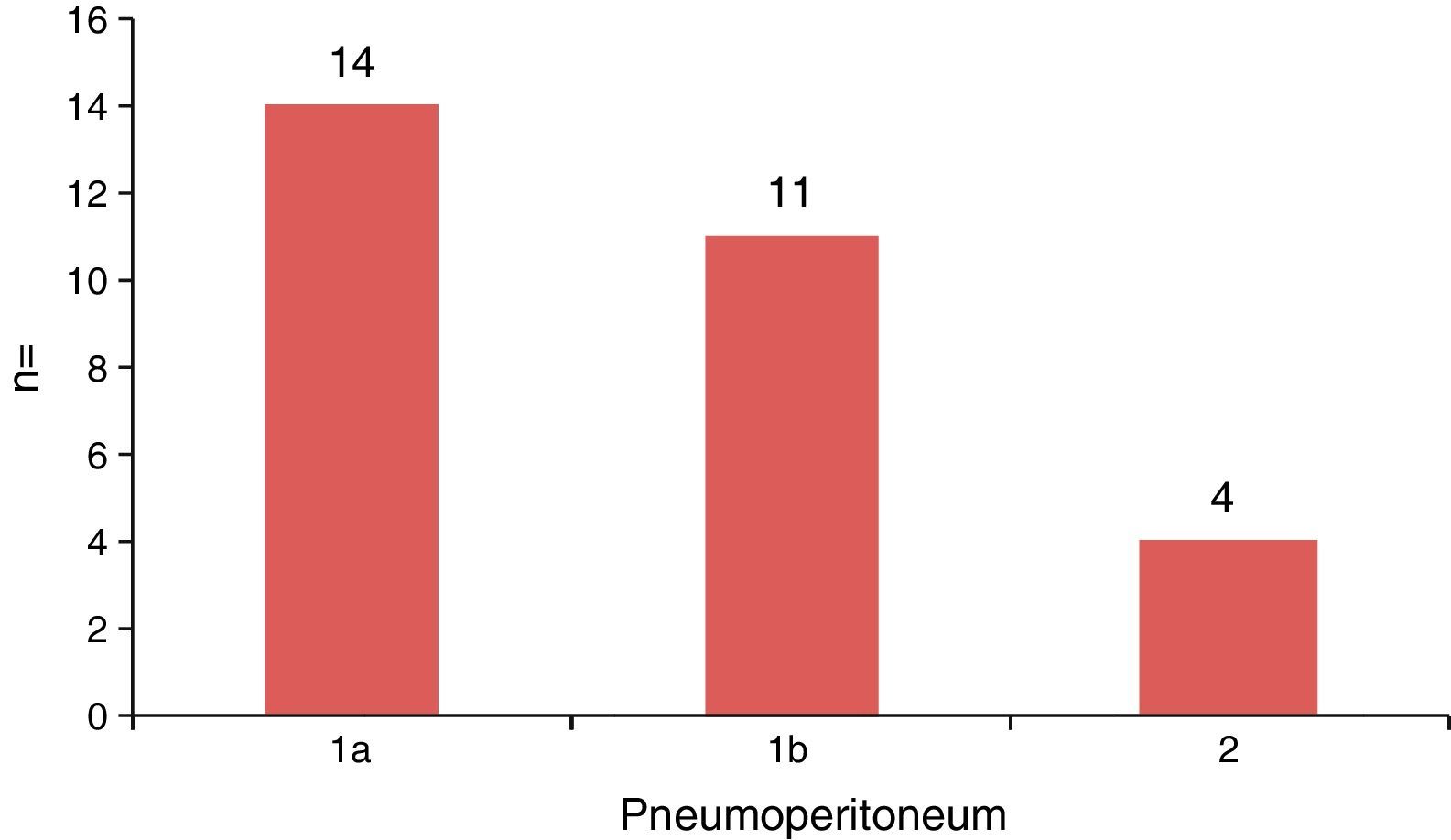

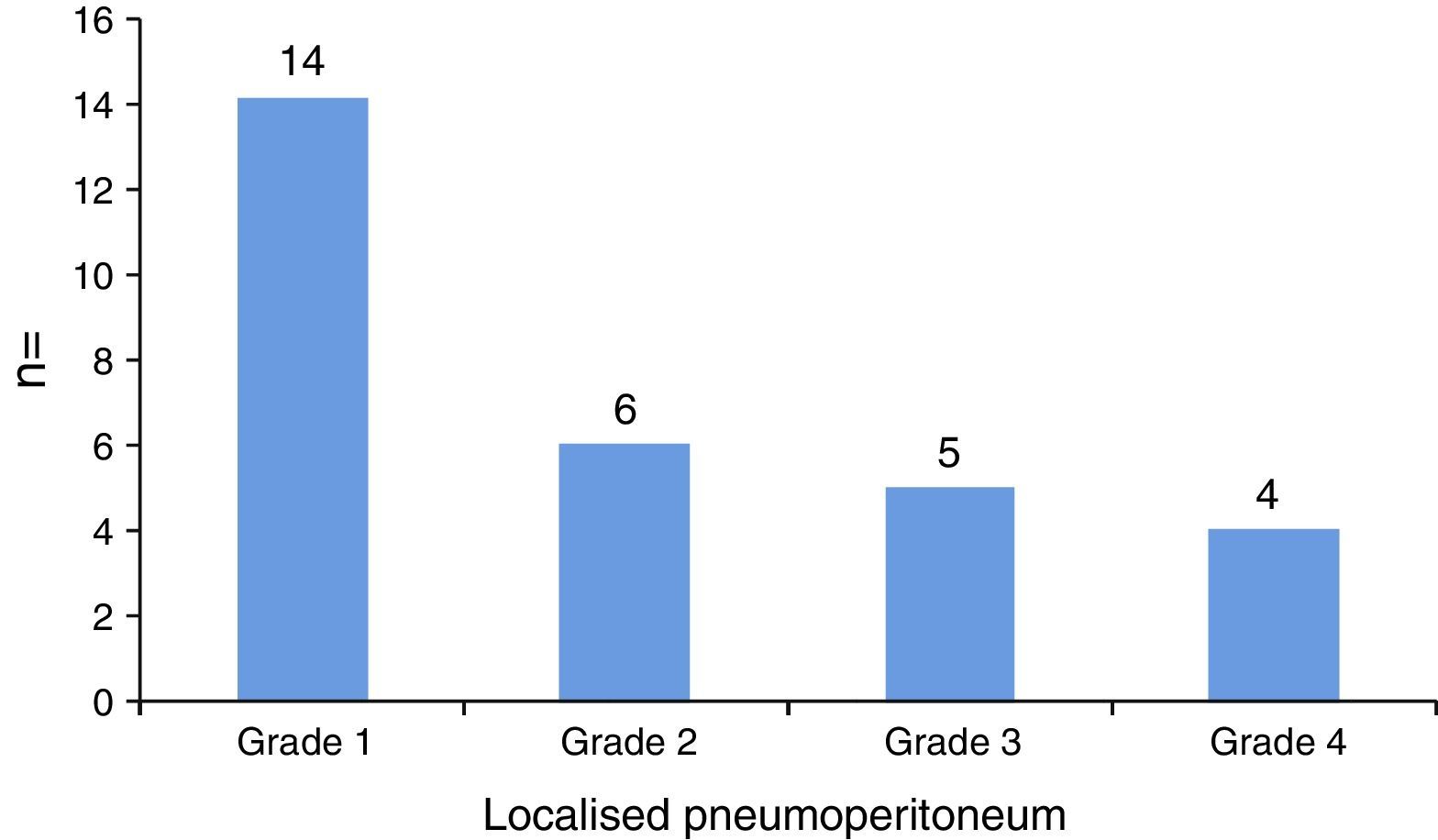

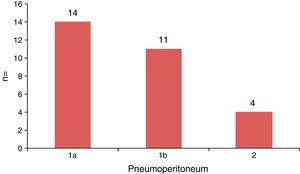

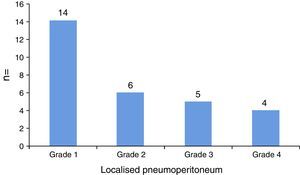

The CT findings of the 124 patients showed that 29 (23.4%) had bubbles of pericolic air, with no presence of subdiaphragmatic free air. These patients are classified according to the modified Hinchey and Minnesota scales in Figs. 3 and 4, respectively. Subdiaphragmatic free air was found in 11 patients (8.9%).

The average HS was 5.2 (SD: 2.8) days, and the mean time to starting oral intake of liquids was 3.8 (SD: 2.4) days.

Only 14 (11.3%) of all the patients studied required some form of surgical treatment, the same for the 11 patients staged as modified Hinchey 3, 4 and Minnesota 5, in line with the 11 patients with the CT finding of subdiaphragmatic free air. The 3 remaining patients who underwent surgical treatment had CT findings of bubbles of pericolic free air and had been staged as modified Hinchey 3 and Minnesota 4, comprising 2.4% of the total sample, and 10.3% of the patients with localised pneumoperitoneum; of these 3 patients, 2 showed major clinical deterioration within the first 24h of their hospital stay (increased heart rate, temperature rise to 38.7°C). Only 8 (6.5) of the subjects of the study required interventionist treatment (puncture and drainage of abscess) to resolve their symptoms, 7 of whom had an abscess larger than 5cm in diameter. The demographic characteristics of the group studied are summarised in Table 2.

