Focal nodular hyperplasia (FNH) is the second most common benign liver lesion after hemangioma. It represents 8% of all benign liver lesions and is more common in women between the ages of 30 and 50. Its diagnosis is usually incidental during testing for other pathologies.1

Conservative treatment has been well established in the cases of asymptomatic lesions due to their low risk of hemorrhage or malignant degeneration.

Lesions larger than 4cm may cause abdominal pain by compressing neighboring organs, hemorrhage or distension of Glisson's capsule. Surgery could therefore be indicated,2 but the surgical risk may be greater than any potential benefits. Transarterial embolization (TAE) of these lesions can be considered a less invasive, less risky alternative to surgical treatment.3

We present two cases where TAE has been effective in the treatment of abdominal pain caused by hepatic FNH.

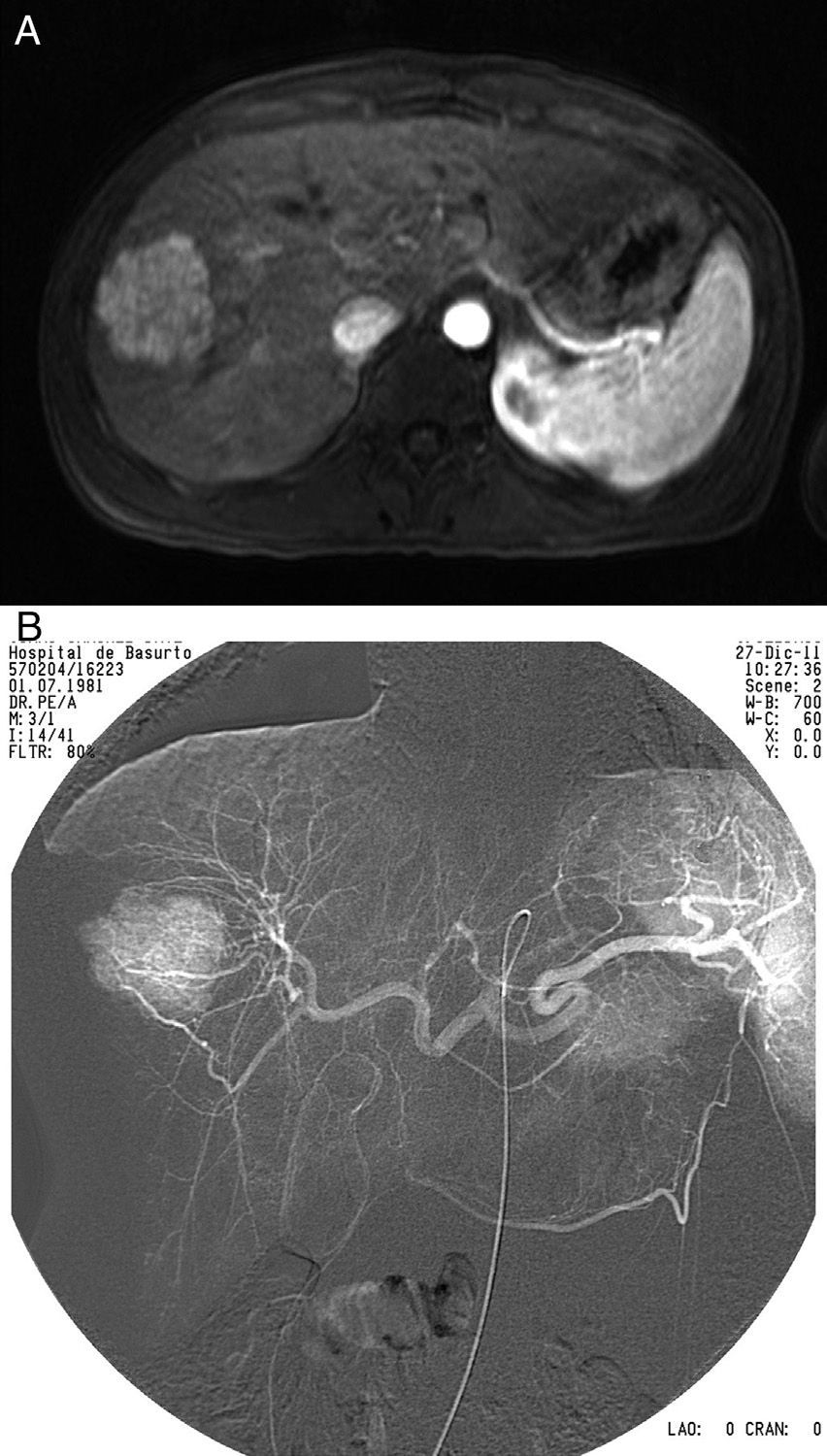

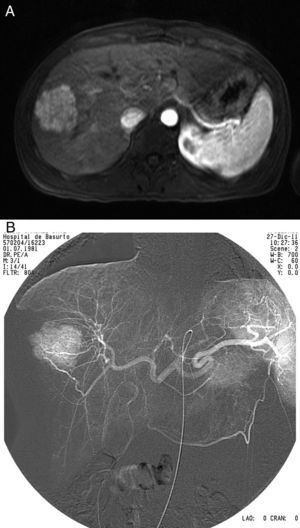

Case 1The patient was a 31-year-old woman who had been taking oral contraception for the previous 10 years and presented with multiple episodes of abdominal pain that limited her daily activities. A radiology study discovered a space-occupying lesion (SOL) in segment viiimeasuring 4.8cm×4.1cm (Fig. 1A) compatible with FNH. Work-up and tumor marker levels were normal.

