Se realiza una actualización (año 2010) de la Guía de práctica clínica de la sociedad española de diálisis y trasplante sobre las actitudes frente a la infección en diálisis. Se han consensuado 31 puntos, de los cuales 17 se refieren a la hemodiálisis, 11 se refieren a la diálisis peritoneal y 3 a aspectos comunes de las dos técnicas de diálisis, todos con bibliografía médica.

An update (year 2010) of Guide of clinical practice of the Spanish Society of Dialysis and transplants is realised on the attitudes against infection in dialysis; 31 points are agreed upon, of which 17 talk about haemodialysis, 11 talk about peritoneal dialysis and 3 about common aspects of the two techniques of dialysis, all with medical bibliography.

Infectious processes are one of the most frequent complications in chronic renal insufficiency, without underestimating other conditions that are no less important such as cardiovascular, anaemia and osteodystrophy.

Infection, in anybody's life and whatever its origin or location, usually occupies a fundamental protagonism due to its repercussion on daily life, given the limitations conditioned by a high temperature that is frequent in microbial infection or in its absence and the perception of a physical condition with evident decline. This is one of the main reasons why the public, from infancy to old age, is obliged to go to the doctor's surgery or a hospital.

The reason for these guidelines is to be able to review, in a practical way and in specific paragraphs, what have been considered as the most dominant disorders or even those that because of their repercussion, even with lesser importance, bring about worries before taking medical decisions. We have concentrated on the area of chronic renal insufficiency in dialysis patients because of their special characteristics and the adequacy of the dose or pharmacological inconveniences that are inherent to their condition and yet are not applicable to the rest of the population. They present infectious complications (respiratory, renal, abdominal, cutaneous) similar to those suffered by the rest of the general public, however with a difference that they already have a base or different foundation, as is chronic renal insufficiency, which conditions the response to the infectious aggression because the capacity of defence is lesser on having reduced immunity and therefore makes them more vulnerable.

Infection causes an important level of morbidity in the group of people who must undergo substitutive treatment, since according to statistics, 2 out of each 5 hospital admissions are due to infections. On examination of a sample of 275 patients in a cross section in 2003, this reflected an average of 0.6 admissions/patient/year, of which 40% were due to infection and in diabetics this ratio should be multiplied by 2.5. These data indicate the importance of the impact of this disorder as far as morbidity is concerned and whose mortality was 13% (in the literature examined this varies between 10% and 40%), exceeded only by cardiovascular infections.

There will without a doubt be discrepancies concerning personal experiences or protocols that are used, but in our daily work it is usual to have more than one therapeutic options available for each illness, for which reason we must choose the most appropriate in each case among various that are published consensually. Future knowledge must modify, if necessary, the decisions made in each of the paragraphs or guidelines.

Haemodialysis (HD)Guideline 1Prophylaxis measures are effective in preventing spontaneous or transmitted infections. Corporal hygiene is essential, especially around the access area. Barrier precautions, such as gloves, face masks and waterproof skin dressings are compulsory to avoid horizontal transmission. The use of sterile material and adequate antiseptics is required in any handling of the patient. Health professionals must maximize prophylaxis and preventative measures in any intervention on vascular access for dialysis and maintain adequate training. Screening of nasal colonisation should be carried out on all patients but especially those with catheters. Carriers of nasal staphylococcus, both patients and health professionals, must receive treatment with mupirocin of 2 daily applications for 5 days. Carrier patients of infected skin lesions shall receive the treatment indicated but should cover the area of the lesion.

ReferencesArgüello C, Demetrio AM, Chacon M. Manual de Infecciones Intrahospitalarias, medidas generales de prevención y control. Hospital Santiago Oriente-Dr. Luis Tisné Bronsse; 2004.

Association for Professionals in Infection Control and Epidemiology. Guideline for handwashing and hand antisepsis in health care settings. Am J Infect Control 1995;23:251–69.

Bloom S, Fendrick AM, Chernew ME, Patel P. Clinical and economic effects of mupirocina calcium on preventing Staph. aureus infection in hemodialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis 1996;27:687–94.

Chow JW, Yu VL. Staphylococcus aureus nasal carriage in hemodialysis patients. Its role in infection and approaches to prophylaxis. Arch Intern Med 1989;149:1258–62.

Corbella X, Dominguez MA, Pujol M, Ayats J, Sendra M, Pallares R, et al. Staphylococcus aureus nasal carriage as a marker for subsequent staphylococcal infections in intensive care unit patients. Em J Clin Micro Infect Dis 1997;16:351–7.

Davison AM, Kessler M. European best practice guideline for hemodialysis. Part I. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2002;17:72–8.

Gaspar MC, Uribe P, Sánchez P, Coello R, Cruzet F. Personal hospitalario portador nasal de Stafilococo resistente a Meticilina. Utilidad del tratamiento con mupirocina. Enf Infect Microb Clin 1992;10:109–10.

Guidelines for environmental infection control in health-care facilities. Recommendations of CDC and the Health-care Infections Control Practices Advisory Committee. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention—Federal Government Agency (US); 2003. p. 1–42.

Guideline: Recommendations for preventing transmission of infections among chronic hemodialysis patients. MMWR Recomm Rep. 50(RR-5), 2001. p. 1–43.

Marjolein F, Vandenbergh Q, Yzerman F, Belkman A, Boelens H, Sijmons M, et al. Follow-up of Staphylococcus aureus nasal carriage after 8 years: redefining the persistent carrier state. J Clin Microbiol 1999;37:3133–40.

NFK/DOQI. National Kidney Foundation. Clinical practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease. Am J Kidney Dis 2002;39: 51–246.

Asociación Nefrológica de la ciudad de Buenos Aires. Normas de bioseguridad universales para su aplicación en los servicios de hemodiálisis. Conclusiones de las primeras jornadas de Bioseguridad en Diálisis: Consejo de Hemodiálisis. Nephrol Dial Transplant 1994;35:1–18.

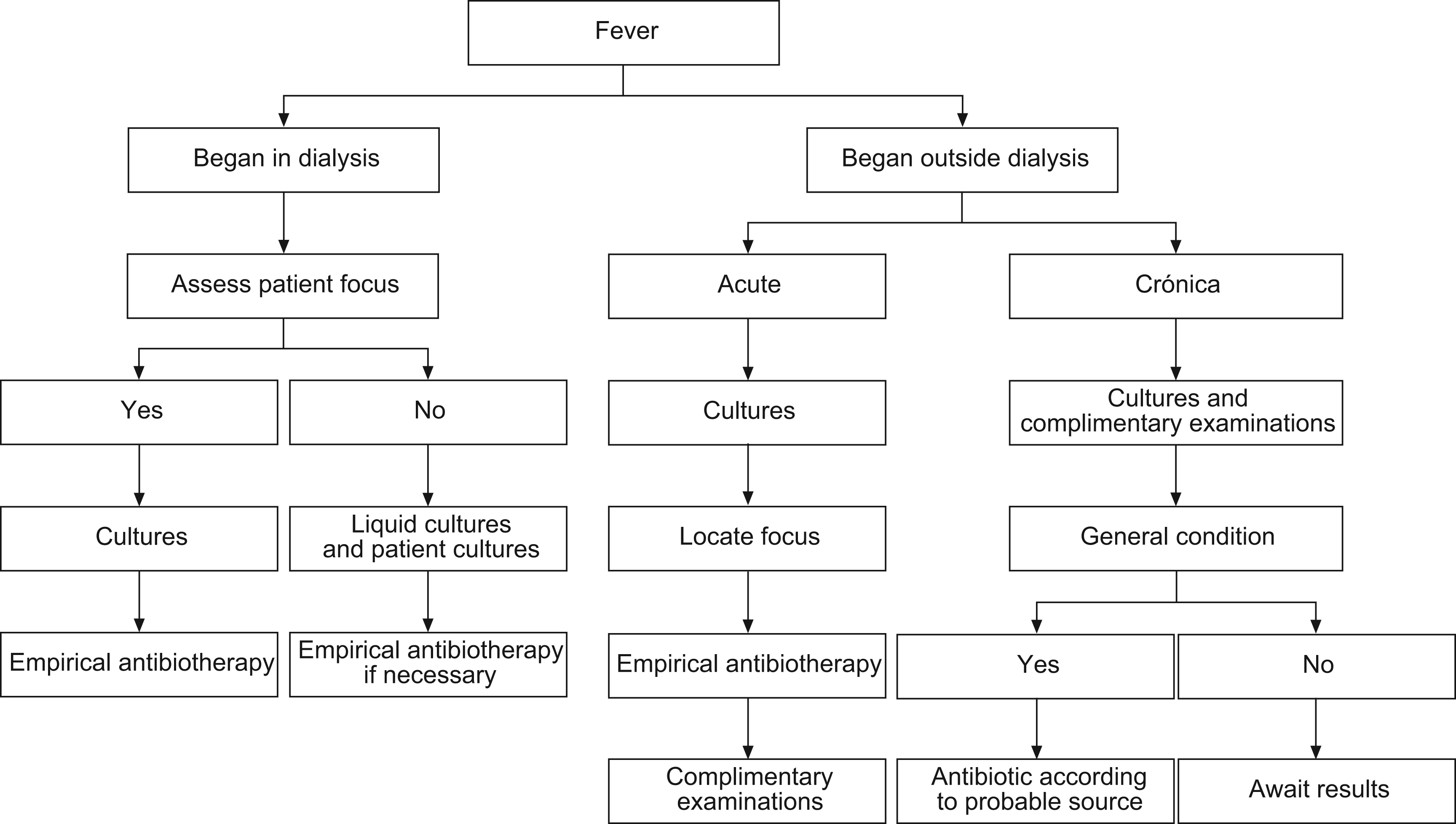

Guideline 2Fever is the main symptom of infection. Fever that appears at the start of or during dialysis allows access-related infection, contamination of the dialysate or fungible material, first use syndrome, hypersensitivity reaction, pyrogenic, haemolysis or an inadequate temperature of the monitor to be ruled out. Fever originating during dialysis makes it necessary to apply the medical procedure of usual diagnosis of location and identification.

