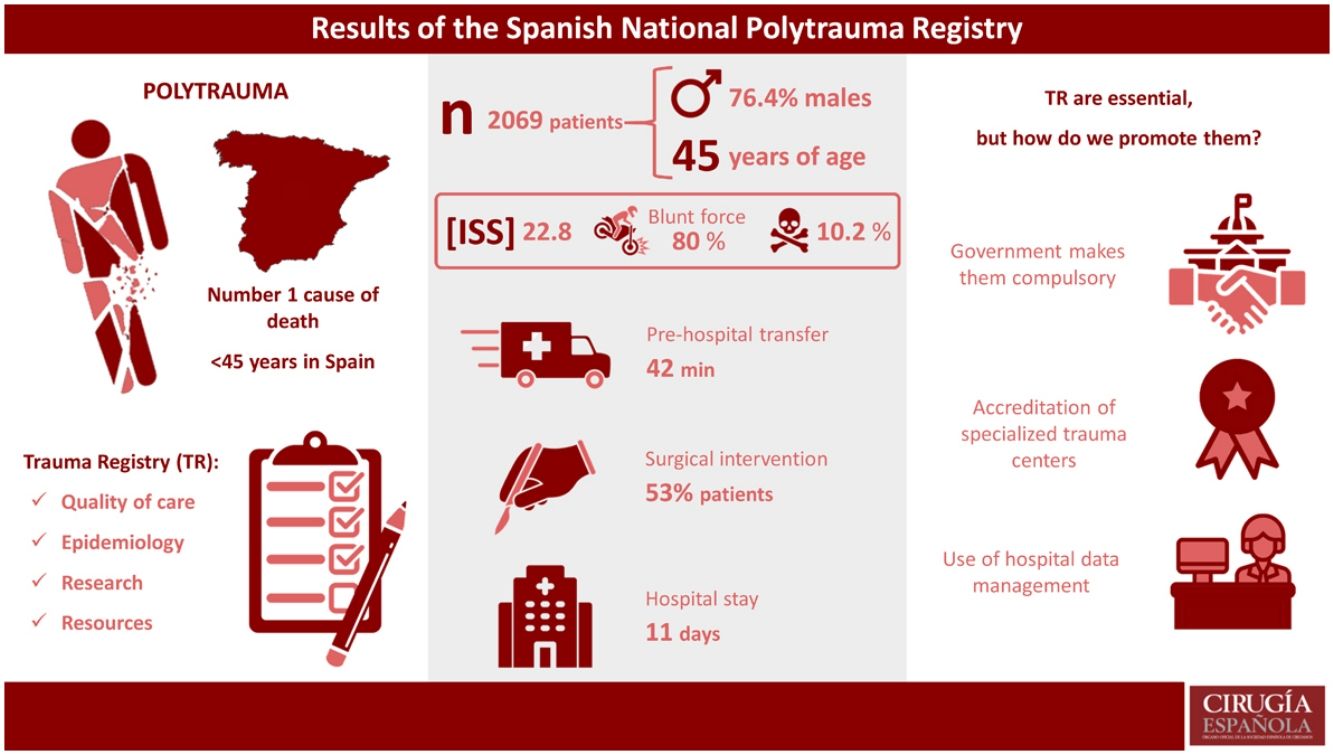

In 2017, the Spanish National Polytrauma Registry (SNPR) was initiated in Spain with the goal to improve the quality of severe trauma management and evaluate the use of resources and treatment strategies. The objective of this study is to present the data obtained with the SNPR since its inception.

MethodsWe conducted an observational study with prospective data collection from the SNPR. The trauma patients included were over 14 years of age, with ISS ≥ 15 or penetrating mechanism of injury, from a total of 17 tertiary hospitals in Spain.

