Advanced age and comorbidity impact on post-operative morbi-mortality in the frail surgical patient. The aim of this study is to assess the impact of a comprehensive, multidisciplinary and individualized care delivered to the frail patient by implementation of a Work Area focused on the Complex Surgical Patient (CSPA).

MethodsRetrospective study with prospective data collection. Ninety one consecutive patients, classified as frail (ASA III or IV, Barthel<80 and/or Pfeiffer>3) underwent curative radical surgery for colorectal carcinoma between 2013 and 2015. Group I: 35 patients optimized by the CSPA during 2015. Group II: 56 No-CSPA patients, treated prior to CSPA implementation, during 2014–2015. Group homogeneity, complication rate, length of stay, reoperations, readmissions, costs and overall mortality were analyzed and adjusted by Diagnosis-Related Group (DRG).

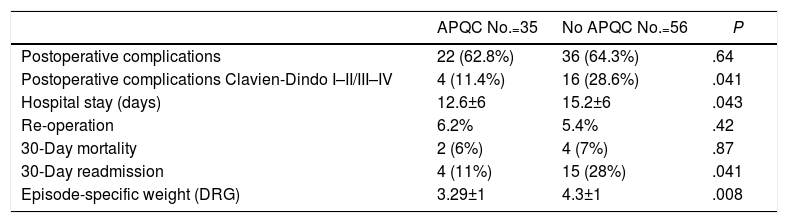

ResultsThere were no statistically significant differences in term of age, gender, ASA classification, body mass index, tumor staging and type of surgical intervention between the two groups. Major complications (Clavien-Dindo III–IV) (12.5% vs 28.5%, P=.04), hospital stay (12.6±6days vs 15.2±6days, P=.041), readmissions (12.5% vs 28.3%, P<.041), and patient episode cost weighted according to DRG (3.29±1 vs 4.3±1, P=.008) were statistically inferior in Group CSPA. There were no differences in reoperations (6.2% vs 5.3%) or mortality (6.2% vs 7.1%). 96.9% of patients of Group I manifested having received a satisfactory attention and quality of life.

ConclusionsImplementation of a CSPA, delivering surgical care to frail colorectal cancer patients, involves a reduction of complications, length of stay and readmissions, and is a cost-effective arrangement.

La edad avanzada y la presencia de comorbilidades repercuten en la morbimortalidad postoperatoria del paciente quirúrgico frágil. El objetivo de este estudio es valorar los resultados de morbimortalidad tras cirugía por cáncer colorrectal en el paciente quirúrgico frágil tras la implementación de un Área de Atención al paciente Quirúrgico Complejo (AAPQC).

MétodosEstudio retrospectivo con recogida prospectiva de datos. Un total de 91 pacientes consecutivos considerados como frágiles (ASA IV o ASA III con Barthel<80 i/o Pfeiffer>3) fueron intervenidos entre 2013 y 2015 con diagnóstico de cáncer colorrectal con intención curativa. Grupo I (AAPQC): 35 pacientes incluidos en AAPQC durante 2015. Grupo II (No AAPQC): 56 pacientes intervenidos entre 2013 y 2014 previa implementación del AAPQC. Se analizó homogeneidad de grupos, complicaciones, estancia media, mortalidad, reintervenciones, reingresos y costes en función del GRD.

ResultadosNo se encontraron diferencias significativas en edad, sexo, ASA, índex de masa corporal, estadio tumoral y tipo de intervención quirúrgica entre los dos grupos. Las complicaciones mayores (Clavien-Dindo III-IV) (11,4% vs 28,5%, p=0,041), la estancia media (12,6±6días vs 15,2±6 días, p=0,043), los reingresos (11,4% vs 28,3%, p=0,041) y el peso específico del episodio (3,29±1 vs 4,3±1, p=0,008) fueron significativamente menores en el grupoAAPQC. No hubo diferencias en re intervenciones (6,2% vs 5,3%) ni mortalidad (6,2% vs 7,1%). El 96,9% de pacientes del grupo I manifestó una atención y calidad de vida satisfactoria.

