To evaluate the indication and the resources for the screening/diagnosis of primary aldosteronism (PA) in Endocrinology units in Spain.

Material and methodsAn anonymous 2-phase (2020/2021) online survey was conducted by the AdrenoSEEN group among SEEN members with data about screening, confirmation tests, availability of catheterisation and the treatment of PA.

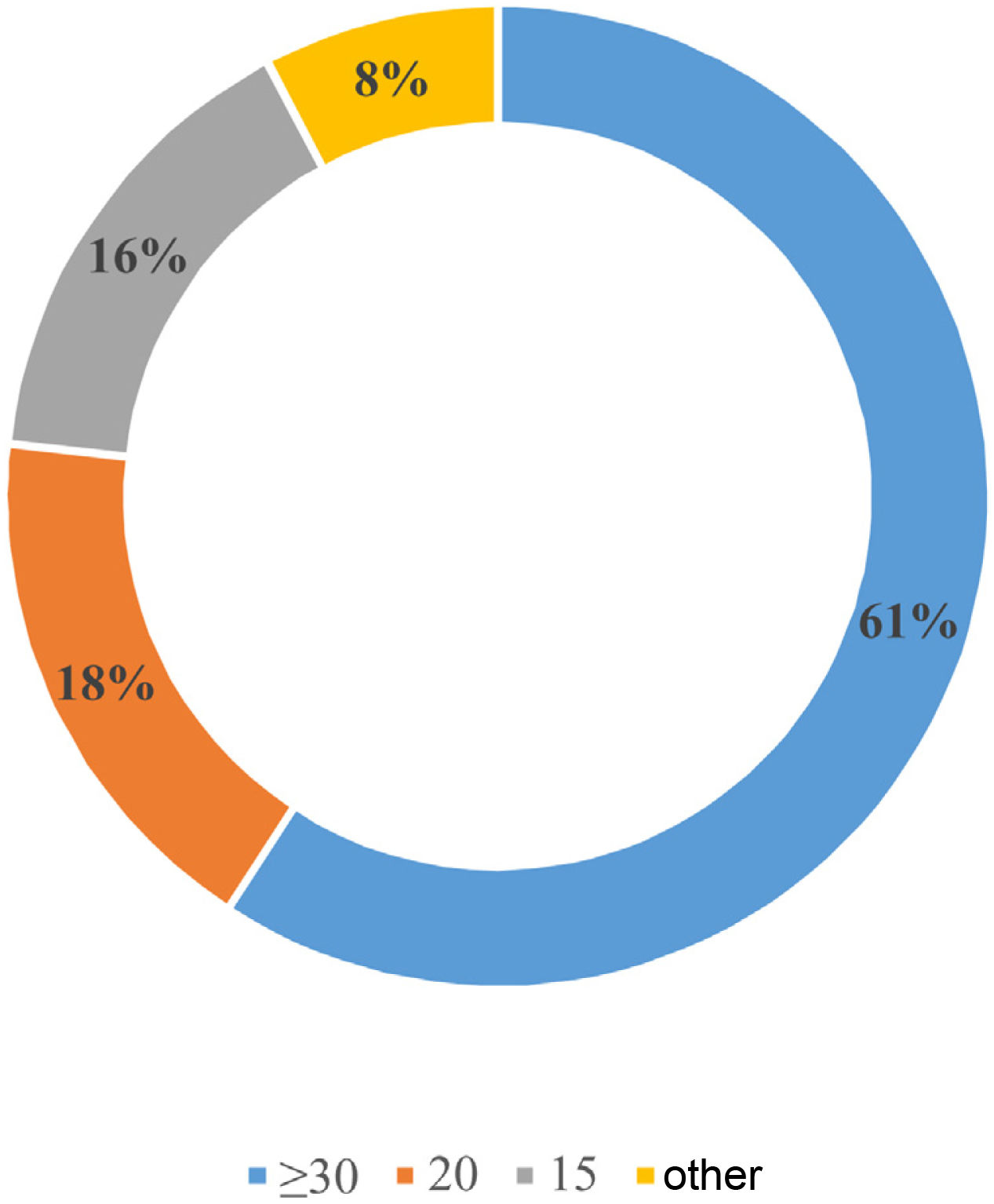

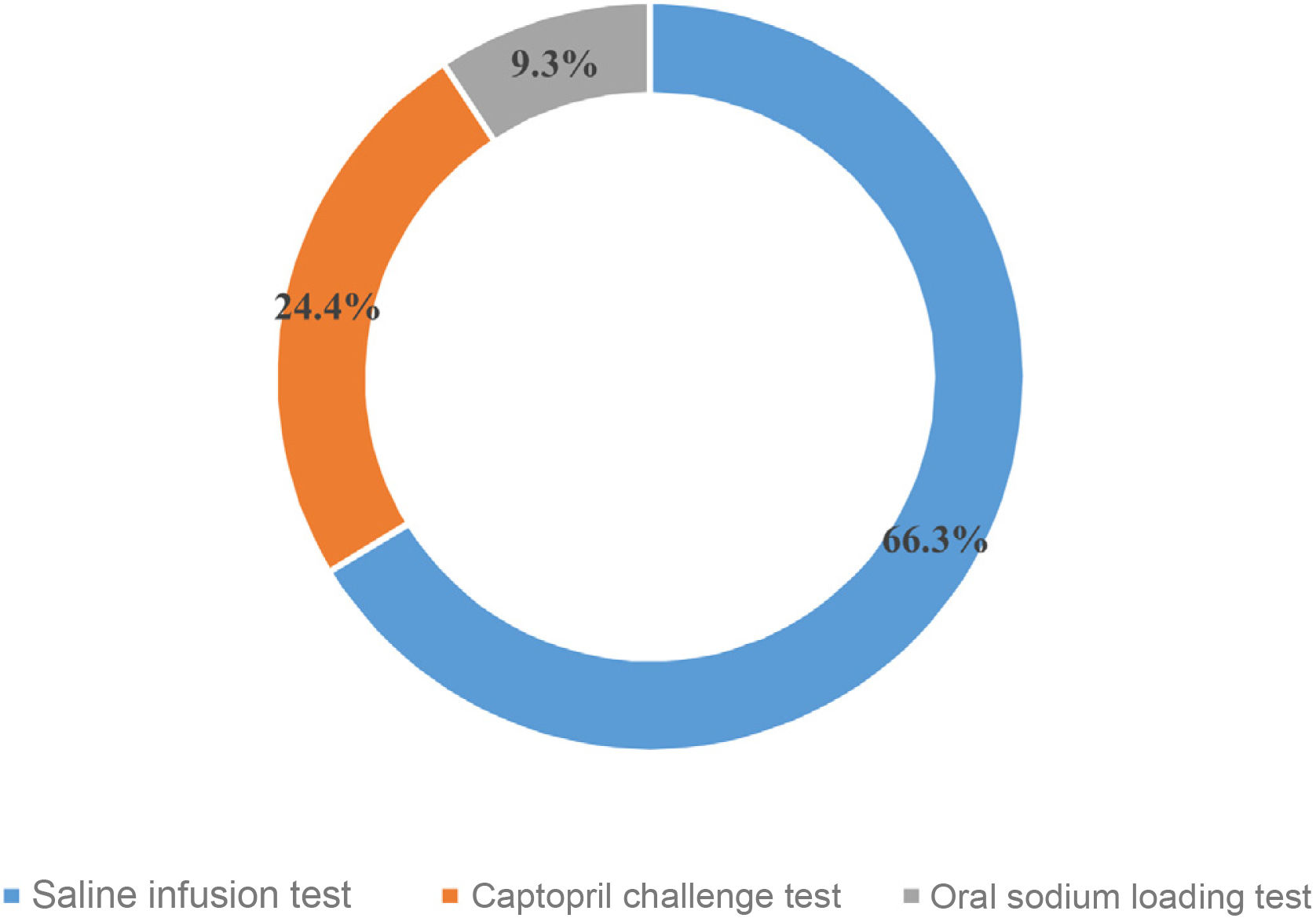

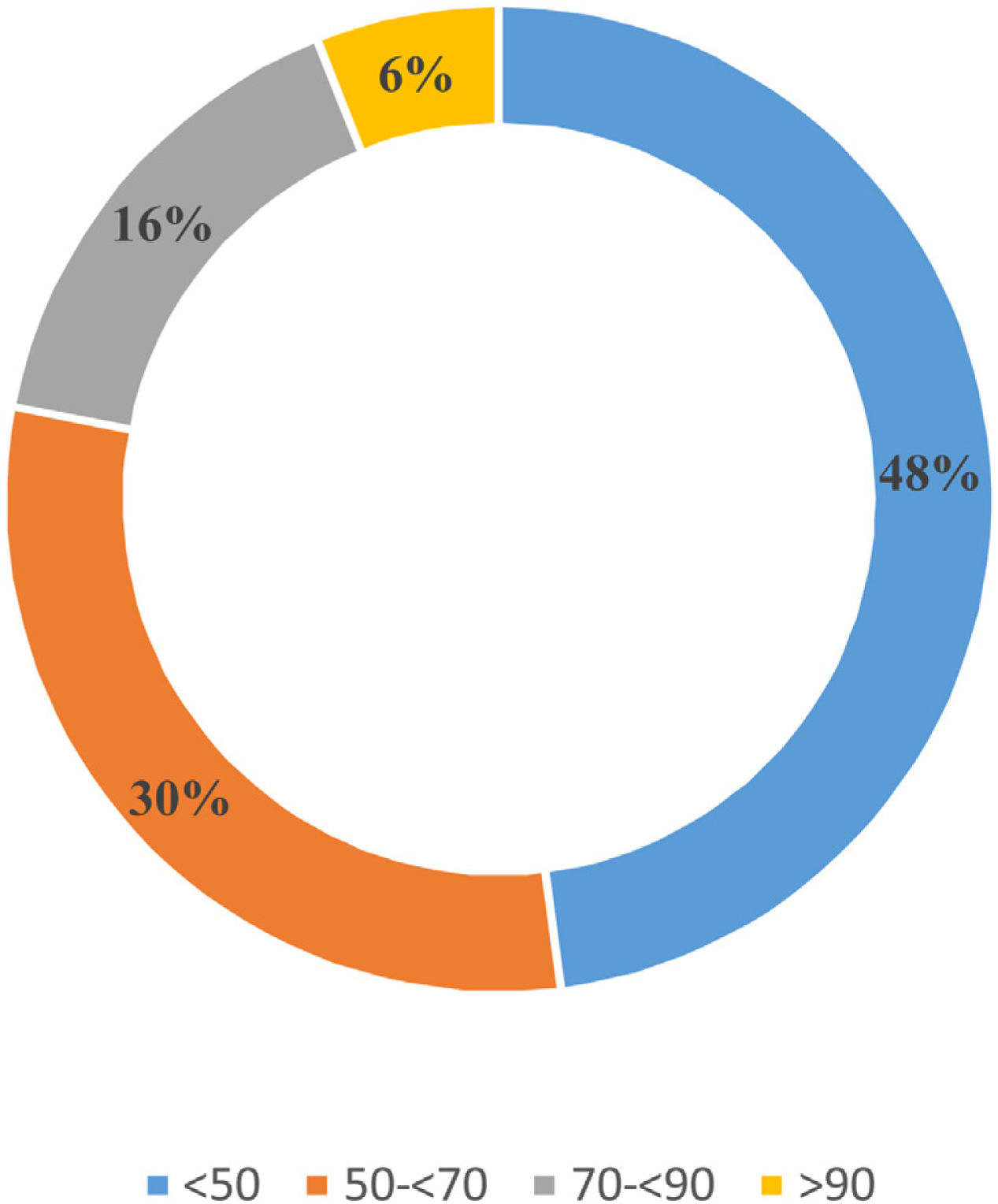

ResultsEighty-eight (88) specialists completed the survey. Plasma aldosterone concentration and plasma renin activity were available at all centres; urinary aldosterone was available in 55% of them. The most frequent indications for determining the aldosterone/renin ratio (ARR) were adrenal incidentaloma (82.6%), hypertension with hypokalaemia (82.6%), hypertension in patients <40 years (79.1%) and a family history of PA (77.9%). 61% and 18% of the respondents used an ARR cut-off value of PA of ≥30 and 20ng/dl per ng/mL/, respectively. The intravenous saline loading test was the most commonly used confirmatory test (66.3%), followed by the captopril challenge test (24.4%), with the 25mg dose used more than the 50mg dose (65% versus 35%). 