Elderly people may experience fever with hardly a high temperature, in which case when presented with toxicity symptoms, an infectious source should be ruled out as a reason for the problem. Concomitant treatment with non-steroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or analgesics can mask this symptom (figure).

Fig. 1. Diagram of procedure in the case of fever.

Fever can appear alone or accompanied by bacteremia, with local symptoms in some area of the body or after instrumental manipulation (drip feeds, catheterisation, blood collection), surgical interventions, wounds, skin or vessel infections. A high fever accompanied by shivering, increase in heart rate, perspiration, hypotension, pain, cephalea and vomiting is a symptom of acute bacteremia, wherefore it is necessary to carry out, whenever possible and before any other treatment, a culture of the biological liquids in order to know the source and possible systematic extension. Afterwards steps must be taken as soon as possible in order to avoid a possible septic shock.

Chronic infection should be suspected in the presence of symptoms that are seen to progress with time, although the illness does not appear as explained for acute processes, symptoms such as low-grade fever, intermittent perspiration (day or night), weight loss, anaemia (poor response to erythropoietin [EPO]), positive PCR, hypoalbuminemia (desnutrition) and poor tolerance to dialysis (figure and table) are observed (even if not all of them).

Table 1. Difference between acute and chronic infection

| Acute infection | Chronic infection |

| High fever | Low-grade fever |

| Shivers | Intermittent perspiration |

| Tachycardia | Weight loss |

| Perspiration | Anaemia |

| Hypotension | Positive PCR |

| Pain | Hypoalbuminemia |

| Cephalea | Poor tolerance to dialysis |

| Vomiting | High ferritin level |

Abbott KC, Agodoa LY. Etiology of bacterial septicemia in chronic dialysis patients in the United States. Clin Nephrol 2001;56:124–31.

Canaud BJ, Bosc JY, Leray H, Morena M, Stec F. Microbiologic purity of dialysate: rationale and technical aspects. Blood Purif 2000;18:200–13.

Canaud BJ, Mion CM. Water treatment for contemporary haemodialysis. In: Jacobs C, Kjellstrand CM, Koch KM, Wincester JF, editors. Replacement of renal function by dialysis. 4th ed. Dondrecht: Kluwer Academic; 1996. p. 231–55.

Dauguirdas JT, Blake PG, Todd S. Handbook of dialysis. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2001. Segunda edición española. Barcelona: Masson; 2003. p. 518–44.

Hoen B, Kessler M, Hestin D, Mayeux D. Risk factors for bacterial infections in chronic haemodialysis adult patients: a multicentre prospective survey. Nephrol Dial Transplant 1995;10:377–81.

Morin P. Identification of the bacteriological contamination of a water treatment line used for haemodialysis and its disinfection. J Hosp Infect. 2000;45:218–24.

NKF/DOQI Clinical Practice Guidelines for vascular Access. Am J Kidney Dis 2001;37(Suppl. 1):137–81.

Pérez-García R. Complicaciones agudas en hemodiálisis. En: Lorenzo V, Torres A, Hernández D, Ayus JC, editores. Manual de Nefrología. 2nd ed. Madrid: Harcourt; 2002. p. 427.

Perez-Garcia R, Rodriguez-Benitez PO. Why and how to monitor bacterial contamination of dialysis? Nephrol Dial Transplant 2000;15:760–4.

Protocols de malalties infeccioses. Servei de Malalties Infeccioses. Hospital Vall d’Hebron. Barcelona: Servei Català de la Salut; 2003.

Roth VR, Jarvis WR. Outbreaks of infection and/or pyrogenic reactions in dialysis patients. Semin Dial 2000;13:92–6.

Swartz RD, et al. Hypothermia in the uremic patient. Dial Transplant 1983;12:584.

Tielemans C, Husson C, Shurmans T, et al. Effects of ultrapure and non-sterile dialysate on the inflammatory response during in vitro haemodialysis. Kidney Int 1996;49:236–43.

Tokars JI. Blood stream infections in hemodialysis patiens: getting some deserved attention. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2002;23:713–5.

Guideline 3The most frequent microorganisms found in infectious processes are: Gram-negative bacilli (50%), Gram-positive cocci (40%), anaerobes (5%) and others (5%). In cases of nosocomial infection a higher prevalence of Gram-negative germs is observed, with greater resistance to antibiotics (table).

Table 2. Microorganisms involved in infectious processes

| Gram-positive bacteria | Gram-negative bacteria |

| Staplylococcus aureus, S. epidermidis | Escherichia coli |

| Methicillin-resistant S. aureus | Klebsiella |

| Enterococcus | Proteus |

| Streptococcus | Haemophilus |

| S. pneumoniae | Enterobacter |

| Bacillus | Pseudomonas aeruginosa |

| Clostridium | Serratia |

| Corynebacterium | Salmonella |

| Citrobacter | |

| Legionella | |

| Acinetobacter | |

| Other pathogens | |

| Mycoplasma | Chlamydia |

| Fungi | |

| Candida | Aspergillus |

The most frequent location of infection in dialysis patients is found in this order: dialysis access (38%), in which 75% are through the catheter; reno-urological (20%); respiratory tracts (18%); abdomen (9%) and other localities (15%).

Those multiple germs that because of their frequency are the most common in the cultures of our patients shall be explained in detail and others which, although less frequent, require a possible specific treatment or isolation.

If infection is suspected due to local aspect (signs of inflammation or secretion) or general (fever. etc.), clinical criterion of confirmation and localisation shall be established and an etiological hypothesis is necessary based on the medical history, location and background.

If staphylococci infection is suspected, since there is a high rate of resistance to methicillin in dialysis patients, empirical treatment with daptomycin shall be administered. This is the same or more efficient and less toxic than vancomycin and unlike the latter, is as efficient as Cloxacillin against staphylococci sensitive to methicillin (SSM). SEIMC and SEQ treatment Guidelines recommend this.

If Gram-negative bacilli is suspected, third generation Cephalosporin is recommended with or without an aminoglycoside (table).

ReferencesBaj W, Molina M, Rosenthal AF, DiDominic V, Bander SJ. Incidence of bacteremia in hemodialysis patiens, 1993–1994. J Am Soc Nephrol 1995;6:657.

Barcenas CG, Fuller TJ, Elms J, Cohen R, White MG. Staphylococcal sepsis in patients on chronic hemodialysis regimens. Intravenous treatment with vancomycin given once weekly. Arch Intern Med 1976;136:1131–4.

Barth RH, de Vinzenzo N. Use of vancomycin in high-flux hemodialysis: experience with 130 courses of therapy. Kidney Int 1996;50;929–36.

Bloom S, et al. Clinical and economic effects of mupirocina calcium on preventing S. aureus infection in hemodialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis 1996;27:687–94.

Cosgrove, Sara, Fowler, Vance G. Management of Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus Bacteremia. Clin Infect Dis 2008.

Dauguirdas JT, Blake PG, Todd S. Handbook of dialysis. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2001. Segunda edición española. Barcelona: Masson; 2003. p. 518–44.

Fowler, Vance G, et al. Daptomycin versus standard therapy for Bacteremia and Endocarditis caused by Staphylococcus aureus. N Engl J Med 2006.

Gudiol F, Aguado JM, Pascual A, Pujol M, Almirante B, et al. Documento de consenso sobre el tratamiento de la bacteriemia y la endocarditis causada por Staphylococcus aureus resistente a la Meticilina. Enferm Infect Microbiol Clin 2009

Haijar J, Girard R, Marc JM, Ducruet L, Bernard M, Fadel B, et al. Surveillance of infections in chronic hemodialysis patients. Nephrologie 2004;25:133–40.

Hamory BH. Nosocomial bloodstream and intravascular device related infections. In: Wenzel RP, editor. Prevention and control of nosocomial infections. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1987. p. 283–319.

