Disconnected pancreatic duct syndrome (DPDS) or disconnection of the pancreatic duct involves a discontinuity between a portion of viable pancreas and the gastrointestinal tract, which is caused by duct necrosis after severe pancreatitis or pancreatic trauma. It was first described by Kozarek in 1991,1 and it appears when the isolated pancreatic segment continues to have an exocrine function, thereby leading to recurrent collections or pancreatic fistulas. It occurs predominantly in the region of the neck of the pancreas, which causes the remnant of the body or tail of the pancreas to secrete pancreatic juices to the retroperitoneum. The diagnosis is generally made by computed tomography, which demonstrates an unperfused area of the neck, body or tail of the pancreas. However, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) is recommended to demonstrate the discontinuity of the duct or extravasation of contrast material.2 Nuclear resonance imaging can also be used and would avoid the potential risk for infection of the pancreatic necrosis.3 Nonetheless, in spite of imaging studies, the diagnosis is frequently delayed, and differential diagnosis should be made between DPDS and patients with pancreatic pseudocysts. As for treatment, there is still much controversy about which option is optimal.4

We present the case of a 45-year-old male patient, former alcoholic, with a history of chronic alcoholic pancreatitis and several episodes of re-exacerbation as well as cholecystectomy. The patient reported invalidating pain in the left hemiabdomen that radiated toward the leg. The patient's medical history of interest also included several retroperitoneal collections that were pancreatic in origin and had been treated with percutaneous drains in the last 2 years.

