Sialorrhoea has a prevalence of between 10% and 58% in patients with cerebral palsy. Amongst the invasive treatments, botulinum toxin-A injections in submandibular and parotid glands and various surgical techniques are worth mentioning. There are no studies in Mexico on the usefulness of surgery to manage sialorrhoea.

ObjectiveTo evaluate the usefulness of submandibular gland resection in improving sialorrhoea in patients with cerebral palsy and with a poor response to botulinum toxin.

Material and methodsExperimental, clinical, self-controlled, prospective trial was conducted to evaluate the grade of sialorrhoea before surgery, and 8, 16 and 24 weeks after. Statistical analysis was performed using a non-parametric repetitive measure assessment, considering a p<0.05 as significant. Complications and changes in salivary composition were evaluated.

ResultsSurgery was performed on 3 patients with severe sialorrhoea, and 2 with profuse sialorrhoea, with mean age of 10.8 years. The frequency and severity of sialorrhoea improved in the 5 patients, with mean of 76.7 and 87.5% improvement, respectively. The best results were seen after 6 months of surgery, with a statistically significant difference between the preoperative stage and 6 months after the procedure (p=0.0039, 95% CI). No significant differences were observed in complications, increase in periodontal disease or cavities, or salivary composition.

ConclusionsSubmandibular gland resection is an effective technique for sialorrhoea control in paediatric patients with cerebral palsy, with a reduction in salivary flow greater than 80%. It has a low chance of producing complications compared to other techniques. It led to an obvious decrease in sialorrhoea without the need to involve other salivary glands in the procedure.

La prevalencia de sialorrea en pacientes con parálisis cerebral es del 10-58%. Puede tratarse con aplicación de toxina botulínica en glándulas salivales o con técnicas quirúrgicas que disminuyen definitivamente la producción salival. En México no existen estudios sobre la utilidad de la cirugía para manejar la sialorrea.

ObjetivoEvaluar la eficacia de la resección de glándulas submandibulares, para disminuir la sialorrea en pacientes pediátricos con parálisis cerebral y con resultados desfavorables con toxina botulínica.

Material y métodosEnsayo clínico experimental, autocontrolado, longitudinal y prospectivo. Se realizó evaluación prequirúrgica del grado de sialorrea y posquirúrgicas a 8, 16 y 24 semanas, con una clasificación validada. Se aplicó una prueba de medidas repetidas no paramétrica, para buscar significación estadística con p<0.05. Se analizan también las complicaciones observadas y los cambios en la composición salival.

ResultadosSe operó a 3 pacientes con sialorrea severa y a 2 con profusa, con edad media de 10.8 años. Los 5 mejoraron en severidad y frecuencia, con disminución promedio del 76.75 y del 87.5%, respectivamente. El mejor resultado se observó a los 6 meses, con diferencia estadísticamente significativa entre el preoperatorio y el postoperatorio (p=0.0039, IC 95%). No se observaron complicaciones importantes, deterioro dental ni cambios importantes en la composición salival.

ConclusionesLa resección de glándulas submandibulares es efectiva para controlar la sialorrea en pacientes pediátricos con parálisis cerebral, con reducción superior al 80%. Tiene una tasa baja de complicaciones, a diferencia de otras técnicas. Generó una disminución suficiente y evidenciable de la sialorrea en reposo, sin necesidad de trabajar con otras glándulas salivales mayores.

Sialorrhoea is defined as the involuntary and passive loss of saliva from the mouth due to an inability to manage oral secretions, and its presence is considered normal until the age of 2 years, when oral motor function becomes more developed. It occasionally continues in children up to age 4, especially when teething, but it is always considered abnormal beyond the age of 4.1

After 6 years of age sialorrhoea frequently presents in people with neuromuscular disorders, including, juvenile cerebral palsy, lateral amyotrophic sclerosis, Parkinson's disease, facial palsy and cerebral vascular event, which result in incoordination during the oral phase of swallowing and an accumulation of saliva in the anterior portion of the mouth, and subsequent drooling.2

Saliva is a complex mixture of macromolecules and electrolytes that is secreted by 3 pairs of major salivary glands (parotid, submandibular and sublingual) and a great number of minor salivary glands, distributed principally through the mucosa in the oral cavity and oropharynx. It has various functions including: lubrication, protection, acid-base buffering, maintenance of dental integrity, antibacterial activity, perception of tastes and digestion.3–9

The set of glands produce approximately 1ml of saliva per gram of gland tissue per minute. This amount increases and decreases as olfactory and gustatory stimuli are generated throughout the day. On average saliva production that has not been stimulated is 0.3ml/min, while stimulated production is 7ml/min, therefore it is possible to calculate that a person produces between 1 and 1.5l of saliva per day (if we consider an average flow of 1ml/min). At rest, 70% of salivary excretion comes from the submandibular gland, along with the parotid gland which produces approximately 25%. This reverses during the process of feeding; the parotid gland produces the most saliva.10,11

Physiological control of salivation is maintained by the autonomic system. Stimulation of the acinar cells by the parasympathetic nervous system creates an increase in the levels of fluid secreted, with more liquid and abundant saliva, while adrenergic stimulation by the sympathetic nervous system, through noradrenaline, generates thicker saliva production with a greater proportion of proteins and macromolecules, amylase in particular.12–14

Cerebral palsy is the most common cause of disability in children, with an incidence in Mexico of 6 per 1000 live births and 12,000 new cases per year.

Over the past 5 years, the National Rehabilitation Institute registered an average of 250 annual admissions of paediatric patients with cerebral palsy. The prevalence of sialorrhoea in children with juvenile cerebral palsy varies. Crysdale15 estimated that 10%–15% present severe sialorrhoea, Tahmassebi and Curzon16 reported an estimated 58% and Sullivan et al.17 estimated 28%. This sign has a major effect on the patient's quality of life and that of their family, due to the strong psychological, medical and financial implications that it causes the patient, their family and the healthcare institution.

There are various types of conservative treatment for severe and profuse sialorrhoea; of these, it is considered that oral motor training should be the initial treatment over at least 6 months. This programme improves closure of the lips, tongue movements and closure of the jaw. Other non-invasive techniques include feedback and behavioural modification strategies with positive or negative reinforcement, which have only produced results in mild cases. Given that saliva is produced to a great extent by parasympathetic stimuli, anticholinergic agents such as atropine, benztropine and scopolamine have been used to diminish its production. They have all been part of therapy trials where no marked efficacy has been demonstrated, and they also cause major adverse effects such as constipation, xerostomia, urinary retention, blurred vision or glaucoma, amongst others.18

Invasive therapeutic alternatives include the application of botulinum toxin into the submandibular or parotid glands and various surgical techniques aimed at definitive reduction of saliva production. Surgery is currently reserved for cases that are refractory to botulinum toxin; however, it is the first choice in several centres.19–21

Botulinum toxin is produced by Clostridium botulinum, an anaerobic bacteria formed from spores, whose natural habitat is soil. This toxin is a simple polypeptide chain which consists of a100-kDa heavy chain, linked via a single disulfide bond to a 50kDa light chain. The light chain is an endopeptidase which contains zinc and has the ability to bind to specific sites of the soluble N-ethylmaleimide sensitive fusion attachment protein receptor (SNARE), which is a synaptic fusion complex essential for vesicle fusion and the subsequent release of acetylcholine to the synaptic cleft. As a result of the toxin's binding to the SNARE protein, the release of acetylcholine is blocked and results in a temporary flaccid paralysis at the neuromuscular junctions or parasympathetic denervation at neuroglandular level.22–24 There are 7 different antigenic types of botulinum toxin, denoted by letters A to G. Each type has an affinity for a different SNARE protein sub-site; for example, type A binds to the transporter protein SNAP-23, whereas type B binds to the transporter protein synaptobrevin also known as vesicle-associated membrane protein (VAMP).25–27