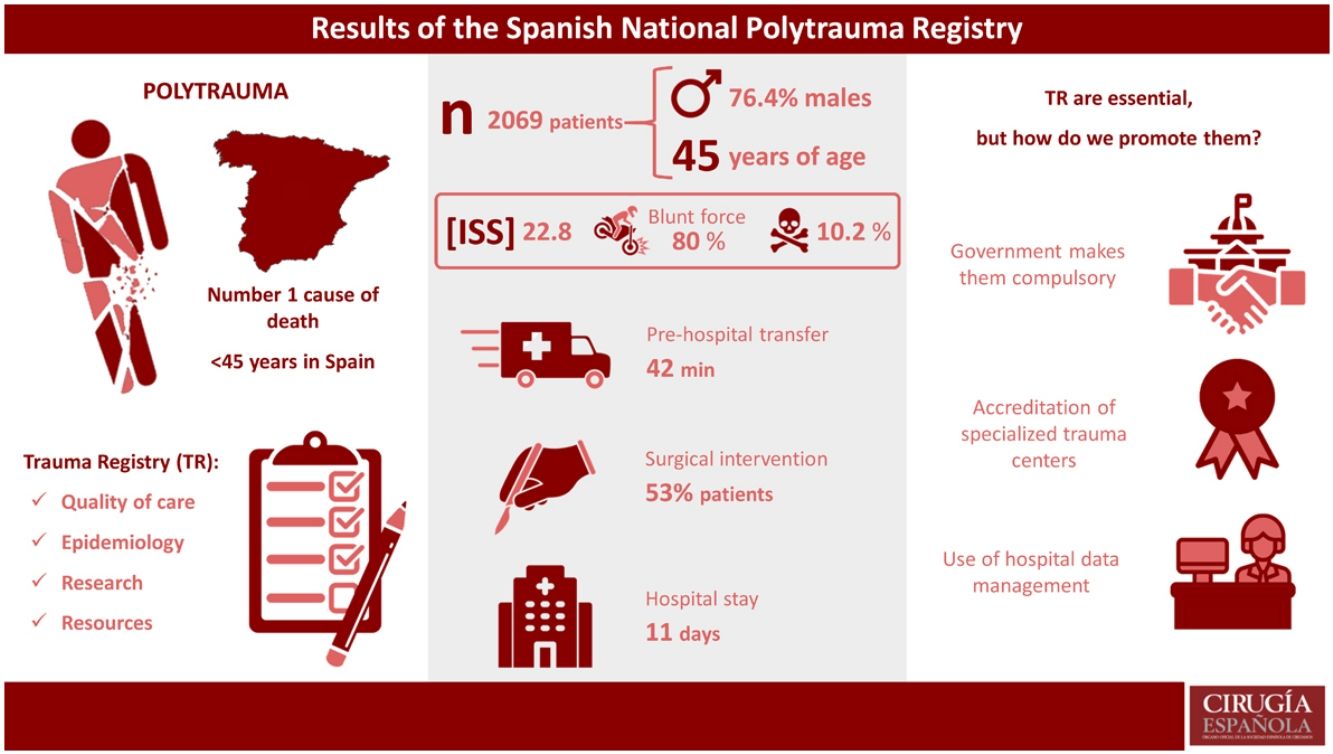

ResultsFrom 1/1/17 to 1/1/22, 2069 trauma patients were registered. The majority were men (76.4%), with a mean age of 45 years, mean ISS 22.8, and mortality 10.2%. The most common mechanism of injury was blunt trauma (80%), the most frequent being motorcycle accident (23%). Penetrating trauma was presented in 12% of patients, stab wounds being the most common (84%).

On hospital arrival, 16% of patients were hemodynamically unstable. The massive transfusion protocol was activated in 14% of patients, and 53% underwent surgery. Median hospital stay was 11 days, while 73.4% of patients required intensive care unit (ICU) admission, with a median ICU stay of 5 days.

ConclusionsTrauma patients registered in the SNPR are predominantly middle-aged males who experience blunt trauma with a high incidence of thoracic injuries. Early addressed detection and treatment of these kind of injuries would probably improve the quality of trauma care in our environment.

En 2017 se emprendió el Registro Nacional de Politraumatismos (RNP) a nivel estatal español, cuya finalidad residía en mejorar la calidad de la atención al paciente politraumatizado grave y evaluar el uso de recursos y estrategias de tratamiento. El objetivo de este trabajo es presentar los datos recogidos en el RNP hasta la actualidad.

MétodosEstudio observacional retrospectivo a partir de los datos recogidos prospectivamente en el RNP. Se incluyen pacientes mayores de 14 años, con ISS ≥ 15 o mecanismo de trauma penetrante, atendidos en 17 hospitales de tercer nivel de España.

ResultadosDel 1/1/17 al 1/1/22 se han registrado un total de 2069 pacientes politraumatizados. El 76.4% son hombres; edad media: 45 años; ISS medio: 22.8 y mortalidad: 10.2%. El mecanismo de lesión más frecuente es el cerrado (80%) con mayor incidencia de accidentes de moto (23%). Un 12% de los pacientes sufren un traumatismo penetrante, por arma blanca en el 84%.

Un 16% de los pacientes ingresa hemodinámicamente inestable en el hospital. Activando el protocolo de transfusión masiva en el 14% de los pacientes e interviniendo quirúrgicamente a un 53%. La estancia hospitalaria mediana es de 11 días. Precisando ingreso en UCI un 73.4% (estancia mediana 5 días).