ConclusionesLa implementación de una AAPQC en pacientes frágiles que deben ser intervenidos de cáncer colorrectal comporta una reducción de las complicaciones, estancia y reingresos, y es una medida coste-efectiva.

The increase in life expectancy inexorably leads to an increasingly aging population, which in turn leads to increased comorbidity. Both aspects are not contraindications for surgery by themselves, but they have an enormous impact on complications and decision-making, which is made more complex.1,2 Consequently, it is imperative to develop strategies to guarantee adequate quality care for geriatric surgical patients as well as non-geriatric patients with high comorbidity and associated frailty. We define frailty as the decrease in the physiological reserve of multiple organ systems that involves increased risk of disability and death as a result of stress.3–5

Several studies have demonstrated the effects of advanced age, comorbidity and frailty on morbidity and mortality in the postoperative period (even after 30 days) of patients who should undergo cancer surgery.6–12 This usually leads to an increase in hospital stay, excessive and inappropriate consumption of resources, and sometimes unwanted or at least questionable results in quality of life and even survival.8–12 Under these conditions, an associated progressive deterioration of the doctor-family relationship is not uncommon, and finally we may question whether the initial therapeutic decision was the most appropriate. These results could be improved by earlier detection of these patients in order to offer them individualized care according to their physical, mental and social status by a multidisciplinary team that would assume the responsibility of the entire process in a cohesive manner. We propose the creation of a Complex Surgical Patient Work Area (CSPA) to direct the entire process and manage resources until the patient returns to Primary Care. The aim of this present study is to analyze whether the management of fragile patients with colorectal cancer by an CSPA would reduce complications, re-admission rates and, consequently, costs, and whether it would facilitate decision-making and improve the level of satisfaction and quality of life of these patients.13,14

