Central diabetes insipidus (CDI) is a disease caused by a decrease in or the absence of antidiuretic hormone (ADH) or arginine vasopressin (AVP), characterised by polydipsia and polyuria with hypotonic urine emission.1 Possible causes include neoplasms, such as germinomas or craniopharyngiomas, accidental trauma or trauma secondary to intracranial surgery, midline malformations, diseases caused by accumulations such as sarcoidosis and autoimmune and/or infiltrative diseases such as Langerhans cell histiocytosis.2 There are cases in which there are underlying genetic defects in AVP synthesis, while in others the cause is not fully understood and may be related to an autoimmune component.3 The diagnosis of CDI represents a major challenge in clinical practice, and the water deprivation test (WDT) or thirst test is the standard for diagnosis. However, the test is complex and the results are sometimes inaccurate, so new tools have been developed in recent years, such as measuring arginine- or hypertonic saline-stimulated copeptin.4,5

Extranodal natural killer (NK)/T-cell lymphoma, nasal type (ENKL-NT) is a subtype of lymphoma whose aetiology is not fully understood. It is related to the Epstein–Barr virus (EBV), detection of which is a requirement for diagnosis. It is more common in Asia and America than in the West, it predominates in 40–80-year-old men and affects the nasal area in 80% of cases, presenting with symptoms of nasal obstruction. The definitive diagnosis is histopathological. The treatment of choice is radiotherapy (RT) combined with chemotherapy (CT) in different regimens. The disease has a poor short-to-medium-term prognosis.

We present the case of a 52-year-old male with no known allergies. He was a smoker, with a history of pneumothorax in 2001. One week before admission, he consulted for acute low-back pain, for which he was given an intramuscular injection of 40 mg of methylprednisolone. Three days later, he went to Accident and Emergency complaining of polydipsia and polyuria of seven litres a day, with intermittent paraesthesia on the right side of his face and bilateral nasal congestion. Chest X-ray showed no abnormalities. He was admitted to endocrinology, where a WDT was consistent with the diagnosis of partial CDI (urinary osmolarity of 97 mOsm/kg, which increased after administration of desmopressin >100% up to 535 mOsm/kg), for which treatment was started with desmopressin, 60 mcg/day, at night. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the pituitary showed an increase in the stalk and the pituitary gland itself, with absence of physiological enhancement of the posterior pituitary on T1, and no evidence of tumour-type lesions. Computed tomography (CT) of neck and chest revealed no significant lymphadenopathy suspicious for sarcoidosis.

The patient’s nasal congestion worsened, requiring assessment by Ear, Nose and Throat, who only observed bilateral mucosal thickening with a deviation of the nasal septum. During the first few days of his admission, his low-back pain worsened. A lumbar spine X-ray and lumbar MRI were performed without significant findings. Also performed were a bone series, showing no osteolytic lesions and a blood test for c-ANCA, p-ANCA, anti-cardiolipin Ab, ENA, ANA, anti-DNA Ab, which was negative. Angiotensin-converting enzyme, IgG4 immunoglobulin, alpha-foetoprotein, and human chorionic gonadotropin levels were all normal. The QuantiFERON® test for M. tuberculosis was negative, as were serology for human immunodeficiency virus and hepatitis C and B viruses, PCR for SARS-CoV-2, and the serological diagnoses of syphilis and Lyme disease. Urinary sediment was normal. While the patient was in hospital, several skin lesions appeared in the form of non-pruritic erythematous macule-papules, and Dermatology took a biopsy. The paraesthesia rapidly worsened, extending to the lower limbs with no clear metameric distribution. Neurology carried out a lumbar puncture (LP), with flow cytometry revealing a 66% infiltration of NK cells, findings consistent with the preliminary results of the skin biopsy. At that point the patient was transferred to Haematology.

