Morbid obesity is a disease with multiple comorbidities and considerably limits the quality of life and life expectancy. Bariatric surgery is an effective therapeutic alternative in these patients; it acts on the decrease and / or absorption of nutrients, achieving a significant weight loss which is maintained over time.

The objective of the study is to determine the long-term results, in terms of efficacy, regarding weight loss, the resolution of comorbidities and improvement in the quality of life of our patients.

Material and methodsThis was a retrospective study that comprised all patients consecutively undergoing laparoscopic bariatric surgery at our center over a 10 year period. In all patients, the anthropometric and clinical data were collected prior to surgery and in subsequent protocolized visits after surgery. At the end of the follow-up, a BAROS questionnaire was used that recorded weight loss, the resolution of comorbidities, complications and the quality of life test completed by the patients.

Results353 patients (303 GBPRY and 50 GV), 105 men and 248 women, with a mean age of 42.14 ± 10.16 years, BMI 48.63 kg / m2 and 68.5% had some comorbidity. The mean follow-up was 5.7 ± 2.6 years for 96.7% of the total number operated on.

At the end of the follow-up the %EWL was 59.00 ± 19.50, %EBMIL 68.15 ± 22.94, the final BMI 32.65 ± 5.98 and 31.3% of the patients had %EWL ≤ 50. The resolution of comorbidities was as follows: 48.7% hypertension, 70.3% Type 2 Diabetes, 82.6% DLP and 71.6% SAHS. The result of the quality of life test was 1.51 ± 0.93, with 67.2% of patients reporting good or very good quality, with the highest score being for self-esteem, followed by physical condition, work and social activity, and the lowest being for sexual quality of life in that only 40.3% reported an improvement. The BAROS score was 4.35 ± 2.06 with 84.7% of the patients in the good to excellent range, while 91.2% of all patients would undergo surgery again.

ConclusionsBariatric surgery is an effective technique for reducing weight, resolving comorbidities and improving the quality of life of patients with morbid obesity, mainly in its physical aspect. In our series, the percentage of follow-up and average time was within the range of established quality standards.

La obesidad mórbida es una enfermedad con múltiples comorbilidades y limita de forma considerable la calidad y esperanza de vida. La cirugía bariátrica es una alternativa terapéutica eficaz en estos pacientes; actúa sobre la disminución o absorción de nutrientes, consiguiendo una pérdida ponderal significativa y mantenida en el tiempo.

El objetivo del estudio es determinar los resultados a largo plazo en cuanto a eficacia en pérdida de peso, resolución de comorbilidades y mejoría de calidad de vida de nuestros pacientes.

Material y métodosEstudio retrospectivo que incluye a todos los pacientes intervenidos consecutivamente de cirugía bariátrica laparoscópica en nuestro centro durante 10 años. En todos los pacientes se recogieron los datos clínicos y antropométricos previos a la cirugía y en sucesivas visitas protocolizadas después de la cirugía. Al final del seguimiento, se utilizó cuestionario BAROS que registra pérdida ponderal, resolución de comorbilidades, complicaciones y el test de calidad de vida rellenado por los pacientes.

ResultadosTrescientos cincuenta y tres pacientes (303 BPGYR y 50 GV), 105 hombres y 248 mujeres, con edad media de 42,14 ± 10,16 años, IMC 48,63 kg/m2 y el 68,5% tenía alguna comorbilidad. El seguimiento medio fue de 5,7 ± 2,6 años al 96,7% del total de intervenidos.

Al final del seguimiento el PSP fue 59,00 ± 19,50, PEIMCP 68,15 ± 22,94, IMC final 32,65 ± 5,98 y un 31,3% de los pacientes con PSP ≤ 50. Resolución de comorbilidades: 48,7% hipertensión arterial, 70,3% DM2, 82,6% dislipidemia y 71,6% síndrome de apnea-hipopnea del sueño. El resultado del test de calidad de vida fue 1,51 ± 0,93, con un 67,2% de pacientes con calidad buena o muy buena, con la puntuación más alta en autoestima, seguido de actividad física, laboral y social, y la última la sexual en la que solo el 40,3% mejoran. El score BAROS fue de 4,35 ± 2,06 con el 84,7% de pacientes en rango de bueno a excelente y un 91,2% del total de los pacientes volvería a intervenirse.