ConclusionesLos pacientes politraumatizados registrados en el RNP son mayoritariamente varones de mediana edad, que sufren traumatismos cerrados y presentan una elevada incidencia de lesiones torácicas. La detección y tratamiento dirigido de este tipo de lesiones probablemente permitirá mejorar la calidad asistencial del politraumatizado en nuestro medio.

Polytrauma continues to be a major global health problem, causing 4.4 million deaths worldwide each year1. In Spain, polytrauma is one of the main causes of death in the under-45 population2. As a result of the high incidence of polytrauma, the United States promoted the creation of Trauma Centers (TC) in the 1970s as well as specific systems for polytrauma patient care, which were accompanied by the first trauma registries (TR)3–5. Subsequently, thanks to the progressive increase and implementation of specialized centers and organized systems for polytrauma patient treatment worldwide, a decrease has been observed in mortality, hospital stay, diagnostic delay, and healthcare costs linked to multiple trauma injuries6. Thus, the World Health Organization published several recommendations to improve the quality of care for this type of patient in 2009, which included the implementation of TR, among other measures7. TR are an essential tool in polytrauma patient management because they provide epidemiological descriptions, facilitate improved quality of care, help distribute resources efficiently, and support data collection to conduct research projects8.

In Spain, several TR projects have been developed, most of which have been limited to specific regions, such as the GITAN9 project in Andalusia, MTRN10 in Navarra, RETRATO11 in Toledo and TRAUMCAT12 in Catalonia. All of these projects coincide in their regional limitations (by Spanish “autonomous communities”) and the selection of patients with severe polytrauma, following certain criteria. There is only one nation-wide project (RETRAUCI13) that includes polytrauma injury patients treated at various hospitals across the Spanish peninsula, but it exclusively selects patients requiring admission to the intensive care unit.

In order to improve the quality of care for severe multiple trauma patients and evaluate the use of resources and treatment strategies, the Spanish Association of Surgeons (Asociación Española de Cirujanos) launched the Spanish National Polytrauma Registry (SNPR) in 2017, which included multiple trauma patients treated nationwide. The objective of this study is to present the data collected with the SNPR to date.

MethodsWe have conducted a retrospective observational study based on data collected prospectively in the Spanish National Polytrauma Registry14 from January 2017 to January 2022. This is a prospective, multicenter registry that includes multiple trauma patients over the age of 14, with ISS ≥ 15 and/or penetrating trauma, treated at 17 tertiary level hospitals in Spain (Supplemental material 1). The study was developed using STROBE guidelines for reporting observational studies15 (Supplemental material 2). All patients were prospectively registered in an online database while always complying with Spanish data protection legislation. Recorded variables include: epidemiological data (sex and age), trauma (blunt/penetrating), severity criteria (Revised Trauma Score [RTS], Injury Severity Score [ISS], New Injury Severity Score [NISS]), prehospital and hospital vital signs (heart rate, respiratory rate, systolic blood pressure, and Glasgow scale), complementary examinations performed, injuries diagnosed, treatment received (activation of the massive transfusion protocol, blood products administered, embolization, surgical intervention), hospital stay, and mortality.

Statistical analysisThe statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS® v25 program (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA). The normal distribution of the variables was analyzed using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. The descriptive analysis of the quantitative data was carried out according to measures of central tendency (mean, median) and dispersion (standard deviation and interquartile range), while the qualitative data were analyzed by percentages. For the analysis of the differences between ISS, the normality of the variable was assumed, and the Student’s t test was applied.