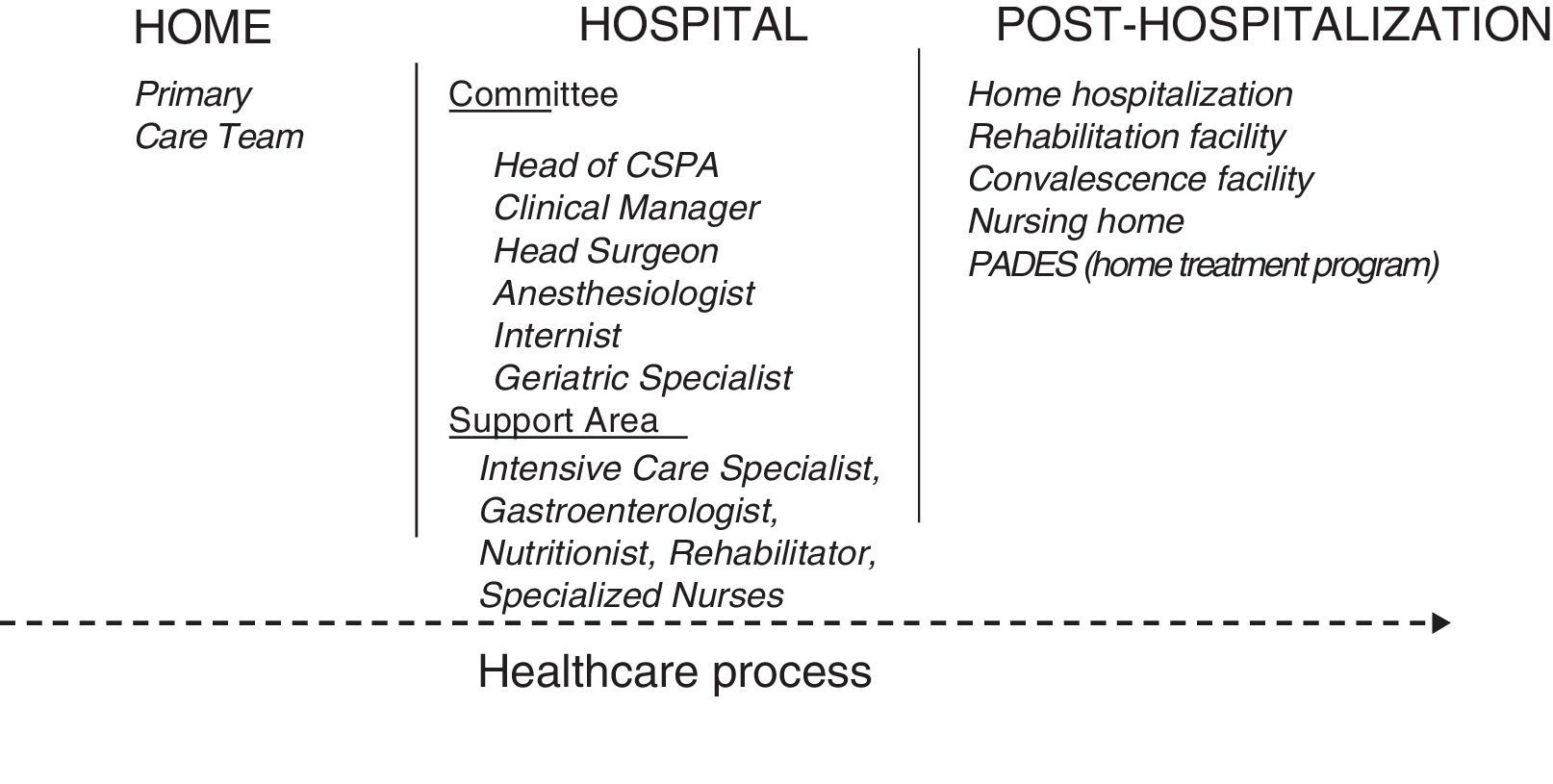

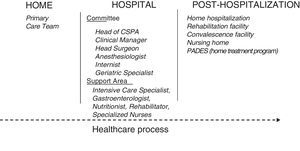

MethodsStructure and Composition of the Complex Surgical Patient Care AreaThe CSPA is subdivided into:

- -

CSPA Committee: evaluates the case, decides optimal treatment before surgery, suggests the anesthesia and surgical procedure, predicts possible intra- and post-hospital resources and follows the patient during hospitalization.

- -

Support area: professionals who will provide specific support in accordance with the decisions and evaluations of the Committee (Fig. 1).