ConclusionesLa cirugía bariátrica es una técnica eficaz para disminuir peso, resolver comorbilidades y mejorar la calidad de vida de los pacientes con obesidad mórbida, principalmente en el aspecto físico. En nuestra serie, el porcentaje de seguimiento y tiempo medio se sitúa dentro del rango de los estándares de calidad establecidos.

Obesity is a chronic disease with many causes which is on the increase and is putting an enormous financial strain on health spending here in Spain.1 From 1993 to 2006, there was a 200% increase in morbid obesity, from 1.8 to 6.1 per 1,000 population, with an annual relative increase of 4% in males and 12% in females.2

Compared to subjects with normal weight, morbid obesity increases the mortality rate in males by 52% and in females by 62%. It is also the second leading preventable cause of death after smoking.3

It has been found that for each increase in body mass index (BMI) of 5 kg/m2 there is a significant increase in mortality rate for type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM2) (HR 2.16), chronic kidney disease (HR 1.59), coronary heart disease (HR 1.39), stroke (HR 1.39), respiratory disease (HR 1.20) and cancer (HR 1.10).4

Bariatric surgery is currently the most effective strategy for achieving significant and sustainable weight loss, resolving comorbidities and reducing mortality in the long term.

To assess the outcomes of bariatric surgery, a specific questionnaire was validated for this type of patient, known as the BAROS score (Bariatric Analysis and Reporting Outcome System), which records the progression of comorbidities, weight loss and medical and surgical complications, as well as the patient's quality of life, using the incorporated Moorehead-Ardelt test.5,6

The aim of our study was to assess the outcomes in patients operated on in our hospital with a mean follow-up of almost six years and to compare them with those published by other groups, as well as to look for possible areas for improvement in the future.

Material and methodsThe study was a retrospective observational single-centre study which included all patients who underwent consecutive laparoscopic bariatric surgery, simplified Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) using the Lonroth and Ramos technique, or vertical sleeve gastrectomy with a 30-32 Fr bougie (VSG), from January 2005 to December 2014 in our hospital (coinciding with the implementation of the laparoscopic technique, as it had previously been performed by open surgery).

All patients were included in a database from the first visit and a pre-operative assessment was carried out following protocol, which included a medical history, physical examination, anthropometric, biochemical and hormone studies, along with additional tests to determine associated comorbidities, respiratory function tests, psychiatric and anaesthetic assessments, and informed consent.

Patient selection was carried out in accordance with the criteria laid out in the 2004 Consensus Document prepared by the Sociedad Española para el Estudio de la Obesidad (SEEDO) [Spanish Society for the Study of Obesity] and the Sociedad Española de Cirugía de la Obesidad (SECO) [Spanish Society of Obesity Surgery].3

After their surgery, patients were followed up at 1, 3, 6, 12, 18 and 24 months, and then annually. The patients were weighed and anthropometric variables were recorded at each visit, in addition to undergoing blood analysis and other tests necessary to assess their progress.

Major comorbidities were recorded: hypertension, DM2, dyslipidaemia (DLP), cardiovascular disease, sleep apnoea/hypopnoea syndrome (SAHS) and severe weight-bearing joint disease; and the following minor comorbidities: cholelithiasis, gastroesophageal reflux, fatty liver disease, menstrual disorders and infertility, stress urinary incontinence, varicose veins and benign intracranial hypertension, as recommended by SEEDO-SECO.3

The remission criteria for major comorbidities as established by the societies SEEN (Sociedad Española de Endocrinología y Nutrición) [Spanish Society of Endocrinology and Nutrition], SECO, SEEDO and SED (Sociedad Española de Diabetes) [Spanish Diabetes Society] are: in DM2, having HbA1c <6.5%, basal blood glucose <100 mg/dl and no drug treatment in at least one year of follow-up; in hypertension, achieving blood pressure <140/90 mmHg; and in DLP, triglycerides <150 mg/dl, LDL-C <160 mg/dl and HDL-C >50 mg/dl in females or HDL-C >40 mg/dl in males, with no drug treatment for these diseases. The diagnosis of obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome (OSAS) is determined by polysomnography study, if >5 events/h are observed, and for its remission in this study, ≤5 events/h were necessary.