Henderson DK. Bacteremia due to percutaneous intravascular devices. In: Mandell GL, Douglas RG, Bennett JE, editors. Principles and practice of infectious disease. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1990. p. 2189–99.

Hoen B, Paul Dauphin A, Hestin D, Kessel M (EPIBACDIAL). Multicenter prospective study of risk factor bacteremia in chronic hemodialysis patients. J Am Soc Nephrol 1998;9:869–76.

Honorato J. Fármacos y diálisis. Dial Traspl 2010;31:47–53.

Keane WF, Shapuro FL, Raij L. Incidence and type of infections occurring in 445 chronic hemodialysis patients. Trans Am Soc Artif Intern Organs 1977;23:41–7.

Kessler M, Hoen B, Mayeux D, Hestin D, Fontenaille C. Bacteremia in patients on chronic hemodialysis. A multicenter prospective survey. Nephron 1993;64:95–100.

Mensa J, Gatell JM, Martínez JA, Torres A, Vidal F, Serrano R, et al. Terapéutica antimicrobiana (infecciones en urgencias). 5.a ed., Antares; 2005.

Mensa J, Barberán P, Llinares P, Picazo JJ, Bouza E, Álvarez Lerma F, et al. Guía de tratamiento de la infección producida por Staphylococcus aureus resistente a Meticilina. Rev Esp Quimioter 2008.

Nsouli KA, Lazarus M, Schoenbaum SC, Gottlier MN, Lowrie EG, Shocair M. Bacteriemic infection in hemodialysis. Arch Intern Med 1979;139:1255–8.

Protocols de malalties infeccioses. Servei de Malalties Infeccioses. Hospital Vall d’Hebron. Barcelona: Servei Català de la Salut; 2003.

Trimarchi H, Lafuente P, Suki WN. Ceftriaxone is an efficient component of antimicrobial regimens in the prevention and initial management of infections in end-stage renal disease. Am J Nephrol 2000;20:391–5.

Guideline 4For treatment of methicillin-resistant S. aureus or coagulase-negative Staphylococcus, daptomycin or vancomycin are recommended but only when the MIC for this second antibiotic is less or equal to 1; if greater than 1, daptomycin is recommended.

If the addition of aminoglycoside is considered, it is advisable to combine it with daptomycin in order to avoid possible nephrotoxicities that may appear if combined with Vancomycin.

If a fungus infection is suspected (usually Candida albicans), the use of an adjusted dose of fluconazole is recommended.

ReferencesBaj W, Molina M, Rosenthal AF, DiDominic V, Bander SJ. Incidence of bacteremia in hemodialysis patients, 1993–1994. J Am Soc Nephrol 1995;6:657.

Barcenas CG, Fuller TJ, Elms J, Cohen R, White MG. Staphylococcal sepsis in patients on chronic hemodialysis regimens. Intravenous treatment with vancomycin given once weekly. Arch Intern Med 1976;136:1131–4.

Barth RH, de Vinzenzo N. Use of vancomycin in high-flux hemodiálisis: experience with 130 courses of therapy. Kidney Int 1996;50:929–36.

Bloom S, et al. Clinical and economic effects of mupirocina calcium on preventing S. aureus infection in hemodialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis 1996;27:687–94.

Cosgrove, Sara, Fowler, Vance G. Management of Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus Bacteremia. Clin Infect Dis 2008.

Dauguirdas JT, Blake PG, Todd S. Handbook of dialysis. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2001. Segunda edición española. Barcelona: Masson; 2003. p. 518–44.

Haijar J, Girard R, Marc JM, Ducruet L, Bernard M, Fadel B, et al. Surveillance of infections in chronic hemodialysis patients. Nephrologie 2004;25:133–40.

Hamory BH. Nosocomial bloodstream and intravascular device related infections. In: Wenzel RP, editor. Prevention and control of nosocomial infections. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1987. p. 283–319.

Henderson DK. Bacteremia due to percutaneous intravascular devices. In: Mandell GL, Douglas RG, Bennett JE, editors. Principles and practice of infectious disease. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1990. p. 2189–99.

Hoen B, Paul Dauphin A, Hestin D, Kessel M (EPIBACDIAL). Multicenter prospective study of risk factor bacteremia in chronic hemodialysis patients. J Am Soc Nephrol 1998;9:869–76.

Keane WF, Shapuro FL, Raij L. Incidence and type of infections occurring in 445 chronic hemodialysis patients. Trans Am Soc Artif Intern Organs 1977;23:41–7.

Kessler M, Hoen B, Mayeux D, Hestin D, Fontenaille C. Bacteremia in patients on chronic hemodialysis. A multicenter prospective survey. Nephron 1993;64:95–100.

Mensa J, Gatell JM, Martínez JA, Torres A, Vidal F, Serrano R, et al. Terapéutica antimicrobiana (infecciones en urgencias). 5th ed. Antares; 2005.

Nsouli KA, Lazarus M, Schoenbaum SC, Gottlier MN, Lowrie EG, Shocair M. Bacteriemic infection in hemodialysis. Arch Intern Med. 1979;139:1255–8.

Protocols de malalties infeccioses. Servei de malalties infeccioses. Hospital Vall d’Hebron. Barcelona: Servei Català de la Salut; 2003.

Trimarchi H, Lafuente P, Suki WN. Ceftriaxone is an efficient component of antimicrobial regimens in the prevention and initial management of infections in end-stage renal disease. Am J Nephrol. 2000;20:391-5.

Zarate MS, Jorda-Vargas L, Lanza A, et al. Estudio microbiológico de bacteriemias y funguemias en pacientes en hemodiálisis crónica. Rev Argent Microbiol. 2005;37:145-9.

Guideline 5In cases of an allergy to beta-lactams, when neither Cloxacillin nor first generation cephalosporins can be used, the use of daptomycin is recommended instead of vancomycin, since daptomycin is an anti-staphylococcus just as efficient as beta-lactams.

ReferencesBarcenas CG, Fuller TJ, Elms J, Cohen R, White MG. Staphylococcal sepsis in patients on chronic hemodialysis regimens. Intravenous treatment with vancomycin given once weekly. Arch Intern Med 1976;136:1131–4.

Bloom S, et al. Clinical and economic effects of mupirocina calcium on preventing S. aureus infection in hemodialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis 1996;27:687–94.

Dauguirdas JT, Blake PG, Todd S. Handbook of dialysis. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2001. Segunda edición española. Barcelona: Masson; 2003. p. 518–44.

Fowler, Vance G, et al. Daptomycin versus standard therapy for Bacteremia and Endocarditis caused by Staphylococcus aureus. N Engl J Med 2006.

Haijar J, Girard R, Marc JM, Ducruet L, Bernard M, Fadel B, et al. Surveillance of infections in chronic hemodialysis patients. Nephrologie 2004;25:133–40.

Hamory BH. Nosocomial bloodstream and intravascular device related infections. In: Wenzel RP, editor. Prevention and control of nosocomial infections. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1987. p. 283–319.

Henderson DK. Bacteremia due to percutaneous intravascular devices. In: Mandell GL, Douglas RG, Bennett JE, editors. Principles and practice of infectious disease. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1990. p. 2189–99.

Hoen B, Paul Dauphin A, Hestin D, Kessel M (EPIBACDIAL). Multicenter prospective study of risk factor bacteremia in chronic hemodialysis patients. J Am Soc Nephrol 1998;9:869–76.

Honorato J. Fármacos y diálisis. Dial Traspl 2010;31:47–53.

Keane WF, Shapuro FL, Raij L. Incidence and type of infections occurring in 445 chronic hemodialysis patients. Trans Am Soc Artif Intern Organs 1977;23:41–7.

Kessler M, Hoen B, Mayeux D, Hestin D, Fontenaille C. Bacteremia in patients on chronic hemodialysis. A multicenter prospective survey. Nephron 1993;64:95–100.

Mensa J, Gatell JM, Martínez JA, Torres A, Vidal F, Serrano R, et al. Terapéutica antimicrobiana (infecciones en urgencias). 5th ed. Antares; 2005.

Nsouli KA, Lazarus M, Schoenbaum SC, Gottlier MN, Lowrie EG, Shocair M. Bacteriemic infection in hemodialysis. Arch Intern Med 1979;139:1255–8.

Protocols de malalties infeccioses. Servei de Malalties Infeccioses. Hospital Vall d’Hebron. Barcelona: Servei Català de la Salut; 2003.

Barth RH, de Vinzenzo N. Use of vancomycin in high-flux hemodialysis: experience with 130 courses of therapy. Kidney Int 1996;50:929–36.

Trimarchi H, Lafuente P, Suki WN. Ceftriaxone is an efficient component of antimicrobial regimens in the prevention and initial management of infections in end-stage renal disease. Am J Nephrol. 2000;20:391–5.

Baj W, Molina M, Rosenthal AF, DiDominic V, Bander SJ. Incidence of bacteremia in hemodialysis patients, 1993–1994. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1995;6:657.