Only botulinum toxin types A and B have been used therapeutically in human beings. The first study to mention the benefits of applying type A botulinum toxin to reduce sialorrhoea in patients with lateral amyotrophic sclerosis appeared in 1997.28 Since then, various studies have tested its usefulness in patients with severe sialorrhoea, of different causes. The disadvantage with the toxin is that its effects are only beneficial short term and require repeat applications every 3–6 months, to maintain control of the condition. Although most of the studies based on ultrasound-guided application of the toxin have demonstrated an acceptable safety profile, there are no long-term studies that establish whether there are possible adverse effects after repeated doses, and children require general anaesthesia each time the procedure is performed.29–34

Surgery is the last step of treatment. In general, surgery should wait until the patient is 6 years old to ensure complete neurological maturity. Surgical treatment is indicated when the sialorrhoea is so severe that conservative measures cannot control it, when it is unlikely that the patient will adhere to conservative treatment due to a motor or serious intellectual deficit and poor family support, or in children over 6 for whom conservative treatment has proved insufficient, in the opinion of their family.19 Given that the submandibular glands are responsible for producing approximately 70% of resting saliva (the parotid glands produce saliva especially during eating), the surgical techniques principally focus on their management. Various surgical techniques have been proposed to treat severe and profuse sialorrhoea. In 1967, Wilkie and Brody35 relocated the parotid ducts towards the tonsillar fossa after tonsillectomy in 123 patients, and performed bilateral excision of the submandibular glands. After a follow-up of 10 years, they reported good control in 90% of their patients, although 43 had major complications, including: wound dehiscence, parotid duct stenosis, poor oral hygiene and increased dental and gum infections. Bilateral relocation of the submandibular ducts towards the tongue base, after the line of the circumvallate papillae, was first described by Laage-Hellman36 in 1969. Crysdale et al.37,38 performed this procedure on 522 patients from 1978. From 1988 they added concomitant resection of the sublingual glands to their procedure, and managed to greatly reduce the development of ranula. Both subgroups showed very good effectiveness in controlling sialorrhoea (75%–85% success rate), no scars are left because an intraoral approach is used. In 1979, Dundas and Peterson39 reported that with bilateral ligature of the parotid ducts together with excision of the submandibular glands they achieved good control in 9 out of 14 cases, although 2 presented xerostomia and 4 increased gum disease. Studies reporting results after fourduct ligation, in general, show less certain outcomes and have more complications.40,41

A meta-analysis was published in 2009, to review the literature between 1963 and 2008, on the surgical management of sialorrhoea in the paediatric patient.20 The meta-analysis looked at the efficacy of the different techniques (tympanic neurectomy, submaxillary gland resection, relocation of Wharton's ducts, resection of sublingual glands, ligation of Wharton's duct, relocation of Stensen's ducts, ligation of Stensen's ducts or any combination of these).

Of 325 articles, 50 met the selection criteria (47 case series, 2 cohort and one prospective study). The combined percentage of successful procedures was 81.6%. Relocation of Wharton's ducts was the most reported procedure (21 studies). Submandibular gland resection and relocation of the parotid conducts presented the highest subjective success rates at 87.8% (8 studies), and the least successful technique was fourduct ligation at 64.1% (4 studies).

Comparing confidence intervals, submandibular gland resection with rerouting of the parotid ducts (n=8 studies; CI 95%: 80.5%–95.1%; p<0.001) was statistically superior to rerouting of Wharton's ducts with sublingual gland resection (estimated subjective success, 71.5%; n=21 studies; CI 95%: 63.6%–79.4%; p<0.001); however, due to the statistical power of these and the variability in the number of studies involving these 2 techniques, it is not possible to establish a definitive selection criterion between either. Submaxillary gland resection with parotid duct ligation was the third technique with the best results in terms of effectiveness. Any of these 3 techniques provide favourable outcomes.

One of the most common concerns in the surgical management of sialorrhoea is that an increase in dental bacterial plaque, dental caries and periodontal disease has been indicated in these patients, due to the major reduction in saliva production and its protective function. This issue is still under debate and the current proposal is that patients that are managed surgically should undergo periodic dental checks, in order to prevent this complication.29

With regard to the complications after the aforementioned surgical techniques, a study performed by Greensmith et al.19 in 2005, the first with follow-up at 5 years, reported that of 67 patients who underwent rerouting of Wharton's ducts with sublingual gland resection, 13 (18%) presented complications, which included minor bleeding in one patient and major bleeding in 3, airway obstruction due to lingual oedema in 2, one submandibular abscess, one partial lesion of the lingual nerve and one aspiration pneumonia. As in the studies of Crysdale et al.37,38 no ranula presented, in contrast to when the sublingual glands were left.

These outcomes were comparable with those of a smaller series performed by Uppal et al.42 and with the problems encountered in the large patient series of Crysdale et al.37,38 In general, these authors consider that, in patients who do not achieve the expected success after surgery, it is possible to ligate a parotid duct with good results, although with an increased prevalence of dental and periodontal disease. Management of sialorrhoea has developed over several years and is currently considered the gold standard for its treatment. However, there have been no studies with the characteristics that we set out here in either the national or international media, based on a review of the literature from 20 years ago to the present date.

ObjectiveGeneralTo evaluate the severity and frequency of sialorrhoea, according to the Thomas Stonell and Greenberg scale,43 before and after submandibular gland resection in paediatric patients with cerebral palsy, with unfavourable results after the application of botulinum toxin type A.

Specific- •

To describe the complications generated by surgical resection of the submandibular glands in paediatric patients with cerebral palsy.

- •

To describe whether glandular resection and reduction of salivation are associated with an increased number of dental caries.

- •

To describe whether there are significant changes in the electrolyte, protein and enzyme components of saliva after submandibular gland resection.

An experimental, self-controlled, longitudinal and prospective clinical trial was undertaken which assessed the outcomes achieved with submandibular gland resection in patients with severe sialorrhoea, who had not responded adequately to the previous application of botulinum toxin type A, in the period between 1 January 2012 and 31 December 2013.

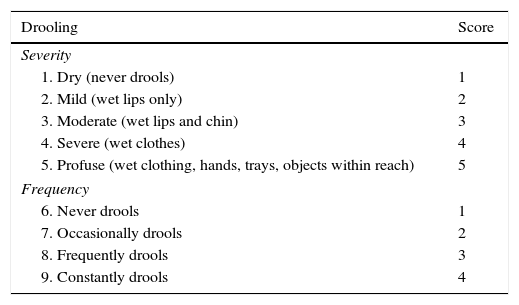

The study included patients from the Paediatric Rehabilitation Department of the Instituto Nacional de Rehabilitación, aged between 6 and 15 years of age, with at least 2 applications of botulinum toxin and minimal response on the scales of frequency and intensity (less than or equal to one grade on the Thomas-Stonell and Greenberg scale) (see Table 1). Patients with blood dyscrasias, concomitant neuromuscular disease, application of toxin before 6 months, lack of authorisation from the legal representative or guardian to undertake the surgical procedure and in whom drugs affecting sialorrhoea were used, were excluded from the study.