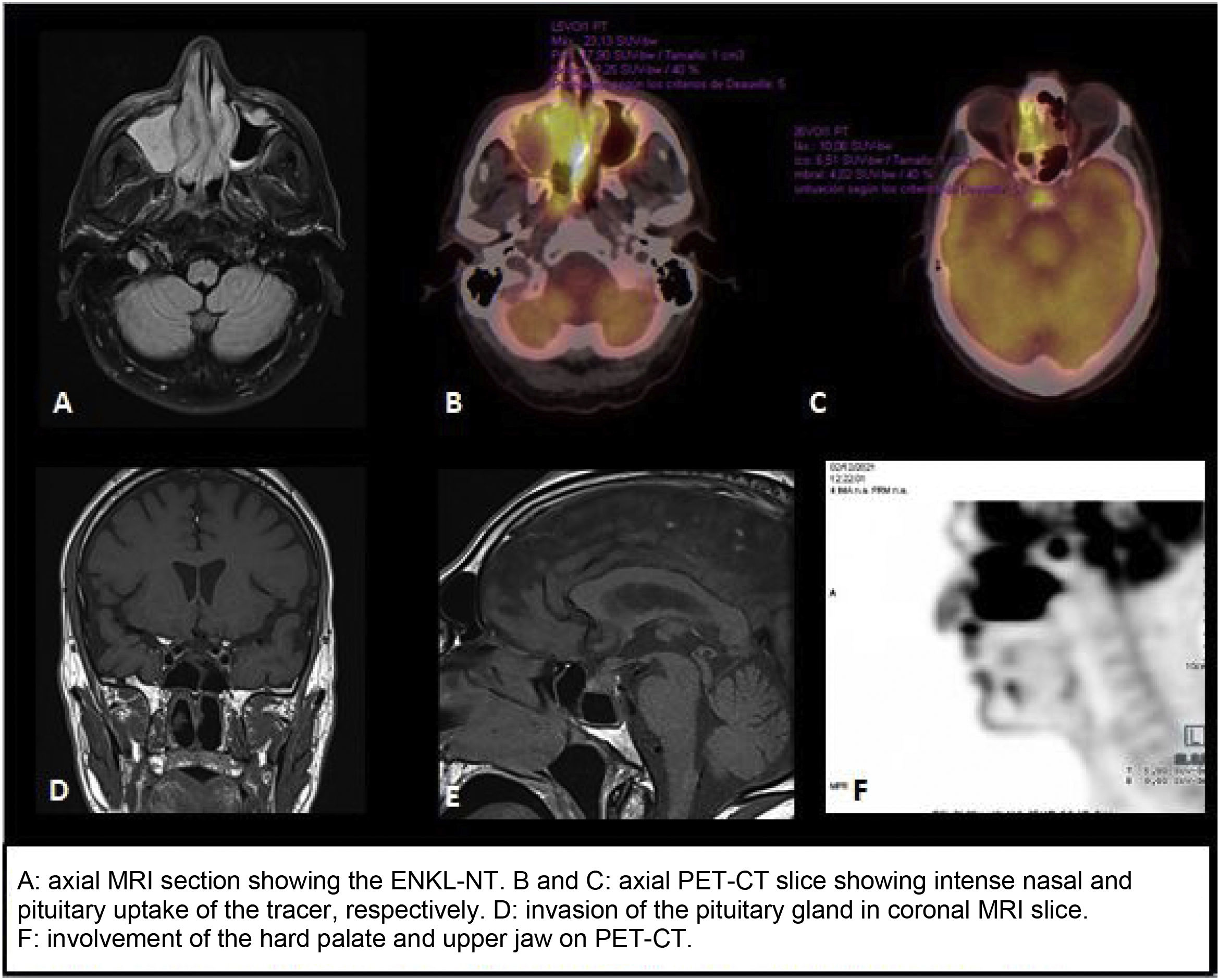

PET/CT scan with 18-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) showed marked metabolic activity, both nodal and extranodal, with intense pituitary uptake suggestive of tumour invasion (SUVmax 10.1) (Fig. 1), as well as a large sinonasal hypermetabolic mass and intense activity in the left L3, bilateral L5 and right S1 nerve roots (SUVmax 3.1), consistent with the patient’s symptoms of low-back pain. These results, in conjunction with those of the skin biopsy and LP, confirmed the diagnosis of stage IV ENKL-NT with skin and central nervous system involvement.

The patient suddenly developed severe dysphagia, which required treatment with high-dose intravenous dexamethasone (8 mg/8 h) and total parenteral nutrition (TPN). Chemotherapy was started and several LP were performed to assess the treatment response, with a decrease in NK cell infiltration from 74.4% to 5.1% after 10 days, and progressive improvement in the patient’s general condition. The EBV DNA result was positive, with 324,000 copies/ml. The patient required close follow-up by Endocrinology to adjust the desmopressin dose6 due to the high doses of corticosteroids received and the changes in fluid intake.

CDI is a complex disease often requiring extensive aetiological study. Although there have been several reported cases of lymphomas and other diseases with pituitary involvement,7,8 the first and only case of ENKL-NT with the initial manifestation secondary to invasion of the pituitary gland was described in 2007.9 In this case we ruled out underlying histiocytosis, autoimmune granulomatous diseases, a CNS germ cell tumour and various infections. The role of glucocorticoid therapy should be highlighted as, because cortisol is necessary for normal excretion of water, it can unmask incipient CDI.10 In this type of case, therefore, the participation of a multidisciplinary team is essential to guide the diagnostic process, with the aim of providing effective targeted treatment.