The following recommended formulas were used to calculate weight loss:

- –

BMI = weight/height2.

- –

Percentage of excess weight loss: %EWL = ([initial weight - current weight)/(initial weight - ideal weight]) × 100.

- –

Percentage of excess BMI loss: %EBMIL = ([initial BMI - final BMI]/initial BMI - 25]) × 100.

- –

Percentage of total weight loss: %TWL = ([initial weight - current weight/initial weight]) × 100.

To assess the outcomes and quality of life, at the end of the follow-up we applied the BAROS questionnaire, validated for this type of patient which, in addition to weight loss, resolution of comorbidities and complications, includes the Moorehead-Ardelt quality-of-life test, which was filled in by the patients. The final outcome score is the sum of the items in all three categories and deductions for complications, as shown in Fig. 1. In the case of a major complication requiring reoperation, only one point is deducted.5,6

We compared the efficacy and quality-of-life scores obtained in our study with the quality criteria established by SECO7 and the American Society of Bariatric Surgery (ASBS) in order to rate the outcomes of the bariatric surgery.8,9

For the statistical analysis we used the SPSS database created for Windows Version 23.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, USA).

We carried out a descriptive study of the patients’ baseline variables. Categorical variables were described with frequencies and percentages, and continuous variables with mean and standard deviation.

We used the Student’s t-test to compare continuous variables, and Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables.

For all analyses, the level of statistical significance was set at 5%, 〈 = 0.05.

ResultsA total of 370 patients had surgery, of which 353 were included in the study; 12 patients (3.3%) (10 RYGB and 2 VSG) were lost to follow-up due to change of residence and five died, one as consequence of a surgical complication in the immediate postoperative period, and four from cirrhosis and malnutrition resulting from chronic alcoholism over many years.

Table 1 shows the clinical characteristics of the 353 patients in the study (303 RYGB and 50 VSG). They had a mean follow-up of 5.7 ± 2.6 (2.0-11.7) years, with 50.5% of them having follow-up for more than five years.

Patient clinical and demographic characteristics.

| Age (mean ± SD) | 42.1 ± 10.2 (19-68) |

| Initial BMI (mean ± SD) | 48.2 ± 6.3 (35.4-71.6) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 105 (29.7%) |

| Female | 248 (70.3%) |

| Type of surgery | |

| RYGB | 303 (85.8%) |

| VSG | 50 (14.2%) |

| Comorbidities | |

| Major | |

| No | 129 (36.5%) |

| 1 | 98 (27.8%) |

| 2 | 66 (18.7%) |

| 3 | 39 (11.0%) |

| 4 | 19 (5.4%) |

| 5 | 2 (0.6%) |

| Minor | |

| No | 247 (70.0%) |

| 1 | 95 (26.9%) |

| 2 | 10 (2.8%) |

| 3 | 1 (0.3%) |

| Previous treatment | |

| Dietary | 326 (92.4%) |

| Intragastric balloon | 17 (4.8%) |

| Gastric band | 4 (1.1%) |

| VBG | 6 (1.7%) |

VBG: vertical banded gastroplasty.

The total number of patients operated on by year was as follows: 2005 (9), 2006 (20), 2007 (17), 2008 (39), 2009 (19), 2010 (36), 2011 (41), 2012 (51), 2013 (59) and 2014 (62). The figures for VSG, introduced in 2010, were as follows: 2010 (4), 2011 (6), 2012 (8), 2013 (18) and 2014 (14).

Weight loss according to the three parameters detailed below was greater at 24 months after surgery than at the end of follow-up: BMI 30.56 ± 5.15 (18.4-50.7) vs 32.6 ± 6.0 (18.7-53.2); %EWL 67.1 ± 17.1 (5.9-118.3) vs 59.0 ± 19.5 (0.68-116.52); %EBMIL 77.5 ± 20.6 (6.6-147.2) vs 68.2 ± 23.0 (0.8-140.9) and %TWL 36.2 ± 9.2 (3.5-61.8) vs 31.9 ± 10.7 (0.3-58.7), in all cases p < 0.001.

The highest %EWL was found at 24 months and progressively decreased until 60 months, when there was a certain stabilisation. %EWL according to month of follow-up was: at month 6 (50.5%), 12 (61.1%), 18 (66.2%), 24 (67.1%), 36 (64.3%), 48 (59.9%), 60 (58.1%), 72 (56.3%), 84 (56%), 96 (54.1%), 108 (55.6%) and 120 (53.3%) (as shown in the box graph in Fig. 2).

