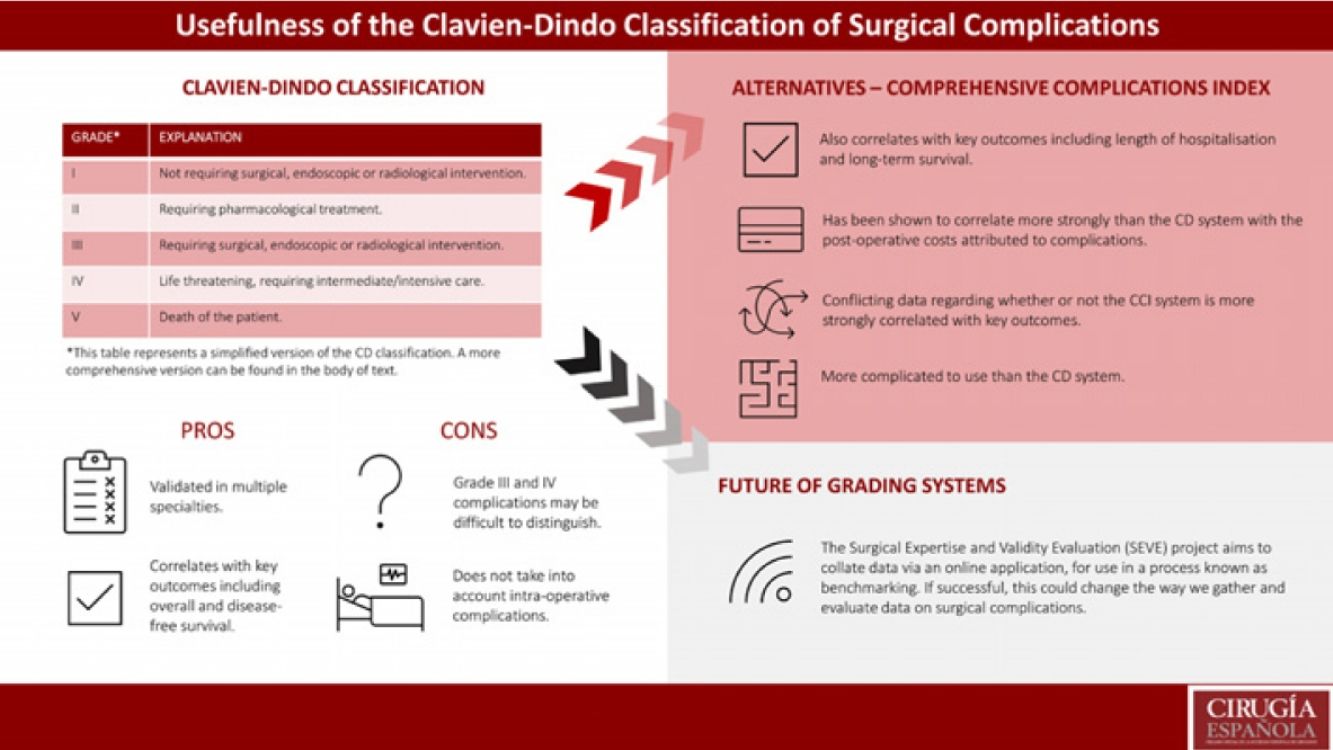

The Clavien-Dindo (CD) classification is widely used in the reporting of surgical complications in scientific literature. It groups complications based on the level of intervention required to resolve them, and benefits from simplicity and ease of use, both of which contribute its to high inter-rater reliability. It has been validated for use in many specialties due to strong correlation with key outcome measures including length of stay, postsurgical quality of life and case-related renumeration. Limitations of the classification include concerns over differentiating grade III and IV complications and not classifying intraoperative complications. The Comprehensive Complication Index is an adaptation of the CD classification which generates a morbidity score from 0 to 100. It has been proposed as a more effective method of assessing the morbidity burden of surgical procedures. However, it remains less popular as calculations of morbidity are complicated and time-consuming. In recent years there have been suggestions of adaptations to the CD classification such as the Clavien-Dindo-Sink classification, while in some specialties, completely new classifications have been proposed due to evidence the CD classification is not reliable. Similarly, the Surgical Expertise and Validity Evaluation project aims to determine benchmarks against which surgeons may compare their own practice.

