Defects in consolidation are one of the local complications of bone fractures. The most common causes are excess motility of the fractured area and poor irrigation. Clinton and Mark1 report the presence of delayed consolidation and pseudarthrosis in 5%–10% of fractures, and the most common locations are the femur and tibia.

Sternal pseudarthrosis is an uncommon entity, and most cases reported in the literature are longitudinal pseudarthrosis secondary to midline sternotomies.2

We present the first case of sternal pseudarthrosis as a consequence of a transverse sternal fracture after blunt chest trauma reported in the Spanish literature.

Case ReportA 36-year-old man came to the outpatient clinic of the Department of Thoracic surgery with central chest pain of 2 years duration. He needed daily analgesia with NSAIDS, and referred instability and a clicking sound in the upper third of the sternum. He had a prior history of a transverse sternal fracture after blunt chest trauma while playing rugby that was managed conservatively. On physical examination no apparent defects were found, except clicking of the sternum when anterior flexion of the trunk was performed.

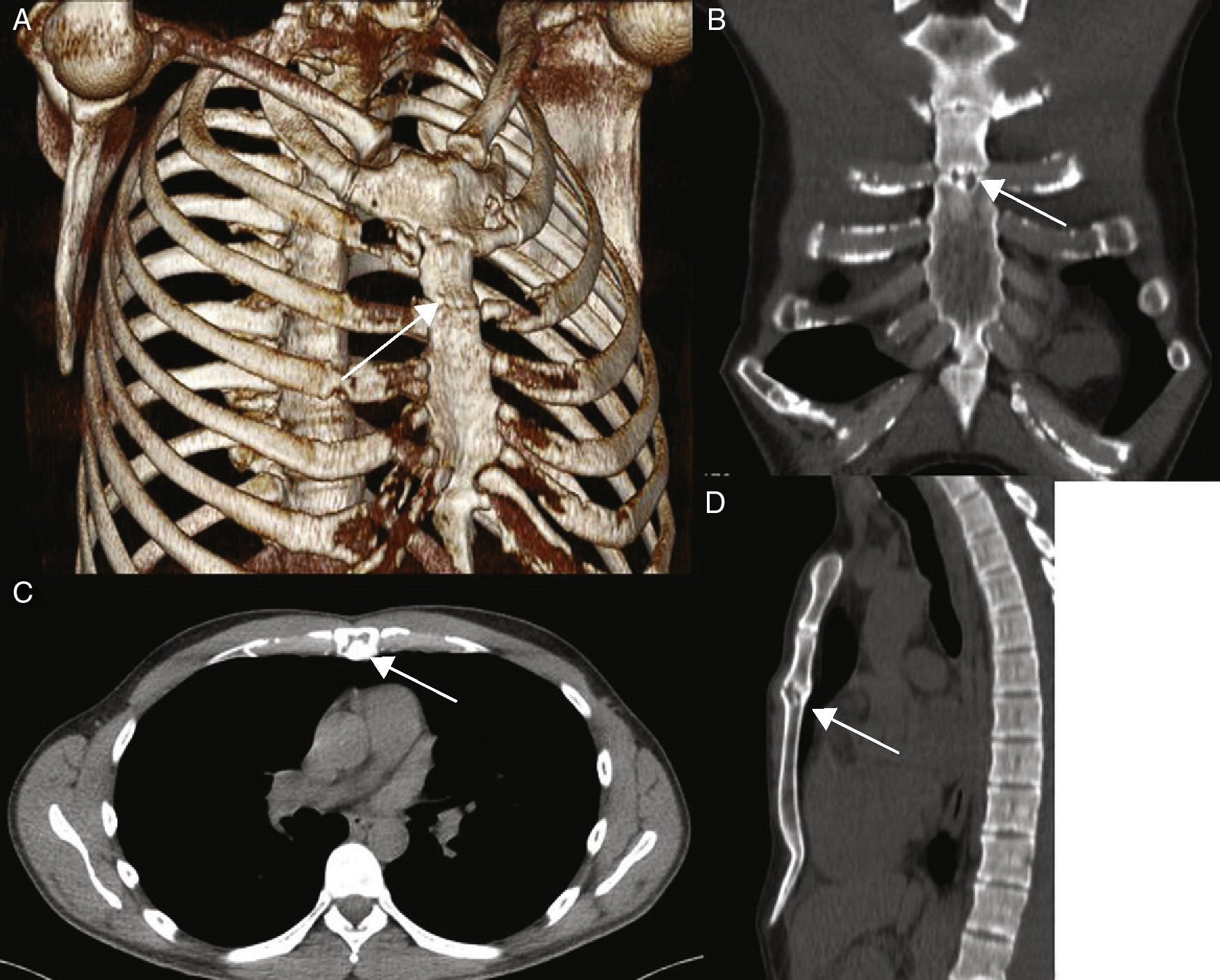

A chest CT scan with bone reconstruction confirmed the suspicion of sternal pseudarthrosis at the level of the joining of the third rib (Fig. 1).