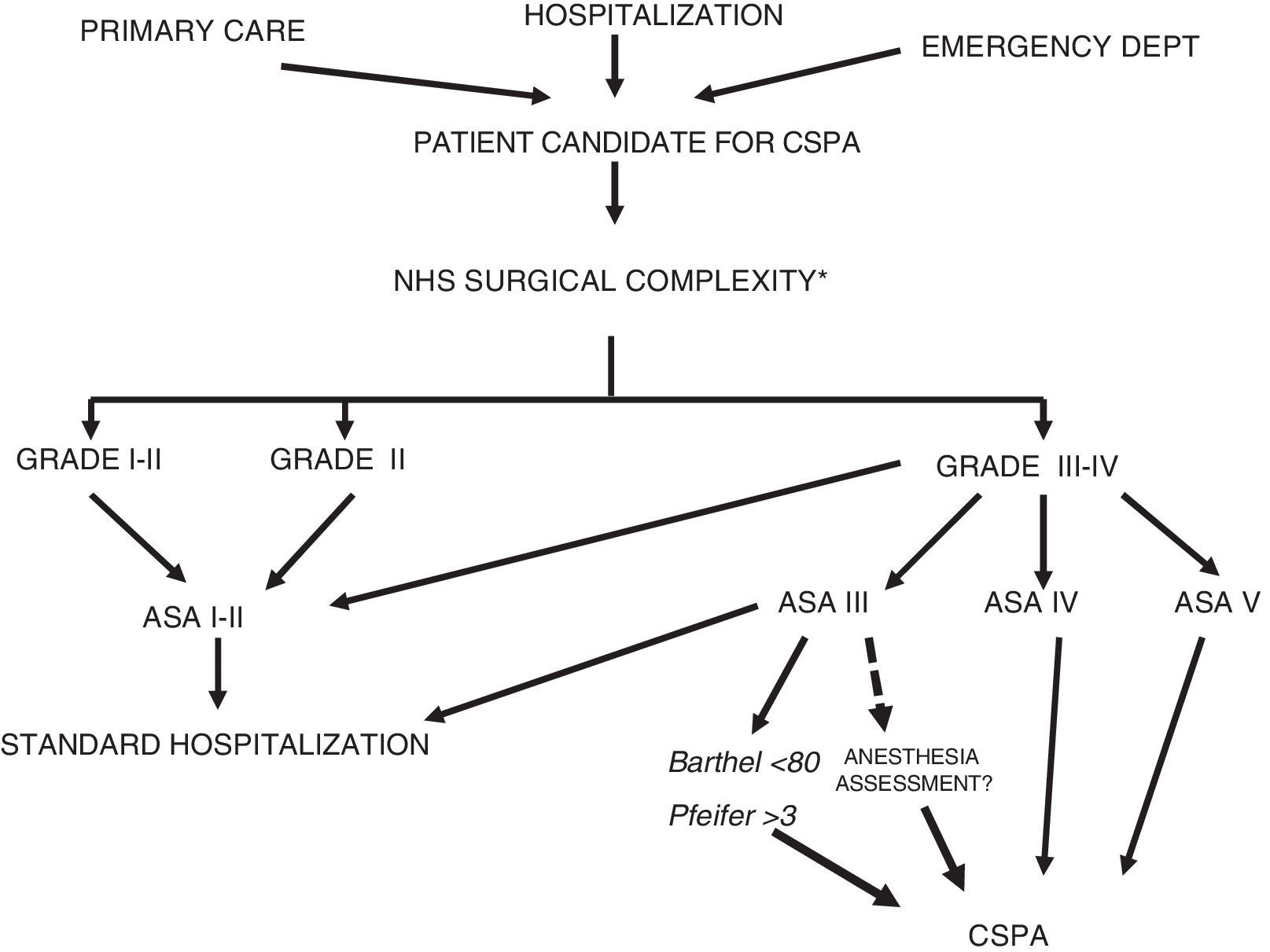

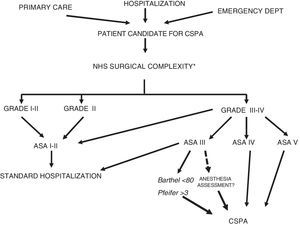

Ours is a retrospective, observational case and control study with prospectively collected data from our hospital management computer system (SAP). We included patients with colorectal cancer, candidates for surgery with curative intent and with frailty criteria based on 4 risk factors: surgical (NHS scale III or IV15), anesthetic (ASA classification III or IV16), functional (Barthel <7017) and cognitive (Pfeiffer >3 errors) (Fig. 2). Patient nutritional and anemic status was assessed, and patients were divided into two groups: Group I (study group), 35 patients included in the CSPA in 2015; and Group II (control group), 56 patients with the same characteristics treated surgically in 2013–2014 (prior to the establishment of the CSPA). Data were analyzed for demographics, ASA, body mass index (BMI), tumor stage, type of surgery, complications, stay, reoperations, mortality (30 days), re-admissions and specific weighted diagnosis (GRD). In Group I, a health quality test was applied (EQ-5D, after 90 days post-op), which was interpreted based on the status prior to surgery. In Group 1, quality of life was also subjectively assessed using the questions: “Is your current status better, equal or worse than prior to surgery?” and “Are you very satisfied, satisfied or dissatisfied with the care offered?” Four patients were excluded: 2 due to diffuse carcinomatosis and 2 cases that were ruled out for surgery by the committee due to high comorbidity.

The implementation of the CSPA and study design were approved by the Healthcare Ethics Committee, emphasizing that this new integrated care promotes the respect for the autonomy and decisions of patients.