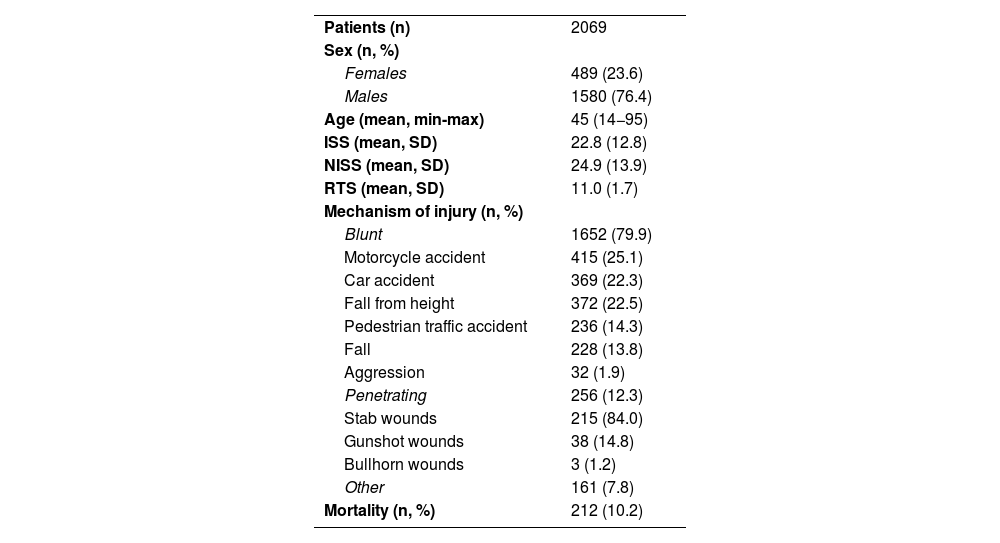

ResultsFrom January 2017 to January 2022, a total of 2069 multiple trauma patients were registered. Table 1 shows the demographic data of the analyzed sample, where 76.4% of men stand out (n = 1580/2069), with a mean age of 45 years (SD 18.7), mean ISS of 22.8 (SD 12.8) and mortality of 10.2% (n = 212/2069). The most frequent mechanism of injury was blunt trauma (79.9%, n = 1652/2069), and motorcycle accidents were the most frequent cause (25.1%, n = 415/1652), followed by car accidents (22.3%, n = 369/1652) and fall from height (22.5%, n = 372/1652). Penetrating trauma injuries affected 12.3% (n = 256/2069) of the patients, and the most frequent injury was stabbing (84%, n = 215/256).

Demographic data.

| Patients (n) | 2069 |

| Sex (n, %) | |

| Females | 489 (23.6) |

| Males | 1580 (76.4) |

| Age (mean, min-max) | 45 (14−95) |

| ISS (mean, SD) | 22.8 (12.8) |

| NISS (mean, SD) | 24.9 (13.9) |

| RTS (mean, SD) | 11.0 (1.7) |

| Mechanism of injury (n, %) | |

| Blunt | 1652 (79.9) |

| Motorcycle accident | 415 (25.1) |

| Car accident | 369 (22.3) |

| Fall from height | 372 (22.5) |

| Pedestrian traffic accident | 236 (14.3) |

| Fall | 228 (13.8) |

| Aggression | 32 (1.9) |

| Penetrating | 256 (12.3) |

| Stab wounds | 215 (84.0) |

| Gunshot wounds | 38 (14.8) |

| Bullhorn wounds | 3 (1.2) |

| Other | 161 (7.8) |

| Mortality (n, %) | 212 (10.2) |

n: number of patients; SD: standard deviation; ISS: Injury Severity Score; NISS: New Injury Severity Score; RTS: Revised Trauma Score.

The median prehospital care time was 42 min (minimum 1 min and maximum 360 min) from the activation of the ambulance until arrival at the hospital. Some 15% of the patients (n = 310/2069) were hemodynamically unstable in prehospital care, requiring prehospital orotracheal intubation in 23.4% (n = 484/2069). A total of 248 patients presented a Glasgow Coma Score ≤8 upon arrival of the ambulance, 95% of whom were intubated prehospital. Median prehospital serum therapy was 500 mL (min 0 mL and max 4500 mL).