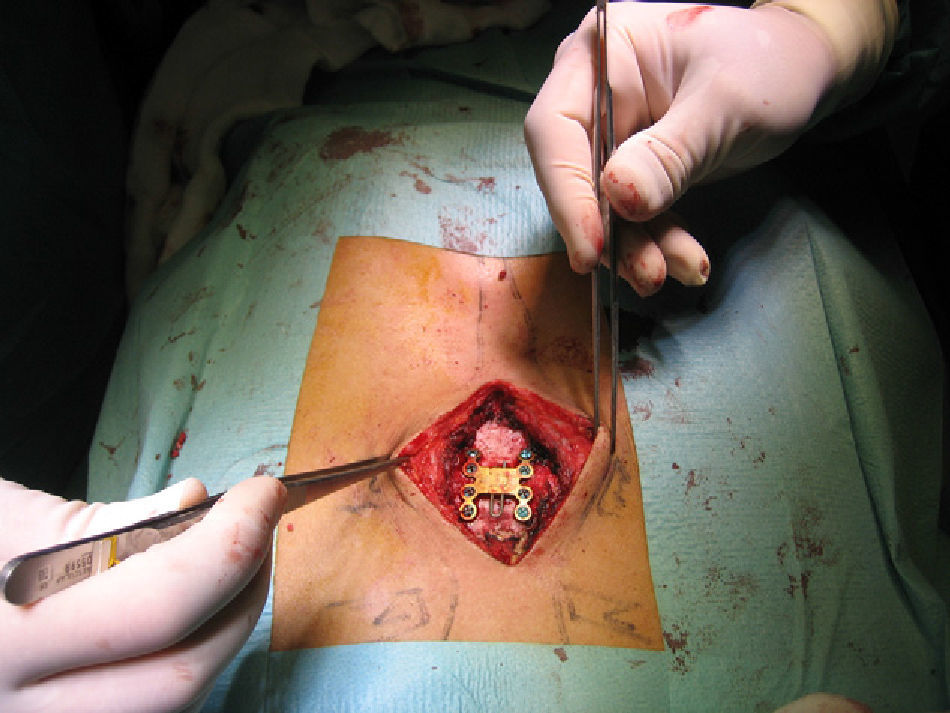

Surgery: under general anaesthesia the sternum was exposed using a midline incision and separation of the pectoral muscles. A subperiosteal dissection was performed from the midline to the sternal edges. The edges of the pseudarthrosis were debrided and titanium osteosynthesis material was placed (Titanium Sternal Fixation System, Synthes, USA) (Fig. 2).

The patient had an uneventful recovery and one month after surgery he remains asymptomatic, with no clicking and the instability has disappeared.

DiscussionSternal fractures represent approximately 8% of admissions due to chest trauma,3 and are more frequent due to the increase in seatbelt use. Traditional management of these lesions is observation, cardiac monitoring and analgesia. The most common associated complications are rib fractures, vertebral injury and cardiac contusion.3

Late complications related to consolidation of the sternal fracture are rare, and there are few references in their physiopathology.4 Pseudarthrosis generally affects long bones, specially in the lower extremities and is associated with the following risk factors1,2: The presence of systemic diseases (diabetes, tuberculosis, hypothyroidism, decalcifying osteopathy, etc.), smoking, steroids, factors related to the location and type of fracture (diaphysis and middle third fractures have a higher risk), lack of adequate immobilization and errors in fracture reduction without proper contact of the edges.

Pseudarthrosis can be classified into two large groups1: (1) atrophic, which present a loss of intermediate fragments and substitution with scar tissue, related to poor vascularization and (2) hypertrophic, which are a consequence of a mechanical problem, such as excess mobilization. In colloquial terms, these last types are called “elephant's foot” because of their radiological presentation, with an increase in bony fragments that appear at the edges of the callous. There are very few descriptions in the literature of sternal pseudarthrosis caused by chest trauma; therefore, to choose a corrective treatment, one must look at series of patients with sternal pseudarthrosis or non-union after midline sternotomies.5–7 Conservative treatment with teriparatide,8 ultrasounds2 or growth factors (bone morphogenetic proteins),9 has been used, although the most accepted treatment is fixation with osteosynthesis material.5,6,10 Several groups associate bone grafts6 or bone morphogenetic proteins4 to favour formation of new consolidation.

We consider that posttraumatic sternal pseudarthrosis can be treated by correction of the cause and favouring the ossifying process, and we recommend an osteosynthesis with titanium material after debridement of the fracture edges.

Please cite this article as: Zabaleta J, Aguinagalde B, Fuentes MG, Bazterargui N, Izquierdo JM. El jugador de rugby con una «pata de elefante» en el pecho. Cir Esp. 2013;91:342–344.