At the end of follow-up, 68.7% of the patients had adequate weight loss (%EWL > 50%). Failures accounted for 31.3%, with 12.2% of the patients never managing to lose >50% of their excess weight. The percentage of patients with adequate weight outcomes according to month of follow-up was as follows: at month 12 (75.8%), 18 (84.7%), 24 (84.8%), 36 (79.8%), 48 (68.8%), 60 (61.9%), 72 (61%), 84 (58.2%), 96 (58.8%), 108 (61.8%) and 120 (47.6%).

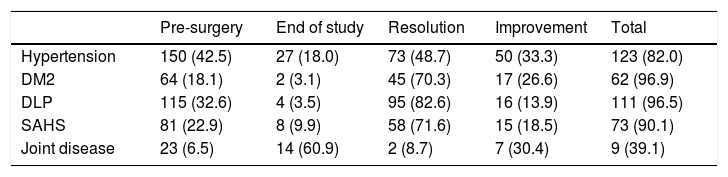

Before surgery 68.5% of the patients had some type of comorbidity, 63.5% at least one major and 30% at least one minor (Table 1). Table 2 shows the figures for patients with major comorbidities before and at the end of follow-up; the rates of remission or improvement were 82% for hypertension, 96.9% for DM2, 96.5% for DLP, 90.1% for SAHS and 39.1% for joint disease.

Percentage of remission of major comorbidities after bariatric surgery.

| Pre-surgery | End of study | Resolution | Improvement | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hypertension | 150 (42.5) | 27 (18.0) | 73 (48.7) | 50 (33.3) | 123 (82.0) |

| DM2 | 64 (18.1) | 2 (3.1) | 45 (70.3) | 17 (26.6) | 62 (96.9) |

| DLP | 115 (32.6) | 4 (3.5) | 95 (82.6) | 16 (13.9) | 111 (96.5) |

| SAHS | 81 (22.9) | 8 (9.9) | 58 (71.6) | 15 (18.5) | 73 (90.1) |

| Joint disease | 23 (6.5) | 14 (60.9) | 2 (8.7) | 7 (30.4) | 9 (39.1) |

Number of patients (%).

Right up to the end of the study, 34% of the patients had at least one complication: 19.4% had major complications (14.4% surgical and 5% medical); and 21.5% had minor complications (13.6% surgical and 7.9% medical).

The final score in the Moorehead-Ardelt quality-of-life test was 1.51 ± 0.93 (-3 to +3) and 67.2% of the patients rated it as good or very good (Fig. 3). No significant differences were found in the quality-of-life score between the patients who had complications and those who did not (1.54 ± 0.94 vs 1.46 ± 0.90, p = 0.496), but the score was better in those who had succeeded in losing weight (%EWL > 50%) at the end of the study (1.75 ± 0.78 vs 0.99 ± 0.99, p < 0.0001).

Self-esteem was the parameter that benefited most from bariatric surgery, followed by work activity, then social activity. The least satisfactory was sexual activity, with 50.6% of patients reporting no improvement and 9.1% saying that their sexual health had worsened (Table 3). The sexual quality score was higher in men than in women, although the difference was not significant (0.14 ± 0.21 vs 0.09 ± 0.23, p = 0.08). Only 3% of men reported their sexual quality to have worsened after surgery compared to 11.6% in women.

Results of the Moorehead-Ardelt Quality of Life Questionnaire.

| Much worse | Worse | Unchanged | Better | Much better | Mean ± SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-esteem | 2 (0.6) | 6 (1.8) | 13 (3.8) | 114 (33.5) | 205 (60.3) | 0.75 ± 0.36 (-1 to 1) |

| Physical activity | 2 (0.6) | 4 (1.2) | 74 (21.8) | 144 (42.4) | 116 (34.1) | 0.27 ± 0.20 (-0.5 to 0.5) |

| Social activities | 6 (1.8) | 8 (2.4) | 148 (43.5) | 106 (31.2) | 72 (21.2) | 0.17 ± 0.22 (-0.5 to 0.5) |

| Work activity | 6 (1.8) | 7 (2.1) | 132 (38.8) | 96 (28.2) | 99 (29.1) | 0.20 ± 0.23 (-0.5 to 0.5) |

| Sexual activity | 10 (2.9) | 21 (6.2) | 172 (50.6) | 86 (25.3) | 51 (15.0) | 0.11 ± 0.23 (-0.5 to 0.5) |

Number of patients (%).