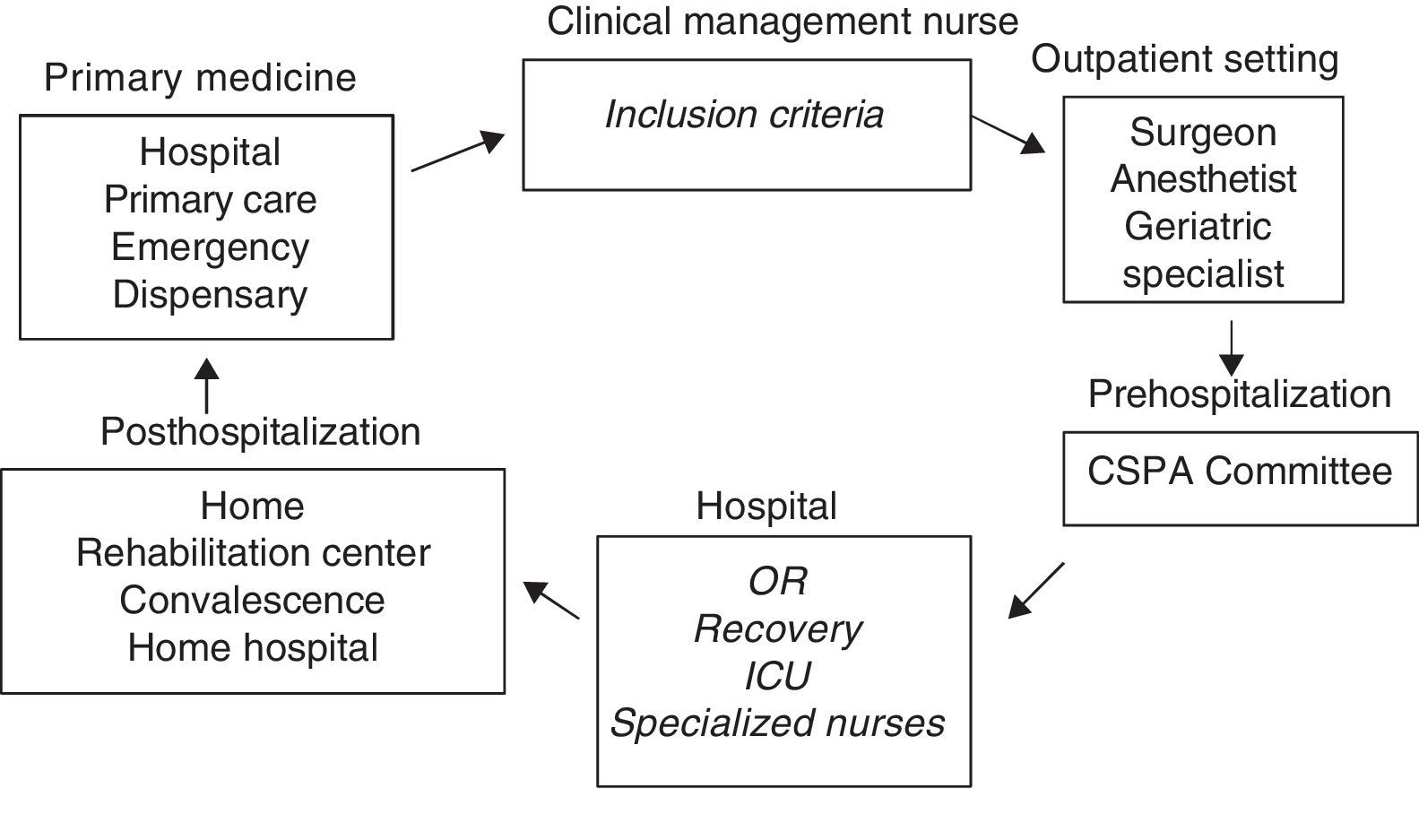

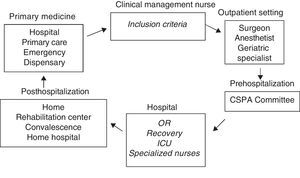

Process CircuitPossible candidate patients (primary care, outpatient consultations, hospital) were assessed by the advanced practice nurse (process manager). Patients who met the frailty criteria were assessed by the area-specific surgeon and anesthetist and were subsequently brought before the committee for evaluation and to define the optimal treatment. After optimization (period pre-established by the committee), the committee evaluated the response and preparations were initiated by activating the resources for the intervention, the postoperative period and even the return to home. The patients and their families were again informed of the decisions, an agreement was reached about whether the limitation of the therapeutic effort was opportune, and consent forms were signed. A single team meant that the circuit time could be reduced as much as possible (Fig. 3).

During the entire process, there was direct communication between the CSPA (facilitated by the nurse manager) and the primary care physicians (who usually attended the committee meetings when their patients were presented). There was also information, consensus and a constant relationship with the Complex Chronic Patient Unit of our institution, and with the Home Palliative Unit in case of need.

Creation of FormsStandardized forms were created to present the cases to the committee, to give specific informed consent for surgery, to limit the therapeutic effort (also including aggressive measures that should not be performed in case of complications derived from the procedure, such as reintubation, admission to the ICU and reoperation), and finally to declare non-acceptance (by the patient and family) of any aggressive therapeutic approach if this was the decision made. In addition, complete explanations were given about the measures to be carried out in case of complications arising over the natural course of the disease.