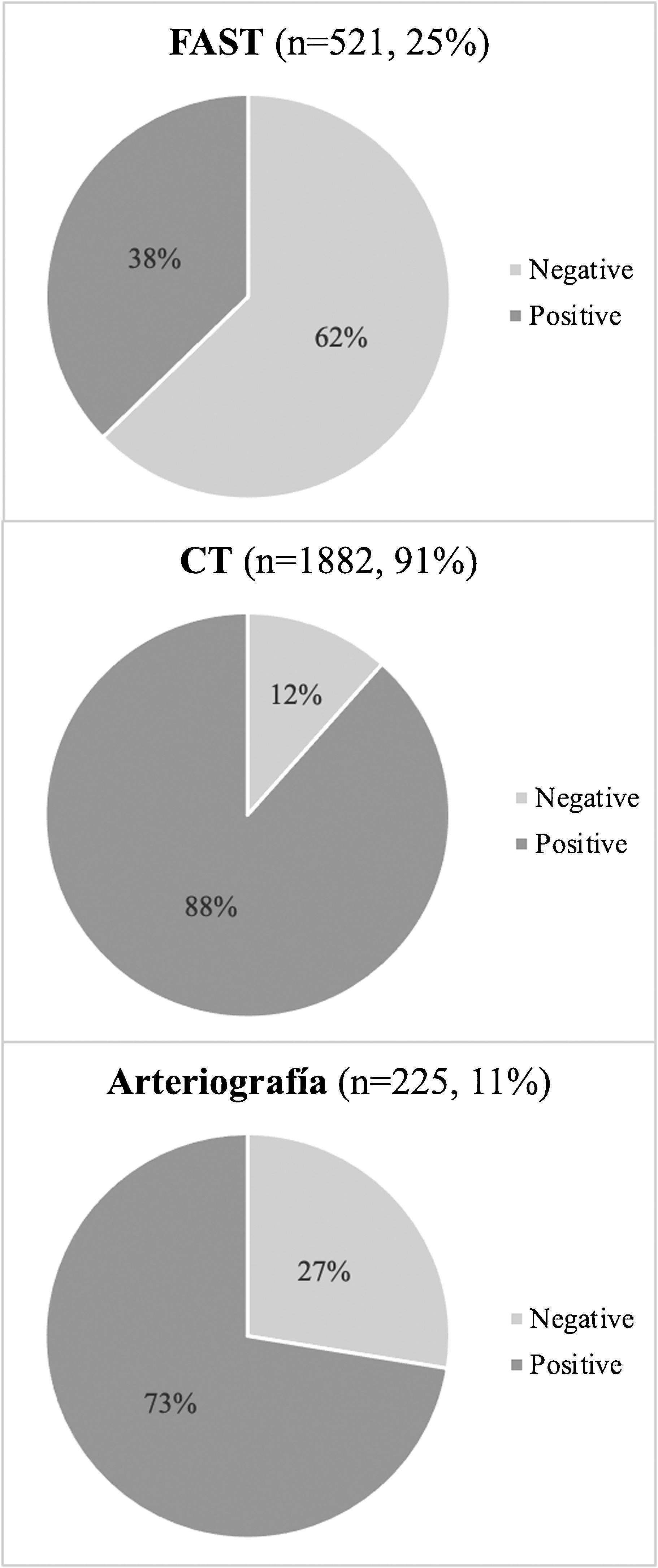

In hospital, 16% (n = 331/2069) of the patients were hemodynamically unstable upon arrival. Meanwhile, 20.6% of patients presented a prehospital Shock Index ≥ 1, which reached 22.6% at the hospital. The diagnostic tests performed are shown in Fig. 1. Focused assessment with sonography for trauma (FAST) was performed on 521 patients, which was positive in 38% of the cases (n = 198/521) and after which exploratory laparotomy was performed in 73% (n = 144/198). Arteriography was performed in 225 patients, and 73% of cases required embolization (n = 164/225).

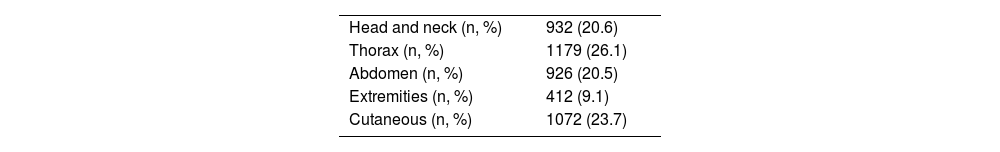

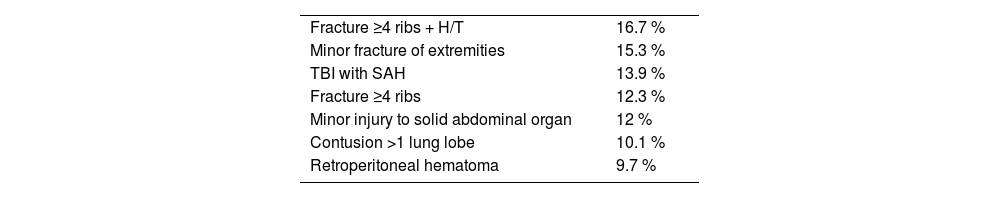

Table 2 describes the lesions according to the affected region, demonstrating a higher incidence of thoracic lesions (26.1%), followed by skin lesions (23.7%) and traumatic brain injury (26.1%). Table 3 shows the most frequently described injuries: firstly, fractures of 4 or more ribs associated with hemo/pneumothorax (16.7%); secondly, minor fractures of the extremities (15.3%); and thirdly, traumatic brain injury with subarachnoid hemorrhage (13.9%).

Most frequent lesions.

| Fracture ≥4 ribs + H/T | 16.7 % |

| Minor fracture of extremities | 15.3 % |

| TBI with SAH | 13.9 % |

| Fracture ≥4 ribs | 12.3 % |

| Minor injury to solid abdominal organ | 12 % |

| Contusion >1 lung lobe | 10.1 % |

| Retroperitoneal hematoma | 9.7 % |

H/T: hemothorax/pneumothorax; TBI: traumatic brain injury; SAH: subarachnoid hemorrhage.

