Diabetes self-management (DSM) is crucial for glycemic control among type-2 diabetic (T2D) people.

MethodThis was a sequential exploratory mixed-method approach to assess whether a health-based coaching program designed to fit the unmet needs of T2D was the best intervention for improving DSM practice. Twenty-eight participants from different backgrounds were involved in phase 1 (Qualitative study) to explore DSM knowledge and practice, any difficulties obstructing such knowledge and practice, and the feasibility of implementing an intervention program nationwide. Sixty patients were recruited for phase 2 (Quasi-experimental study). A health-based coaching program, constructed to fit the unmet needs from phase 1 was implemented among thirty patients in an experimental group. By comparison, 30 patients in the control group received their usual care. Diabetes and DSM knowledge, DSM practice, and health outcomes were measured and compared between the two groups at baseline and after the 12th week of the intervention.

ResultsThe following problems were found: (1) a low perception of susceptibility to and severity of illness, (2) inadequate DSM knowledge and skills, (3) a lack of motivation to perform DSM practice, and (4) social exclusion and feelings of embarrassment. After the implementation of the program among the experimental group, all the variables improved relative to baseline and to the control group.

ConclusionA health-based coaching program can improve DSM knowledge and practice and health outcomes. A nationwide program is recommended to promote DSM practice among Indonesian communities.

El autocontrol de la diabetes (ACD) es crucial para controlar la glucemia en las personas con diabetes de tipo 2 (DT2).

MétodoUn método mixto exploratorio secuencial para valorar si un programa de entrenamiento basado en la salud diseñado para satisfacer las necesidades no cubiertas de la DT2 era la mejor intervención para mejorar la práctica del ACD. Veintiocho participantes desde diferentes puntos de vista participaron en la fase 1 (estudio cualitativo) para explorar el conocimiento y la práctica del ACD, sus obstáculos y la viabilidad de implantar la intervención. Se reclutó a 60 pacientes en la fase 2 (estudio cuasi-experimental). Se implantó un programa de entrenamiento basado en la salud, ideado para satisfacer las necesidades no cubiertas de la fase 1, en 30 pacientes de un grupo experimental. En comparación, se prestó la asistencia habitual a 30 pacientes del grupo de comparación. Se determinaron el conocimiento de la DM y del ACD, la práctica del ACD y los resultados de salud, y se compararon entre los dos grupos en el momento basal y después de la 12a semana de la intervención.

ResultadosSe hallaron varios obstáculos: 1) baja percepción de la predisposición a la enfermedad y de su gravedad, 2) conocimiento del ACD y habilidades para realizarlo insuficientes, 3) falta de motivación para la práctica del ACD y 4) exclusión social y sensación de vergüenza. Tras la implantación en el grupo experimental, se halló mejoría de todas las variables respecto al momento basal, y eran también mejores que en el grupo de comparación.

ConclusiónEl programa de entrenamiento basado en la salud puede mejorar el conocimiento y la práctica del ACD y los resultados de salud. Se recomienda un programa nacional para promover la práctica del ACD en las comunidades indonesias.

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is a worldwide non-communicable disease. In 2016, the World Health Organization estimated that more than 422 million people were affected with DM, and approximately 1.6 million deaths were found1 (World Health Organization factsheets, 2018). Sixty percent of total DM occurred in the Asian region, where an increase of urbanization and socioeconomic transition were the contributing factors.2 According to the total estimates, 87.5% had uncontrolled type 2 DM.3 Indonesia has a prevalence of DM in the adult population of 6.2%, i.e. 10.6 million in 2019. This prevalence was higher in women (7.7%) than in men (6.5%).4 The majority of people with DM in Indonesia were also faced with poor glycemic control and long-term complications.

Poor glycemic control has remained a significant problem among type 2 DM patients. One of the most critical factors for the control and management of DM is diabetes self-management (DSM) practice.5–7 DSM is defined as an individual's ability to manage symptoms and the physical and psychosocial consequences by focusing on lifestyle modification, including dietary control, active physical exercise, medical adherence, on-time blood glucose monitoring, coping with stress, and the prevention of DM complications.8

Regular DSM practice becomes crucial for people with DM to prevent hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia. Hypoglycemia may result in seizures or loss of consciousness.9,10 Hyperglycemia may increase the risk of cognitive impairment and Alzheimer's disease.11 Moreover, sufficient DSM will enhance patients’ health by helping them to avoid severe complications such as retinopathy, nephropathy, and neuropathy, all of which contribute to premature mortality and low quality of life.12,13

A study by Tong et al. demonstrated that competing daily demands, frustration, other forms of emotional distress, and low self-commitment were the critical determinants of poor DSM practice.14 Some recent studies found the following barriers to be associated with poor DSM practices; a low perception of illness, inadequate knowledge and skills regarding DSM practice, insufficient family involvement in support of DSM practice, and social exclusion.5

Previous findings indicated regular DSM practice as an effective strategy for glycemic control among diabetic people.5 A recent study demonstrated that participatory learning through the sharing of ideas and experiences, small group discussion, brainstorming sessions on case studies, role-play, skill-based training, and coaching as an active learning process among adult people could enhance individual behavior.15

Some efforts have been launched in Indonesia to improve glycemic control such as the Prolanis program, which emphasized lifestyle modification by providing diabetes self-management education (DSME).5 However, a preliminary finding found DSME to be ineffective due to insufficient coaching and monitoring from healthcare providers. Poor DSM practice also occurred in West Sulawesi province since most people with DM lacked awareness of the importance of DSM practice. They preferred to eat sweet and fatty food. Moreover, they also lacked skills in performing regular physical activity and blood glucose monitoring as well as in dealing with diabetic complications.

West Sulawesi Province is located in Indonesia's western region, with more than ten ethnic groups having a variety of cultural beliefs and living arrangements.5 Agricultural products for household use in this area are rice, corn, cassava, yams, and coconut. People usually cook at home and meals are shared between people with DM and their family members. The majority of their daily meals are curry with coconut milk. Previous intervention studies related to DSM practice, such as cluster-randomized Control trials and quasi-experimental studies,16–18 did not, in reality, fit the various social and cultural contexts and patient needs in West Sulawesi, Indonesia. Therefore, a suitable solution to fill this gap was to apply a sequential exploratory mixed-method design using both qualitative and quantitative approaches. An application of the exploratory mixed-method design could harness the strengths and counterbalance the weaknesses of both qualitative and quantitative studies.19–21 The unmet needs obtained from the qualitative study were used to guide intervention activities in the later quantitative study. Fruitful findings from this study should be adopted into routine service and scaled-up as a nationwide program to promote DSM practice among people with poor glycemic control to reduce premature death and to increase the quality of life for Indonesian communities in the future.