Statistical AnalysisThe statistical analysis was calculated with the SPSS v20.1 statistical software. The categorical variables were analyzed with Pearson's chi-squared test and the comparison of the continuous variables involved the Student's y test after performing the Kolmogorov–Smirnov normality test.

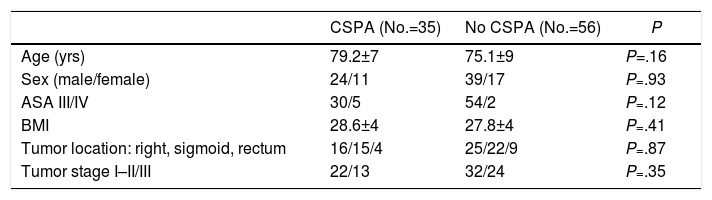

ResultsThere were no significant differences between the two groups in terms of age, sex, ASA, BMI, type of surgery and tumor stage (Table 1). The overall complication rates were similar (62.8% vs 64.3%, P=.66). Major complications (Dindo III–IV) (11.4% vs 28.5%, P=.041), hospital stay (12.6±6 days vs 15.2±6 days, P=.043), re-admissions (11.4% vs 28.3%, P=.041) and specific weight of the episode (3.3±1 vs 4.3±1, P=.008) were significantly lower in Group I (Table 2). There were no differences in the rate of reoperations (6.2% vs 5.3%, P=.42) or in mortality (6.2% vs 7.1%, P=.87). In Group I, the overall subjective quality of life after 90 days was very satisfactory in 27/33 patients (81.8%), satisfactory in 5/33 (15.1%) and unsatisfactory in 1/33 (3.1%); 100% said they were very satisfied with the care received.

Characteristics of the Patients and Tumors; Data are Expressed as Number of Patients or Mean±Standard Deviation.

| CSPA (No.=35) | No CSPA (No.=56) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yrs) | 79.2±7 | 75.1±9 | P=.16 |

| Sex (male/female) | 24/11 | 39/17 | P=.93 |

| ASA III/IV | 30/5 | 54/2 | P=.12 |

| BMI | 28.6±4 | 27.8±4 | P=.41 |

| Tumor location: right, sigmoid, rectum | 16/15/4 | 25/22/9 | P=.87 |

| Tumor stage I–II/III | 22/13 | 32/24 | P=.35 |

BMI: body mass index.