La clasificación de Clavien-Dindo (CD) es ampliamente utilizada en la notificación de complicaciones quirúrgicas en la literatura científica. Agrupa las complicaciones en función del nivel de intervención necesario para resolverlas y se beneficia de la simplicidad y la facilidad de uso, que contribuyen a su alta fiabilidad entre evaluadores. Ha sido validado para su uso en muchas especialidades debido a la fuerte correlación con las medidas de resultado clave, incluida la duración de la estancia, la calidad de vida posquirúrgica y la remuneración relacionada con el caso. Las limitaciones de la clasificación incluyen la preocupación por diferenciar las complicaciones de grado III y IV y no clasificar las complicaciones intraoperatorias. El Índice Integral de Complicaciones es una adaptación de la clasificación de CD que genera una puntuación de morbilidad de 0 a 100. Se ha propuesto como un método más efectivo para evaluar la carga de morbilidad de los procedimientos quirúrgicos. Sin embargo, sigue siendo menos popular ya que los cálculos de morbilidad son complicados y requieren mucho tiempo. En los últimos años ha habido sugerencias de adaptaciones a la clasificación de CD como la clasificación de Clavien-Dindo-Sink, mientras que en algunas especialidades se han propuesto clasificaciones completamente nuevas debido a la evidencia de que la clasificación de CD no es confiable. De manera similar, el proyecto de Evaluación de Validez y Experiencia Quirúrgica tiene como objetivo determinar puntos de referencia contra los cuales los cirujanos pueden comparar su propia práctica.