Study objectivesThe study had two main aims as follows: (1) to explore specific DSM practice and any problems and barriers among uncontrolled T2D people in West Sulawesi; (2) to examine the effectiveness of the health-based coaching program to promote DSM practice and clinical outcomes among people with DM.

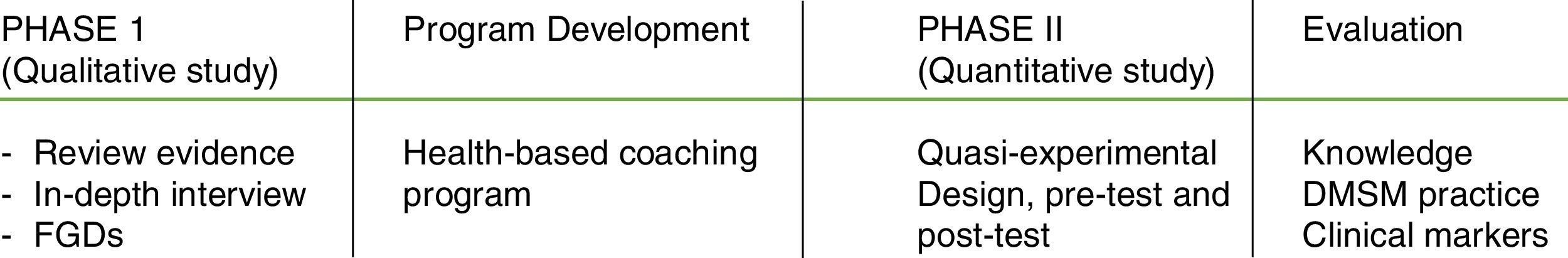

Research methodsA sequential exploratory mixed-method design was applied in this study. It comprised two phases. The first phase was a qualitative study using both in-depth interviews and focus group discussions (FGDs) exploring the current situation, barriers and unmet needs in DSM practice in order to support an appropriate context-specific intervention program that had been extensively and systematically reviewed prior to its contextualisation, based on the first phase. The second phase was a quantitative study using a quasi-experimental design. Details of the study phases are summarized in Fig. 1.

Phase I: Qualitative studyDetails of methods for data collection and key findings from the first phase, as well as how to apply the information to construct a health-based coaching program can be summarized as follows:

Study setting, inclusion & exclusion criteria, and sampling techniqueStudy setting: Two community health centers and two basic health facilities in Polewali Mandar district, West Sulawesi Province, Indonesia, were included as the study settings for conducting in-depth interviews and FGDs from the different viewpoints of key informants. Moreover, a home visit was carried out to obtain more elaborate details among patients and their family members as well as to observe the household environment.

Inclusion & exclusion criteria: In order to obtain valuable information based on the triangulation method,19 four groups of key informants were recruited to share their different viewpoints in the qualitative study. They comprised eight patients with poor glycemic control, eight family members who were the primary carers of patients with type 2 DM, six healthcare providers (HCPs), and six village health volunteers (VHVs). All the participants were directly involved in sharing their experiences and viewpoints on DSM and its barriers and the unmet needs of DM patients. Inclusion criteria were summarized by each group as follows: Firstly, uncontrolled patients who were willing to participate in this study, having lived at least one year in South Sulawesi, with an age ≥35 years old, and HbA1c ≥6.5%. Secondly, carers who stayed with the DM patients and were mainly involved in DSM support. Thirdly, HCPs involved in DSME, routine health check-ups, blood glucose monitoring, prevention complications, home visits, and follow-ups. The last group was VHVs, who assisted HCPs in monitoring patients on regular check-ups, and home visits. Excluded were those who declined to provide information or were absent on the date of data collection.

Sampling technique: Purposive sampling based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria was used to select each group of key informants. Saturated data were obtained from each group until no new themes were found.

Data collection processIn this phase, the researchers conducted both an in-depth interview and FGDs, performing different methods to obtain data from different key informant groups to ensure the method of triangulation in this phase. Details of qualitative data collection were as follows:

In-depth interviewAfter conducting a systematic review of DM self-management and diabetic management interventions, the researchers constructed interview guidelines for qualitative data collection. They conducted in-depth interviews with each patient and family caregiver at the community health centers. In case more information was needed, the researchers asked permission to visit their home for further interviews and observation. The research assistants helped by recording and taking notes during each interview. Focus Group Discussionss among the HCP and VHV groups were conducted separately at the same community health centers by the researchers. The research assistants again helped by taking notes and making audio records.

In this phase, an in-depth interview was conducted among eight patient-carer pairs. The main themes to explore were those regarding DM knowledge, DSM practice and its barriers, and existing diabetic care services. All interviewees were asked open-ended questions (e.g., Do you regularly perform DSM?, What are the barriers to you concerning DSM practice?; What previous programs have been implemented in the community?. All the participants were encouraged to be honest regarding their experience with DSM practice. The data saturation was obtained by reaching sample adequacy and representativeness.

Focus group discussionFocus group discussion was conducted to gather information from six healthcare providers (HCPs) and six village health volunteers (VHVs). The primary purpose of this FGD was to obtain information about the implementation of diabetes self-management education (DSME) and its barriers while implementing DSME at the community health center.

Attendees at the meeting were invited to participate. The researchers provided a brief description of the nature and purpose of the study. After the key informants agreed to participate in this study, they were encouraged to share their experiences while taking care of DM patients. The researchers also asked about the barriers to performing DSM practice. During the discussion, the researchers also explored the existing interventions implemented at community health centers. A digital recorder recorded all this information.

Data analysis of the qualitative studyData were transcribed and translated verbatim from an audio recorder into texts. Content analysis was conducted between two researchers to extract key themes and sub-themes and to elaborate the contexts of DSM practice and its barriers based on the informants’ viewpoints. The initial themes were re-checked by the research team to narrow the key themes of this study. Then, the theme was written up in the draft results section. In the final step of the data analysis, all the research teams agreed to reflect before deciding on the final results of the principal theme.