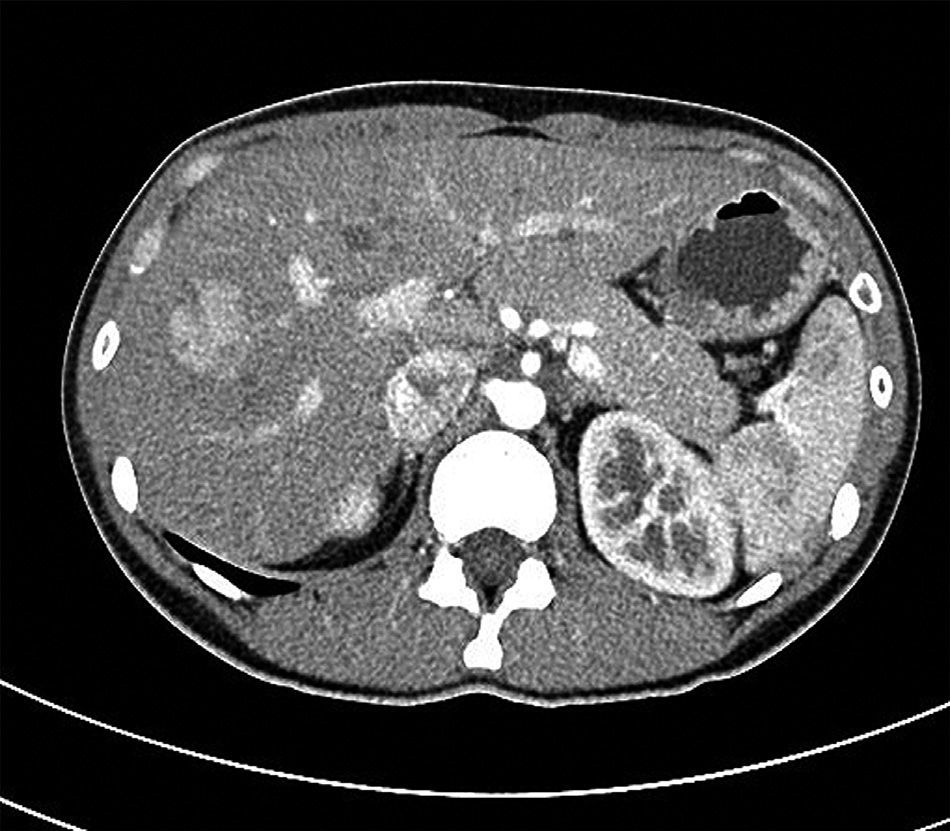

After failed pain management treatment and psychiatric pathologies had been ruled out, the patient was re-evaluated. We decided to perform TAE (Fig. 1B), which provided optimal results. Three months later, the patient continued to be asymptomatic and CT reported a partially necrotized SOL measuring 3cm (Fig. 2).

Case 2The patient was a 35-year-old woman who had taken oral contraception for 5 years. She complained of abdominal pain that had been developing over several months and caused repeated visits to the emergency room. Radiological tests showed a SOL in segment vi measuring 5.8cm×3.6cm that was compatible with FNH.

During follow-up, progressive growth of the lesion was observed, which grew to 6.8cm×6.8cm, with persistent pain despite treatment with analgesia.

TAE has been able to completely control the pain to date, in spite of the maintained lesion size in successive follow-up control tests.

The origin of FNH can be a hyperplastic response of the hepatocytes to arterial injury or hyperperfusion or a preexisting vascular malformation.1

Pathologically, the lesions are usually solitary, with a size between 3 and 5cm. The macroscopic appearance is that of a firm tumor formation, with a color similar to the surrounding liver parenchyma and a hypervascularized surface. When sectioned, they typically present a central scar of connective tissue with surrounding nodules of liver tissue and pseudocapsule. These nodules have no portal triad but have normal hepatocytes with proliferation of twisted blood vessels and bile ducts.

Different types of FNH have been described depending on whether there is predominating nodular architecture or vascular malformation. The growth of these lesions is proportional to the sequestered blood supply.

Clinically, FNH are asymptomatic in 80%–90% of cases, which are generally incidental findings. Symptoms are characterized by abdominal pain of varying intensity, depending on the size and situation of the lesion. Complications such as necrosis or hemorrhage are usually exceptional, and there are no data of malignant degeneration.