Thomas-Stonell and Greenberg drooling severity and frequency scale.

| Drooling | Score |

|---|---|

| Severity | |

| 1. Dry (never drools) | 1 |

| 2. Mild (wet lips only) | 2 |

| 3. Moderate (wet lips and chin) | 3 |

| 4. Severe (wet clothes) | 4 |

| 5. Profuse (wet clothing, hands, trays, objects within reach) | 5 |

| Frequency | |

| 6. Never drools | 1 |

| 7. Occasionally drools | 2 |

| 8. Frequently drools | 3 |

| 9. Constantly drools | 4 |

Taken from: Thomas-Stonell and Greenberg.43

Patients who did not attend the medical consultations before and after the surgical procedure or who died for reasons not associated with the surgical procedure were withdrawn from the study.

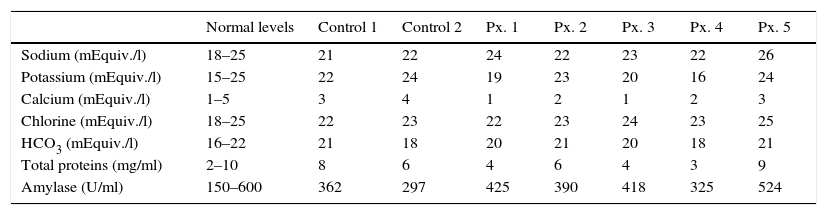

Candidates suitable for surgical management that complied with the criteria mentioned (n=5) were selected and, after allowing a flush-out time of the drug (botulinum toxin type A) of at least 6 months, a presurgical evaluation was made of the grade of sialorrhoea, and postsurgical assessments at 8, 16 and 24 weeks, based on the Thomas-Stonell and Greenberg scale.43 The salivary composition was analysed at 24 weeks after the procedure using basic chemistry studies. In order to make a comparison, the concentrations were measured of various electrolytes, enzymes and proteins in the 5 operated patients, and in 2 randomly selected controls of a group of healthy children of the same age range.

The analysis included: sodium in mEquiv./l, potassium in mEquiv./l, calcium in mEquiv./l, chlorine in mEquiv./l, bicarbonate in mEquiv./l, total proteins in mg/ml and salivary amylase in U/ml. The values of the 2 controls were compared with those known to be normal according to the literature6,14 in order to ensure appropriate sampling and the postsurgical levels at 24 weeks of each patient were then compared with those of the 2 controls.

The measures of central tendency and dispersion were established for the statistical analysis. In order to evaluate the effect of the treatment on severity and frequency according to the Thomas-Stonell and Greenberg,43 a nonparametric repeated measures test was applied (Friedman test with Dunn's test for multiple comparison) taking the presurgical stage of each patient as the baseline status, to compare this status with the effect of the treatment at 4 and 6 months. A variance analysis was undertaken to detect significance in the electrolyte variations of the salivary composition, between the 5 operated cases and the 2 healthy controls. SPSS v19 software was used for the data analysis, taking a p value of <0.05 (CI 95%) as statistically significant.

In terms of ethical considerations, this was a study with minimal risk according to article 17 of Chapter 2 “On the ethical aspects of research on human beings. General aspects” included in the Ruling of the General Health Act in the Area of Health Research. It was approved by the Ethics and Research Committee of the National Rehabilitation Institute.

ResultsFive patients underwent the surgical procedure, 3 of whom presented severe and 2 profuse sialorrhoea at 6 months from the last application of botulinum toxin type A.

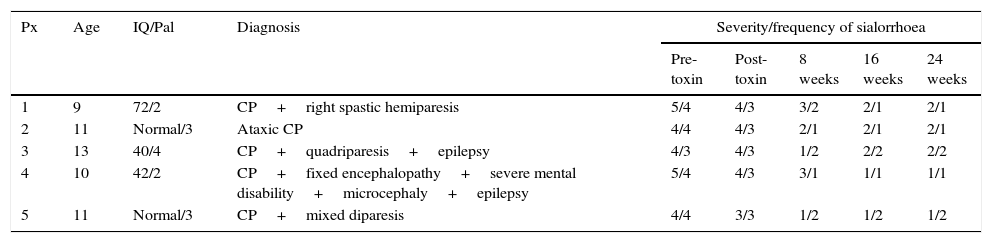

The patients were aged between 9 and 13 years, with a mode of 11 and mean of 10.8 years of age. The baseline diagnoses of these patients were: cerebral palsy with double spastic hemiparesis, ataxic cerebral palsy, cerebral palsy with spastic quadriparesis, mixed disparesis and fixed encephalopathy with severe mental disability, microcephaly and epilepsy. The patients presented an IQ of 42, 47 and 70, 2 patients were of normal IQ and all had a Palisano's gross motor function classification for cerebral palsy score of II or higher. The number of applications of toxin that they had received prior to surgery was 2 per gland in 4 patients; the other patient had 3 applications. The first application was always 20IU per submandibular gland, distributed over 3 different sites, and the second and third application (in one case), 40IU per gland using the same technique. The response to the botulinum toxin was considered poor, considering improvement of one point or less on Thomas-Stonell and Greeberg's43 severity and frequency scale, when the effect lasted under 2 months or when it reduced between the first and second application, even when the dose was doubled (see Table 2).

Patient features and severity of sialorrhoea in baseline status, with the use of botulinum toxin and after submandillary gland resection at 2, 4 and 6 months.

| Px | Age | IQ/Pal | Diagnosis | Severity/frequency of sialorrhoea | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-toxin | Post-toxin | 8 weeks | 16 weeks | 24 weeks | ||||

| 1 | 9 | 72/2 | CP+right spastic hemiparesis | 5/4 | 4/3 | 3/2 | 2/1 | 2/1 |

| 2 | 11 | Normal/3 | Ataxic CP | 4/4 | 4/3 | 2/1 | 2/1 | 2/1 |

| 3 | 13 | 40/4 | CP+quadriparesis+epilepsy | 4/3 | 4/3 | 1/2 | 2/2 | 2/2 |

| 4 | 10 | 42/2 | CP+fixed encephalopathy+severe mental disability+microcephaly+epilepsy | 5/4 | 4/3 | 3/1 | 1/1 | 1/1 |

| 5 | 11 | Normal/3 | CP+mixed diparesis | 4/4 | 3/3 | 1/2 | 1/2 | 1/2 |

IQ: intelligence quotient; Dx: diagnosis; Pal: Palisano scale; CP: cerebral palsy; Px: patient.