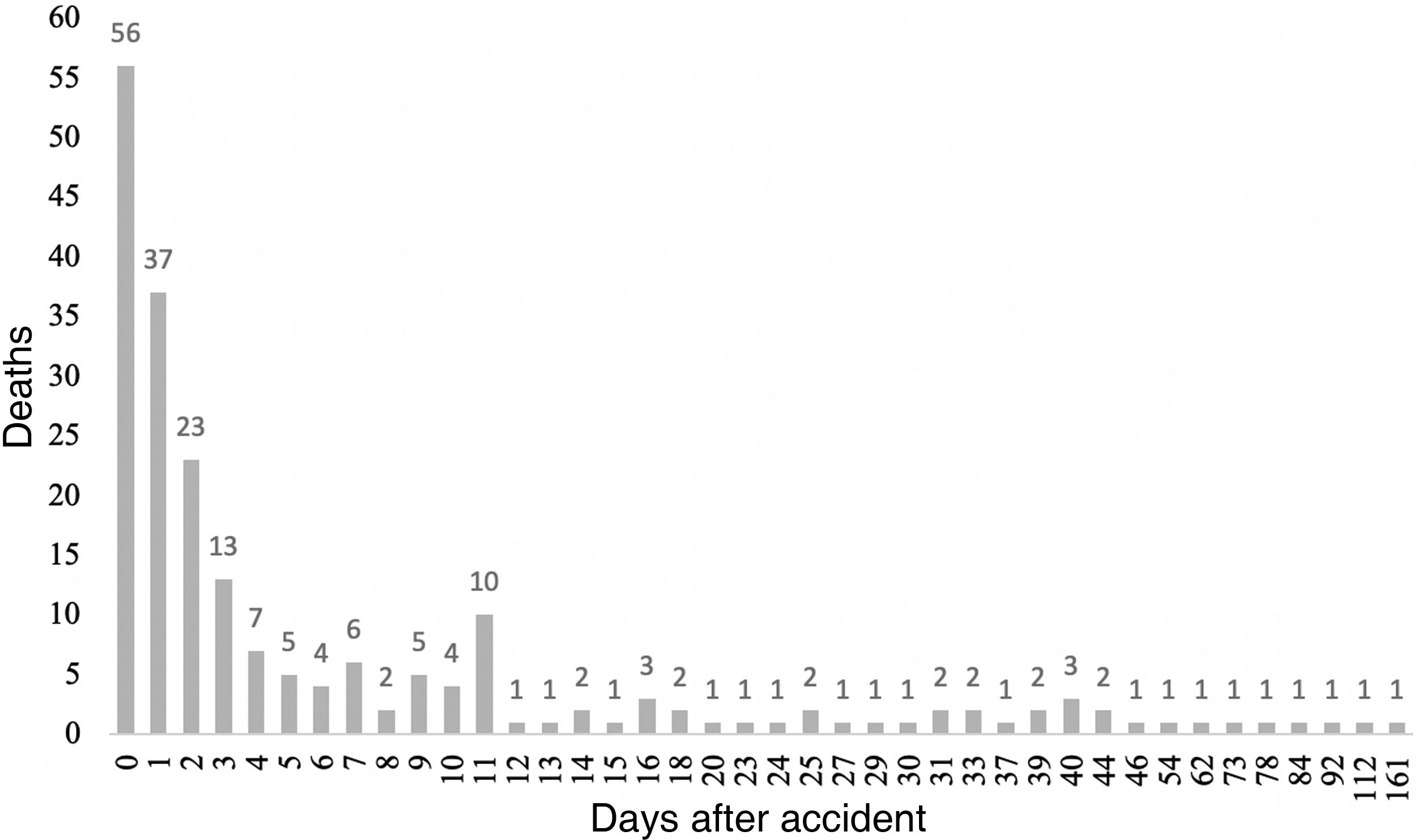

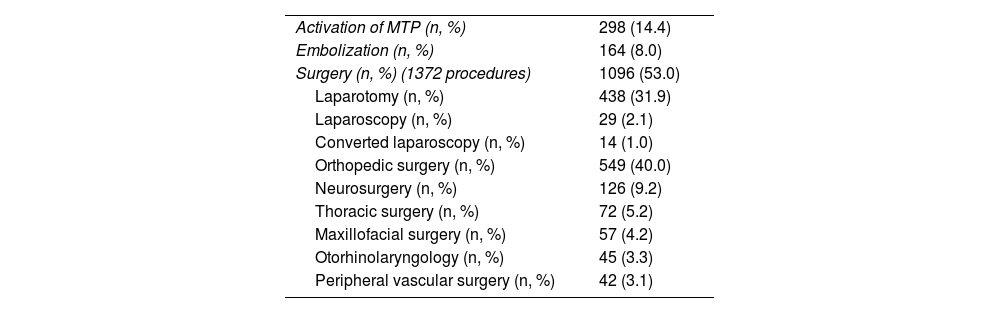

Table 4 shows the treatments carried out. The massive transfusion protocol was activated in 14.4% of the patients (n = 298/1840), 88% of which had a Shock Index ≥0.8 (262/289). More than 10 packed red blood cell units were transfused in 14.6% of patients (82/289). Surgery was required in 53% of the patients (n = 1096/2069). The most frequently performed surgery was laparotomy in 31.9% of patients (n = 438/1096), while 26.5% (n = 116/438) required damage-control surgery. In these patients, temporary abdominal closure was indicated for a median of 2 days (minimum 0 days and maximum 28 days); in 7 patients (6%; 7/116), definitive abdominal closure was performed starting 7 days after the accident. Fig. 2 shows the distribution of patient mortality during the hospital stay, which shows a predominance in the first days of hospitalization. Supplemental material 3 demonstrates the correlation between mortality and ISS values, confirming higher mortality at higher ISS (P < .001).

Treatments performed.

| Activation of MTP (n, %) | 298 (14.4) |

| Embolization (n, %) | 164 (8.0) |

| Surgery (n, %) (1372 procedures) | 1096 (53.0) |

| Laparotomy (n, %) | 438 (31.9) |

| Laparoscopy (n, %) | 29 (2.1) |

| Converted laparoscopy (n, %) | 14 (1.0) |

| Orthopedic surgery (n, %) | 549 (40.0) |

| Neurosurgery (n, %) | 126 (9.2) |

| Thoracic surgery (n, %) | 72 (5.2) |

| Maxillofacial surgery (n, %) | 57 (4.2) |

| Otorhinolaryngology (n, %) | 45 (3.3) |

| Peripheral vascular surgery (n, %) | 42 (3.1) |

MTP: massive transfusion protocol; n: number of patients.

Median hospital stay was 11 days (range: 0–281 days), and 72.5% of patients (n = 1499/2069) required admission to the ICU with a median stay of 5 days (range: 0–180 days).

DiscussionTR are necessary to improve the care of polytraumatized patients because they enable us to monitor the results obtained, detect targets for on intervention, etc.3,6–8,16,17. This paper describes the characteristics of multiple trauma patients treated between 2017 and 2022 at 17 Spanish hospitals registered in the Spanish National Polytrauma Registry.