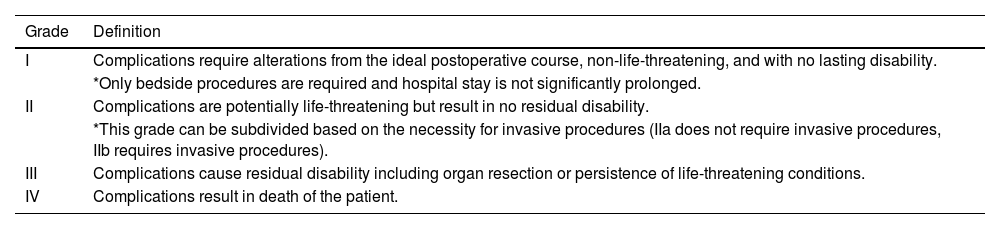

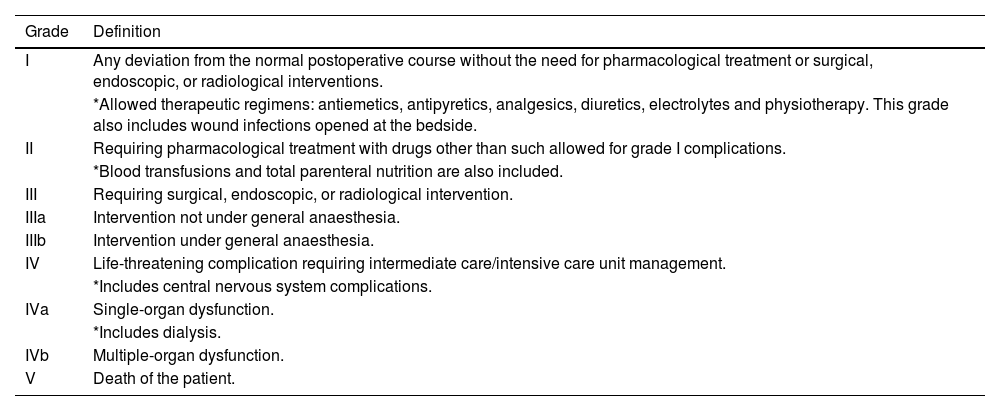

Grading of surgical complications before the suggestion of the Clavien-Dindo (CD) classification lacked standardisation and relied on subjective terminology such as mild, moderate and severe1. This limited the impact of evidence-based medicine in improving surgical outcomes because of difficulty in the interpretation of data. In 1992, Clavien et al. proposed a uniform system for reporting negative surgical outcomes based on the degree of further medical attention required to achieve resolution2. They graded complications from I to IV (Table 1) whereby grade I complications required minor deviations from the planned postoperative course and grade IV indicated the death of a patient resulting from surgical complications. The study analysed 650 cases of elective cholecystectomy, applying the proposed system and pairing it with a modified APACHE II score to assess its usefulness in determining postsurgical prognosis. They concluded that this system allowed for comparisons both within and between hospitals, and for meta-analysis to occur using data from multiple studies and sites. This was the first suggestion of a classification criteria which could be applied universally to surgery, allowing comparison of outcomes across centres, procedures and subspecialties.

Original classification proposed by Clavien et al. in 19922.

| Grade | Definition |

|---|---|

| I | Complications require alterations from the ideal postoperative course, non-life-threatening, and with no lasting disability. |

| *Only bedside procedures are required and hospital stay is not significantly prolonged. | |

| II | Complications are potentially life-threatening but result in no residual disability. |

| *This grade can be subdivided based on the necessity for invasive procedures (IIa does not require invasive procedures, IIb requires invasive procedures). | |

| III | Complications cause residual disability including organ resection or persistence of life-threatening conditions. |

| IV | Complications result in death of the patient. |

Despite this, the proposed criteria were not widely adopted over the following years. This led Dindo et al. (including Pierre-Alain Clavien) to recommend an improved system in 2004 (Table 2)3. They removed subjective wording including ‘minor’ and ‘major’ in order to decrease interobserver variations which may reduce the reliability of the data, and they increased the number of categories from 5 to 7 to allow for better defined groups, to the same effect1. Removal of length of hospitalisation as a criterion further improved the efficacy by allowing for better inter-specialty comparisons because hospital stay is widely variable across surgical subspecialties. Dindo et al. performed a study with a cohort of 6336 participants and including 144 surgeons from 10 different hospitals and with different levels of training3. They reported significant correlations between their system and the complexity of surgery, as well as the length of hospital stay3. They also assessed user-experience by conducting 2 surveys on the participating surgeons, with 92% finding the system to be simple and 92% finding it logical to follow and report3.

Clavien-Dindo classification proposed in 2004 by Dindo et al.3. If a patient experiences a complication at the time of discharge, the suffix ‘d’ for ‘disability’ is added to the grade of the complication. This indicates the need for follow-up to fully evaluate the complication.

| Grade | Definition |

|---|---|

| I | Any deviation from the normal postoperative course without the need for pharmacological treatment or surgical, endoscopic, or radiological interventions. |

| *Allowed therapeutic regimens: antiemetics, antipyretics, analgesics, diuretics, electrolytes and physiotherapy. This grade also includes wound infections opened at the bedside. | |

| II | Requiring pharmacological treatment with drugs other than such allowed for grade I complications. |

| *Blood transfusions and total parenteral nutrition are also included. | |

| III | Requiring surgical, endoscopic, or radiological intervention. |

| IIIa | Intervention not under general anaesthesia. |

| IIIb | Intervention under general anaesthesia. |

| IV | Life-threatening complication requiring intermediate care/intensive care unit management. |

| *Includes central nervous system complications. | |

| IVa | Single-organ dysfunction. |

| *Includes dialysis. | |

| IVb | Multiple-organ dysfunction. |

| V | Death of the patient. |

In the first 5 years following its proposal, the CD classification of surgical complications was used in 214 studies1. The system saw increasing use each year between 2004 and 2009, and the highest uptake was reported in the field of transplantation, which accounted for 31% (49) of these studies1. There is a lack of data reporting the current use of the CD system, however its popularity has increased such that it is now commonplace in the reporting of surgical complications for the purpose of scientific research.