CT and MRI with gadolinium are the best diagnostic methods. FNH are homogeneously iso- or hypointense in T1 and hyperintense in T2, with a very hyperintense scar later in T2 in 50%–70% of cases. The specificity of MRI for FNH is 98%.

The benign behavior of these lesions makes conservative treatment and follow-up the appropriate medical course of action. In cases of intense pain, progressive growth or risk of rupture, more aggressive treatment could be indicated.2 Surgical resection in these patients should be carefully assessed since there is a significant mortality rate, which should be taken into account when treating benign processes in young patients.

It is in these cases where less aggressive procedures like TAE should be considered as an alternative treatment, with resolution of the symptoms regardless of the minimal, partial or complete reduction of the size of the lesion.4–6 Although the limited data published do not exactly clarify the indications of the therapeutic method, age, persistent pain after long periods of conservative treatment, as well as the exclusion of other possible causes have been our inclusion criteria.

TAE is not free of complications, such as post-embolization syndrome (pain, nausea, vomiting, fever, leukocytosis, etc.) or other more serious complications, including necrosis of the embolized tissue and abscessification, pneumonia, pleural effusion or renal failure if the embolized mass is large and there is a massive discharge of toxic radicals.

Our two patients who underwent TAE presented none of these complications, and the pain completely disappeared in a very short period of time, even when it was not accompanied by a parallel radiological reduction.

Although the short follow-up time and the small number of patients treated do not enable us to draw definitive conclusions, we believe that transarterial embolization can be considered an alternative treatment to surgery in the cases of symptomatic focal nodular hyperplasia.

Please cite this article as: Gómez García MP, Cruz González I, Peña Baranda B, Atín del Campo VM, Méndez Martín JJ. Embolización arterial como tratamiento de la hiperplasia nodular focal sintomática. Cir Esp. 2014;92:135–137.