67.4% of the participants confirmed the availability of adrenal vein catheterization (AVC). 41% of this subgroup perform it with a continuous infusion versus 30.5% with an ACTH (1–24) bolus, whereas 70.3% employ sequential adrenal vein catheterization. 48% of the participants reported an AVC success <50%. Total laparoscopic adrenalectomy was the treatment of choice (90.6%), performed by specialists in General and Digestive Surgery specialising in endocrinological pathology.

ConclusionPA screening and diagnostic tests are extensively available to Spanish endocrinologists. However, there is a major variability in their use and in the cut-off points of the diagnostic methods. The AVS procedure remains poorly standardised and is far from delivering optimal performance. Greater standardisation in the study and diagnosis of PA is called for.

Valorar la indicación y medios para cribado/diagnóstico del hiperaldosteronismo primario (HAP) en las unidades de endocrinología de España.

Materiales y métodosSe realizó por parte del grupo AdrenoSEEN, una encuesta electrónica anónima en 2 fases (2020/2021) a los miembros de la SEEN con datos sobre cribado, pruebas de confirmación, disponibilidad de cateterismo y tratamiento del HAP.

Resultados88 especialistas respondieron la encuesta. Todos los centros disponían de aldosterona plasmática y actividad de renina plasmática para diagnóstico; 55% aseguró disponer de aldosterona en orina. Las indicaciones más frecuentes para determinar el cociente aldosterona/renina (CAR) fueron el incidentaloma adrenal (82.6%), HTA con hipocalemia (82.6%), HTA en < 40 años (79.1%) y antecedentes familiares de HAP (77.9%). El 61% y 18 % de los encuestados utilizaban como punto de corte del CAR≥30 y 20ng/dl por ng/mL/h respectivamente. La sobrecarga salina intravenosa fue la prueba de confirmación más utilizada (66,3%), seguida del test de captopril (24,4%) utilizando más 25mg que 50mg (65 vs 35%). El 67,4% de los encuestados confirmó disponer del cateterismo de venas suprarrenales (CVS). De este subgrupo, un 41% lo realizan con infusión continua vs. 30,5% con bolo de 1–24 ACTH, y 70,3% con cateterización secuencial de venas adrenales. El 48% de los encuestados refirió un éxito del CVS<50%. La adrenalectomía laparoscópica total fue el tratamiento de elección (90,6%), realizada por especialistas en Cirugía general y Digestiva con dedicación a patología endocrinológica.

ConclusiónExiste una amplia disponibilidad de las pruebas de cribado y diagnóstico de HAP por parte de los endocrinólogos españoles. Sin embargo, destaca la variabilidad en la utilización y las discrepancias en los puntos de corte de los métodos diagnósticos. El procedimiento del CVS sigue estando poco estandarizado y lejos de un óptimo rendimiento. Se necesita una mayor uniformidad en el estudio y diagnóstico del HAP.

Primary hyperaldosteronism (PH) is characterised by inappropriate secretion of aldosterone for the blood volume, relatively autonomous and independent production of aldosterone by the renin-angiotensin system and a lack of suppression of aldosterone production in response to sodium overload.1 The main consequence of this abnormality is an increase in the effective circulating volume and, therefore, arterial hypertension (HTN). The effect of this excess circulating aldosterone on the mineralocorticoid receptors produces ionic and acid-base balance abnormalities, such as hypokalaemia and metabolic alkalosis. In addition, mineralocorticoid overactivation is associated with increased cardiovascular risk, leading to PH patients having greater morbidity and mortality compared to subjects with a similar degree of HTN.2,3