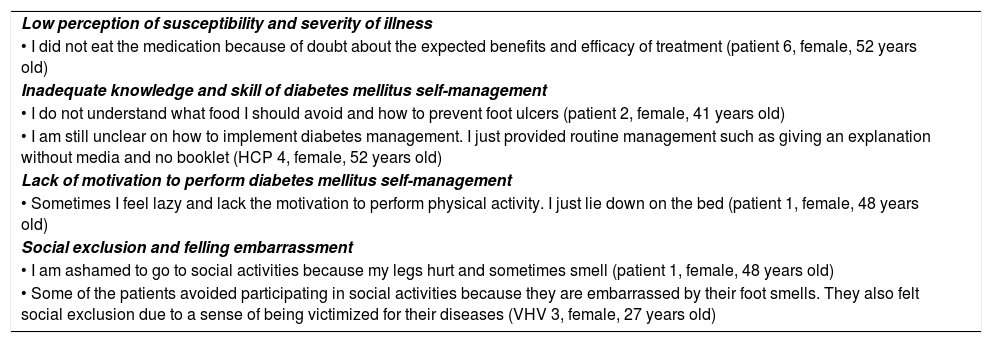

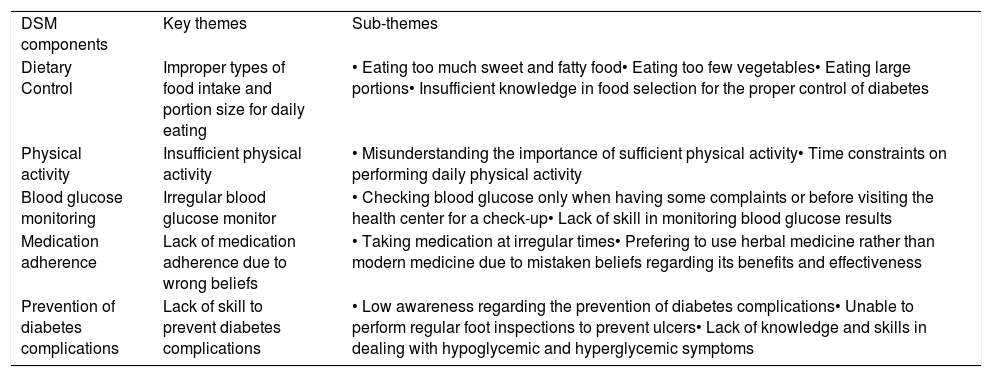

Key findings from the qualitative studyFindings from a qualitative study on key-themes and sub-themes extracted from the different viewpoints of key informants found significant barriers to DSM practices. These were a lack of knowledge regarding DSM, an unfortunate perception of the susceptibility and severity of DM complications, a lack of motivation, poor family support, and felt social exclusion. When considering DSM practice, the findings indicated improper DSM practice among DM patients in all aspects. With regard to dietary control, most of the respondents mentioned difficulties in controlling a healthy diet. They ate food as ordinary people did and never followed the dietary recommendations. They lacked goal setting to manage a healthy diet to prevent hyperglycemia. Many of them ate sweet and fatty food in large portions. Some of them were unaware of the proper kinds of food to eat. Concerning physical activity, most patients did not perform regular physical activity based on the recommendations for DM management, due to time constraints. They misunderstood what proper kinds of physical activity were suitable for diabetic people.

Some patients reported monitoring blood glucose levels only when they found some complaints such as feeling tired or knee pain or before visiting the health center for follow-up. Moreover, most of them seldom bothered to record and track the pattern of blood glucose results themselves. They thought it should be the responsibility of healthcare providers to provide a blood glucose monitor. When considering medication adherence, some favored using herbal medicine instead of modern medicine. The reason was due to a false belief regarding the benefits and effectiveness of such treatment. In addition, some of them did not take diabetic drugs on time due to time constraints when they were working away from home.

Regarding the prevention of complications, most of them had insufficient knowledge of hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia management. In addition, low awareness of diabetic complications and improper skill in foot inspection and care were also included. All details of key themes and sub-themes of barriers to DSM practice and DSM practice are summarized in Tables 1 and 2.

Barriers to diabetes mellitus self-management practice – illustrative quotes from the in-depth interview and focus group discussion among patients, Family caregiver, HCP, and VHV.

| Low perception of susceptibility and severity of illness |

| • I did not eat the medication because of doubt about the expected benefits and efficacy of treatment (patient 6, female, 52 years old) |

| Inadequate knowledge and skill of diabetes mellitus self-management |

| • I do not understand what food I should avoid and how to prevent foot ulcers (patient 2, female, 41 years old) |

| • I am still unclear on how to implement diabetes management. I just provided routine management such as giving an explanation without media and no booklet (HCP 4, female, 52 years old) |

| Lack of motivation to perform diabetes mellitus self-management |

| • Sometimes I feel lazy and lack the motivation to perform physical activity. I just lie down on the bed (patient 1, female, 48 years old) |

| Social exclusion and felling embarrassment |

| • I am ashamed to go to social activities because my legs hurt and sometimes smell (patient 1, female, 48 years old) |

| • Some of the patients avoided participating in social activities because they are embarrassed by their foot smells. They also felt social exclusion due to a sense of being victimized for their diseases (VHV 3, female, 27 years old) |

HCP: Health care provider; VHV: Village health volunteer.