Significant Differences in Complications, Hospital Stay, Readmission and GRD Code.

| APQC No.=35 | No APQC No.=56 | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Postoperative complications | 22 (62.8%) | 36 (64.3%) | .64 |

| Postoperative complications Clavien-Dindo I–II/III–IV | 4 (11.4%) | 16 (28.6%) | .041 |

| Hospital stay (days) | 12.6±6 | 15.2±6 | .043 |

| Re-operation | 6.2% | 5.4% | .42 |

| 30-Day mortality | 2 (6%) | 4 (7%) | .87 |

| 30-Day readmission | 4 (11%) | 15 (28%) | .041 |

| Episode-specific weight (DRG) | 3.29±1 | 4.3±1 | .008 |

In Group I, according to the EQ-5D test, 90% of patients had a degree of mobility, personal care, activity and depression or anxiety similar to that prior to surgery. In one case complicated by hematoma of the medullary canal after positioning of the epidural catheter, the EQ-5D test obtained the minimum score due to paraplegia secondary to the complication. In 100% of the cases, the patients declared that they were very satisfied with the care received. In 7 cases, given the enormous comorbidity and its poor baseline status, consent to limiting the therapeutic effort was signed before surgery.

DiscussionOptimization and coordination of the entire management process of fragile patients requiring surgery improves results and benefits both patients and institutions.11,12,18–24 Thus, when patient care is cohesive and coordinated, we are able to create a model in which patients travels through the health care process in the simplest way possible. This is the basis and justification of the CSPA (Fig. 1).

This integrated care originates in the outpatient setting and provides a better understanding of the patient's physical and social status and anticipates the possible needs and resources available upon returning home. To this end, there must be a fluid relationship with primary care physicians and support, including both by computer and direct communication. Individualized, multidisciplinary, preoperative care should always be coordinated and conducted by the same professionals and provide extensive information for all factors that may influence the decision-making process and optimization of patients for surgery. These same professionals will be responsible for patient care at all times during the hospitalization period and will anticipate the patients’ medical and social needs at the end of the hospitalization stage. Determining these needs in advance in a coordinated manner given the resources available has allowed us to considerably reduce the length of hospital stay.

Surgically-treatable pathologies that arise in this type of patients (mainly neoplasms) cause decompensation of their comorbidity and severe deterioration of their baseline status (nutritional status, anemia, mobility, etc.) that should be optimized preoperatively as quickly as possible.20–24 The basic pillar for the care of these patients is the CSPA Committee itself, a small multidisciplinary group that assists patients during the entire hospital phase. Furthermore, given the very small number of cases, these patients are admitted (after consulting with the hospital admissions department) to one of the rooms the Surgery Department has available for isolated patients. Conventional nursing care together with the help of the nurse manager is sufficient to not require an increase in resources.

Due to their complexity, these patients should not be evaluated and treated by different professionals within the same specialty. The role of the anesthetist in the initial assessment is essential (in accordance with the decisions made by the Committee) in order to optimize intra- and postoperative anesthesia. The contribution of the geriatric specialist in many instances is able to evaluate the degree of cognitive and functional alterations, which are frequently underestimated by other specialists; sometimes, his/her evaluation leads to the dismissal of an intervention that would probably be doomed to failure, thereby avoiding subsequent patient suffering and the unnecessary consumption of resources.11,12,20,23 The presence of an internist with projection of surgical knowledge provides better support throughout the hospital stay. We also think that it is of vital importance that the chosen surgeon be visible and responsible throughout the entire process (diagnosis, information, presentation to the area, intervention and follow-up). Surgery must be painstakingly precise, and for this a surgeon with great experience is necessary. Finally, the presence of a highly experienced clinical nurse is essential to coordinate the entire process: relationship with the patient and family, medical professionals, studies, decisions, pre- and postoperative needs, and continuity of care with primary care.25