PH was traditionally considered a rare cause of HTN.4 However, with the new hormone testing methods, it has been observed that the prevalence of PH in patients with HTN exceeds 10%.1,5 Yet despite improvements in diagnosis, it is an under-diagnosed condition.4,6 The low incidence of PH in our consultations could be explained by several factors. These include: a lack of awareness of the disease in both primary and specialised care; screening focused on the severe phenotypes of the disease (hypokalaemia, resistant HTN), ignoring the broad clinical spectrum of the condition; and a complex diagnostic algorithm, coupled with the difficulties involved in changing antihypertensive medication in order to perform a good screening or confirmatory test.7 Similarly, patient examination may not yield a definitive result if there are limitations in the availability or success rate of adrenal vein sampling (AVS).8

To date, there have been no Spanish studies on diagnosis of, or adherence to the clinical guidelines for PH. As such, the objective of this study was to evaluate the indication and means available for screening for and diagnosing PH among Endocrinology and Nutrition specialists in Spain.

MethodsThe Adrenal Disease Group (AdrenoSEEN) of the Sociedad Española de Endocrinología y Nutrición [Spanish Society of Endocrinology and Nutrition] (SEEN) drafted a questionnaire with the aim of exploring: a) the availability of, and access to procedures used for screening and confirmation of the diagnosis of PH (13 questions); b) diagnostic methodology (19 questions); c) treatment (10 questions), and d) HTN units (4 questions) (Appendix A Annex 1). The survey was then evaluated and approved by the SEEN Board of Directors. Finally, the survey was sent out over two periods (from 5 October to 10 October 2020 and from 2 March to 1 April 2021 in order to increase the number of respondents) to all SEEN members by e-mail (n=1950). The survey was also disseminated through the SEEN website (www.seen.es) and professional Twitter account (@sociedadSEEN). The survey data were collected anonymously, allowing members of the same Endocrinology and Nutrition Unit to participate. Respondents who answered "yes" to the question about the availability of AVS at their hospital had to specify their workplace. In addition, as to the AVS success rate (defined as the percentage of AVS that enabled the subtype of PH to be established), the respondent was asked whether this was a subjective assessment or, alternatively, based on the centre’s records.

A descriptive analysis of the results was conducted, expressing qualitative variables in absolute numbers and percentages.

ResultsA total of 88 respondents (4.51%) answered the questionnaire, 41 in the first phase and 47 in the second phase.

PH screeningOverall, 91% (n=80) and 100% (n=88) of respondents indicated that plasma renin and aldosterone activity was available for PH screening and diagnosis, while only 56% (n=49) had 24-h urine aldosterone concentrations and 2% (n=2) of the respondents had direct plasma renin concentrations available. However, only 37.2% (n=33) of the respondents knew the type of laboratory technique used to measure hormone levels.

To optimise screening and confirmatory testing, 95.3% (n=84) withdrew mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists, 76.5% (n=67) withdrew diuretics, 69.4% (n=61) withdrew angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) and 49.4% (n=43) suspended beta-blockers. A total of 2% of participants (n=2) did not consider withdrawing or changing antihypertensive medication, and 40% (n=35) assessed suspension according to the severity of HTN.

Screening for PH with assessment of the aldosterone-to-renin ratio (ARR) would be done in patients with adrenal incidentaloma by 82.6% of respondents (n=73); in patients with hypokalaemia-associated HTN by 82.6% (n=73); in patients with HTN diagnosed before the age of 40 by 79.1% (n=69.5); in patients with a family history of PH in 77.9% (n=68.5); and in patients with HTN treated with more than three drugs by 75.6% (n=66.5). Only 7% (n=6) and 2.3% (n=2) of participants consider screening for PH in patients with sleep apnoea-hypopnoea syndrome (SAHS) and atrial fibrillation, respectively. Fig. 1 shows the ARR cut-off points considered positive for PH screening by respondents.

Similarly, 80% (n=70) of the participants evaluated the aldosterone concentration together with the ARR, increasing the diagnostic suspicion when the values were ≥15ng/dl and ≥10ng/dl for 35 and 18 of the 70 respondents, respectively. The concentration of aldosterone used as a threshold for suspicion was not specified by the remaining 17 respondents.