Key themes and sub-themes of problems and barriers to diabetes self-management (DSM) practice obtained from qualitative study in phase I.

| DSM components | Key themes | Sub-themes |

| Dietary Control | Improper types of food intake and portion size for daily eating | • Eating too much sweet and fatty food• Eating too few vegetables• Eating large portions• Insufficient knowledge in food selection for the proper control of diabetes |

| Physical activity | Insufficient physical activity | • Misunderstanding the importance of sufficient physical activity• Time constraints on performing daily physical activity |

| Blood glucose monitoring | Irregular blood glucose monitor | • Checking blood glucose only when having some complaints or before visiting the health center for a check-up• Lack of skill in monitoring blood glucose results |

| Medication adherence | Lack of medication adherence due to wrong beliefs | • Taking medication at irregular times• Prefering to use herbal medicine rather than modern medicine due to mistaken beliefs regarding its benefits and effectiveness |

| Prevention of diabetes complications | Lack of skill to prevent diabetes complications | • Low awareness regarding the prevention of diabetes complications• Unable to perform regular foot inspections to prevent ulcers• Lack of knowledge and skills in dealing with hypoglycemic and hyperglycemic symptoms |

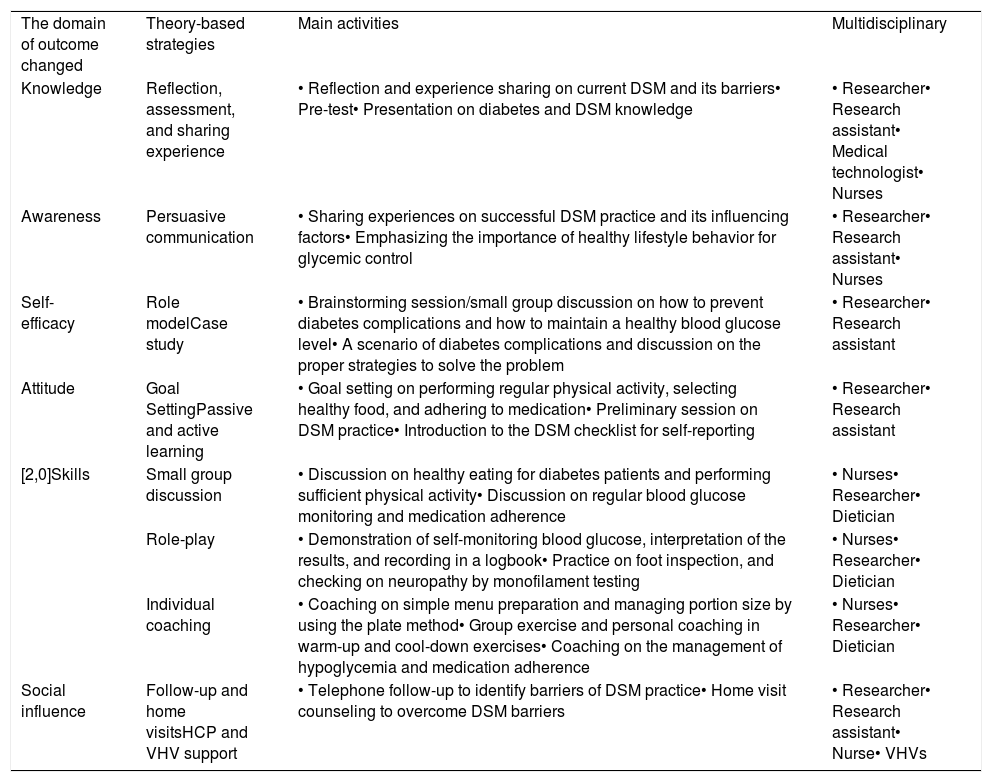

All the information obtained from the qualitative study was used to construct a health-based coaching program. The integrated model of change (I-Changed model)22 was applied to develop a health-based coaching program to improve DSM practice among glycemic uncontrolled T2DM patients. The program consisted of six consecutive domains of outcome changes based on an integration of the theory and the systematic review25 with empirical findings from the qualitative study in the first phase (Table 3).

Health-based coaching program.

| The domain of outcome changed | Theory-based strategies | Main activities | Multidisciplinary |

| Knowledge | Reflection, assessment, and sharing experience | • Reflection and experience sharing on current DSM and its barriers• Pre-test• Presentation on diabetes and DSM knowledge | • Researcher• Research assistant• Medical technologist• Nurses |

| Awareness | Persuasive communication | • Sharing experiences on successful DSM practice and its influencing factors• Emphasizing the importance of healthy lifestyle behavior for glycemic control | • Researcher• Research assistant• Nurses |

| Self-efficacy | Role modelCase study | • Brainstorming session/small group discussion on how to prevent diabetes complications and how to maintain a healthy blood glucose level• A scenario of diabetes complications and discussion on the proper strategies to solve the problem | • Researcher• Research assistant |

| Attitude | Goal SettingPassive and active learning | • Goal setting on performing regular physical activity, selecting healthy food, and adhering to medication• Preliminary session on DSM practice• Introduction to the DSM checklist for self-reporting | • Researcher• Research assistant |

| [2,0]Skills | Small group discussion | • Discussion on healthy eating for diabetes patients and performing sufficient physical activity• Discussion on regular blood glucose monitoring and medication adherence | • Nurses• Researcher• Dietician |

| Role-play | • Demonstration of self-monitoring blood glucose, interpretation of the results, and recording in a logbook• Practice on foot inspection, and checking on neuropathy by monofilament testing | • Nurses• Researcher• Dietician | |

| Individual coaching | • Coaching on simple menu preparation and managing portion size by using the plate method• Group exercise and personal coaching in warm-up and cool-down exercises• Coaching on the management of hypoglycemia and medication adherence | • Nurses• Researcher• Dietician | |

| Social influence | Follow-up and home visitsHCP and VHV support | • Telephone follow-up to identify barriers of DSM practice• Home visit counseling to overcome DSM barriers | • Researcher• Research assistant• Nurse• VHVs |

The development of a healthy-based coaching program has several specific objectives: enhancing DM knowledge on DSM practice, raising awareness of the importance of healthy lifestyle behavior, and enhancing self-efficacy and skill build-up on DSM. Moreover, goal setting regarding regular DSM practice as well as social influence resulting from follow-up and home visits were emphasized. The program was for 12 weeks with 45–60min for each participant per session.

Reflecting on, assessing, and sharing experiences of diabetes management and its problems. The ultimate goal of these activities was to reflect on the current situation of patient behavior, and barriers to and problems of DSM practice. In this study, researchers assessed the baseline data and reflected on the current behavior of diabetic patients. This strategy helped the researchers to construct further interventions better suited for them.

Experience sharing regarding DM management and the problems of DM management was conducted to improve ability and to build positive relationships between the patients and their family members as well as with the HCPs. Each participant shared their experiences in sessions of 45min.

Small group discussions on DSM practice. The ultimate goal of a small group discussion was to encourage active learning, and to develop critical thinking, positive communication, problem solving, and decision making skills. The study found a lack of communication on DSM or patients’ conditions among patients and family members, a discouragement of patients’ problems and a refusal to share problems. These findings led researchers to construct the small group discussion to achieve target goals and to encourage active learning on education processes and to build-up critical thinking when faced with DSM problems.