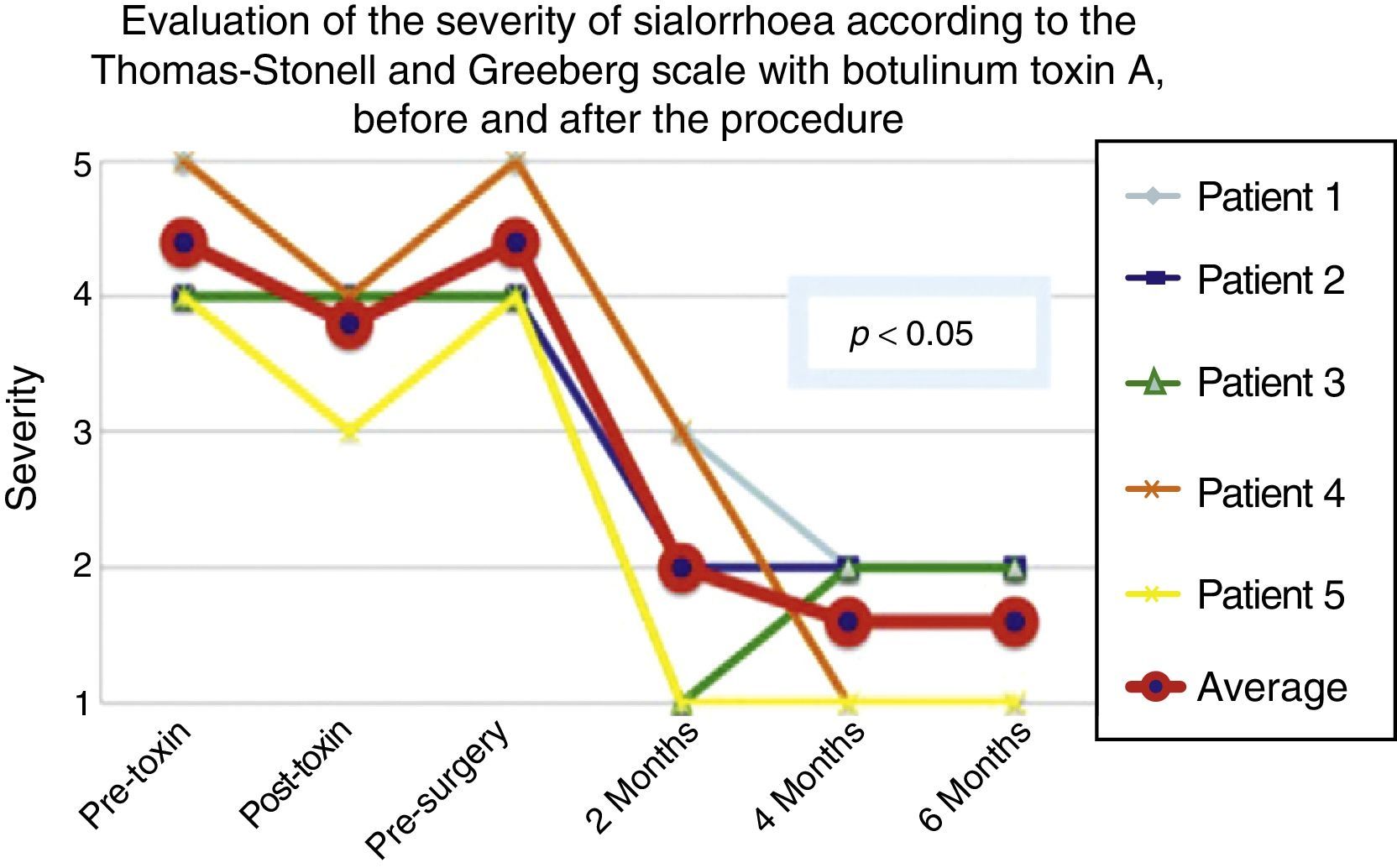

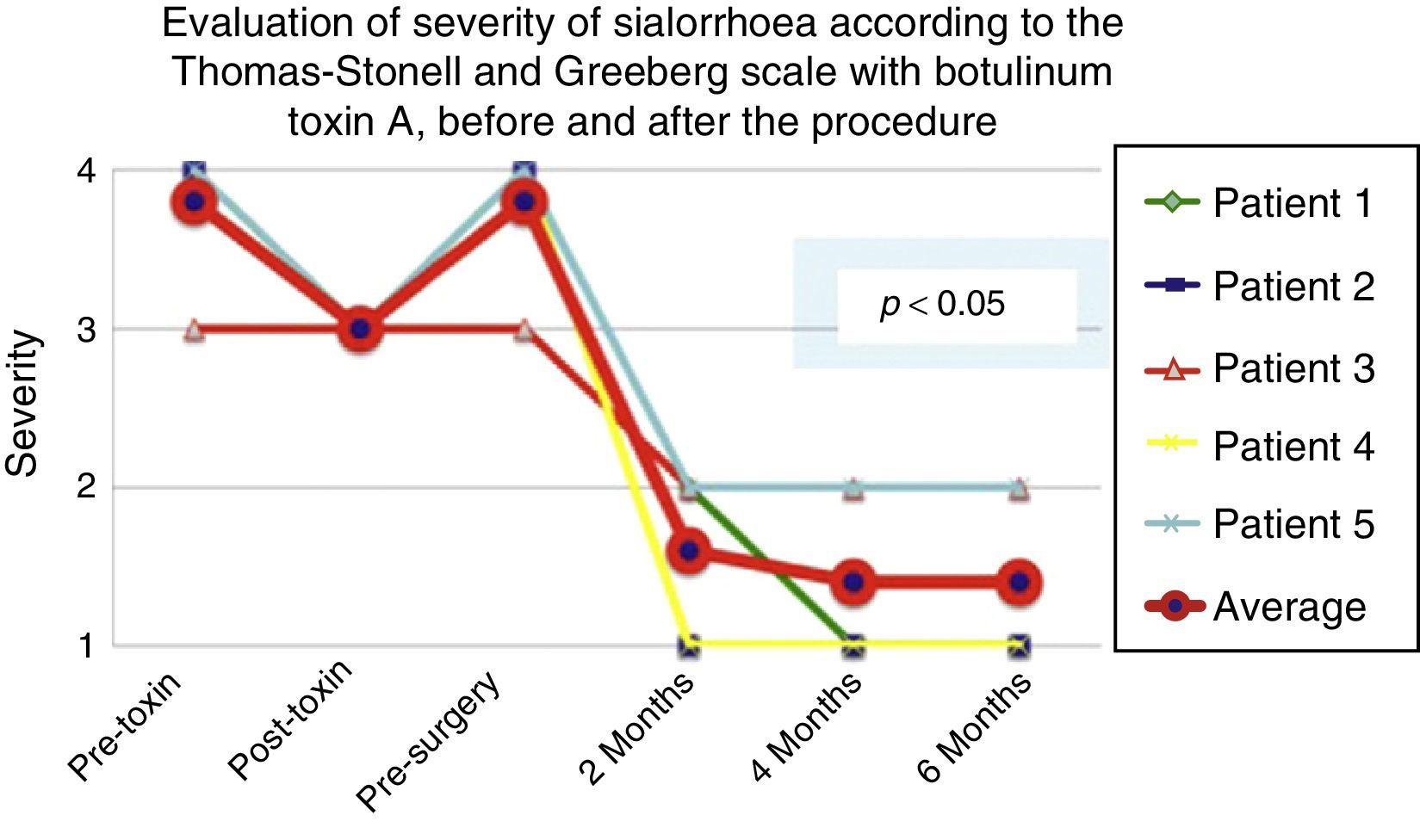

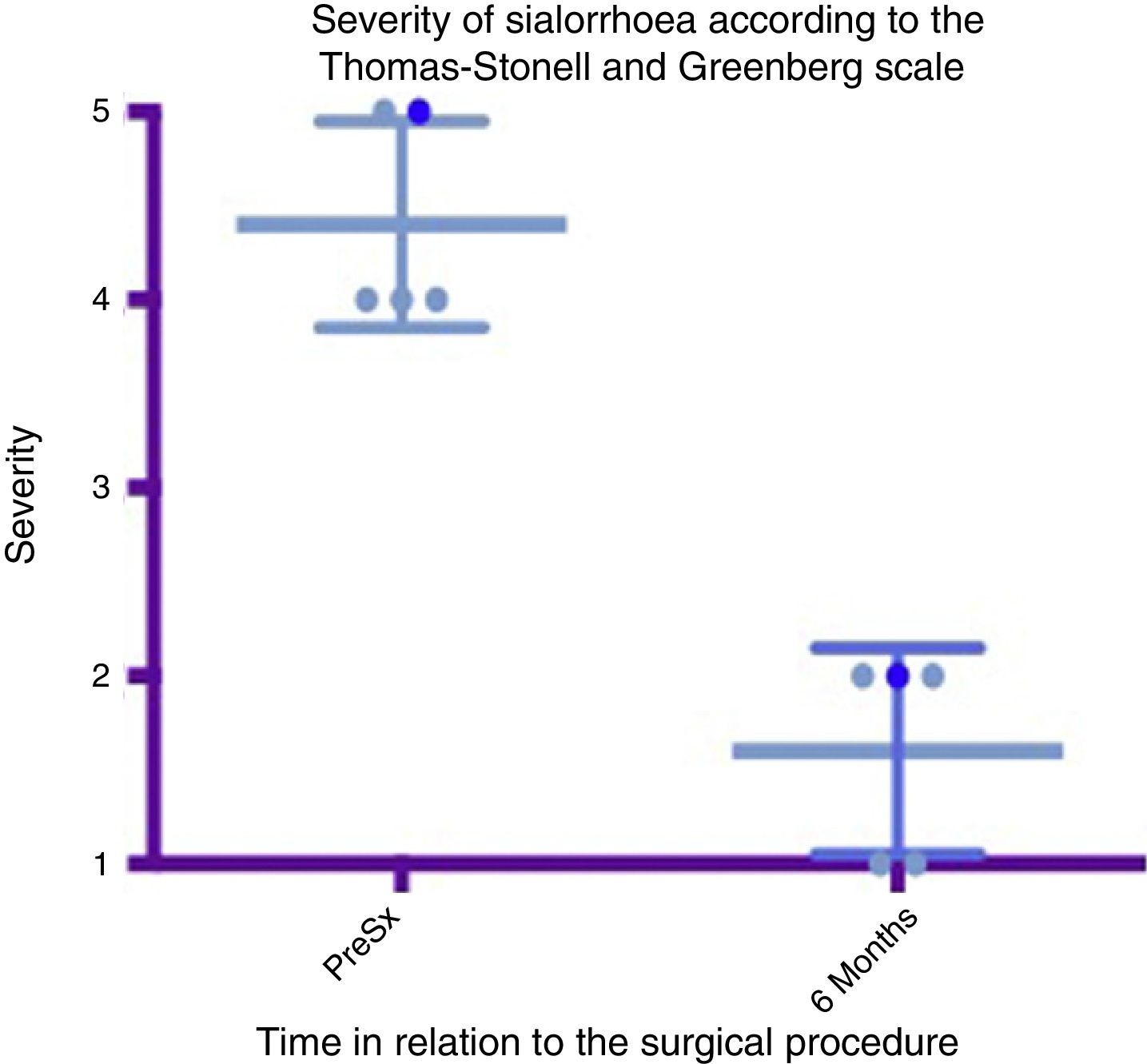

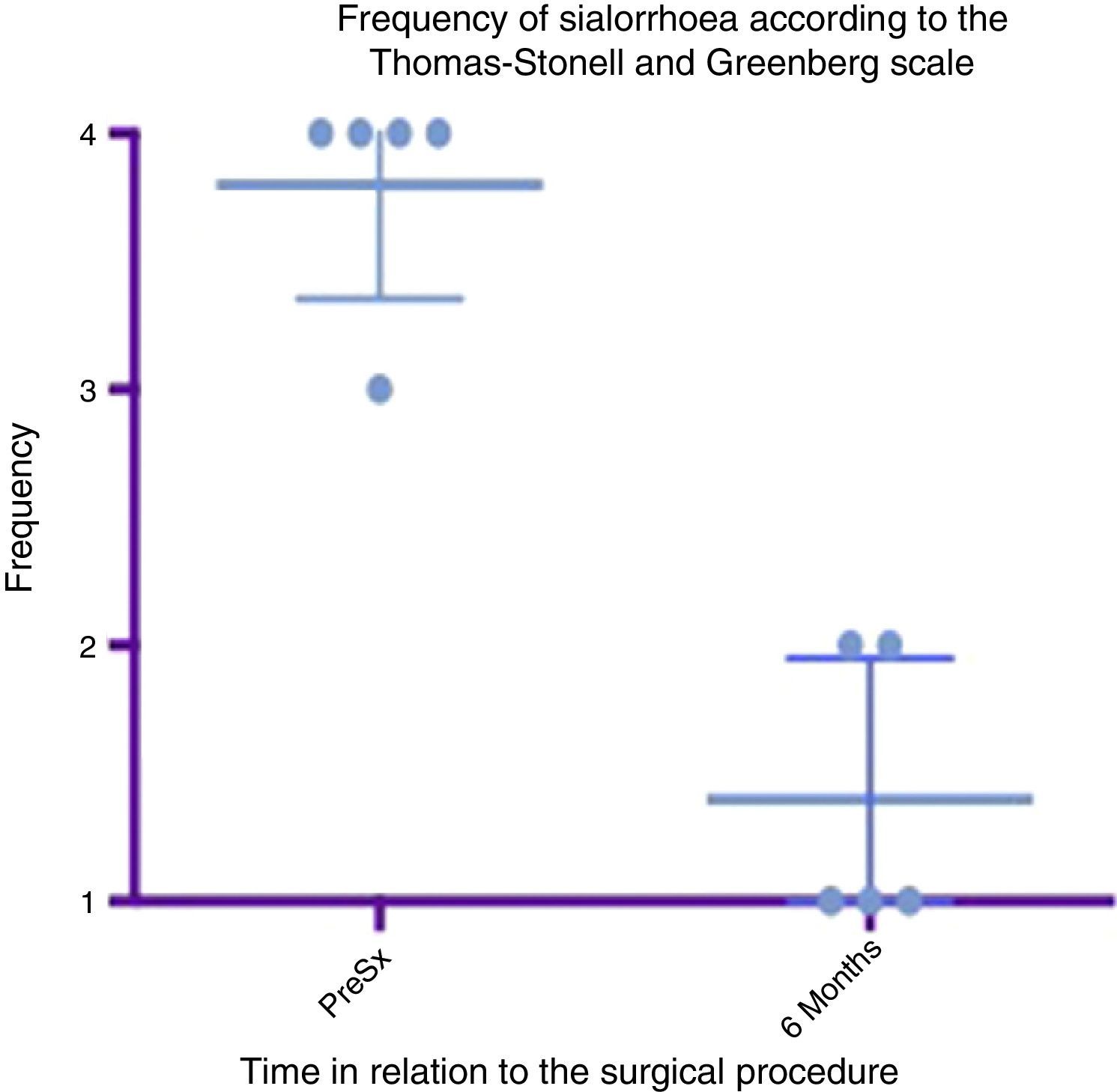

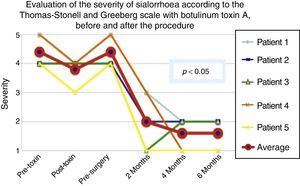

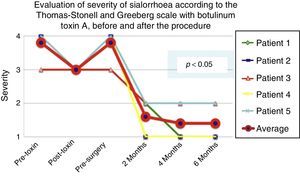

According to the scales, it was evident that after 6 months from the last application of botulinum toxin, the patients had returned to their baseline status in severity and frequency respectively, as is shown in the presurgical stage in Figs. 1 and 2.