The mean BAROS score was 4.35 ± 2.06 (-4 to +6) or (-5 to +9), depending on whether or not they had comorbidities, with 84.7% of patients reporting good to excellent quality (Fig. 3). For the questions on whether or not the bariatric surgery had fully met their expectations, 74.1% answered yes, and 91.2% of the patients said they would undergo it again.

Comparing the results of the study according to the type of surgery performed, as there were no significant differences in either weight loss, remission of comorbidities or quality of life, the results are shown globally.

DiscussionIn patients with morbid obesity, conservative treatment is not usually effective, and bariatric surgery is often necessary to reduce comorbidities and increase long-term life expectancy.

To evaluate the efficacy of the outcomes of bariatric surgery, weight loss and resolution of comorbidities are not the only important factors. We also have to assess the complications derived from the surgery and the patient’s perception of the improvement in their quality of life. The BAROS questionnaire, which we used in our patients, was specifically validated for this purpose and is widely used in assessing the outcomes of bariatric surgery.5

The results of the two techniques are presented jointly because we found no differences in terms of weight loss, remission of comorbidities or quality of life. We believe that this finding can be explained by a series of biases which prevent us from detecting the bypass technique’s superiority over VSG, such as: the small number of patients who underwent VSG (50 versus 303); the fact that VSG was not performed until 2010; and that 64% of patients with VSG had follow-up of two to three years, the period in which the best results are observed in terms of weight loss and remission of comorbidities.

Even so, we consider this study to be a faithful reflection of the outcomes in patients undergoing bariatric surgery at our hospital, as it includes 97.7% of the total, over 50% of whom have had follow-up of more than five years.

Loss to follow-up is a limiting factor in the evaluation of outcomes, so according to the International Bariatric Surgery Registry and the Standards Committee, follow-up should be available for at least 60% of patients for at least five years.9 It is well known that excellent results two years after the intervention can turn into outright failures, as weight gain and the recurrence of comorbidities and complications are common.10 Moreover, many patients with suboptimal results due to lack of adherence to dietary therapy stop attending consultations and are lost to follow-up, without being counted as failures in a significant number of studies.

In a study which included 114 patients who underwent bariatric surgery, Keren et al. found a clear worsening of outcomes at 60 months compared to those detected at 30 months, the %EWL decreasing from 76.8% to 45.3%, the BAROS score from 7.15 ± 0.8 to 4.32 ± 0.9 and the percentage of successful weight loss from 70.17% to 28.07%.11

There were similar findings in another study which compared the outcomes at one year and five years, where patient reporting of the "very good/excellent" BAROS scores fell from 81.8% to 60%, and of "good/very good" in the Moorehead-Ardelt test from 88.6% to 53.3%.12

Despite this, few authors report long-term bariatric surgery outcomes and the percentage of patients followed up is insufficient in many of the published studies. In a systematic review carried out by Puzziferri et al., which included 7,371 studies, only 16% had follow-up of more than five years, and of those, only 0.4% followed up at least 80% of the patients operated on.13

The 2004 SEEDO-SECO Consensus, based on the publications of Reinhold and MacLean, categorises the weight loss results as: excellent if BMI < 30 kg/m2 and %EWL > 75%, good if BMI 30-35 kg/m2 and %EWL 50-75%, and failure if BMI > 35 kg/m2 and %EWL < 50%.3

With this in mind, the results we obtained for weight loss according to the quality standards in our series are within the range classified as “good” if we take %EWL 50-65% with BMI 30-35 (59.0 ± 19.50) and as “excellent” if we take %EBMIL > 65% (68.15 ± 22.94) as reference. This is comparable to the figures published by other authors. Higa et al. report a %EWL at 10 years after RYGB of 57%, having followed up 26% of the patients until the end,14 and the meta-analysis by Buchwald et al. found a mean %EWL of 61.2%, with 70.1% of patients having had Scopinaro-type biliopancreatic diversion (BPD).15