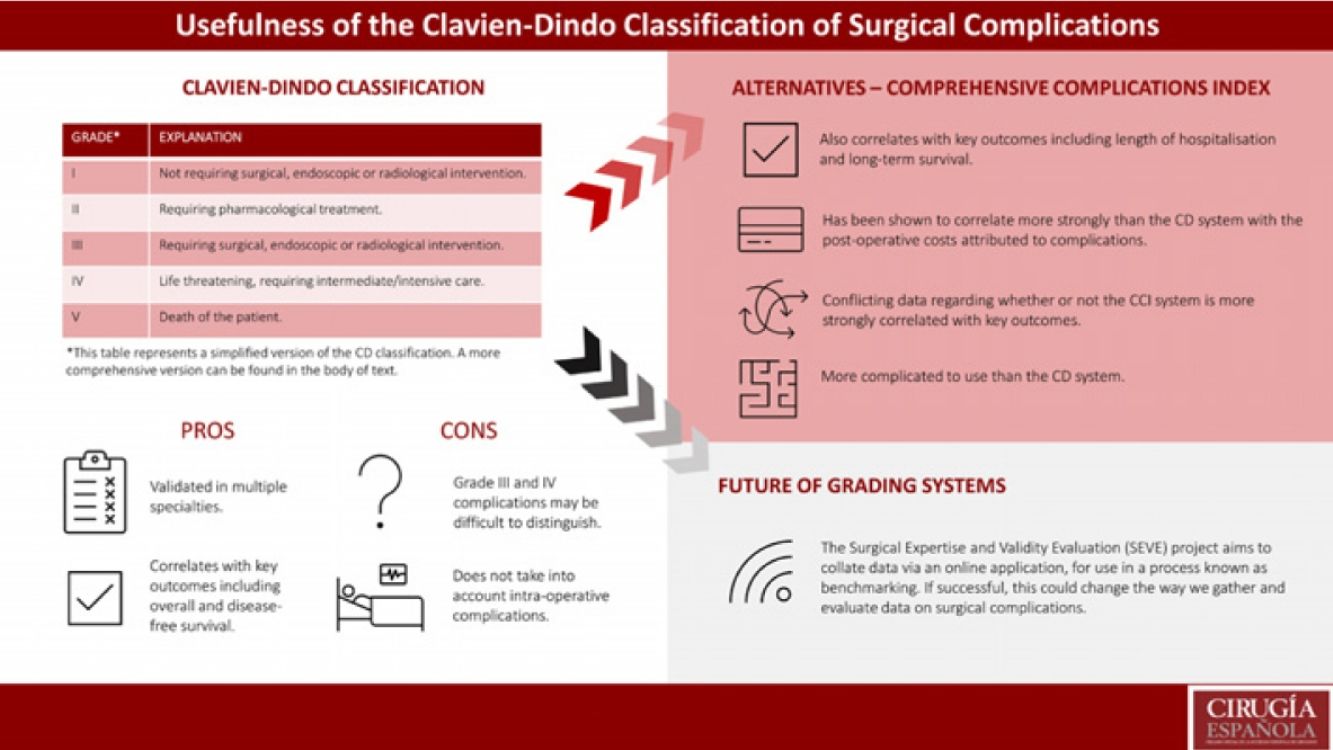

This review aims to assess the pros and cons of the CD classification and to compare it with another commonly used system; the Comprehensive Complications Index (CCI). Considering recent proposals for updated or new classification systems in various specialties, it also aims to discuss whether or not a universal system is beneficial in the reporting of surgical complications, or whether subspecialties would benefit from individualised systems.

