Radiofrequency ablation (RFA) is a safe and effective treatment option for patients with unresectable hepatic tumors, which are destroyed by coagulative necrosis. Nonetheless, complications may appear due to mechanical or thermal damage1,2 although these are not usually life-threatening. This article describes a severe complication of this treatment.

A 43-year-old male patient was sent to our department for treatment of hepatic metastases. The patient's prior medical history included allergy to penicillin, GIST of the small intestine that was surgically removed twice and treatment with imatinib 400mg/day since the initial surgery (three years before). At that time, blood test results (biochemistry, coagulation, hemogram, tumor markers) were normal and computed tomography (CT) showed a total of eight hepatic metastases in both lobes. The patient underwent surgery, and eight atypical hepatic resections and cholecystectomy were performed.

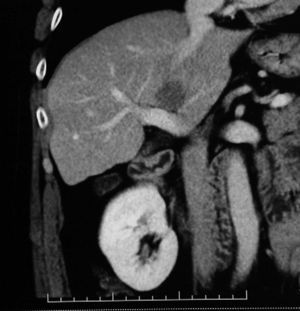

Two years later, and despite continuing with chemotherapy with imatinib 800mg/day, the patient presented with a new hepatic metastasis seen on CT, although on this occasion it was very badly situated between the cava, hepatic hilum and suprahepatic veins (Fig. 1). Given the lack of response to treatment and the stability of the lesion, the patient underwent surgery. After liver mobilization, it was observed that the lesion was in contact with the portal vein and its branches, cava and suprahepatic veins. With manual, visual and ultrasound confirmation, we therefore decided to treat it with RFA and clamping of the pedicle for 12min, reaching a temperature above 70°C. On the second post-op day, the patient presented tachypnea, dyspnea and oliguria, metabolic acidosis with respiratory compensation and blood tests showing severe hepatic and renal damage (GOT 9900, GPT 4224, INR 3, creatinine 2.3, platelets 108,000). The patient was admitted to the ICU for intensive monitoring and treatment of coagulopathies and renal failure, while receiving support for liver failure. After abrupt desaturation that required intubation, pulmonary thromboembolism (TEP) was ruled out with transesophageal echocardiogram. The abdomen was distended and defended. Abdominal Doppler ultrasound demonstrated an area of liver infarction and portal vein thrombosis. The patient required antibiotic therapy, hemofiltration and massive transfusion due to the worsening coagulopathy and thrombopenia. The patient's condition progressed to multiple organ failure, requiring intensive inotropic support, and the electroencephalogram was suggestive of hepatic encephalopathy. On the fourteenth post-op day, the patient died.

The aim of RFA is to produce an area of necrosis that is large enough to encompass the hepatic tumor with a safety margin (at least 0.5cm in order to impede the persistence or progression of the tumor). The size of the necrosis is determined by several factors, including the size of the electrode and thickness, temperature and duration.3,4

The effectiveness of RFA decreases when the lesion is in the proximity of large blood vessels (larger than 3mm in diameter) due to the refrigerating effect of the blood flow. In these cases, it has been observed that the suppression of the flow (not only by surgical clamping using the Pringle maneuver, but also with occlusion by means of a catheter) to the area of the lesion increases the size of the ablation by concentrating the temperature, which improves tumor-free margins.5,6

RFA complications may range from 0 to 12.7% (according to different reports), and are generally due to infection or bleeding. Complications are classified into two categories: major and minor. Major complications are those which are life-threatening if not correctly treated, increasing morbidity, mortality and hospital stay. Minor complications are more frequent7 and may include:

- -

Vascular: portal vein thrombosis, hepatic vein thrombosis, liver infarction (very uncommon due to the double hepatic vascularization from the portal vein and the hepatic artery), subcapsular hematoma (more frequent in cirrhosis and patients with altered coagulation), etc.

- -

Biliary: stenosis of the bile duct and biloma (due to heat damage), abscesses (the most common in some series), hemophilia, or even peritoneal bleeding, etc.

- -

Extrahepatic: gastrointestinal tract lesions, vesicular lesions (cholecystitis, more than perforation), hemothorax and pneumothorax, tumor dissemination, skin burns, etc.

The best strategy for reducing complications is considered to be the correct selection of cases, taking into account liver function (Child–Pugh class B or C increases the risk for liver failure after RFA), the lesion itself (size, location, etc.), as well as the type of approach.

Most complications can be treated conservatively with antibiotics, percutaneous drainage or endoscopically, although surgical intervention is sometimes necessary.8

Liver infarction is a rare complication of RFA (although somewhat more common if percutaneous ethanol injection or arterial embolization are previously used) that may become fatal, although deaths have rarely been reported9 (we have found only one case). It is believed that at least arterial liver vascularization needs to be affected for a fatal outcome, but many authors argue that altered portal vein vascularization also needs to be associated.

The Pringle maneuver may not be necessary for RFA of all liver tumors, but it is an option in large tumors that are very vascularized or proximal to large blood vessels. Nevertheless, it should be done with caution as direct thermal damage may affect the vascular or bile structures as well as the parenchyma adjacent to the area of ablation (Fig. 2), which is increased with the lack of blood flow.10

Although the pathogenesis of hepatic infarction is not completely clear, it is important to consider this rare but fatal complication.

Please, cite this article as: Ladra González MJ, et al. Infarto hepático masivo tras ablación por radiofrecuencia. Cir Esp. 2013;91:122–4.