Brainstorming and group discussion. The ultimate goal of brainstorming and group discussion is to generate ideas within a group discussion. In this study it was found that some patients faced several barriers to implementing the DSM program. They found it difficult to control their diet and forgot to take medication when away from home. A lack of awareness of the patient's condition and a negative expression of the patient's condition were also found among family members. Using brainstorming and group discussion on the importance of family members in DSM practice and explaining the roles of family members in DSM practice are an essential way to facilitate creative group decision making and the key to success in DSM practice.

Goal setting in DSM practice. The ultimate goal of this activity is to provide direction and to promote action toward goal-related DSM activities. Results from this study found that DSM patients and their caregivers performed their daily routines without target setting. Misconception and a lack of communication in terms of DSM practice among them were also found from the qualitative findings, such as a lack of blood glucose monitoring, not adhering to medication on time and difficulties in maintaining a healthy diet. Goal setting is fundamental and it is necessary to prioritize which activities should be done first.

Individual coaching on DSM practice. The ultimate goal of individual coaching on DSM practice focused on solutions to increase personal learning and development. Researchers developed an individual intervention to coach patients in creating a simple menu for DM, managing the portion size by using the plate method, hand portions, and how to read food labels. These strategies were constructed since the key qualitative findings reported that most patients mostly ate sweet and fatty food, tended to eat food in large portions and did not control food composition. Other key findings were that some patients were confused regarding physical activity for DM patients, lacked blood glucose monitoring, and did not record blood glucose results or difficult to manage hypoglycemic complications. Using individual coaching on physical activity and warm-up and cooling down exercises after performing physical activity; coaching on how to manage hypoglycemia as well as coaching on how to perform a self-report on medication adherence improved patients’ and families’ ability to achieve the goals and obtain solutions when faced with these problems.

Role-play on self-monitoring blood glucose and identifying diabetes complications. The ultimate goal of the role-play technique used in this study was to encourage practice skills and to assist patients to naturally improve and use their cognitive ability and skills in DM self-monitoring and preventing DM complications. The key findings of the qualitative study reported that most DM patients did not understand DM complications or how to prevent them. Moreover, it was also found that they also lacked regular blood glucose monitoring, which was done only when they were faced with some complaint. By using the role-play method, researchers demonstrated how to self-monitor blood glucose by using a simple tool kit, and how to record the results in the logbook. To monitor the risk of neuropathy, researchers also demonstrated how to perform foot inspection, and check neuropathy using a monofilament test. This strategy improved patients’ and families’ ability to prevent diabetic complications.

Follow-up and home visits. Follow-up and home visits are fundamental strategies to ensure that patients and their families are going ahead with the prescribed management plan, such as undergoing testing and taking medication. Moreover, to improve the likelihood of positive outcomes, follow-up and home visits are critical for minimizing safety concerns. Home visits also help family members to build strong relationships with the patients. In this study researchers conducted telephone calls for regular follow-up and went to villages for home visits to identify any barriers to DSM practice and to prevent the possibility of DSM barriers with the patients and their families.

Phase II quantitative studyStudy design and samplesA quasi-experimental study, pre-test, and post-test design with a non-equivalent control group was conducted to examine the effectiveness of a health-based coaching program on DSM practice and health outcomes in terms of biological markers among uncontrolled T2D people.

Sixty T2D people were selected based on the inclusion criteria and were randomly allocated into the experimental group and the comparison group using a lottery sampling method. The inclusion criteria were: (1) glycemic uncontrolled with HbA1c level equal or more than 6.5%, (2) a native speaker in the Indonesian language, (3) aged between 35 and 59 years, (4) without severe complications requiring hospitalization. Both groups had similar socio-cultural backgrounds and had resided in similar geographical areas for at least one year.

Data collection procedureThe instrument for data collection comprised: (1) a self-administered questionnaire with two parts included as socio-demographic and health information (SDHI), DM and DSM knowledge,23 and DSM practice construction based on a DM self-management questionnaire (DSMQ)24; (2) a recording form to collect information on biological markers obtained from the patient's profile at the community health center.

The DM and DSM knowledge section comprised 10 items of true, false, and not sure answers. The score was=1 for a correct answer, while the rest were=0. The total scores ranged between 0 and 10 and were classified into 3 groups as poor (less than 60% of the total score or less than 6); fair (between 60 and 79% of the total score or equal to 6–7) and good (equal or more than 80% of the total score or equal or more than 8).

The DSM questionnaire (DSMQ) consisted of five dimensions, including diet (4 items), physical activity (3 items), blood glucose monitoring (4 items), medication adherence (2 items), and complication prevention (3 items). The DSMQ was adapted from a previous study of Pamungkas et al.3 Each item score was ranged between 0 and 3 as follows; 0=not at all, 1=sometimes, 2=often, and 3=regularly. Total scores ranged between 16 and 48 and were classified into 3 groups as poor (less than 36), fair (36–42), and good (more than 42) DSM practice.

Validity and reliability test of the questionnaireThe questionnaire was examined for content and construct validity by three experts in the field of non-communicable diseases comprising one doctor, one professor, and one nursing professor. It was translated into the local Indonesian language and translated back by the same native speaker who knows the local language well. It was pilot tested among 30 respondents in a nearby district to determine its reliability. The reliability test results using Cronbach's Alpha coefficient on DSM knowledge was 0.84, and DSM practice was 0.84, respectively. Some words were changed according to the local language to make it easier for respondents to understand and respond.

The researchers, with four trained research assistants from the fourth-year student nurses, joined data collection by interviewing each patient in both groups. The blood test was done at each community health center in both intervention and control groups at baseline and the twelfth week after the program was conducted. The patient's profile was also obtained from each health center to clarify each patient's medical history. The researchers and research assistants implemented the eight-week program. During the home visit, both local healthcare providers and village health volunteers were accompanied to each patient's home.

Data analysis for quantitative studyThis phase aimed to examine the differences between mean scores on DM and DSM knowledge, DSM practice, and biological markers before and after program implementation within the experimental group. Moreover, all mean scores between the experimental and the comparison group after implementation were also compared. A paired t-test was used to examine the differences within the experimental group, while an independent t-test was used to compare the differences between the two groups. The level of statistical test was p<0.05.