As is to be expected, %EWL is higher in studies reporting results in the short-term: 74.6% from 12-24 months in one study;16 67% at 12 months in another study with few patients followed up;17 and 73.2% at 24 months in 45 BPD and 25 RYGB patients.18

In terms of comorbidities resolved, the rates for the patients in our study far exceeded those established by quality criteria, which are at least 70% for hypertension, DM2 and DLP, and 25% for SAHS at two years, except for hypertension, where we achieved a 48.7% cure rate and an improvement rate of 33.3%. If we had assessed this at two years after surgery when %EWL and resolution of comorbidities are at a maximum, the cure rate might well have exceeded 70%.

Nevertheless, similar results have been published in another study with follow-up similar to ours, with an improvement/cure rate for hypertension of 87%.14

In the SOS study, it was observed that in 13.2% of patients cured of hypertension their high blood pressure returned during the first years of follow-up.19

The results obtained in the quality-of-life questionnaire were optimal and 67.2% of the patients had a score in the good or very good range. The aspect that benefited most from weight loss after surgery was self-esteem, followed by physical and work activity, then social activity and, lastly, sexual activity; a finding common to other studies.

Sexual quality of life is the aspect with least improvement, and many series report that around 50% of patients do not experience any improvement and in 10% it gets worse.17,20–22 This was corroborated in one study, with 12% of patients experiencing a worsening of their sexual quality of life after surgery and 10% suffering rejection from their partner.23

Weight loss after bariatric surgery has been found to improve fertility in females and males, both in women with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), due to an increase in ovulatory cycles and pregnancy rate, and in men due to improvement in hypogonadism and semen quality.3 However, this finding is obviously not related to sexual quality of life. In our series, women frequently reported a decrease in libido, which may be explained by the drastic body changes which occur with weight loss, distorting their body image, as well as by the decrease in testosterone, which tends to be high in obese women with PCOS. In obese men, the opposite occurs when they lose weight and the testosterone available tends to increase, which would explain why only 3% of men reported a deterioration in their sexual quality of life after surgery compared to the 11.6% reported in women.

The good BAROS scores in our series are surprising (4.35 ± 2.06 [good/very good]), with 84.7% of our patients in the good to excellent range, despite a third of them failing in weight loss, mostly due to putting on weight again, and another third having had at least one complication from the surgery over the course of their recovery. On top of that, we have to add the negative impact on outcomes of the learning curve for the laparoscopic technique, with 28% having surgical complications, 14.4% of them major. Nevertheless, our results are even better than those obtained in another study with comparable characteristics to ours in terms of complication rate (35%) and weight loss failures (33.2%), where their BAROS score was 3.9 ± 2.6, with 68% in the good to excellent range.14

In a retrospective study of 77 patients with RYGB, Himpens et al. obtained a mean BAROS score at nine years of 2.0 ± 1.96, classified as fair and, surprisingly, 76% would undergo surgery again.24 Another study by the same author assessed the results at six years after VSG, obtaining a mean BAROS score of 5.0 ± 2.7 (good/very good), despite having a 23% incidence of reflux among their patients.25

One limitation of the quality-of-life questionnaire is that the result is influenced by patient subjectivity, which suggests that weight loss lower than that considered optimal may be enough to improve some comorbidities and the quality of life of our patients.

In addition, in this type of patient, weight loss is decisive when assessing outcomes, well ahead of any complications resulting from the surgery.

Finally, there is no doubt that weight loss improves physical appearance, self-esteem and mobility. However, there are other factors relating to the mental dimension which this score cannot measure and which do not benefit so much from bariatric surgery and may, in fact, even get worse.1,26,27

We therefore have to be aware that our work goes beyond improving the physical dimension and that we also need to focus on the psychological aspects for achieving our goals. This is particularly important considering that in a high percentage of patients, their obesity is the result of emotional imbalances which cannot be put right with the scalpel.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Junquera Bañares S, Ramírez Real L, Camuñas Segovia J, Martín García-Almenta M, Llanos Egüez K, Álvarez Hernández J. Evaluación de la calidad de vida, pérdida de peso y evolución de comorbilidades a los 6 años de la cirugía bariátrica. Endocrinol Diabetes Nutr. 2021;68:501–508.