Characteristics of the patients included in the study.

| Patients (n=124) | |

| Age | 64.96 (13.08) |

| Gender (M/F) | 71/53 |

| Peritoneal irritation | 58 (46.8%) |

| Leukocytes | 12.23 (2.85) |

| Bands | 0.85 (1.32) |

| Minnesota scale | |

| Grade 1 | 85 (68.5%) |

| Grade 2 | 13 (10.5%) |

| Grade 3 | 8 (6.5%) |

| Grade 4 | 7 (5.6%) |

| Grade 5 | 11 (8.9%) |

| Hinchey scale | |

| Grade 1a | 85 (68.5%) |

| Grade 1b | 21 (16.9%) |

| Grade 2 | 7 (5.6%) |

| Grade 3 | 5 (4%) |

| Grade 4 | 6 (4.8%) |

| CAT findings | |

| No bubbles | 84 (67.7%) |

| Bubbles | 29 (23.4%) |

| Free air | 11 (8.9%) |

| Days of hospital stay | 5.21 (2.89%) |

| Days until oral tolerance | 3.85 (2.41%) |

| Surgical treatment | 14 (11.3%) |

| Interventionist treatment (puncture) | 8 (6.5%) |

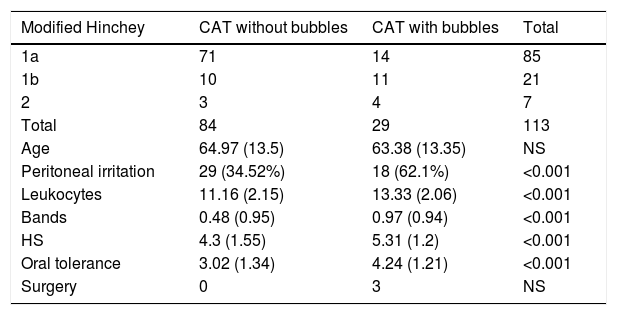

The subgroup of 29 (23.4%) patients who were found to have pericolic free air bubbles was analysed, and 62.1% (n=18) were found to have signs of peritoneal irritation on initial assessment compared to 34.5% (n=29) of the patients with no tomographic finding of bubbles of pericolic free air with a statistical value of p<0.001. Similarly the patients with pericolic free air bubbles found on CT had a higher leucocyte count at the time of initial assessment (13.33 vs. 11.16, p<0.001) and higher band count (0.97 vs. 0.48, p<0.001) compared to the patients without this finding.

The relationship was assessed between the presence of bubbles of pericolic free air and the days of HS until commencement of oral fluid intake with adequate tolerance and discharge from hospital, and it was found that patients with this finding had an average 1.22 days’ delay in tolerating oral intake and 1.01 days longer overall HS compared to patients with no bubbles of pericolic free air.

The findings from analysis of the subgroup of 29 patients with bubbles of pericolic free air compared to the rest of our population are summarised in Table 3.

Characteristics of the patients and their correlation with the modified Hinchey scale. The patients with bubbles of free air had more days of hospital stay (HS) and more days until commencement of oral intake.

| Modified Hinchey | CAT without bubbles | CAT with bubbles | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1a | 71 | 14 | 85 |

| 1b | 10 | 11 | 21 |

| 2 | 3 | 4 | 7 |

| Total | 84 | 29 | 113 |

| Age | 64.97 (13.5) | 63.38 (13.35) | NS |

| Peritoneal irritation | 29 (34.52%) | 18 (62.1%) | <0.001 |

| Leukocytes | 11.16 (2.15) | 13.33 (2.06) | <0.001 |

| Bands | 0.48 (0.95) | 0.97 (0.94) | <0.001 |

| HS | 4.3 (1.55) | 5.31 (1.2) | <0.001 |

| Oral tolerance | 3.02 (1.34) | 4.24 (1.21) | <0.001 |

| Surgery | 0 | 3 | NS |

NS: p not significant.

Only classifications 1a, 1b and 2 are covered in this Table, since the initial management was not surgical.

Finally, a directly proportional correlation was found between the leucocyte count and the days of HS (r=0.519, p=<0.001) with the days of HS until commencement of oral fluid intake (r=0.977, p<0.001), in the patients with bubbles of free air.

DiscussionIn recent years, studies have been undertaken seeking to identify factors to guide surgeons as to the course of the disease and to create therapeutic guidelines to reduce morbidity and mortality rates in complicated diverticulitis cases.