Biochemical diagnosis of PHThe majority (93%, n=82) of respondents reported using the saline infusion test (SIT) and the captopril challenge test (82%, n=72) as confirmatory tests. The fludrocortisone suppression test and the oral sodium loading test (OSLT) were available for 45% (n=40) and 54% (n=48) of participants, respectively.

The confirmatory test considered the first choice for respondents is shown in Fig. 2. None of the respondents reported using the fludrocortisone suppression test. With regard to the captopril challenge test, 25mg (65% [n=57]) was administered more frequently than 50mg (35% [n=31]). In total, 58% (n=51) of respondents indicated that the confirmatory test was conducted with the patient in a supine position versus 42% (n=37) in a seated position.

The most commonly used plasma aldosterone cut-off point for the diagnosis of PH after the SIT was 10ng/dl (62%, n=54). Some 78.5% (n=69) of the respondents reported repeating the SIT with aldosterone values of 5−9ng/dl.

On the other hand, 36.5% (n=32) of respondents reported having a genetic test available to rule out type 1 familial PH. In total, 46.3% (n=15) of the subgroup of respondents who had this test available considered it in patients with a diagnosis of PH<20 years, while 40.7% (n=13) considered it in those with a diagnosis of PH>40 years. The remaining 13% (n=4) considered the genetic study in all patients.

Aetiological diagnosis of PHWith regard to AVS, 67.4% (n=59) of the participants confirmed having AVS available in their hospital, constituting 30 Spanish hospitals (Appendix A Annex 2). AVS is most often performed under stimulation with continuous infusion of 1–24 ACTH (Synacthen® [Sigma Tau Pharmaceutical Company] or Cosyntropin® [Amphastar Pharmaceuticals]) (41%, n=24), followed by a bolus of 1–24 ACTH (30.5%, n=18), while 16.4% (n=10) did not use 1–24 ACTH. The remaining 12.1% (n=7) of the participants did not know the AVS methodology used at their centre. In addition, 70.3% (n=41) of the subgroup with AVS availability reported that sequential sampling of the adrenal veins was performed in their institution versus 29.7% (n=18) with simultaneous sampling. Some 66.2% (n=36) of respondents reported ≤3 AVS per year, with the majority (67.6%, n=40) requiring admission to hospital and discontinuation of mineralocorticoid receptor blockers (94.1%, n=55). Fig. 3 shows the percentage of AVS that helped clarify the PH subtype reported by the respondents. This information was subjectively expressed by 63% (n=37) of participants with AVS, versus 37% (n=22) who had institutional records.

On the other hand, 32% (n=28), 6% (n=5), and 4% (n=4) of respondents reported that the percentage of PH with bilateral aetiology was between 10% and 29%, 30% and 50% and >50% of cases evaluated, respectively.

With regard to the study and follow-up of comorbidities, 47.7% (n=42) considered a cortisol cosecretion screening study only in the case of an adrenal nodule, 19.8% (n=17) screened for SAHS, and 39.5% (n=35) screened for hyperparathyroidism.

Surgical treatmentIn the case of surgical indication, total laparoscopic adrenalectomy was the treatment of choice (90.6%, n=80), preceded by pre-operative treatment with mineralocorticoid receptor blockers (56.5%, n=50), while 30.6% (n=27) considered adding them only in the event of HTN that was difficult to control. In total, 29.6% (n=26) indicated surgery based on abdominal CT findings. Some 65.1% (n=57) of respondents reported <10 adrenalectomies per year. Adrenalectomy was performed by general and gastrointestinal surgery specialists dedicated to endocrine disease in 56% (n=49.2) and by urology specialists in 23.8% (n=21).

On the other hand, 65.1% (n=57) of participants reported using several parameters for mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist titration, including blood pressure (BP), serum potassium and plasma renin. In total, 26.7% (n=23.4) reported that it was based solely on BP figures.

At postoperative follow-up, 80% (n=70) of participants denied having a postoperative surveillance protocol to assess aldosterone/renin levels. The first biochemical assessment of renal function and electrolytes is performed three days after surgery by 25.6% (n=22) of respondents and one week after surgery by 23.3% (n=21).