Guideline 6If an internal arteriovenous fistula infection is suspected, either autologous or due to a prosthesis, we should anticipate 2–3 weeks of treatment, intravenously and following dialysis.

In the case of tunnel catheters, the same treatment as mentioned earlier is proposed, in the absence of a serious medical condition or lack of response 72h after applying the treatment.

Withdrawal of the access is proposed in the case of septic shock and in the case of a history of valvulopathy or clinical suspicion of fungal infection. In circumstances of clinical stability, the withdrawal shall be decided after a lack of response after 2–3 weeks.

ReferencesBailey E, Berry N, Cheesbrough JS. Antimicrobial lock therapy for catheter related bacteremia among patients on maintenance haemodialysis. J Antimicrob Chemother 2002;50:615–7.

Berrington A, Kate Gould F. Use of antibiotic locks to treat colonized central venous catheters. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2001;48: 597–603.

Capdevila JA, Segarra A, Planes AM, Ramirez-Arellano M, Pahisa A, Piera L, et al. Successful treatment of haemodialysis catheterrelated sepsis without catheter removal. Nephrol Dial Transplant 1993;8:231–4.

Cercenado E, Ena J, Rodriguez-Creixems M, Romero J, Bouza E. A conservative procedure for the diagnosis of catheter related infections. Arch Intern Med 1990;150:1417–20.

Chatzinikolaou I, Finkel K, Hanna H, Boktour M, Foringer J, Ho T, et al. Antibiotic-coated hemodialysis catheters for the prevention of vascular catheter-related infections: a prospective, randomized study. Am J Med. 2003;115:352–7.

Dauguirdas JT, Blake PG, Todd S. Handbook of dialysis. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2001. Segunda edición española. Barcelona: Masson; 2003. p. 518–44.

Droga GK, Herson H, Hutchison B, Irish AB, Heath CH, Golledge C, et al. Prevention of tunneled hemodialysis catheter-related infections using catheter-restricted filling with gentamicin and citrate: a randomized controlled study. J Am Soc Nephrol 2002;13:2133–9.

García-Rebollo S, Hernández D, Díaz F. Accesos vasculares percutáneos. En: Lorenzo V, Torres A, Hernández D, Ayus JC, editores. Manual de Nefrología. 2nd ed. Madrid: Harcourt; 2002. p. 362–70.

Hamory BH. Nosocomial bloodstream and intravascular device related infections. In: Wenzel RP, editor. Prevention and control of nosocomial infections. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1987. p. 283–319.

Hoen B, Paul Dauphin A, Hestin D, Kessel M (EPIBACDIAL). Multicenter prospective study of risk factor bacteremia in chronic hemodialysis patients. J Am Soc Nephrol 1998;9:869–76.

Jernigan JA, Farr BM. Short-course therapy of catheter-related Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia: a meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med 1993;119:304–11.

Lentino JR, Leehey DJ. Infections. In: Dauguirdas JT, Blake PG, Ing TS, editors. Handbook of dialysis. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2001. p. 495–521.

León C, Castro P. Infección relacionada con catéteres y otros dispositivos intravasculares. Rev Clin Esp 1994;194:853–61.

Levy J, Robson M, Rosenfeld JB. Septicemia and pulmonary embolism complicating use of arteriovenous fistula in maintenance haemodialysis. Lancet 1970;2:288.

Liñares J, Pulido MA, Bouza E. Infección asociada a catéteres. Medicine 1995;76:3395–404.

Martínez M, Maldonado, Rodicio JL, Herrera J. Tratado de Nefrología. Norma: 1993; 1124–5.

Pearson ML. Guideline for prevention of intravascular device-related infections. Part I. Intravascular device-related infections—an overview. The Hospital Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee. Am J Infect Control 1996;24:262–7.

Reed CR, Sessler CN, Glauser FL, Phelan BA. Central venous catheter infections: concepts and controversies. Intensive Care Med 1985;21:177–83.

Rello J, Campistol JM, Almirall J, Revert L. Complicaciones mecánicas e infecciosas asociadas a la cateterización venosa central como acceso vascular para hemodiálisis. Rev Clin Esp 1988;183:455–8.

Rodriguez-Jornet A, Garcia-Garcia M, Mariscal D, Fontanals D, Cortes P, Coll P, et al. Outbreak of gram negative bacteremia especially Enterobacter cloacae, in patients with long term tunnelled haemodialysis catheter. Nefrologia 2003;23:333–43.

Sánchez Sancho M, Ridao N, Valderrabano F. Complicaciones de la hemodiálisis. En: Valderrabano F, editore. Tratado de Hemodiálisis. Barcelona: Médica JIMS; 1999.

Sitges-Serra A, Liñares J, Perez JL, Capell S. Catheter sepsis: the fourth mechanism. J Antimicrob Chemother 1985;15:641-2.

Thiele Umali A, Lorry GR. Stability of antibiotics used for antibiotic-lock treatment of infections of implantable venous devices. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1999;43:2074–6.

Vardhan A, Davies J, Daryanani I, Crowe A, McClelland P. Treatment of haemodialysis catheter related infections. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2002;17:1149–50.

Guideline 7The incidence of bronchopulmonary infections as complications in haemodialysis patients is high and increased because many of these patients already have previous bronchopulmonary conditions together with their renal insufficiency, the most common produced by Gram-positive microorganisms, although it is also necessary to think of Haemophilus, Pseudomonas and Legionella. Empirical treatment should consider these possibilities. For pneumonia acquired in the community Levofloxacin monotherapy is recommended or the combination of beta-lactam (Amoxicillin-Clavulanate or Ceftriaxone) with Azithromycin. For the exacerbation of COPD the same treatment can be applied but if the patient is colonised by Pseudomonas aeruginosa, an active beta-lactam must be used against this pathogen (Ceftazidime, Cefepime, Piperacillin-Tazobactam, Meropenem or Doripenem).

The treatment should be maintained between 10 and 20 days.

It is advisable to recommend the administration of the anti-pneumococcal vaccine to all patients.

ReferencesDauguirdas JT, Blake PG, Todd S. Handbook of dialysis. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2001. Segunda edición española. Barcelona: Masson; 2003. p. 518–44.

Honorato J. Fármacos y diálisis. Dial Traspl 2010;31:47–53.

Índex Farmacològic, 2000. 5th ed. Fundació Institut Català de Farmacologia. Acadèmia de Ciències Mèdiques de Catalunya i Balears.

Levy J, Robson M, Rosenfeld JB. Septicemia and pulmonary embolism complicating use of arteriovenous fistula in maintenance haemodialysis. Lancet 1970;2:288.

Martínez M, Maldonado Rodicio JL, Herrera J. Tratado de Nefrología. Norma; 1993. p. 1124–5.

Mensa J, Gatell JM, Martínez JA, Torres A, Vidal F, Serrano R, et al. Terapéutica antimicrobiana (infecciones en urgencias). 5th ed. Antares; 2005.

Protocols de malalties infeccioses. Servei de Malalties Infeccioses. Hospital Vall d’Hebron. Barcelona: Servei Català de la Salut; 2003.

Samak MJ, Jaber BL. Pulmonary infections mortality among patients with end-stage renal disease. Chest 2001;120:1183–7.

Guideline 8An endocarditis should be considered in the persistence of fever without apparent focality or following an acute process.

70% of the colonisations are produced in the tricuspid valve by S. aureus and Streptococcus viridans, those caused by enterococcus are less frequent. It is most important to demonstrate endocarditis by means of haemocultures and echocardiogram.

ReferencesAmandh U, Kishore R, Ballal HS. Infective endocarditis as a cause of fever in hemodialysis patients. J Assoc Physicians India 2000;48:736–8.

Besnier JM, Choulet P. Modalités et surveillance de l’antibiotherapie des endocardites infectiouses. Rev Prat (Paris) 1998;48:513–8.

Bonhour D, Boibieux A, Pryramond D. Prophylaxie des endocardites infectieuses. Rev Prat (Paris) 1998;48:519–22.

Dauguirdas JT, Blake PG, Todd S. Handbook of dialysis. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2001. Segunda edición española. Barcelona: Masson; 2003. p. 518–44.

Hirakawa N, Tasaki H, Tanako S, Yamasita K, Okazaki M, Nakashima Y, et al. Infective tricuspid valve endocarditis due to abscess of an endogenous arteriovenous fistula in a chronic hemodialysis patient. J UOEH 2004;26:451–60.

Hoen B, Selton-Suty CH, Bequinot I. Crítères diagnostiques des endocardites infectieuses. Rev Prat (Paris) 1998;48:497–501.

Levine DP, Fromm BS, Reddy BR. Slow response to vancomycin or vancomycin plus rifanpim in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus endocarditis. Ann Intern Med 1991;115:674–80.

Maraj S, Jacobs LE, Maraj R, Kotler MN. Bacteremia and infective endocarditis in patients on hemodialysis. Am J Med Sci 2004;327:242–9.