Pros and cons of the Clavien-Dindo classificationThe CD classification has clear benefits in helping to improve the surgical management of patients, as evidenced by its validation and use in multiple surgical specialties4–9. Creating a universal system allows for comparison of surgical techniques to determine the safest practice to avoid negative outcomes. Surveys suggest that the CD system is easy to use; all surgeons in a study by Garciá-Garciá et al. found it easy to use, reproducible and logical10. This should not only increase inter-user reliability but encourage the use of the system in more studies because it is not time-consuming or difficult. It must be noted that this was a small cohort of surgeons (n = 4) and that the study was performed only in the field of bariatric surgery. Further benefits to the system include efficiency (average time to classify = 2.5 min/patient) and ease of translation, evidenced by a Kappa Index (K) of 0.85, indicating strong correlation between the original (English) version and the translated (Spanish) version.

The system is also able to predict the occurrence of negative outcomes successfully. Zhengyan et al. studied a cohort of 3091 participants undergoing surgical resection for gastric cancer and reported a significant negative correlation between CD score and overall survival (p = 0.01), as well as CD score and disease-free survival (p < 0.001)11. Similar correlations were identified by Duraes et al., who studied a cohort of 2266 participants also undergoing colorectal cancer resection12. Wang et al. corroborated these studies in a cohort of 614 elderly patients (aged 65 or more), showing that the CD system maintains validity in older populations13. CD grading has also been shown to correlate with length of postsurgical hospitalisation14 and change in quality of life (QOL) during the early postoperative period (≤6 weeks postoperative)15. Bosma et al. also found that severe complications (those graded III, IV or V) significantly correlate with decrease in physical and psychological QOL during this period15.

CD grading has also been validated economically. Téoule et al. reported that case-related renumeration (a proxy for the cost of postoperative complications) positively correlated with CD grade, suggesting that higher grade complications cost more to resolve14. This supports the use of the CD system in performing financial analyses of surgical procedures.

The CD system is not without limitations. Some of these relate to difficulty distinguishing grade III from grade IV surgical complications. First, the use of general anaesthesia (GA) (distinguishing IIIb complications from IIIa) may not correlate with the seriousness of intervention required to treat a patient. One such scenario has been outlined in the field of urology, where urethral stenting and surgical urethral repair may both be performed under GA despite the latter indicating more serious morbidity16. This highlights a limitation in the use of required intervention as a proxy for negative surgical outcomes; morbidity may not entirely correlate with the intervention required to treat it, which is dependent on the nature of the complication and the tools available to treating healthcare professionals. Another limitation of the CD classification is the difference in treatment decisions between healthcare professionals. Where a procedure may be performed under GA in one hospital, another may opt for local anaesthesia16. Clinical decision making is also relevant to grade IV complications because the decision to treat a patient in intensive care may differ between hospitals16. The limitations described above suggest that the CD classification may be subject to interobserver variability, however Garciá-Garciá et al. report the system as having a Kappa Index of 0.92, indicating high interobserver reliability10.

There are also limitations regarding the interpretation of data published using this system. Studies from hospitals with the financial means to perform complicated postoperative interventions may report data that suggest procedures to be safe, though this may not be the case where these interventions are not available. This could lead to hospitals performing procedures with recognised complications that they are not prepared to treat, increasing negative outcomes. This limitation is not purely economic and may also occur due to the skills-gap between different healthcare professionals. An intervention may be possible in a setting where healthcare professionals have a higher level of training, but this same intervention may be beyond the training of those in a different hospital. This could also cause misleading data whereby surgical procedures are reported as more or less safe than they really are.

CD grading does not offer a classification for intraoperative complications which may result in alterations to the postoperative course as well as financial implications. In addition, attempts to classify intraoperative complications may lead to confusion. For example, if a complication occurs and is treated during an operation and does not result in prolonged hospitalisation it may be considered a grade I complication. However, it may also be considered grade III as it required surgical intervention17. For these reasons, modifications have been suggested to include intraoperative complications17–19.

Finally, CD classification is based on the actions of treating physicians which occur after the complication arises. Due to this, it may be subject to the Hawthorne Effect, whereby the actions of individuals who know they are being assessed are different (and often more productive) to those who do not20. It has been suggested that by implementing regular review of all complications this could be negated, as the treating physician would feel as though they are always being assessed20.