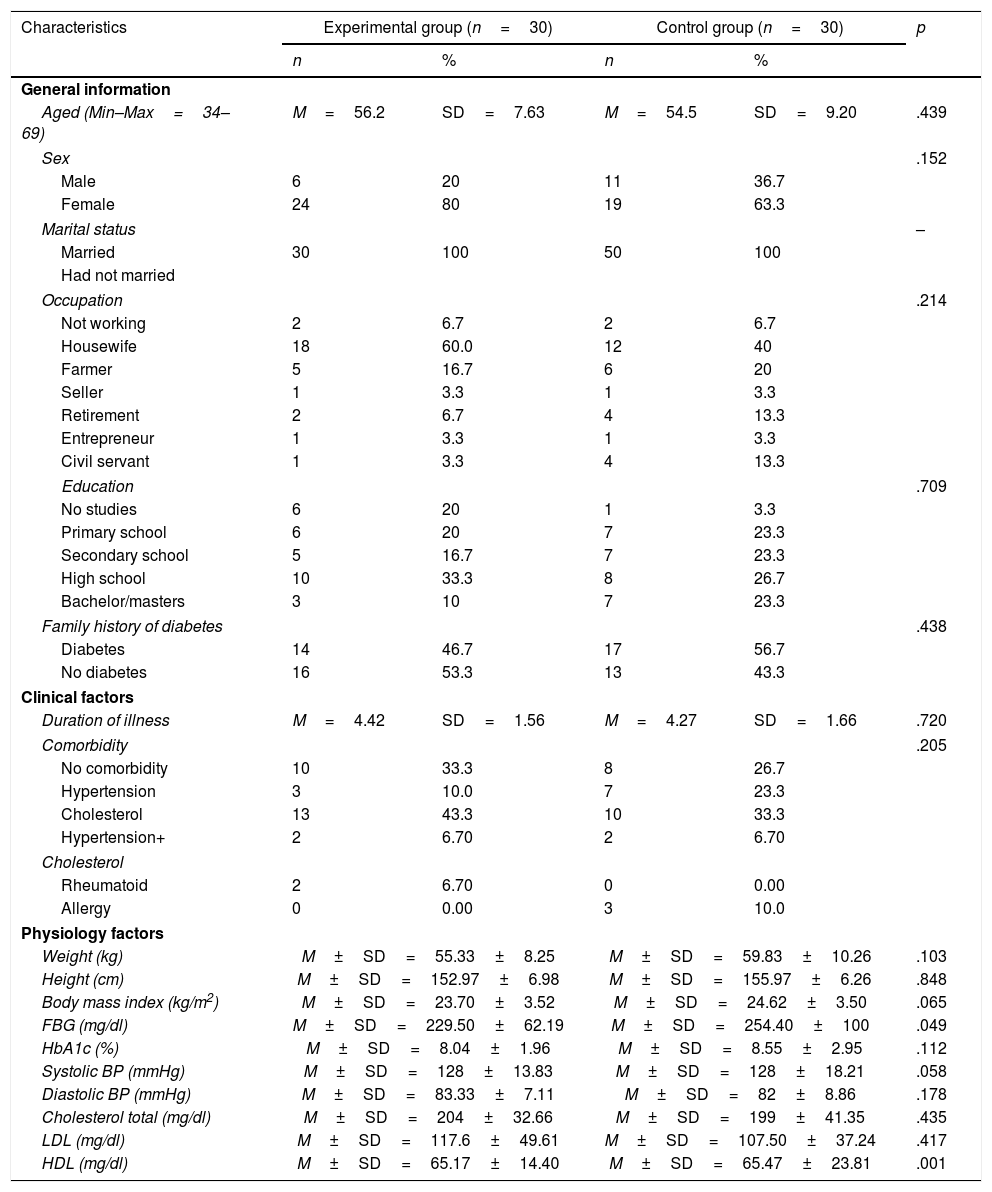

ResultsComparison of socio-demographic and health informationFrom Table 4.1, it can be seen that socio-demographic and health information between the experimental and the comparison group was not significantly different regarding age, sex, marital status, occupation, educational background, or a family history of DM. As to clinical factors and biological markers; there were also no significant differences between the two groups. Finally, behavioral factors were not significantly different between the experimental and the comparison group (p-value >0.05).

Comparison of demographic and health information between the experimental and the control group (N=60).

| Characteristics | Experimental group (n=30) | Control group (n=30) | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | ||

| General information | |||||

| Aged (Min–Max=34–69) | M=56.2 | SD=7.63 | M=54.5 | SD=9.20 | .439 |

| Sex | .152 | ||||

| Male | 6 | 20 | 11 | 36.7 | |

| Female | 24 | 80 | 19 | 63.3 | |

| Marital status | – | ||||

| Married | 30 | 100 | 50 | 100 | |

| Had not married | |||||

| Occupation | .214 | ||||

| Not working | 2 | 6.7 | 2 | 6.7 | |

| Housewife | 18 | 60.0 | 12 | 40 | |

| Farmer | 5 | 16.7 | 6 | 20 | |

| Seller | 1 | 3.3 | 1 | 3.3 | |

| Retirement | 2 | 6.7 | 4 | 13.3 | |

| Entrepreneur | 1 | 3.3 | 1 | 3.3 | |

| Civil servant | 1 | 3.3 | 4 | 13.3 | |

| Education | .709 | ||||

| No studies | 6 | 20 | 1 | 3.3 | |

| Primary school | 6 | 20 | 7 | 23.3 | |

| Secondary school | 5 | 16.7 | 7 | 23.3 | |

| High school | 10 | 33.3 | 8 | 26.7 | |

| Bachelor/masters | 3 | 10 | 7 | 23.3 | |

| Family history of diabetes | .438 | ||||

| Diabetes | 14 | 46.7 | 17 | 56.7 | |

| No diabetes | 16 | 53.3 | 13 | 43.3 | |

| Clinical factors | |||||

| Duration of illness | M=4.42 | SD=1.56 | M=4.27 | SD=1.66 | .720 |

| Comorbidity | .205 | ||||

| No comorbidity | 10 | 33.3 | 8 | 26.7 | |

| Hypertension | 3 | 10.0 | 7 | 23.3 | |

| Cholesterol | 13 | 43.3 | 10 | 33.3 | |

| Hypertension+ | 2 | 6.70 | 2 | 6.70 | |

| Cholesterol | |||||

| Rheumatoid | 2 | 6.70 | 0 | 0.00 | |

| Allergy | 0 | 0.00 | 3 | 10.0 | |

| Physiology factors | |||||

| Weight (kg) | M±SD=55.33±8.25 | M±SD=59.83±10.26 | .103 | ||

| Height (cm) | M±SD=152.97±6.98 | M±SD=155.97±6.26 | .848 | ||

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | M±SD=23.70±3.52 | M±SD=24.62±3.50 | .065 | ||