Martínez M, Maldonado, Rodicio JL, Herrera J. Tratado de Nefrología. Norma; 1993. p. 1124–5.

McCarthy JT, Steckelberg JM. Infective endocarditis in patients receiving long-term hemodialysis. Mayo Clin Proc 2000;75:1008–14.

Megran DW. Enterococcal endocarditis. Clin Infect Dis 1992;15:63–71.

Robinson DL, Fowler VG, Secton DJ, Corey RG, Coulon PJ. Bacterial endocarditis in hemodialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis 1997;30:521–4.

Spies C, Madison JR, Schatz IJ. Infective endocarditis in patients with end-stage renal disease: clinical presentation and outcome. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:71–5.

Troprak O, Caglar BU, Bayata S, Yasar H, Tanrisev M, Ersoy R, et al. Severe mitral valve infective endocarditis with widespread septi emboli in a patient with permanent hemodialysis catheter. Amadolu Kardiyol Derg 2004;4:374–5.

Guideline 9Empirical treatment of endocarditis should be carried out according to the SEQ and SEIMC guidelines: daptomycin with a dose of 10mg/kg of body weight. The addition of aminoglycosides or rifampicin may be considered although not until endocarditis has been confirmed.

ReferencesAmandh U, Kishore R, Ballal HS. Infective endocarditis as a cause of fever in hemodialysis patients. J Assoc Physicians India 2000;48:736–8.

Besnier JM, Choulet P. Modalités et surveillance de l’antibiotherapie des endocardites infectiouses. Rev Prat (Paris) 1998;48:513–8.

Bonhour D, Boibieux A, Pryramond D. Prophylaxie des endocardites infectieuses. Rev Prat (Paris) 1998;48:519–22.

Dauguirdas JT, Blake PG, Todd S. Handbook of dialysis. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2001. Segunda edición española. Barcelona: Masson; 2003. p. 518–44.

Hirakawa N, Tasaki H, Tanako S, Yamasita K, Okazaki M, Nakashima Y, et al. Infective tricuspid valve endocarditis due to abscess of an endogenous arteriovenous fistula in a chronic hemodialysis patient. J UOEH 2004;26:451–60.

Fowler, Vance G, et al. Daptomycin versus standard therapy for Bacteremia and Endocarditis caused by Staphylococcus aureus. N Engl J Med 2006.

Gudiol F, Aguado JM, Pascual A, Pujol M, Almirante B, Miró JM, et al. Documento de consenso sobre el tratamiento de la bacteriemia y la endocarditis causada por Staphylococcus aureus resistente a la Meticilina. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin 2009.

Hoen B, Selton-Suty CH, Bequinot I. Crítères diagnostiques des endocardites infectieuses. Rev Prat (Paris) 1998;48:497–501.

Honorato J. Fármacos y diálisis. Dial Traspl 2010;31:47–53.

Levine DP, Fromm BS, Reddy BR. Slow response to vancomycin or vancomycin plus rifanpim in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus endocarditis. Ann Intern Med 1991;115:674–80.

Levine, Donald P, Lamp Kenneth C. Daptomycin in the treatment of patients with infective endocarditis: experience from a registry. Am J Med 2007;120(10A):S28–S33.

Levine, Donald P. Clinical experience with Daptomycin: bacteraemia and endocarditis. J Antimicrob Chemother 2008;49:5046–50.

Maraj S, Jacobs LE, Maraj R, Kotler MN. Bacteremia and infective endocarditis in patients on hemodialysis. Am J Med Sci 2004;327:242–9.

Martínez M, Maldonado Rodicio JL, Herrera J. Tratado de Nefrología. Norma; 1993. p. 1124–5.

McCarthy JT, Steckelberg JM. Infective endocarditis in patients receiving long-term hemodialysis. Mayo Clin Proc 2000;75:1008–14.

Megran DW. Enterococcal endocarditis. Clin Infect Dis 1992;15:63–71.

Mensa J, Barberán P, Llinares P, Picazo JJ, Bouza E, Álvarez Lerma F, et al. Guía de tratamiento de la infección producida por Staphylococcus aureus resistente a Meticilina. Rev Esp Quimioter 2008.

Robinson DL, Fowler VG, Secton DJ, Corey RG, Coulon PJ. Bacterial endocarditis in hemodialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis 1997;30:521–4.

SEQ, SEPAR, SEMES, SEMG, SEMERGEN, SEMI. Tercer documento de consenso sobre el uso de antimicrobianos en la agudización de la enfermedad pulmonar obstructiva crónica. Rev Esp Quimioterap 2007;20:93–105.

Spies C, Madison JR, Schatz IJ. Infective endocarditis in patients with end-stage renal disease: clinical presentation and outcome. Arch Intern Med 2004;164:71–5.

Zalacaín R, Dorca J, Torres A, Bello S, El-Ebiary M, Molinos L, et al. Tratamiento antibiótico empírico inicial de la neumonía adquirida en la comunidad en el paciente adulto inmunocompetente. Rev Esp Quimioterap 2003;16:457–66.

Troprak O, Caglar BU, Bayata S, Yasar H, Tanrisev M, Ersoy R, et al. Severe mitral valve infective endocarditis with widespread septi emboli in a patient with permanent hemodialysis catheter. Amadolu Kardiyol Derg 2004;4:374–5.

Guideline 10The urinary tracts are a source of frequent infection due to these patients' own uro-renal conditions and through the lack of sufficient urinary fluid. Cystitis and pyelonefritis, in general, and prostatitis in males are the most common. Escherichia coli, Proteus, Klebsiella, Enterococcus, Pseudomonas and Serratia are the most predominant. The culture of biological liquids is obligatory (urine and blood).

ReferencesAslan S. Urinary tract infections. In: Wilcox CS, Craig C, editors. Handbook of nephrology and hypertension. 5th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2004. p. 153–60.

Bibb JL, Serville KS, Gibel LJ, Kinne JF, White RE, Hartssome MF, et al. Pyocystis in patients on chronic dialysis. A potentially mis-diagnosed syndrome. Int Urol Nephrol 2002;34:415–8.

Bishop MC. Infections associated with dialysis and transplantation. Curr Opin Urol 2001;11:67–73.

Dauguirdas JT, Blake PG, Todd S. Handbook of dialysis. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2001. Segunda edición española. Barcelona: Masson; 2003. p. 518–44.

Martínez M, Maldonado Rodicio JL, Herrera J. Tratado de Nefrología. Norma; 1993. p. 1124–5.

Nicolle LE. Urinary tract infection: traditional pharmacologie therapies. Dis Mon 2002;49:111–28.

Tolkoff-Rubin NE, Rubin RH. Therapy of urinary tract infection. In: Brady HR, Wilcox CS, editors. Therapy in nephrology and hypertension. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2003. p. 415–23.

Torres A. Infecciones del tracto urinario. En: Lorenzo V, Torres A, Hernández D, Ayus JC, editores. Manual de Nefrología. 2nd ed. Madrid: Harcourt; 2002. p. 67–82.

Guideline 11If the infection is local empirical treatment should be started with second or third generation cephalosporin or amoxicillin-clavulanate.

If the infection is complicated, treatment should be started with ertapenem in order to cover the enterobacterium producers of extended spectrum beta-lactamases (ESBLs) or if P. aeruginosa is suspected, ceftazidim, piperacilina-tazobactam, meropenem or doripenem should be used.

If the infection (urinary) is caused by enterococcus, vancomycin or daptomycin should be considered according to the clinical condition of the patient (immunosuppressive, elderly, diabetics).

The treatment should be continued between 7 and 14 days according to whether the infection is local or complicated and 21 days if there are positive haemocultures.

ReferencesAslan S. Urinary tract infections. In: Wilcox CS, Craig C, editors. Handbook of nephrology and hypertension. 5th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2004. p. 153–60.

Bibb JL, Serville KS, Gibel LJ, Kinne JF, White RE, Hartssome MF, et al. Pyocystis in patients on chronic dialysis. A potentially mis-diagnosed syndrome. Int Urol Nephrol 2002;34:415–8.

Bishop MC. Infections associated with dialysis and transplantation. Curr Opin Urol 2001;11:67–73.

Dauguirdas JT, Blake PG, Todd S. Handbook of dialysis. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2001. Segunda edición española. Barcelona: Masson; 2003. p. 518–44.

Honorato J. Fármacos y diálisis. Dial Traspl 2010;31:47–53.

Martínez M, Maldonado Rodicio JL, Herrera J. Tratado de Nefrología. Norma; 1993. p. 1124–5.

Nicolle LE. Urinary tract infection: traditional pharmacologie therapies. Dis Mon 2002;49:111–28.

Sakoulas George, Golan Yoav, Lamp Kenneth C, Friedrich Lawrence V, Russo Rene. Daptomycin in the treatment of Bacteremia. Am J Med 2007;120:S21–S27.

Tolkoff-Rubin NE, Rubin RH. Therapy of urinary tract infection. In: Brady HR, Wilcox CS, editors. Therapy in nephrology and hypertension. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2003. p. 415–23.