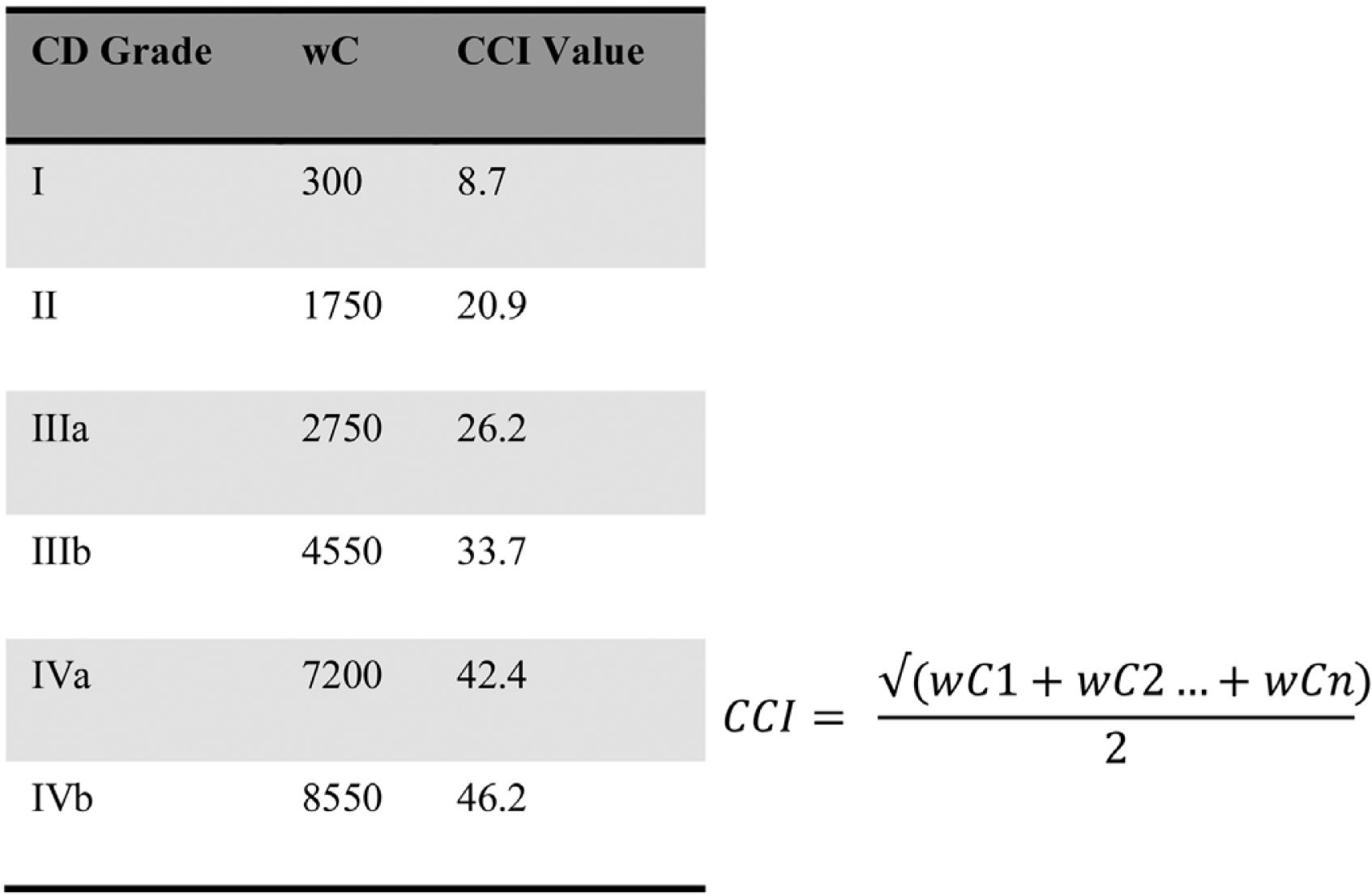

Clavien-Dindo classification vs. Comprehensive Complication IndexThe most popular alternative to the CD system in recent years has been the Comprehensive Complication Index (CCI) (Fig. 1). In 2013, Slankamenac et al. proposed the CCI on the basis that many studies using the CD classification only reported the grade of the most significant complication for each patient21. They argued that without reporting so-called ‘lesser’ complications as well, it was impossible to understand the true burden of morbidity associated with a procedure. The CCI is reported as a scale from 0 to 100 where 0 is an uncomplicated procedure and score increases with burden of complications. Each complication is weighted in terms of severity based on its CD grade and generates an individual score, and these are added to generate a total. Slankamenac et al. performed 4 validations of the CCI, concluding that it discriminates better amongst patients than the CD system21.

Comprehensive Complications Index as proposed by Slankamenac et al. in 201321. CD grade V complications always result in a score of 100.

In 2014, Slaman et al. analysed data from 621 patients who underwent oesophagectomy between 1993 and 2005. They compared the CD system with the CCI and found that CCI correlated more strongly with LOS, prolonged LOS, reintervention and reoperation22. A 2018 study of patients with inflammatory bowel disease corroborated these findings with respect to LOS23. CCI has also been shown to correlate with number of comorbidities, duration of surgery and procedure complexity24, though the CD system was also found to correlate with these measures, and the paper does not report on the differences in accuracy between the two systems of classification. In addition, recent evidence suggests that CCI is a more strongly correlated with postoperative cost (attributed to complications) than CD (CCI vs. CD, r = 0.744 vs. r = 0.723, p < 0.001)25; CCI may be better for use in analysis of the financial impact of postoperative complications.

Despite the above indications that CCI may be more accurate in its depiction of the postoperative period, some studies have reported no significant difference between the two systems13,26. Wang et al. looked at long-term survival in 614 elderly patients undergoing radical colorectal cancer resections and identified no significant difference between CD and CCI as predictors of long-term overall survival; increases in both CD grade and CCI score were associated with decreased long-term overall survival13. Survival was assessed at 1-, 3- and 5-years following surgery13. Ray et al. investigated a cohort of 1000 patients undergoing gastrointestinal and hepatopancreaticobiliary surgery and reported no significant difference between the CD and CCI classifications in measuring LOS, stay in intensive care or time to normal activity26. They therefore advocated the use of the CD system over the CCI in order to save time and for the simplicity of determining the grade/score26.