Comparison of the improvement shown by the 5 operated patients with regard to severity of sialorrhoea, prior to the first application of toxin (status comparable to pre-surgery), with the maximum effect of the toxin and at 2, 3 and 6 months postoperatively.

Grade 1: never drools. Grade 2: mild (wet lips only). Grade 3: moderate (wet lips and chin). Grade 4: severe (wet clothes). Grade 5: profuse (wet clothing, hands, tray and objects within reach).

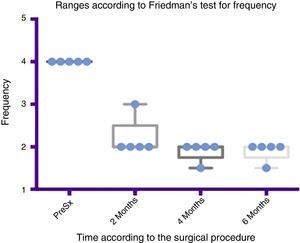

Comparison of the improvement shown by the 5 operated patients with regard to frequency of sialhorrhoea prior to the first application of the toxin (status comparable to pre-surgery), with the maximum effect of the toxin and at 2, 4 and 6 months postoperatively.

Grade 1: never drools. Grade 2: occasionally drools. Grade 3: frequently drools. Grade 4: constantly drools.

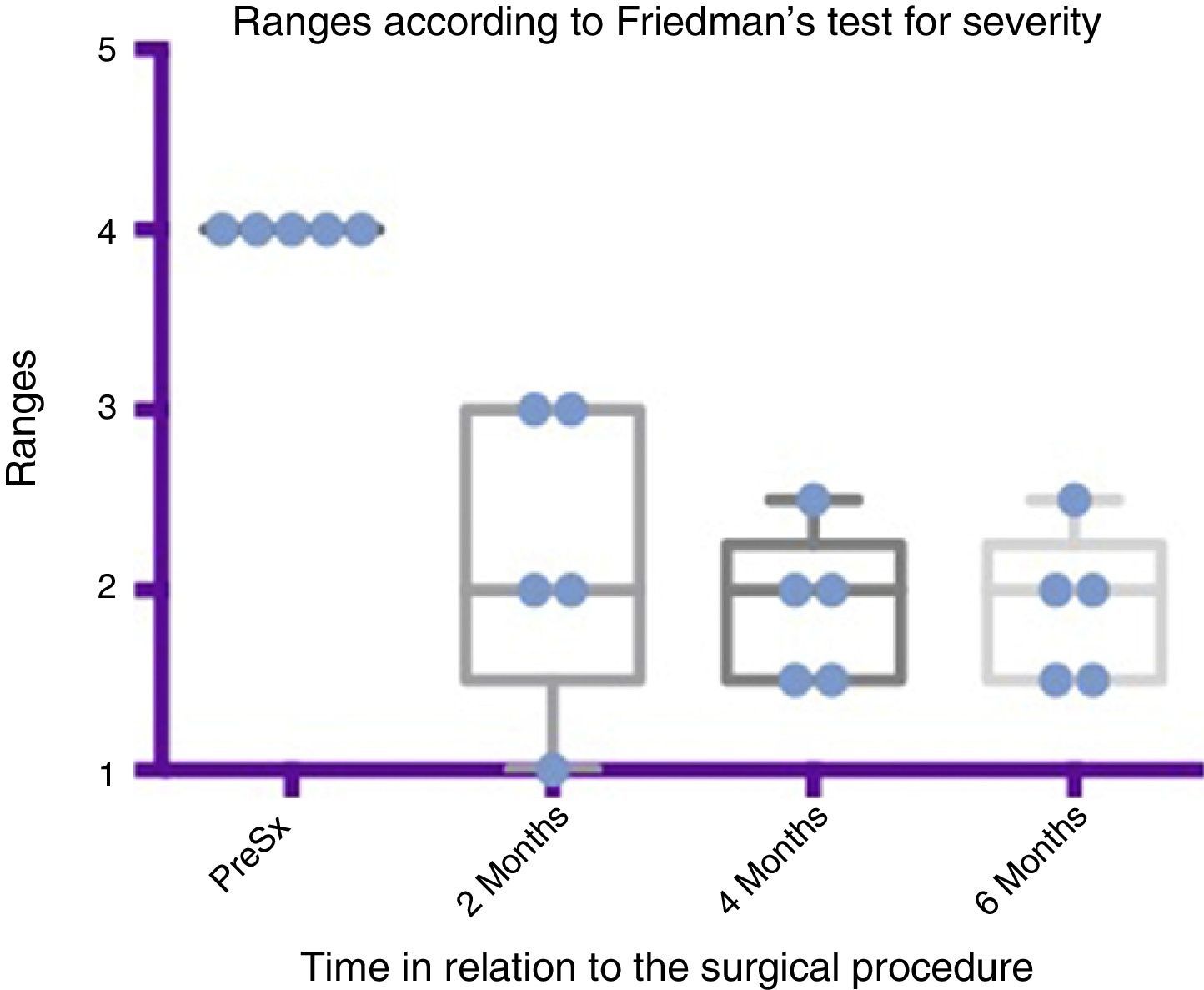

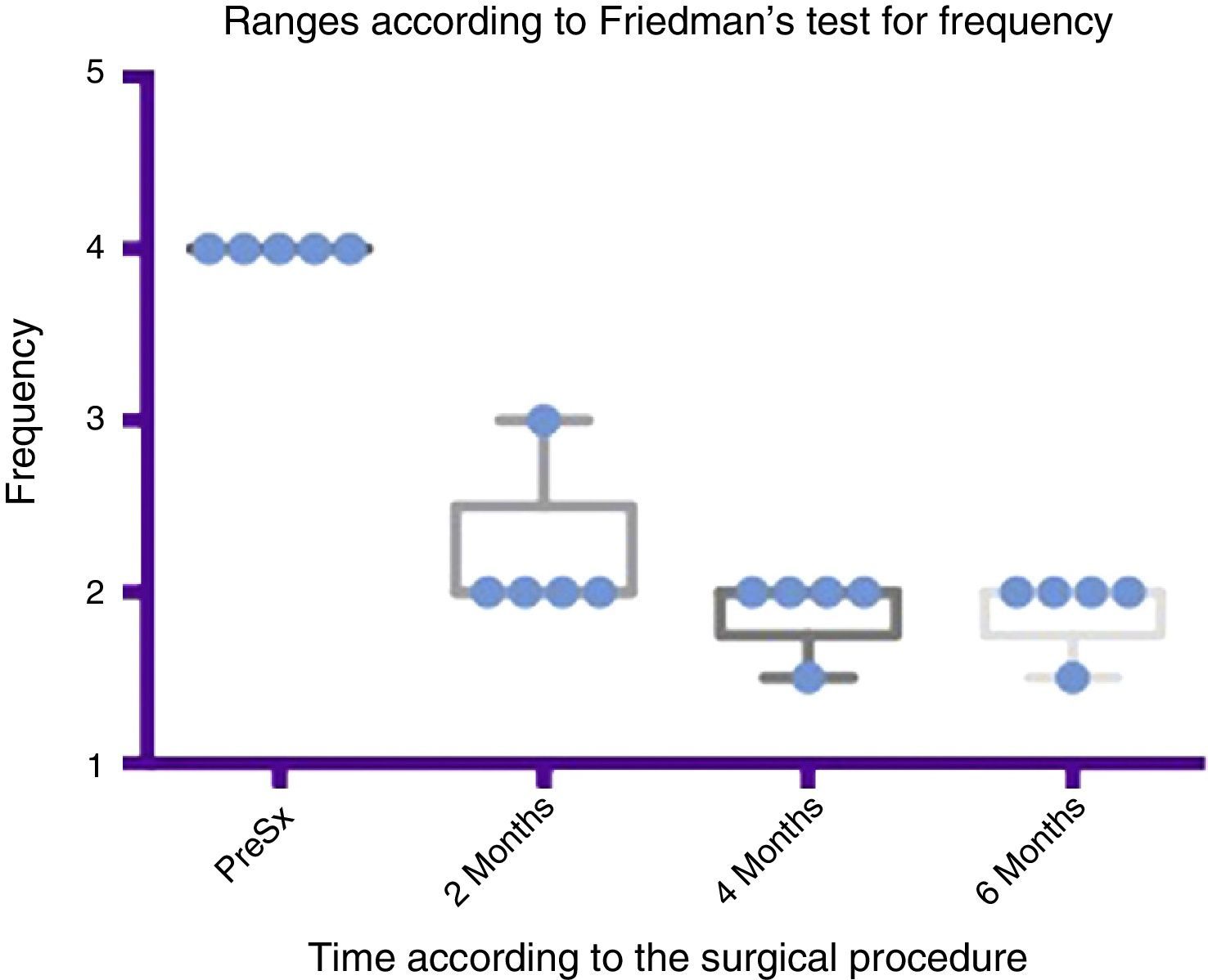

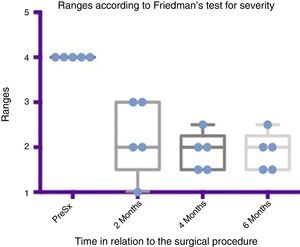

The 5 patients improved substantially, with an average improvement in severity and frequency of sialorrhoea from 2 to 3 grades on the relevant scale, which implies an average reduction in severity of sialorrhoea for the 5 patients of 76.75% and in frequency of 87.5%, with 82.1% efficacy taking into account the sum of averages of improvement in severity and frequency (see Figs. 3 and 4 for severity and Figs. 5 and 6 for frequency).

Comparison by ranges of improvement in severity presented, according to Friedman's test. The minimums and maximums of each period are shown along with the means.

Grade 1: dry. Grade 2: mild (wet lips only). Grade 3: moderate (wet lips and chin). Grade 4: severe (wet clothes). Grade 5: profuse (wet clothing, hands, tray and objects within reach). PreSx=pre-surgery.

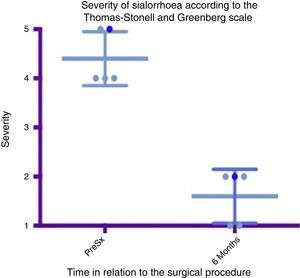

Box and whisker plot showing a comparison of the severity between the preoperative stage and at 6 months postoperatively, taking means and standard deviations into account.

Grade 1: dry. Grade 2: mild (wet lips only). Grade 3: moderate (wet lips and chin). Grade 4: severe (wet clothes). Grade 5: profuse (wet clothing, hands, tray and objects within reach). PreSx=pre-surgery.

Comparison by ranges of improvement in frequency presented, according to Friedman's test. The minimums and maximums of each period are shown along with the means.

Grade 1: never drools. Grade 2: occasionally drools. Grade 3: frequently drools. Grade 4: constantly drools. PreSx=pre-surgery.

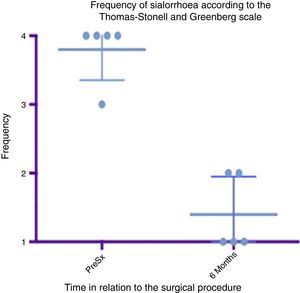