Torres A. Infecciones del tracto urinario. En: Lorenzo V, Torres A, Hernández D, Ayus JC, editores. Manual de Nefrología. 2nd ed. Madrid: Harcourt; 2002. p. 67–82.

Guideline 12Osteoarticular infections usually stem from embolisms of another septic source or from a direct lesion or ulcera in one of the osseous or articulated areas. The germs found may be varied. Therefore we should study and culture the liquid of the affected articulation and the haemocultures. The need for complimentary serological tests should also be assessed.

ReferencesLeonard A, Comty CM, Shapiro FL, Raij L. Osteomyelitis in hemodialysis patients. Ann Intern Med 1973;78:651.

Martínez M, Maldonado Rodicio JL, Herrera J. Tratado de Nefrología. Norma; 1993. p. 1124–5.

Slaughter S, Dworkin RJ, Gilbert DN, Legget JE, Jones S, Bryan TR, et al. Staphylococcus aureus septic artritis in patients on hemodialysis treatment. West J Med 1995;163:128–32.

Valero R, Castañeda O, de Francisco ALM, Piñera L, Rodrigo E, Arias M. Sospecha clínica de osteomielitis vertebral: dolor de espalda en los pacientes con infección asociada a catéter de hemodiálisis. Nefrología 2004;24:583–8.

Guideline 13For empirical purposes, if Gram staining is available and Gram-positive is detected, then treatment with Cloxacillin or first generation cephalosporin is recommended and if penicillin is incompatible, then daptomycin should be used.

If a Gram-negative bacillus is discovered in the Gram staining, treatment with third generation Cephalosporin is recommended.

Vancomycin is not recommended in cases of articular prosthesis infections due to its poor penetration in biofilms and toxicity in prolonged treatment that is required for these infections.

At present daptomycin is the best drug for eliminating biofilms and in animals has proved to be superior compared with vancomycin in prosthesis infections. The treatment should be prolonged for at least four weeks.

ReferencesJohn A-K, Baldoni D, Haschke M, Rentsch K, Schaerli P, Zimmerli W, Trampuz A. Efficacy of Daptomycin in implant-associated infection due to Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA): the importance of combination with Rifampin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2009;53:2719–24.

Leonard A, Comty CM, Shapiro FL, Raij L. Osteomyelitis in hemodialysis patients. Ann Intern Med 1973;78:651.

Martínez M, Maldonado Rodicio JL, Herrera J. Tratado de Nefrología. Norma; 1993. p. 1124–5.

Murillo O, Garrigós C, Pachón ME, Euba G, Verdaguer R, Cabellos C, et al. Efficacy of high doses of daptomycin vs. alternative therapies 1 in experimental foreign-body infection by methicillin-resistant. Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2009;53:4252–7.

Slaughter S, Dworkin RJ, Gilbert DN, Legget JE, Jones S, Bryan TR, et al. Staphylococcus aureus septic artritis in patients on hemodialysis treatment. West J Med 1995;163:128–32.

Valero R, Castañeda O, de Francisco ALM, Piñera L, Rodrigo E, Arias M. Sospecha clínica de osteomielitis vertebral: dolor de espalda en los pacientes con infección asociada a catéter de hemodiálisis. Nefrología 2004;24:583–8.

Guideline 14Intra-abdominal infection is generally produced by enterobacteria, Enterococcus and anaerobic bacteria. The origin is established mainly in a torn hollow viscus and to a lesser percentage by hematogenous tract, bacterial translocation and others.

Infectious complications of the peritoneal dialysis are not included here but are described in detail in Guidelines 18–28.

ReferencesCheung AH, Wong LM. Surgical infections in patients with chronic renal failure. Infect Dis Clin North Am 2001;15:775–96.

Dauguirdas JT, Blake PG, Todd S. Handbook of dialysis. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2001. Segunda edición española. Barcelona: Masson; 2003. p. 518–44.

Honorato J. Fármacos y diálisis. Dial Traspl 2010;31:47–53.

Ito H, Miyagi T, Katsumi T. A renocolic fistula due to colon diverticulitis associated with polycystic kidney. Nippon Hinyokika Gakkai Zasshi. 2004;95:67–70.

Lederman ED, McCoy G, Conti DJ, Lee EC. Diverticulitis and polycystic kidney disease. Am Surg 2000;66:200–3.

Levy MN. Infected aortic pseudoaneurysm following laparoscopic cholecistectomy. Ann Vasc Surg 2001;95:67–70.

McFadden DW, Smith GW. Hemodiaysis associated hemorrhagic cholecystitis. Am J Gastroenterol 1987;82:1081–3.

Guideline 15Once the cultures for identification have been prepared, empirical dosage should be started with Amoxicillin-Clavulanate, third generation Cephalosporin with Metronidazole, Ertapenem, daptomycin, tigecycline or teicoplanin.

In those patients who cannot be treated for enterococcus with either ampicillin or aminoglycoside, the use of daptomycin is recommended. Vancomycin should be avoided due to deterioration of the residual renal function and linezolid due to possible accumulation of unleashed metabolites of lactic acidosis.

The dosage of antibiotics should be modified following an assessment after 48–72h or when the results of the culture are known. For fungal infections due to Candida, Fluconazole should be used or a Candin (Caspofungin, Anidulafungin or Micafungin).

ReferencesCheung AH, Wong LM. Surgical infections in patients with chronic renal failure. Infect Dis Clin North Am 2001;15:775–96.

Dauguirdas JT, Blake PG, Todd S. Handbook of dialysis. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2001. Segunda edición española. Barcelona: Masson; 2003. p. 518–44.

Ito H, Miyagi T, Katsumi T. A renocolic fistula due to colon diverticulitis associated with polycystic kidney. Nippon Hinyokika Gakkai Zasshi 2004;95:67–70.

Lederman ED, McCoy G, Conti DJ, Lee EC. Diverticulitis and polycystic kidney disease. Am Surg 2000;66:200–3.

Levy MN. Infected aortic pseudoaneurysm following laparoscopic cholecistectomy. Ann Vasc Surg 2001;95:67–70.

McFadden DW, Smith GW. Hemodialysis associated hemorrhagic cholecystitis. Am J Gastroenterol 1987;82:1081–3.

Zarate MS, Jorda-Vargas L, Lanza A, et al. Estudio microbiológico de bacteriemias y fungemias en pacientes en hemodiálisis crónica. Rev Argent Microbiol 2005;37:145–9.

Guideline 16Tuberculosis is an infection that still occurs in dialysis patients (10 times superior than in the general population); therefore it would be convenient to carry out a test (PPD), especially in those patients with fever of unknown source, weight loss, desnutrition, less obvious pleural effusion or pulmonary infiltration, adenopathies, ascites or hepatomegalies. Extrapulmonary localisation is frequent. A negative PPD does not exclude it.

ReferencesBelcon MC, Smith EKM, Kahana LM, Shimizu AG. Tuberculosis in dialysis patients. Clin Nephrol 1982;17:14.

Cengiz K. Increased incidence of tuberculosis in patients undergoing hemodialysis. Nephron 1996;73:421–4.

Dauguirdas JT, Blake PG, Todd S. Handbook of dialysis. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2001. Segunda edición española. Barcelona: Masson; 2003. p. 518–44.

Erkoc R, Dogan E, Sayarlioglu H, Etlik O, Tepal C, Calke F, et al. Tuberculosis in dialysis patients, single experience from a endemic area. Int J Clin Pract 2004;58:1115–7.

Fang HC, Lee PT, Chen CL, Wu MJ, Chou KJ, Chung HM. Tuberculosis in patients with end-stage renal disease. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2004;8:92–7.

Martínez M, Maldonado Rodicio JL, Herrera J. Tratado de Nefrología. Norma; 1993. p. 1124–5.

Mensa J, Gatell JM, Martínez JA, Torres A, Vidal F, Serrano R, et al. Terapéutica antimicrobiana (infecciones en urgencias). 5th ed. Antares; 2005.

Treatment of tuberculosis—American Thoracic Society—Medical Specialty Society-Centers for Disease Control and Prevention—Federal Government Agency (US). Infect Dis Soc Am 2003;20:1–7.

Wanters A, Peeterman WF, Vanden Brande P, Demoor B, Evenepoel P, Keuleers M, et al. The value of tuberculin skin testing in haemodialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2004;19:433–8.

Woeltje KF, Mathew A, Rothstein M, Seiler S, Fraser VJ. Tuberculosis infection and anergy in hemodialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis 1998;31:848–52.

Guideline 17The treatment should be administered with the usual dosage: rifampicin, isoniazid and pyrazinamide, adding ethambutol in cases of suspected resistance, during the first 2 months. Isonazid and rifampicin shall be continued afterwards to be completed during 9–12 months.

Rifampicin should always be administered on an empty stomach. Isoniazid and rifampicin require no dose modification in case of renal insufficiency but must be administered after haemodialysis.