Decisions regarding the treatment to be carried out, steps to perform during the process and limits of the therapeutic effort made by this committee are adequately explained, agreed upon, accepted, consented to and signed by the patient and written in the patient file. In the event that the patient is not able or competent (and only under these circumstances), information, communication, consensus and consent actions will be assumed by the closest relative or the person representing the patient. In our series, the therapeutic effort limitation was signed in 7 cases (two died). This greatly facilitates the actions and decision-making of professionals in cases of need and, as a result, sometimes avoids non-essential therapeutic efforts.26–30 In the same way, if the treatment is rejected, a document should be prepared, consented and signed by both parties for steps to take in case of complications in the evolution of the disease, in order to avoid heroic actions that are often disproportionate (in two cases, the committee dismissed the surgical intervention due to high fragility and proceeded to create this document). Faced with this situation, the surgeon in charge refers the patient to a specialized team for the treatment and control of symptoms, while the advanced practice clinical nurse informs Primary Care to prepare the necessary resources.

In the analysis of the results, the complications were high and similar in both groups, as expected. However, patients of the CSPA had fewer major complications (Dindo III and IV). The number of reoperations and surgical complications was extremely low and similar in both groups. Therefore, these differences could be attributed to medical complications secondary to the intervention and not to the surgeon factor. Probably, the detection and prevention actions were carried out in the CSPA group could explain these differences. The hospital stay would be in accordance with the lower number of complications on one hand and, on the other, this integrated care provides the necessary resources for patient care at discharge, whether at home, convalescence or a social-healthcare center.

Finally, it seems clear that a patient with fewer complications and a shorter hospital stay would have a lower DRG code; consequently, the costs, at least at the hospital level, would be much lower. It is evident that the cost analysis did not include the extrahospital part of the process, and this is a study limitation. However, doing so would be enormously difficult. On the other hand, we want to emphasize that there has been no need to increase resources, since the CSPA is comprised of professionals from the institution itself and Primary Care working in their respective services. However, an immense effort in coordination was necessary. Agreement on and consent to limitations of the therapeutic effort in the event of poor patient progress, as well as consensus on the therapeutic actions to be taken in cases of complications when the surgery has not been carried out, greatly facilitate the work of medical professionals as well as the acceptance by patients and their families.

Finally, it should be noted that prolonged hospital stays together with a high number of complications often leads to a progressive deterioration of the family's relationship with physicians, whose professionalism and care management are questioned. The quality of life and satisfaction results advocate implementation of the CSPA. While it is difficult to objectively express the degree of satisfaction, in this study we have established two simple and comprehensible questions. In these terms, the results have been good and acceptable. No treatment complaints were lodged, which are otherwise frequent in these patients.

Based on the preliminary results analyzed, we are currently developing quality indicators (% of complications, stay, readmissions, etc.). We believe these are essential to continuously evaluate the work carried out. On the other hand, it would be interesting (after a greater number of patients included) to be able to define a score that would allow us to predict which patients would be doomed to failure and likely have a worse quality of life. However, many more studies are required with a larger number of patients. It is a new field of work and research, and we believe it opportune to publish our results with the intention of encouraging other groups and be able to determine what factors would allow us to predict which patients are destined for failure.

The treatment of these patients is complex, prolonged and sometimes tiring. It requires medical professionals with character who are motivated, skilled, tenacious and intend to progress in this novel field. Only under these conditions will we obtain satisfactory results for patients, their families and doctors, and probably a rationalization of resources. In conclusion, the implementation of a CSPA that provides cohesive multidisciplinary, individualized, continuous care results in reduced complications, hospital stay, readmissions and costs throughout the entire healthcare process, with an acceptable quality of life and degree of satisfaction.

Conflict of InterestsWe have no conflict of interests to declare.

The authors would like to thank Dr. R. Jorba Martín, Clinical Director of the Hospital Joan XXIII of Tarragona, initial promotor of this project.

Please cite this article as: Castellví Valls J, Borrell Brau N, Bernat MJ, Iglesias P, Reig L, Pascual L, et al. Resultados de morbimortalidad en cáncer colorrectal en paciente quirúrgico frágil. Implementación de un Área de Atención al Paciente Quirúrgico Complejo. Cir Esp. 2018;96:155–161.

All the authors of the manuscript are part of and actively participate with the CSPA Committee.