Further options for the grading of surgical complicationsMany adaptations to the CD system have recently been suggested to make it more applicable to individual specialties. The Clavien-Dindo-Sink classification is increasingly used in paediatric orthopaedic surgery owing to improved inter- and intra-rater reliability27. This system still grades complications from I to IV and is still based on the level of intervention required to treat, but each grade has been changed so that the levels of intervention relate better to orthopaedic surgery. For example, grade III is defined as ‘a complication that is treatable but requires surgical, endoscopic, or radiographic procedure(s), or an unplanned hospital readmission’27. This re-definition of the CD system means that inter-specialty comparisons would no longer be reliable but may help to improve complications reporting in paediatric orthopaedic surgery. Modifications to the CD system have also been suggested and validated in retinal detachment surgery28, endoscopy for nephrolithiasis29 and adult spinal deformity surgery30.

In some specialties it has also been suggested that a total deviation from the use of the CD classification would improve reporting of postsurgical complications. Despite validation of the CD classification in head and neck surgery31, multiple studies suggest that specific system for head and neck surgery would be beneficial31,32. The reasons for this relate to discrepancies between the perceived seriousness of the complication and the CD grade assigned. Monteiro et al. suggest that CD grades do not effectively grade wound complications, which are very common in head and neck surgery, and that the requirement of returning to the operating theatre to treat a complication does not correlate strongly enough with its severity31. In paediatric urological surgery the CD system has been found to be unreliable, leading to the suggestion that a different classification must be developed. Dwyer et al. compared the accuracy of the CD classification in paediatric urology to that reported in the 2004 paper by Dindo et al. (which reported on adult surgeries)3,33. They found that accuracy fell from 90% in adults to 75% in children (p < 0.001). They also carried out a survey to assess the perceived appropriateness of the CD system amongst paediatric urologists and reported that only 49% found it appropriate for children, while 89% felt it was appropriate for adults.