In cases of relapse or incomplete previous treatment, a dosage with 4 drugs should be carried out in the first 2 months in case of resistance. It is advisable to add pyridoxine.

The impossibility of using triple therapy in the first 2 months, due to intolerance to one or several of the antibiotics, determines the search for a double combination, which allows it to be maintained during 18 months. The combination of pyrazinamide+levofloxacin would be useful in cases where it is impossible to prescribe rifampicin, isoniazid or ethambutol.

Those patients with a previously negative PPD, who seroconvert in dialysis or who have an induration >10mm, must be prescribed prophylactic treatment during 6 months. It would also be advisable in cases of negative PPD in contact with an active carrier.

ReferencesBelcon MC, Smith EKM, Kahana LM, Shimizu AG. Tuberculosis in dialysis patients. Clin Nephrol 1982;17:14.

Cengiz K. Increased incidence of tuberculosis in patients undergoing hemodialysis. Nephron 1996;73:421–4.

Dauguirdas JT, Blake PG, Todd S. Handbook of dialysis. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2001. Segunda edición española. Barcelona: Masson; 2003. p. 518–44.

Erkoc R, Dogan E, Sayarlioglu H, Etlik O, Tepal C, Calke F, et al. Tuberculosis in dialysis patients, single experience from a endemic area. Int J Clin Pract 2004;58:1115–7.

Fang HC, Lee PT, Chen CL, Wu MJ, Chou KJ, Chung HM. Tuberculosis in patients with end-stage renal disease. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2004;8:92–7.

Honorato J. Fármacos y diálisis. Dial Traspl 2010;31:47–53.

Martínez M, Maldonado Rodicio JL, Herrera J. Tratado de Nefrología. Norma; 1993. p. 1124–5.

Mensa J, Gatell JM, Martínez JA, Torres A, Vidal F, Serrano R, et al. Terapéutica antimicrobiana (infecciones en urgencias). 5th ed. Antares; 2005.

Treatment of tuberculosis—American Thoracic Society–Medical Specialty Society–Centers for Disease Control and Prevention-Federal Government Agency (US). Infect Dis Soc Am 2003;20:1–7.

Wanters A, Peeterman WF, Vanden Brande P, Demoor B, Evenepoel P, Keuleers M, et al. The value of tuberculin skin testing in haemodialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2004;19:433–8.

Woeltje KF, Mathew A, Rothstein M, Seiler S, Fraser VJ. Tuberculosis infection and anergy in hemodialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis 1998;31:848–52.

Peritoneal dialysis (PD)Guideline 18The patient receiving peritoneal dialysis has specific infections: related to the catheter or peritonitis.

Prophylactic measures mentioned in Guideline 1, such as the administration of intravenous antibiotic in the insertion of the catheter, cefazolin or vancomycin1, have to be implemented afterwards with hypertonic saline solution wash of the orifice of the peritoneal catheter. Hydrogen peroxide should be specifically avoided. The search for and treatment of nasal carriers is important.

Guideline 19Infection should be suspected in the case of signs of periorificial flogosis: tumor, blushing, pain and especially sweating (related to the catheter), suspicion of subcutaneous abscess, cloudy peritoneal liquid or abdominal pain (peritonitis) with or without fever.

Guideline 20If an infection of the orifice is suspected (a possibility if there is erythema and certainly if there is purulent secretion), local prophylaxis should be reinforced with washes of hypertonic saline solution and an application of 2% mupirocin cream or gentamicin. If there is no response after 48–72h, it is necessary to use the specific antibiotic for the isolated germ. If biological data are not available, other drugs of a broader spectrum have to be used, such as topical ciprofloxacin or bacitracin until the antibiogram is known. If there is secretion, the treatment should be carried out through systematic administration (table).

Guideline 21If a tunnel infection is suspected (secretion and/or edema and/or pain on touch), normally preceded by infection of the orifice and after proceeding to bacteriological studies, a local and systematic empirical treatment should be administered, initially orally (table), according to the results of the Gram staining of cutaneous smear or the secretion, if this technique were feasible, according to the indications in Guideline 4. The confirmation of the germ and its sensitivity implies changing the treatment if necessary. These treatments should have a minimum duration of 14 days. It is especially important to identify Staphylococcus aureus and/or P. aeruginosa, since the duration of the antibiotic treatment may be prolonged with these germs.

Table 3. Treatment of infection of the orifice/tunnel2

| Name of the antibiotic DCPA | Dosage |

| Amoxicillin | 250–500mg/12h |

| Cephalexin | 500mg/12h |

| Ciprofloxacin | 250–500mg/12h |

| Clarithromycin | 250–500mg/12h |

| Daptomycin | 6mg/kg/day |

| Dicloxacillin | 250–500mg/12h |

| Fluconazole | 200mg/day |

| Isoniazid | 2000mg first day, then 1000mg/day |

| Linezolid | 600mg/12h |

| Metronidazole | 400mg/12h, <50kg |

| 400–500mg/8h, >50kg | |

| Ofloxacin | 400mg first day, then 200mg/day |

| Pyrazinamide | 35mg/kg/day |

| Rifampicin | 450mg/day, <50kg |

| 600mg/day, >50kg | |

| Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole | 80/400mg/day |

The appearance of peritonitis or if the infection remains after 4 weeks implies the withdrawal of the catheter (table).

Guideline 23If peritonitis is suspected (basically a cloudy liquid) and after the cytological assessments (more than 100 cells/ml, with 50% being polymorphonuclear) and bacteriologic (carrying out of culture and recommended Gram staining) of the effluent, intraperitoneal treatment should be administered with vancomycin and a beta-lactam with activity against pseudomonas. Synergic action can be achieved by adding tobramycin.

Gram staining can not only provide bacterial data but also give an early warning of fungi. See dose in table.

Guideline 24When peritoneal infection is confirmed and the germ identified as Gram-positive, the treatment can be adjusted to the sensitivity of the causing agent or vancomycin can be maintained if the response has been favourable.

In the case of Gram-negative confirmation, vancomycin should be withdrawn and the treatment continued with a beta-lactam adequate for sensitivity. If the isolated pathogen is P. aeruginosa, a treatment combined with aminoglycoside is advisable in order to search for synergy. In the case of allergy towards beta-lactams, ciprofloxacin can be used whenever P. aeruginosa is sensitive.

See dose in table.

Guideline 25If peritonitis is confirmed by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and if the empirical response to Vancomycin has not been satisfactory, then the introduction of daptomycin can be considered.

Guideline 26Other recommendations to be taken into account:

• If peritonitis is suspected through anaerobic germs (e.g. perforation), the addition of metronidazole and ampicillin is recommended. However, if it is polymicrobial, then a surgical assessment is advisable.

• In the case of peritonitis in APD, treatment is advised over longer intervals and with larger doses or frequency (table).

Table 4. Antibiotic treatment for peritonitis

Name of antibiotic CAPD Intermittent (1booster shot/day) Continues (load/l) Continuous (maintenance) Amoxicillin ND 250–500 50 Ampicillin ND 125 125 Amikacin 2mg/kg 25 12 Tobramycin or Gentamicin 0.6mg/kg 8 4 Cefazolin or cephalothin 15mg/kg 500 125 Ceftazidime 1000–1500mg 500 125 Cefepime 1000mg 500 125 Ciprofloxacin ND 50 25 Vancomycin 15–30mg/kg every 5–7 days 1000 25 Aztreonam ND 1000 250 Imipenem/cilastatin 1000mg (2booster shots/day) 500 200 Quinupristin-Dalfopristin 25mg/l (alternate booster shots) ND ND Amphotericin B ND ND 1500 Ampicillin-sulbactam 2000/every 12h 1000 100 APD Vancomycin 30mg/kg long perm./3–5 days 15mg/kg lp/3–5 days Cefazolin 20mg/kg lp/days Tobramycin 1.5mg/kg long perm./day 0.5mg/kg lp/day Cefepime 1000mg/day Fluconazole 200mg/day every 24–48h APD: acute PD; CAPD: continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis.

• It is advisable to adjust the dose according to body weight, residual function and also in high transporters.

If fungal peritonitis is confirmed, usually due to Candida, fluconazole or candin should be indicated, separately or together, either through systemic administration or peritoneal and early withdrawal of the catheter should be carried out, although some authors advise waiting 48–72h for a response to the treatment.

Guideline 28In any type of peritonitis a lack of response after 5 days or at most after a week of treatment or a worsening of the condition should indicate the withdrawal of the catheter. In this case, it is advisable to maintain the antibiotic treatment for at least 7 days after withdrawal of the peritoneal catheter.

Common features (HD and PD)Guideline 29Isolation criteria:

• Pulmonary tuberculosis in active phase, during the first 2 weeks of withening treatment.

• Systematic infection or open suppuration due to methicillin-resistant S. aureus. The nasal carriers of this microorganism do not need isolation, but should receive treatment with mupirocin and a strict adherence to all the measures indicated in “Guideline 1”. If there are cutaneous lesions positive to methicillin-resistant S. aureus, these should be protected during the stay in the dialysis unit.