Box and whisker plot showing a comparison of the response found between the preoperative status and at 6 months postoperatively, taking means and standard deviations into account.

Grade 1: never drools. Grade 2: occasionally drools. Grade 3: frequently drools. Grade 4: constantly drools. PreSx=pre-surgery.

Maximum outcome was observed 6 months after the surgical procedure. In the first weeks after surgery, some persistence of sialorrhoea was observed, which was probably associated with pain. By approximately the third post-operative week, the benefit was already evident and was maintained throughout the following six months, except for one patient who went down a point on the severity scale, but remained well in terms of frequency.

Using Friedman's test it was observed that there was a statistically significant difference between the presurgical and postsurgical stage, particularly at 4 and 6 months, with a p=0.0039. Furthermore when the variance analysis was performed, a range analysis was also obtained which showed an obvious difference from the presurgical stage to the first measurement made at 2 months, which was sustained and even discretely improved in subsequent measurements (see Figs. 3 and 5).

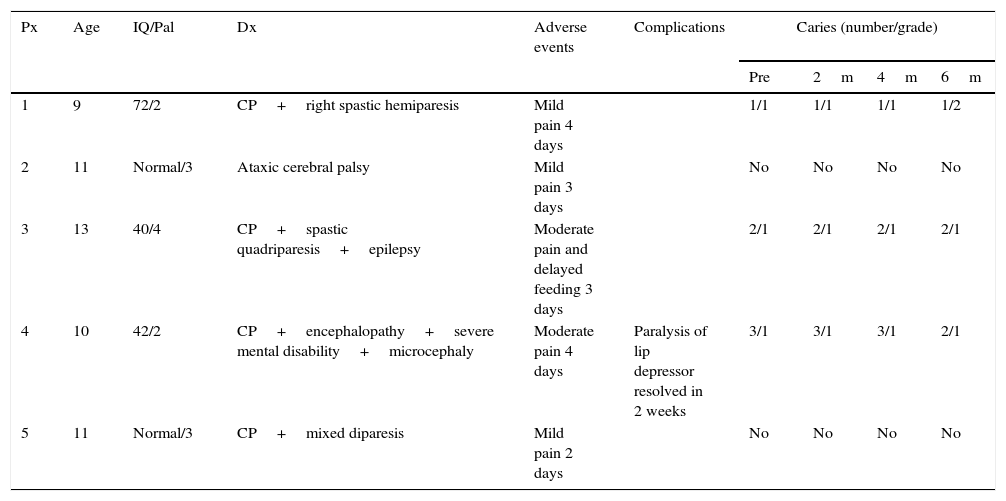

A box and whisker plot comparing the means and standard deviations between the presurgical stage and at 6 months postoperatively shows a major difference between means; both in analysis of severity and that of frequency, and these deviations never cross one another, which implies a significant change between these stages (see Figs. 4 and 6). In terms of complications and adverse events, transient paralysis of the lower lip depressor on the left side was observed in one patient, probably caused by stimulation of the marginal branch of the facial nerve, either by electrical diffusion of the energy generated by monopolar cautery, or by traction of the superior cervical flap. This resolved 14 days after the procedure leaving no sequelae, there was no need for steroids or other medication. No complications were observed in the remainder. Average bleeding in the procedures was quantified at 50ml. No deterioration was seen in the dental condition of the patients at 6 months. Three of the patients had little or mild pain which was resolved in the first 5–7 days, 2 of the patients had moderate pain for the first 7 days and one of the patients took this time to return to normal feeding. The pain improved a great deal with NSAIDs from the seventh day, until it completely disappeared in 10 days (see Table 3).