Regarding the duration of follow-up after surgery, 32.9% (n=29) followed up for one year, 23.2% (n=20) for five years and 43.9% (n=39) provided long-term follow-up (>5 years).

HTN unitsOverall, 35% (n=31) of endocrinologists reported having a specialist consultation on PH. However, 67.1% (n=59) mentioned the existence of HTN working groups/units in the hospital, but that are dependent on other clinical departments.

DiscussionThis study presents the results of the first national survey on the diagnostic and therapeutic approach to PH by Endocrinology and Nutrition specialists. The wide availability of screening and diagnostic tests for PH in Spanish centres is noteworthy.

There is a broad consensus among respondents on the screening and diagnostic tests to be performed, but not when it comes to defining the ARR cut-off points or aldosterone levels used for screening. The ARR cut-off point of choice for 61% of respondents to define screening indicative of PH was ≥30ng/dl per ng/ml/h. This is consistent with data from the survey conducted in Italian centres specialising in HTN showing that this cut-off point was used in 56% of centres.9 However, this cut-off point maximises specificity—and thus decreases false positives—but also reduces sensitivity, so that cases of potentially curable HTN may be lost to screening.

The results show close to 80% agreement on screening in patients with adrenal incidentalomas, HTN in young people or with hypokalaemia, HTN treated with three drugs, and in patients with a family history of PH, compared to only 7% and 2.3% screening in those patients with HTN and SAHS or atrial fibrillation, respectively, with screening for PH in these diseases being recommended by Societies of Endocrinology4,10 and Hypertension11,12. Previous studies have shown that atrial fibrillation is more common in patients with PH than in patients with essential HTN.3,13 On the other hand, PH is more frequently associated with obesity-related diseases such as SAHS14. However, there is still no consensus about whether PH is more prevalent in individuals with SAHS.15 These entities are associated with high cardiovascular morbidity16,17, whose coexistence with PH can act synergistically to increase cardiovascular risk and target organ damage. Accordingly, patients with such comorbidities may benefit from the identification and specific treatment of PH, whether surgical or, in the case of bilaterality, pharmacological treatment.

One of the factors affecting the interpretation of screening or confirmatory tests for PH is the patient's antihypertensive medication. The guidelines recommend that drugs with greater interference, such as mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists and diuretics, be discontinued for four weeks, and ARBs, ACE inhibitors, beta-blockers, and dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers for two weeks.10,12 However, a change of medication is considered a limiting factor for physicians when screening for PH, due to the consultation time it entails and the possible risk it may pose in patients with severe hypertension.18 In our survey, the vast majority follow these recommendations. However, 40% assess therapy suspension based on the severity of HTN. In these higher risk cases, continuation of treatment may be recommended, especially in patients in whom renin remains suppressed, as well as to only assess a complete pharmacological change in patients in whom renin is not suppressed and a high diagnostic suspicion persists.19 In addition, it is important to highlight the influence of many other non-pharmacological factors on the ARR, such as gender, time of extraction, sodium intake in the days prior to the test or body position at the time of extraction. Not all of these are standardised, but it is important to understand how they affect the result and be able to interpret them correctly.20

In light of the foregoing, because of the arbitrariness of the ARR cut-off points and the variability in the values, and because of the definition of the disease itself, a confirmatory test must always be carried out, except in very exceptional cases, to ensure that aldosterone is not suppressed after volume overload,10,12 or a test to suppress endogenous aldosterone production.11 The four confirmatory tests recommended by the Endocrine Society are the SIT, the captopril challenge test, the oral sodium loading test and the fludrocortisone suppression test.10 The test most commonly used by our respondents is the SIT, with no use of the fludrocortisone test, classically considered the gold standard, but with greater complexity, greater risk of complications and costs as it requires several days of hospital admission.21

The second most commonly used confirmatory test among respondents was the captopril challenge test, which is a simple and inexpensive test with no secondary risks to volume overload, but with no uniformity in either the dose to be used, the postural measurements or the time of extraction. This is attested to by our data, the majority of which use the 25-mg dose of captopril, in contrast with the Italian centres, in which 50mg is the dose of choice9 or the recommendation by the Japanese HTN guidelines22. The oral sodium loading test is used less frequently (9.3%), coinciding with the lower availability of urinary aldosterone concentration in some centres.