• Patients with acute bronchopulmonary infection due to Acinetobacter and/or Aspergillus.

Mensa J, Gatell JM, Martínez JA, Torres A, Vidal F, Serrano R, et al. Terapéutica antimicrobiana (infecciones en urgencias). 5th ed. Antares; 2005.

Protocols de malalties infeccioses. Servei de Malalties Infeccioses. Hospital Vall d’Hebron. Barcelona: Servei Català de la Salut; 2003.

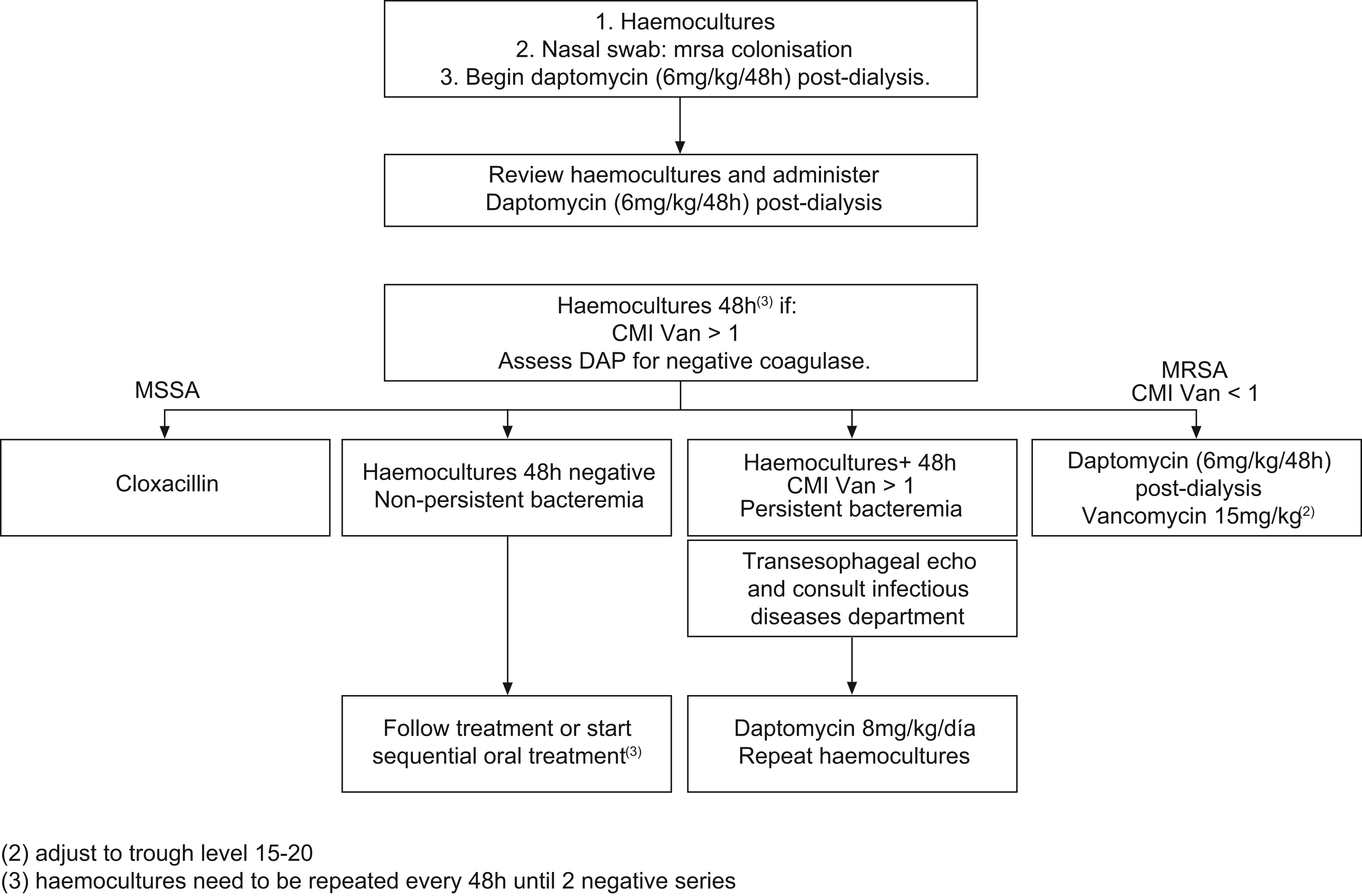

Guideline 30Faced with a situation of acute infection and also in the case of chronic haemodialysis infection (figure), it is necessary to adjust the doses of the following drugs: amoxicillin-clavulanate 500/125/24h, with additional dose after dialysis; aztreonam 1g/24h and 500mg after dialysis; cefazolin 1g/24h and 500mg after dialysis; cefuroxime 750mg/24h intravenous, with additional dose after dialysis; cefuroxime 500mg/24h orally; ceftazidime 500mg/24h, with additional dose after dialysis; ciprofloxacin 500mg/24h, with additional dose after dialysis yet not at the same time as calcium salts or Fe; cloxacillin 2g/8h; ethambutol 15mg/kg/48h, flucytosine 37.5mg/kg/48h; fluconazole 200mg/24h; gentamicin 2mg/kg/48h after dialysis, levofloxacin 500mg initially and 125mg/24h not at the same time as calcium salts or Fe; rifampicin 300mg/24h; vancomycin 1g/week; pyrazinamide no data (assess the need for treatment).

Fig. 2. Patient with chronic renal insufficiency in haemodialysis programme. Medical profile compatible with bacteremia without apparent source.

Guideline 31Due to their own specific toxicity, possible organic or systematic manifestations associated with the anti-infectious treatment must be monitored. Therefore, attention must be paid to:

• beta-lactams—reactions of systemic hypersensitivity, fever;

• cephalosporins—possibility of allergies and occasionally encephalopathy;

• ethambutol—ocular alterations, hyperuricaemia;

• flucytosine and fluconazole—digestive problems, cutaneous reactions, alterations of the central nervous system, elevation of the transaminases, medullar toxicity;

• gentamicin—toxicity of pair VII, the other aminoglycosides are less toxic (tobramycin, amikacin);

• isoniazid—peripheral neuritis (avoidable if pyridoxine is added) hepatotoxicity in the first months;

• linezolid—do not administer with MAOIs, do not give orally to patients with phenylketonuria, neuropathy;

• metronidazole—digestive problems and cutaneous reactions in prolonged treatment (sensitive polyneuritis, encephalopathy, convulsions);

• pyrazinamide—photosensitivity, hepatotoxicity, hyperuricaemia, porphyria;

• quinolone—athralgias, photosensitivity, alterations of the central nervous system;

• rifampicin—ataxia, myopathy, cephalea, photosensitivity, increase of bilirubin, flu syndrome administered intermittently;

• vancomycin—red man syndrome, (skin rash if not administered slowly), reversible leukopenia and thrombocytopenia;

• amphotericin B—pain on intraperitoneal infusion.

Bailie GR. Therapeutic dilemmas in the management of peritonitis. Perit Dial Int 2005;25:152–7.

Doñate T, Borrás M, Coronel F, Lanuza M, González MT, Morey A, et al. Diálisis peritoneal. Consenso de la SEDYT; 2004

Flanigan M, Gokal R. Peritoneal catheters and exit site practices toward optimum peritoneal access: a review of current developments. Perit Dial Int 2005;25:132–9.

Molina A, Ruiz C, Pérez Díaz V, Martín D. Peritonitis especiales: fúngica, tuberculosa, no infecciosa. En: Coronel F, Montenegro J, Selgas R, editores. Manual Práctico de Diálisis Peritoneal. Badalona: Atrium; 2005. p. 165–7.

Montenegro J. Peritonitis bacteriana. En: Coronel F, Montenegro J, Selgas R, editores. Manual Práctico de Diálisis Peritoneal. Badalona: Atrium; 2005. p. 155–60.

Montenegro J, Aguirre R, Ocharán J. Peritonitis fúngica. En: Montenegro J, Olivares J, editores. La diálisis peritoneal. Madrid: Dibe; 1999. p. 341–51.

Piraino B, Bailie GR, Bernardini J, Boeschoten E, Gupta A, Holmes C, et al. Peritoneal dialysis-related infections recommendations: 2005 Update. Perit Dial Int 2005;25:107–31.

Sansone G, Cirugeda A, Bajo MA, Del Peso G, Sánchez Tomero JA, Alegre L, et al. Actualización de protocolos en la práctica clínica de diálisis peritoneal, año 2004. Nefrología. 2004;24: 410–45.

Selgas R, Bajo MA, Del Peso G, Sánchez-Villanueva R, González E. Evidencias aplicables a la práctica clínica en diálisis peritoneal. Dial Traspl 2005;26:137–48.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Received 28 June 2010

Accepted 2 July 2010

Corresponding author. josejulian.ocharancorcuera@osakidetza.net