| FBG (mg/dl) | M±SD=229.50±62.19 | M±SD=254.40±100 | .049 | ||

| HbA1c (%) | M±SD=8.04±1.96 | M±SD=8.55±2.95 | .112 | ||

| Systolic BP (mmHg) | M±SD=128±13.83 | M±SD=128±18.21 | .058 | ||

| Diastolic BP (mmHg) | M±SD=83.33±7.11 | M±SD=82±8.86 | .178 | ||

| Cholesterol total (mg/dl) | M±SD=204±32.66 | M±SD=199±41.35 | .435 | ||

| LDL (mg/dl) | M±SD=117.6±49.61 | M±SD=107.50±37.24 | .417 | ||

| HDL (mg/dl) | M±SD=65.17±14.40 | M±SD=65.47±23.81 | .001 | ||

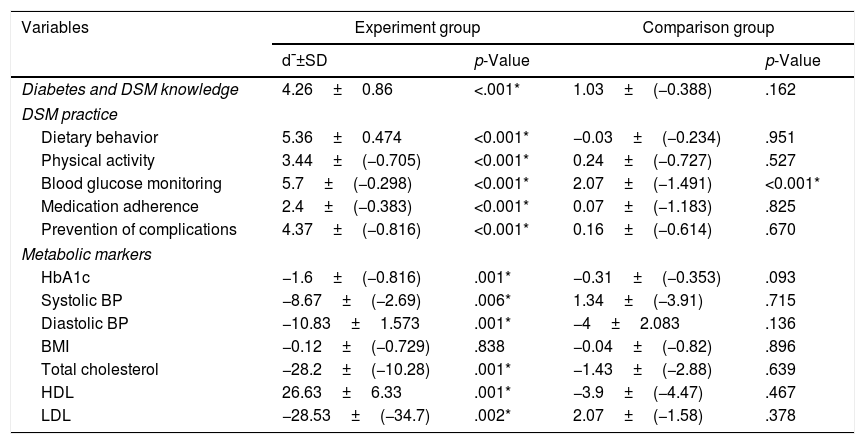

The findings found the mean scores to be different within the experimental group. After implementation of all aspects of DM and DSM knowledge, DSM practice, and metabolic markers were significantly higher than before implementation (p<0.05), except for the BMI, which was not found to be significant. Among the comparison group, the mean scores after implementation in almost all aspects were not significantly higher than before implementation (p>0.05), except for blood glucose monitoring (Table 4.2).

Comparison of mean scores (after–before) on DSM knowledge, DSM practice, and biological markers within the experimental group and the comparison group.

| Variables | Experiment group | Comparison group | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| d¯±SD | p-Value | p-Value | ||

| Diabetes and DSM knowledge | 4.26±0.86 | <.001* | 1.03±(−0.388) | .162 |

| DSM practice | ||||

| Dietary behavior | 5.36±0.474 | <0.001* | −0.03±(−0.234) | .951 |

| Physical activity | 3.44±(−0.705) | <0.001* | 0.24±(−0.727) | .527 |

| Blood glucose monitoring | 5.7±(−0.298) | <0.001* | 2.07±(−1.491) | <0.001* |

| Medication adherence | 2.4±(−0.383) | <0.001* | 0.07±(−1.183) | .825 |

| Prevention of complications | 4.37±(−0.816) | <0.001* | 0.16±(−0.614) | .670 |

| Metabolic markers | ||||

| HbA1c | −1.6±(−0.816) | .001* | −0.31±(−0.353) | .093 |

| Systolic BP | −8.67±(−2.69) | .006* | 1.34±(−3.91) | .715 |

| Diastolic BP | −10.83±1.573 | .001* | −4±2.083 | .136 |

| BMI | −0.12±(−0.729) | .838 | −0.04±(−0.82) | .896 |

| Total cholesterol | −28.2±(−10.28) | .001* | −1.43±(−2.88) | .639 |

| HDL | 26.63±6.33 | .001* | −3.9±(−4.47) | .467 |

| LDL | −28.53±(−34.7) | .002* | 2.07±(−1.58) | .378 |

DSM: Diabetes self-management; HbA1c: Hemoglobin A1c; BP: Blood pressure; BMI: Body mass index; HDL: High-density lipoprotein; LDL: Low-density lipoprotein.

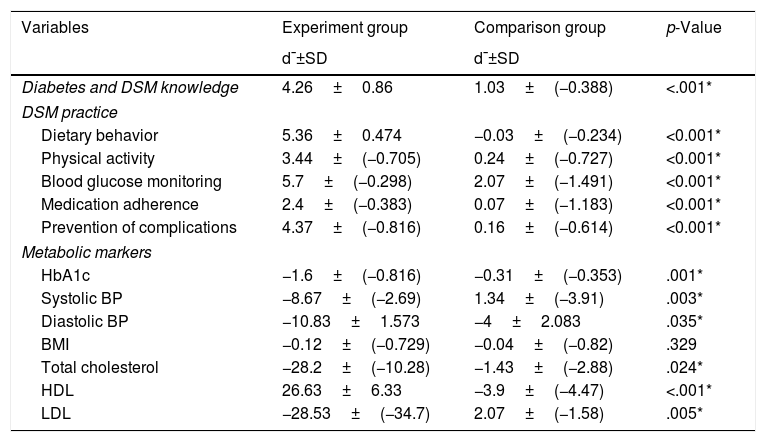

When compared, the mean scores of changes (after-before) regarding DSM knowledge, DSM practice, and biological markers between the experimental group and the comparison group showed significant differences in all aspects (p-value <0.05), as can be seen in Table 4.3.