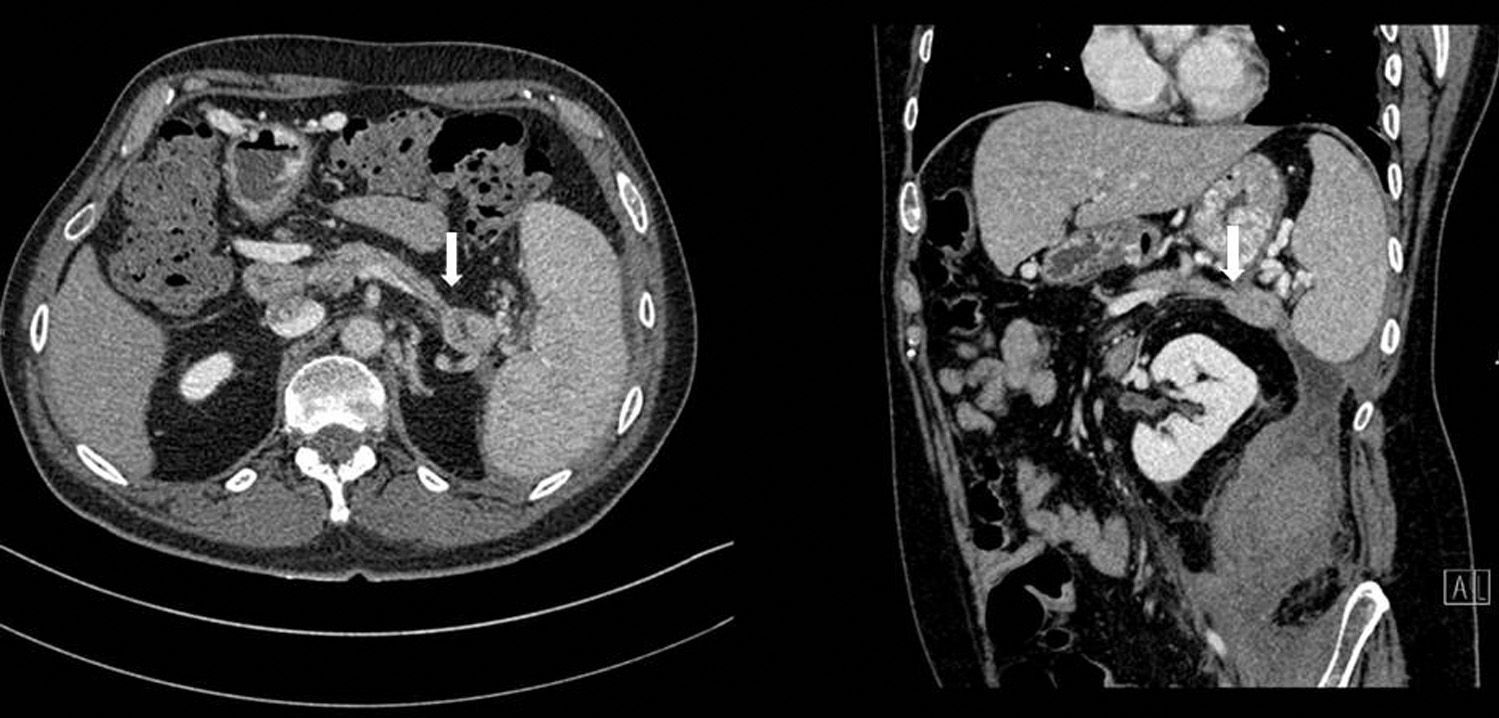

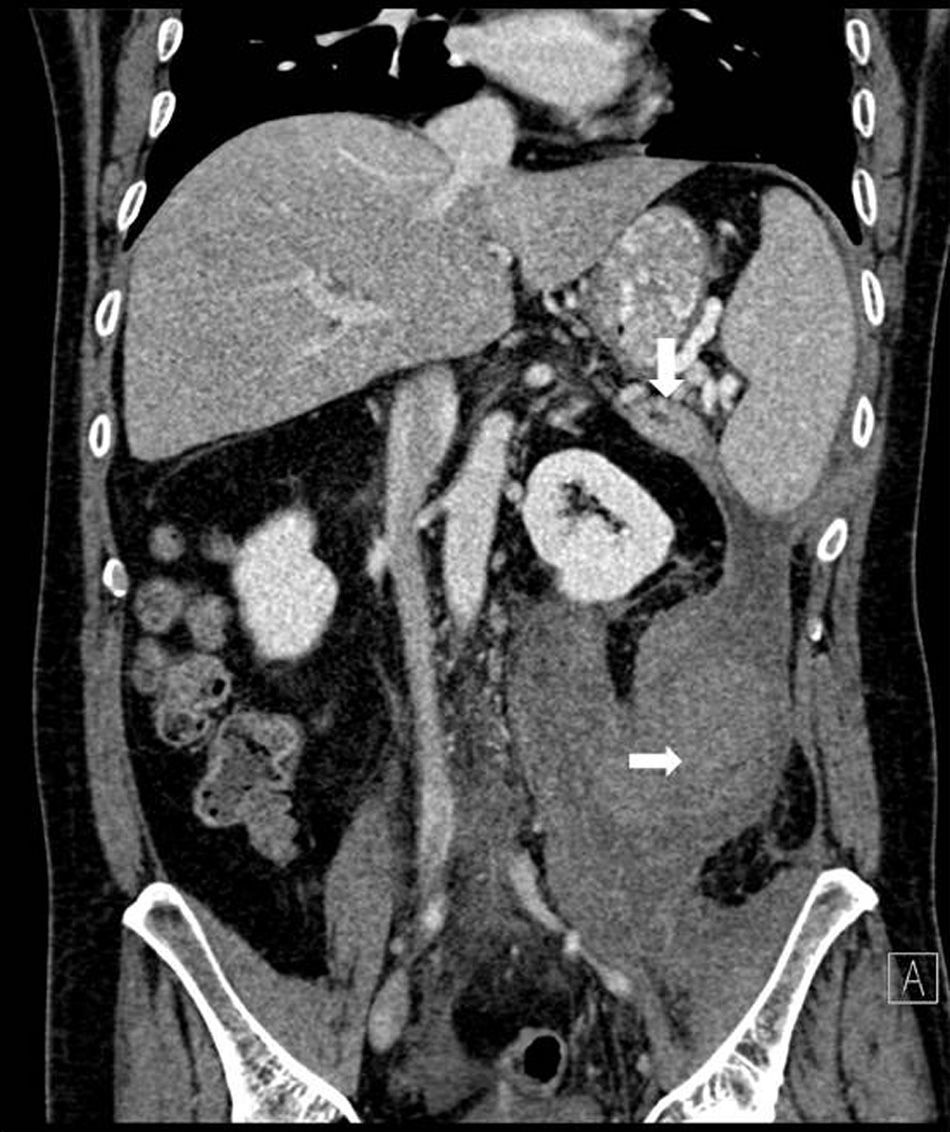

Abdominal CT once again showed a retroperitoneal collection measuring 9.6cm×7cm×20cm, which originated at the tail of the pancreas and extended caudally over the psoas (Fig. 1), displacing the left kidney medially. The pancreas presented diffuse atrophy, with no dilatation of the duct until the distal area of the tail, with an area of 2cm in the tail prior to the dilatation where the duct was not visible (Fig. 2).

Initially, we treated the collection with medical therapy and percutaneous drainage, which only achieved a partial resolution. Afterwards, we considered treatment associated with a pancreatic stent, which was not feasible as the duct was not dilated and disconnected distally. We therefore performed distal splenopancreatectomy and cleaned out the retroperitoneal cavity by means of open surgery. The postoperative period was uneventful and the patient was discharged without incident on the seventh day post-op.

DPDS is a clinical entity where there is a lack of continuity between viable pancreatic tissue and the digestive tract. It involves the appearance of a collection or external pancreatic fistula because the isolated pancreatic segment continues with its exocrine function. There are no clear data about its incidence, although it is estimated that between 10 and 30% of cases of severe pancreatitis develop DPDS.5 Diagnosis is essential and should differentiate (using CT, magnetic resonance imaging and ERCP) DPDS from pancreatic pseudocyst, partial duct disruption, walled-off pancreatic necrosis and other related syndromes. The most frequent location is the neck, especially in pancreatic lithiasis and pancreatic trauma, because this area is only irrigated by the dorsal pancreatic artery, while other regions are supplied by more than one artery. DPDS should be suspected when there is a collection or pancreatic fistula after necrosectomy that is not resolved, although the currently proposed diagnostic criteria are: a collection or necrosis of at least 2cm demonstrated on CT in the pancreatic