While there are several indicators of quality of care in polytraumatized patients, hospital mortality is the only universally accepted indicator and is the most widely used in published registries3,7,8. The mortality rate in this series (10.2%) is higher than the rates described by the US National Trauma Databank (NTDB) of 4.4%18 or the English Trauma Audit Research Network (TARN) of 7.8%19. However, both the NTDB and TARN include all polytraumatized patients treated in all American or English TC, respectively, with an ISS greater than 15 in 22% of the American sample and in 32% of the English sample. This is far different from the Spanish registry, where 64% of the patients present an ISS greater than 15; therefore, the data are probably not comparable between these registries. In contrast, registries from countries with samples similar to ours, with a high incidence of blunt trauma and high mean ISS, show similar mortality values in their registries. For example: the French registry describes mortality of 9.6%, with 48% of patients having ISS greater than 1520; in the Australian registry, whose sample has 70% of patients with ISS over 15, mortality is 14.7%3. Therefore, in order to make comparisons between different registries, it is necessary to take into account the inclusion criteria of each registry and the type of patients they describe, since Supplemental material 3 demonstrates that the higher the ISS, the higher the mortality. At the same time, TR make it possible to identify goals to improve care and help reduce the mortality of polytrauma patients. This was demonstrated by Cameron et al., who described a decrease in mortality from 14.7% to 12.7% after a TR was implemented in Australia, thanks to the identification of areas for improvement and the promotion of prevention policies3.

In 1982, Trunkey described the trimodal distribution of death as a consequence of injury, which consisted of three periods or peaks21; however, after the publications by Demetriades in 2005 and Gunst in 2010, it is currently thought that mortality after trauma injury has a bimodal distribution22,23. This modification is due to the disappearance of the third peak, which is attributed to the development of standardized training for physicians, improved prehospital care, and the development of trauma centers with well-established groups and protocols for multiple trauma patient care. Coinciding with the previously described results, the population of our study presents a bimodal distribution of mortality, as can be observed in Fig. 2.