Comparison of mean scores of changes (after–before) on DSM knowledge, DSM practice, and biological markers between the experimental group and the comparison group.

| Variables | Experiment group | Comparison group | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| d¯±SD | d¯±SD | ||

| Diabetes and DSM knowledge | 4.26±0.86 | 1.03±(−0.388) | <.001* |

| DSM practice | |||

| Dietary behavior | 5.36±0.474 | −0.03±(−0.234) | <0.001* |

| Physical activity | 3.44±(−0.705) | 0.24±(−0.727) | <0.001* |

| Blood glucose monitoring | 5.7±(−0.298) | 2.07±(−1.491) | <0.001* |

| Medication adherence | 2.4±(−0.383) | 0.07±(−1.183) | <0.001* |

| Prevention of complications | 4.37±(−0.816) | 0.16±(−0.614) | <0.001* |

| Metabolic markers | |||

| HbA1c | −1.6±(−0.816) | −0.31±(−0.353) | .001* |

| Systolic BP | −8.67±(−2.69) | 1.34±(−3.91) | .003* |

| Diastolic BP | −10.83±1.573 | −4±2.083 | .035* |

| BMI | −0.12±(−0.729) | −0.04±(−0.82) | .329 |

| Total cholesterol | −28.2±(−10.28) | −1.43±(−2.88) | .024* |

| HDL | 26.63±6.33 | −3.9±(−4.47) | <.001* |

| LDL | −28.53±(−34.7) | 2.07±(−1.58) | .005* |

DSM: Diabetes self-management; HbA1c: Hemoglobin A1c; BP: Blood pressure; BMI: Body mass index; HDL: High-density lipoprotein; LDL: Low-density lipoprotein.

This paper represents a sequential exploratory mixed method design to develop and implement a health-based coaching program to enhance DSM practice among uncontrolled T2DM patients. A combination of two phases of data collection can ensure suitable intervention strategies compatable with local contexts of DM in the Indonesian community. An application of the exploratory mixed-method design can harness the strengths and counterbalance the weaknesses of both quantitative and qualitative studies.25 A qualitative design was used to elicit in-depth information regarding DSM practice and its barriers among T2D patients in DSM practice. Moreover, a systematic review of related kinds of literature, both international and local studies, to elicit preliminary information to be combined with data obtained from a qualitative study using triangulation techniques can be used for the appropriate development of the program contents.26

An application of the integrated model of change (I-change model) guided us to develop a health-based coaching program for the unmet needs in glycemic control among T2D patients. The model is widely used for behavioral change modification by supporting an intervention strategy for unmet needs in healthy behavior.27,28 Therefore, the program fits the local contexts of the Indonesian community and can be applied as a wide-ranging program in other communities with cultural backgrounds similar to those in Indonesia.

This model facilitated active learning experiences among patients through the sharing of ideas, brainstorming, goal setting, individual coaching, role-play, and practicing skills in DSM. Several studies have demonstrated that this learning experience is the most effective learning style for adults.29,30

The combination of raising awareness and enhancing positive attitudes should help T2D people in goal setting and support their self-efficacy in maintaining effective DSM practice for controlling their blood sugar. Previous studies support our findings with similar ways of blending these strategies to improve healthy behavior.31 We also encouraged the patients’ active involvement in the learning process, with group discussion to enhance knowledge, skill, and self-confidence in DSM practice. It has been demonstrated that participatory learning experiences are effective strategies for assisting patients and carers to adopt healthy behavior and promote effective day-to-day living. A systematic review study recommended applying a combination of DSME strategies to improve patient skills in DSM practice and self-awareness among people with DM.32

This study has several strengths because we used a sequential exploratory mixed-method design with two phases. Firstly, a systematic review of theoretically based previous studies was combined with a contextual analysis from the qualitative research to deliver fruitful information to tailor our intervention program in the second phase. Secondly, stakeholder involvement from different viewpoints such as T2DM patients, their families, HCPs, and VHVs provided a basis of diversity for constructing appropriate program activities to deal with DSM practice. Lastly, changes resulting from the implementation of the health-based coaching program could be maintained even after the program was terminated. Our learning process aims to strengthen T2D patients on DSM practice by raising awareness, changing attitudes, and increasing self-efficacy and skills in managing blood glucose.

Some limitations should also be noted, such as that the program was conducted within twelve weeks, which might not have been enough time for evaluating long-term behavioral changes and clinical outcomes, especially BMI status. Moreover, DSM practice among DM patients could not be directly observed. Therefore, the results obtained from a self-administered questionnaire may have been subjective to bias.

Further studies should emphasize participatory action research by involving patients, family members, and communities in the design of intervention strategies to fit with the community context. A longitudinal study should be conducted for continuous follow-up of DSM practice among T2D patients for at least 2–3 years to verify changes in health outcomes, especially the BMI and HbA1c levels. The program is effective in improving DSM practice and health outcomes among the DM group. It should be implemented as a wide-range program in different communities. Before applying for the program, family members, and VHVs or key community leaders should understand their roles in DSM practice to avoid difficulties during program implementation.

ConclusionThis present study was a sequential exploratory mixed-method to develop and implement a health-based coaching program for improving DSM practice and metabolic markers for uncontrolled T2DM. The qualitative study found four barriers to DSM: (1) a low perception of susceptibility and severity of illness, (2) inadequate DSM knowledge and skills, (3) a lack of motivation to perform DSM practice, and (4) social exclusion and feelings of embarrassment. In the quantitative study we also showed that DM knowledge, DSM practice, and metabolic markers were improved from baseline and better than the comparison group after implementation of the health-based coaching program. Therefore, the health-based coaching program can be considered practical and feasible for implementation among uncontrolled T2D subjects in every health setting in Indonesia.

Ethical considerationThe Ethical Review Board, Faculty of Public Health, Mahidol University approved the study (IRB number: MUPH 2018-173). Informed consent was obtained from each participant who was willing to participate in this study.

Authors’ contributionsRA and KC designed the research, analyzed the data, and wrote the paper. PC and PV advised on this study.

Conflict of interestWe declare no conflict of interest in this study. The funding sponsor also had no role in the writing of the manuscript or the decision to publish this manuscript.

The authors would like to thanks the Indonesia Endowment Fund for Education (LPDP Scholarship) for providing a grant for this study. We also thank the patients and staff from community health centers in Polewali Mandar district for valuable information regarding DM management.