Patient features, adverse events and complications presented after the surgical procedure and grade of caries observed before and after the procedure.

| Px | Age | IQ/Pal | Dx | Adverse events | Complications | Caries (number/grade) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre | 2m | 4m | 6m | ||||||

| 1 | 9 | 72/2 | CP+right spastic hemiparesis | Mild pain 4 days | 1/1 | 1/1 | 1/1 | 1/2 | |

| 2 | 11 | Normal/3 | Ataxic cerebral palsy | Mild pain 3 days | No | No | No | No | |

| 3 | 13 | 40/4 | CP+spastic quadriparesis+epilepsy | Moderate pain and delayed feeding 3 days | 2/1 | 2/1 | 2/1 | 2/1 | |

| 4 | 10 | 42/2 | CP+encephalopathy+severe mental disability+microcephaly | Moderate pain 4 days | Paralysis of lip depressor resolved in 2 weeks | 3/1 | 3/1 | 3/1 | 2/1 |

| 5 | 11 | Normal/3 | CP+mixed diparesis | Mild pain 2 days | No | No | No | No | |

IQ: intelligence quotient; Dx: diagnosis; Pal: Palisano scale; CP: cerebral palsy; Px: patient.

With regard to changes in the amount or severity of caries, only one patient had an increased grade of caries in one tooth. Apart from that case, no changes were observed at 6 months postoperatively from the baseline status. Regular dental checks and, as a consequence, better dental care, even resulted in a slight improvement in general dental health. Furthermore, the salivary content was analysed in 5 patients over a period of 6–8 months postoperatively and in 2 healthy patients, the latter was to check for errors in sampling and to compare them with the 5 operated patients, as if they were controls. The patients’ levels did not show any significant differences with the 2 controls, all the levels were within normal ranges despite the absence of submandibular saliva. The only electrolyte that showed a tendency to change was calcium which, in general tended towards the lower limits of normality. The latter is to be expected, considering that the saliva produced by the submandibular glands has a slightly higher calcium content than that of the parotid and sublingual glands (see Table 4).

Electrolyte, protein and amylase levels in saliva tested in the cases at 24 months after surgery and in the healthy controls.

| Normal levels | Control 1 | Control 2 | Px. 1 | Px. 2 | Px. 3 | Px. 4 | Px. 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sodium (mEquiv./l) | 18–25 | 21 | 22 | 24 | 22 | 23 | 22 | 26 |

| Potassium (mEquiv./l) | 15–25 | 22 | 24 | 19 | 23 | 20 | 16 | 24 |

| Calcium (mEquiv./l) | 1–5 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Chlorine (mEquiv./l) | 18–25 | 22 | 23 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 23 | 25 |

| HCO3 (mEquiv./l) | 16–22 | 21 | 18 | 20 | 21 | 20 | 18 | 21 |

| Total proteins (mg/ml) | 2–10 | 8 | 6 | 4 | 6 | 4 | 3 | 9 |

| Amylase (U/ml) | 150–600 | 362 | 297 | 425 | 390 | 418 | 325 | 524 |

HCO3: bicarbonate; Px.: patient.

The meta-analysis performed in 2009 by Reed et al.20 on the surgical management of sialorrhoea, gave a combined success rate of the various techniques of 81.6%. The most reported procedure was the relocation of Wharton's ducts in the tongue base, the most effective results were observed with submandibular gland resection and relocation of the parotid ducts in the tonsil bed (subjective success rates: 87.8%). Submaxillary gland resection with ligation of parotid ducts was the third technique with the best results, in terms of effectiveness. Due to the power of the studies and the variability in the number of studies with these techniques, it was concluded that it is not possible to establish a definitive selection criteria between them.

Submandibular resection via a cervical approach is a very familiar technique to ENT surgeons, bearing in mind the management of acute and chronic inflammation and the oncology that can occur in this gland. Working with a familiar technique helps to minimise the possibility of complications arising during the procedure in centres that are new to the management of sialorrhoea.

The average efficacy obtained with a single submandibular gland resection in our 5 patients was 82.1%, which is comparable to that achieved with the best techniques, and the fifth patient that we operated seemed likely to achieve a comparable outcome. There was major improvement in severity and frequency on comparing the baseline status of sialorrhoea with the status at 6 months, this was statistically significant with a p=0.0039 in both analyses, and CI of 95%. Unlike the procedures that involve Stensen's ducts in the parotid glands, such as ligation or rerouting, using this single technique was not detrimental to saliva production, and we eliminated the possibility of parotid sialocele, salivary fistula and the greater pain associated with these techniques.31–33

It is important to bear in mind that leaving a patient with extreme dry mouth will have its own consequences, especially with eating solids, and the maintenance of good lubrication of the oral cavity is a protective factor against the formation of caries and periodontal disease. Therefore, we consider it appropriate to be conservative and only resect the submandibular glands; this enables us to eliminate rest salivation by a theoretical 70%. We also consider it appropriate to ligate the parotid ducts in a second operation for patients who do not respond to the first procedure; this was not necessary. One of our patients had a slightly less favourable response than the others. However, after the procedure he started a new oro-lingual and swallowing therapy and, although this was not useful in principle, with the effect achieved by the procedure the patient managed to control the sialorrhoea that he was left with and his carers were satisfied with the result.

As mentioned earlier, no increase in the number of caries or periodontal disease was observed in the operated patients. It is important to mention that during their participation in the study, the patients improved their dental care, and we consider this sufficient to avoid the increase in dental plaque bacteria, caries and periodontal disease found in other studies.

No major electrolyte, protein or enzyme changes were observed in salivary composition; therefore we consider that submandibular gland resection largely respects the physiological production of saliva.

The preliminary results of this study show that submandibular sialadenectomy in experienced hands is a procedure with a good safety profile and low potential for complications. It is very useful in the management of profuse sialorrhoea in patients with cerebral palsy, because it significantly reduces both its severity and frequency. It is important to continue this study to obtain more data on safety and efficacy, given that the sample in this pilot study is small and therefore, not significant.

The good result in paediatric cerebral palsy patients indicates that this technique might be equally useful in other neurological conditions that produce sialorrhoea such as, lateral amyotrophic sclerosis, Parkinson's disease or the sequelae of a cerebrovascular event; therefore we propose that studies of these characteristics should be performed on these different types of patients.

ConclusionsSubmandibular gland resection is an effective technique for the control of sialorrhoea in paediatric patients with cerebral palsy, with outcomes of around 80% effectiveness.

It is a technique with a low rate of complications, unlike the techniques that involve the parotid gland, where the pain is more severe due to the possibility of sialoceles, and the techniques of duct relocation to the tongue base, where oedema can compromise the airway and return to normal feeding can take longer.

Resecting the submandibular glands resulted in sufficient and detectable reduction in sialorrhoea, without the need to work on the other major salivary glands. This benefit was especially clear with rest salivation, which most afflicts these patients.

None of the patients presented an increase in dental disease, dry mouth or problems with feeding. We consider that parotid salivation was not affected by the surgical procedure.

It is necessary to broaden our experience to obtain appropriate safety and efficacy parameters for the technique, but the outcomes in these first 5 patients have encouraged us to consider this technique the management standard in our centre.

It would be equally useful to test the effectiveness and safety of other techniques of proven efficacy in our patients, and contrast them with those that we currently use, to evaluate which is really the best available technique in the management of sialorrhoea.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that neither human nor animal testing have been carried out under this research.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have complied with their work centre protocols for the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patients’ data appear in this article.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

We thank Dr. Olga Beltrán Rodríguez-Cabo and Dr. Mario Sergio Dávalos Fuentes for their collaboration in the study.

Please cite this article as: Hernández-Palestina MS, Cisneros-Lesser JC, Arellano-Saldaña ME, Plascencia-Nieto SE. Resección de glándulas submandibulares para manejo de sialorrea en pacientes pediátricos con parálisis cerebral y poca respuesta a la toxina botulínica tipo A. Estudio piloto. Cir Cir. 2016;84:459–468.