A meta-analysis has recently been published comparing these four tests23, which highlights the significant heterogeneity in diagnostic cut-off points. This is supported by our survey, in which 38% of the respondents considered a plasma aldosterone concentration cut-off point other than 10ng/dl in the SIT. This same article justifies the use of the captopril challenge test with yields similar to that of the SIT23 as long as there is a good sodium intake in the days prior, which is difficult to assess, unless urinary sodium excretion is quantified. The heterogeneity of the captopril challenge test is also analysed, with no justification found either for the time in which the extraction is performed (1h–1.5h–2h) or for the value used for diagnosis: ARR or plasma aldosterone concentration. In our study, slightly more than half of the respondents performed the confirmatory test with the patient seated versus in supine position. To date, no consensus has been reached on this and there is only evidence of higher aldosterone levels when sitting vs lying down and, therefore, a potential greater sensitivity of the test if it is performed with the patient seated.10,24

After confirming the diagnosis of PH, the next step will be to distinguish between bilateral or unilateral disease to identify those patients who are candidates for surgical treatment, with AVS playing an indisputable role in this step.25 Approximately two out of three endocrinologists reported having AVS at their centre to complete the localisation study. However, the low AVS success rate reported by respondents is concerning. One of the factors that could contribute to these results is the sequential sampling of adrenal blood in most centres (70.3%). Ideally, simultaneous bilateral sampling should be the method of choice to minimise time-related variability due to the pulsatile pattern of cortisol and aldosterone secretion, which can lead to hormone concentration gradients between the two sides.25–27 In fact, in the study by Rossitto et al., samples obtained by simultaneous bilateral AVS provided more accurate identification of lateralisation than those obtained sequentially. Furthermore, the chances of causing factitious lateralisation towards the last sampled side were greater with the sequential technique.26 However, this method may require greater technical expertise. In our results, the success rate was less than 50%, which is consistent with publications from other centres that routinely perform AVS, where the overall rate of catheterisation and adequate localisation was only 30.5%.28 The centralised conduct of AVS in a few reference centres29 can be explained by the fact that it is an operator-dependent procedure, the success of which depends on experience, and its complications decrease significantly if it is performed in centres that conduct a high number of procedures per year.30,31

Obviously, the low success rate of AVS reported in our study could contribute to the low number of annual adrenalectomies indicated (<10). As such, standardisation of the procedure and implementing prospective national registries that include adrenal vein sampling data in order to identify referral centres would be meaningful.

This survey also made it possible to identify unmet needs in this disease, such as: the limited screening for comorbidities like SAHS and hyperparathyroidism; the limited availability of genetic studies for familial forms of PH; the need to establish postoperative follow-up protocols with monitoring of aldosterone/renin, renal function and electrolytes; the low number of specialist consultations in this field; as well as the limited participation of Endocrinology and Nutrition specialists in HTN units. We believe that these results reflect the need to raise awareness of, and call attention to this common disease for all specialists who treat patients with HTN and to maximise the establishment of specific and multidisciplinary HTN units with the participation of Endocrinology, promoting the early diagnosis of PH and its comorbidities, in order to opt for the best surgical or medical treatment, and cardiac, vascular and renal risk control.

Our study is limited by the low number of participants and by being based on the experience of the participants. This could be explained by a response bias, whereby the professionals most closely linked to the study of PH responded. These circumstances make it difficult to gain a credible understanding of how PH is diagnosed and treated by Spanish Endocrinology and Nutrition specialists. Despite this, this study looked for the first time at the situation facing endocrinologists in terms of the diagnostic and therapeutic approach to PH in different Spanish centres.

In conclusion, Endocrinology and Nutrition specialists face no limitations for conducting adequate PH screening. However, the localisation study through AVS is still far from yielding optimal results. It is necessary for SEEN working groups to join forces to promote the screening of PH in Spain and to simplify the diagnostic approach to facilitate effective, targeted treatment.

FundingThis research has not received specific funding from public sector agencies, the commercial sector or non-profit organisations.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest related to this paper.