Additionally, there are other indicators, such as the incidence of preventable deaths3,16, hospital stay8, adverse effects8, time elapsed from the patient’s arrival to the hospital until surgery or complementary tests3, and quality of life after hospital discharge19. These quality indicators must be considered when designing a TR, since they can be established as objectives for improving standardized treatment of multiple trauma patients. Currently, the SNPR only includes hospital stay and ICU stay; however, in future modifications and updates to the SNPR, the rest of the indicators described will also be taken into consideration.

It is complicated to analyze the performance of prehospital care when using TR that collect data predominantly from hospitals, as there is potentially a significant loss of prehospital information that implies a non-negligible bias. Even so, we can evaluate the prehospital transfer times and compare them with those of other countries. Classically, 2 prehospital care strategies have been described: “scoop and run”, and “stay and play”. In most European countries, patients receive prehospital care by medical professionals who insert an IV catheter and initiate the administration of fluid therapy, analgesia, sedation and vasoactive drugs, and perform orotracheal intubation or chest compression maneuvers, if necessary20. A true “scoop and run” has only been described in 3 cities in the United States: Philadelphia, Sacramento, and Detroit24, where patients with penetrating trauma can be transported by police straight to the hospital. Studies comparing police transfer with ambulance transfer report similar risk-adjusted mortality in both groups, concluding that police transport is no worse than transfer in conventional ambulances24,25. Nevertheless, the studies making such comparisons always select groups of patients with penetrating trauma, so these conclusions would be difficult to apply in our population, where most injuries are blunt-force trauma whose management differs considerably from penetrating trauma. Generally, the times described in the literature are <10 min for direct transfer and 20−73 min for ambulance transfer20,24,25, which indicates that the times in our study are similar to those of other countries. The study by Gauss et al. in France, which can be extrapolated to our population, showed that longer prehospital care times correlated with greater hospital mortality of patients20. Gauss concluded that shorter transfer times should be an objective for improvement, while always maintaining minimum standards for interventions necessary to meet the critical needs of patients. A balance between “scoop and run” and “stay and play” is probably the best option for prehospital care, which should be determined by the mechanism of injury, distance to the hospital and resources available5.

The main limitation of this study is also common of other studies based on TR, since the participation of hospitals is voluntary, and sometimes the sample obtained may not be truly representative of the population we analyzed. One way to avoid such a bias would be to link this type of registry to a government quality-control program, so that hospitals do not obtain their certification as official trauma centers without clear objectives and optimal results in polytrauma care, similar to the United States8,16,18. In doing this, it would be highly recommended to be able to designate hospital data managers, since the responsibility of data collection often falls onto shoulders of healthcare professionals who care for these patients, overloading their care activity and making it difficult to collect quality data.

In conclusion, patients with polytrauma registered in the SNPR are mostly males under the age of 45, who suffer blunt trauma and present a high incidence of thoracic injuries. Healthcare measures aimed at correctly detecting and treating this type of injury can help improve the quality of care for polytrauma patients and reduce their mortality. For this, it is necessary to maintain the collection of data at the state level and promote studies to define targets for improving the management of these patients.

Sources of fundingNone of the authors present any conflicts of interest, nor have they received any funding from any entity.

We would like to thank all the medical professionals who have participated in the data collection process as well as the RNP Collaboration Group: Salvador Navarro-Soto, Hospital Universitari Parc Taulí, Sabadell; Felipe Pareja-Ciuró, Hospital Universitario Virgen del Rocío, Sevilla; Virginia Durán-Muñoz-Cruzado, Hospital Universitario Virgen del Rocío, Sevilla; Pedro Yuste-García, Hospital 12 de Octubre, Madrid; José Lopez-Ruiz, Hospital Universitario Virgen de Macarena, Sevilla; Judit Parra-Chiclano, Hospital General Universitario de Alicante, Alicante; Gonzalo Tamayo, Hospital de Cruces, Barakaldo; Aitor Landaluce-Olavarria, Hospital de Galdakao, Galdakao; Bakarne Ugarte-Sierra, Hospital de Galdakao, Galdakao; Andrea Craus, Hospital Universitari Son Espases, Palma; Anai Oseira, Hospital Universitari Son Espases, Palma; Ignacio Rey-Simó, Complejo Hospitalario Universitario A Coruña, A Coruña; Alex Forero, Hospital Universitario La Paz, Madrid; Jenn Guevara, Hospital Universitario La Paz, Madrid; Jose María Jover-Navalón, Hospital Universitario de Getafe, Getafe; Eduardo Lobo, Hospital Ramón y Cajal, Madrid.