As has already been established, the presence of free air inside the abdominal cavity in patients with AD is not an indicator for surgery, and this has helped make management less aggressive, either using interventionist radiology or, if surgical management is required, by using a minimally invasive approach leaving open surgery as a final resort.19,20

The need for surgical treatment, reported in the literature at 1%, was 11.2% in our population, with a total of 11 cases of AD classified as Hinchey 4, who in turn, as a CT finding, had pericolic, subdiaphragmatic free air inside their abdominal cavity, and 3 cases of modified Hinchey 3 AD with the presence of bubbles of pericolic free air. Recent data reported in the literature by Costi et al.,21 suggest that up to 22.2% of patients with subdiaphragmatic free air or free air distant from the site of inflammation could be successfully managed conservatively. The high incidence of cases of complicated AD that required surgical treatment in this study might be due to the small sample size and not reflect a real increase in these cases; this is in keeping with what has already been described. The preference of the surgeon and population type might have contributed to these results, the ABC Medical Centre being a private care institution.

The surgeons’ therapeutic behaviour should be guided by the patient's haemodynamic stability, inflammatory response markers and clinical progress, using CT findings as an aid to diagnosis and to stage the disease, not as a guide to treatment.

Relevant information with regard to the prognostic factors of the disease, that coincides with the findings of Costi et al.,21 is that leucocyte levels relate to the likelihood of successful conservative management. Their study reports that leukocytosis >20,000mm−3 in patients with AD is associated with the failure of conservative treatment; in our study we found a directly proportional correlation between leucocyte counts and days of HS (r=0.519, p=<0.001), and the days of HS before commencement and tolerance of oral fluid intake (r=0.977, p<0.001). Although we analysed different variables, both sets of data coincide in that the higher the leukocytosis, the more aggressive the course of the disease, which will probably require prolonged or invasive management.

When we refer to the disease's prognostic factors, the presence of pericolic free air in AD has not been assessed previously. The current huge advances in imaging techniques have enabled variables to be studied that hitherto were impossible to identify. In the population studied of 124 patients, 29 (23.4%) had a CT finding of the presence of bubbles of pericolic free air, this finding was previously not considered relevant to the outcomes or treatment of AD patients. However, in this study it is striking that the results indicate that this CT finding might bear a close relationship with the progress of the disease and might suggest a more aggressive course. On comparing the patients with pericolic free air in the abdominal cavity to those without, it was found that the patients with this finding had a longer HS and delayed effective commencement of oral intake (4.3 days HS vs. 5.51 days, p<0.001) (tolerating oral fluid intake at 3.02 days vs. 4.24 days, p<0.001). Likewise, the presence of a localised or pericolic pneumoperitoneum was associated with higher leukocytosis (13.33 vs. 11.16, p<0.001) and band count (0.97 vs. 0.48, p<0.001), suggestive of a more severe inflammatory process with more signs of peritoneal irritation (29 vs. 18, p<0.001). The fact that HS and the time to commencement of oral intake with adequate tolerance were prolonged might be explained by the likely relationship between pericolic free air and a more severe inflammatory process which, as a consequence, resulted in a greater problem inside the abdominal cavity and prolonged ileus. At the moment it is not possible to compare these outcomes with the previous literature. From the data obtained it can be inferred that the presence of pericolic free air – a finding that the Hinchey and Minnesota scales do not assess – might be considered a significant factor that indicates a greater inflammatory response and more severe disease.

Forty-eight percent of the patients with localised pneumoperitoneum were classed 1ª and 1, respectively according to the modified Hinchey and the Minnesota scales. This highlights that, despite having been classed as “uncomplicated diverticulitis”, the course of their disease was more aggressive, as can be seen from our results.

On its own, the presence of pericolic free air is not a sign that requires a change in therapeutic approach for AD patients. However, it might guide the surgeon and warn them of the likelihood of a prolonged course of the disease. Research projects that analyse new therapies and prognostic factors for the disease are still required in order to reduce morbidity and mortality.

ConclusionsThe presence of bubbles of pericolic free air in AD patients might be considered a prognostic factor for the disease, being directly associated with a longer HS and late commencement and tolerance of oral fluid intake compared to AD patients without this CT finding. Likewise, these results suggest that the presence of a localised or pericolic pneumoperitoneum is associated with higher leukocytosis and band count, and a greater incidence of peritoneal irritation on initial assessment of the patient.

For the moment, the data obtained suggest that, although the presence of pericolic free air in AD patients does not directly imply a change in therapeutic approach, it might indeed be a prognostic factor of a more severe course of the disease.

Further studies are required to assess this finding of localised pneumoperitoneum to establish with greater certainty how useful it is in the management of AD. We are aware that the limitations of our study were that it was retrospective with a small patient sample.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this study.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: García-Gómez MA, Belmonte-Montes C, Cosme-Reyes C, Aguirre Garcia MP. Valor pronóstico de la presencia de burbujas de aire libre pericólico detectadas por tomografía computada en diverticulitis aguda. Cir Cir. 2017;85:471–477.