neck or body with viable distal pancreatic tissue, or a pancreatic duct that enters into the collection at an angle of 90°,6 or when there is extravasation of injected contrast or if there is complete disconnection of the duct in the distal remnant.6 Likewise, it should always be suspected after an external pancreatic fistula or collection has been drained but does not resolve, or in situations with the appearance of recurring pancreatic collections, ascites or pseudoaneurysms7 with associated hemorrhage. Patients with DPDS have a higher probability of diabetes mellitus, metabolic and nutritional problems due to the loss of proteins and electrolytes, and portal hypertension.

Although there are no clearly defined treatment algorithms, it is accepted and recommended by many authors to wait at least 6 weeks after the diagnosis to treat the patient surgically for there to be less inflammation and greater stabilization of the external pancreatic fistula.6,8

Treatment can be endoscopic using ERCP and stent placement or using endoscopic ultrasound-guided internal drainage, but these techniques present less long-term success than surgery, although with lower morbidity and mortality rates. The rate of recurrence is close to 50%, and it is possible to repeat the procedure.8 Furthermore, although surgical resection presents higher morbidity and mortality, it has greater long-term success. Surgical options include resections of the disconnected pancreatic tissue with or without splenectomy and bypass to the small intestine or stomach.7 There are no universally accepted algorithms, but the current tendency is endoscopic treatment and, if that fails or is not possible, resection or surgical bypass.

Authorship/CollaboratorsAll the authors have contributed to the composition of the article, critical review and approval of the final version.

Conflict of InterestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Please cite this article as: Jiménez-Fuertes M, Sánchez Hernández J, Díaz-García G, Ruiz-Tovar J, Durán-Poveda M. Síndrome del ducto pancreático desconectado. Cir Esp. 2016;94:539–541.