Finally, the Surgical Expertise and Validity Evaluation (SEVE)34 project aims to develop a new model for evaluating surgical complications based on the collection and statistical analysis of data from different surgeons at different sites, performing the same categories of operations. They hope to identify the best possible outcomes for procedures and to use these as a standard against which to compare usual practice. This process is known as benchmarking. They will also develop an online application onto which new data can be uploaded from participating centres around the world. The SEVE project is currently undertaking a pilot study across Europe. If successful, this project could allow for more efficient collation of data and enable us to compare surgical outcomes to the highest possible standard, individualised to specific surgical procedures.

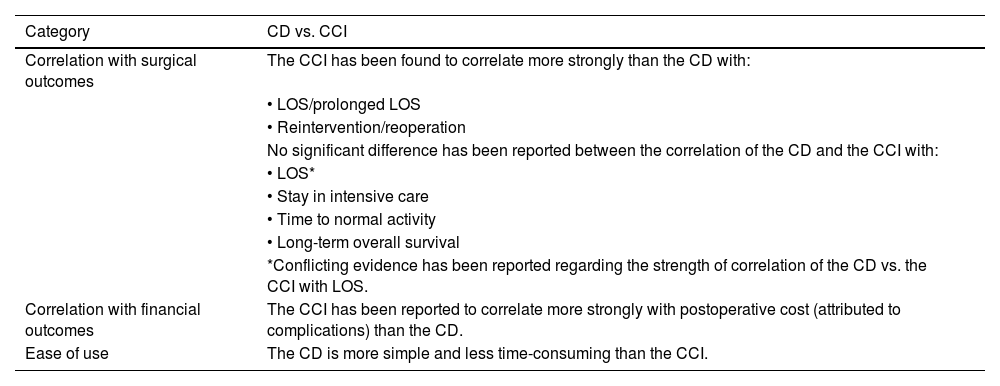

ConclusionSince 2004, the Clavien-Dindo classification of surgical complications has allowed for uniform reporting of postsurgical complications and has been validated for use in a wide-range of surgical specialties. Its simplicity has led to good inter-rater reliability and means negative outcomes can be reported and interpreted effectively. Despite this, recent years have seen an increasing number of researchers suggest modifications to the system. One such modification is the Comprehensive Complication Index, which is more complex but acts as a better predictor of total burden of morbidity following postsurgical complications. Table 3 compares the CD classification to the CCI.

Comparison of the Clavien-Dindo classification and the Comprehensive Complication Index.

| Category | CD vs. CCI |

|---|---|

| Correlation with surgical outcomes | The CCI has been found to correlate more strongly than the CD with: |

| • LOS/prolonged LOS | |

| • Reintervention/reoperation | |

| No significant difference has been reported between the correlation of the CD and the CCI with: | |

| • LOS* | |

| • Stay in intensive care | |

| • Time to normal activity | |

| • Long-term overall survival | |

| *Conflicting evidence has been reported regarding the strength of correlation of the CD vs. the CCI with LOS. | |

| Correlation with financial outcomes | The CCI has been reported to correlate more strongly with postoperative cost (attributed to complications) than the CD. |

| Ease of use | The CD is more simple and less time-consuming than the CCI. |

Adaptations have also been suggested, most notably in paediatric orthopaedic surgery, to allow grades of complication to fit better with specific specialties. Completely new classification systems have also been proposed in some specialties, either because clinicians do not feel the classification relates strongly enough to their specialty or because the Clavien-Dindo system has been proved inaccurate, as with paediatric urological surgery. Finally, the SEVE project is currently being validated across Europe and aims to use benchmarking to improve the ease of comparisons of everyday surgical outcomes with the perceived gold standard.